25 years in Sibera. In the late 1980s, I became convinced the Japanese stock and real estate markets were engulfed in one of the biggest speculative manias in world history. It was the first time I started using the B-word—as in "bubble"—in my conversations with clients. Some readers may remember that the most egregious example of that era’s insanity was the alleged valuation of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo being worth more than all the property in California. Now that’s a bubble!

As is almost always the case, the red giant that was Japan’s asset markets continued to expand, even as renowned investors like GMO’s Jeremy Grantham outlined the persuasive case on why a future disaster was coming. In fact, Mr. Grantham began to warn about Japan in 1986—a full four years before the planet’s star market became the ultimate black hole. By the time Japanese stocks and real estate began to crack in 1990, the alarm-sounders were thoroughly discredited and ignored (some things never change!).

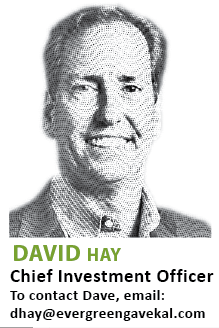

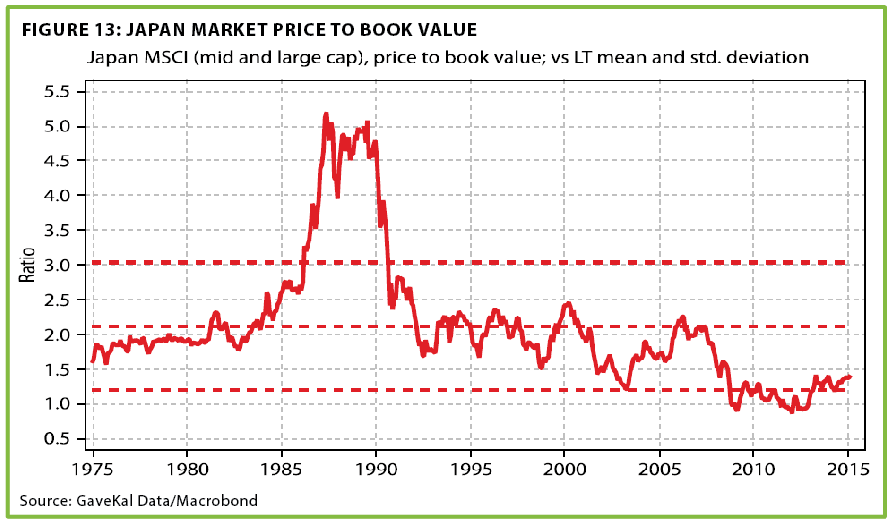

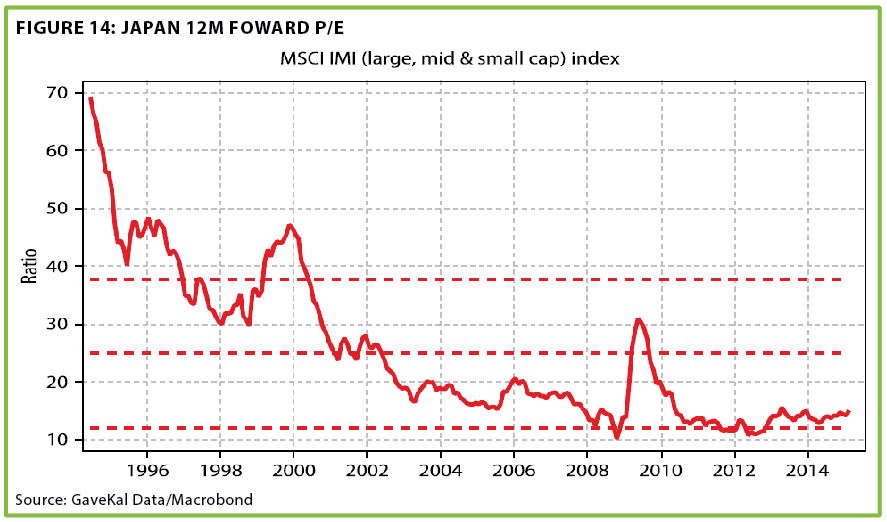

There’s not much doubt that the enormity of the bubble was the prime reason the Japanese market still trades at just half its 1990 value, despite more than doubling (at least in yen terms) over the last two and a half years.

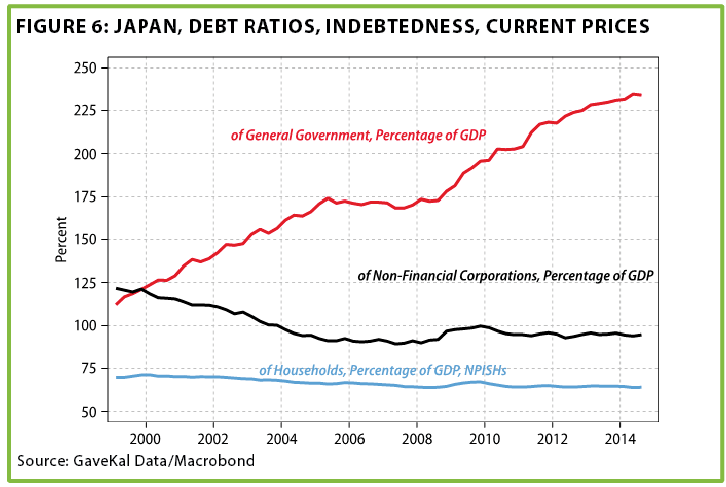

To put this in perspective, in the case of America’s infamous 1929 crash, and the subsequent Great Depression it helped create, the Dow had regained its pre-meltdown peak by 1954. The Japanese stock market’s last two and a half decades occurred despite (or, possibly, because of) a blitzkrieg of Keynesian "remedies" implemented by its policymakers since the bursting of its epic bubble. These included the world’s first zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) and a never-ending series of fiscal deficits that have left Japan with a gross government debt-to-GDP of 225%, more than double America’s nauseatingly high level.

Its sorry financial condition was a big reason why Evergreen almost totally avoided Japanese shares for many years, and also had a de facto short position in the yen for most clients. Starting a year or so ago, however, we began to believe its stocks might be poised to end their quarter-century residence in the investment equivalent of Siberia. As more time has gone by, we’ve come to believe that the rays of light in Japan’s market might truly represent daylight at the end of its long tunnel rather than an oncoming bullet train. Hence, this month’s full-length edition of EVA is devoted to that possibility.

But, before I get into the reasons why Japan might be the world’s comeback kid, let’s get the caveats out of the way.

How do you say "sausage factory" in Japanese? The old saying is that if you want to eat sausages its best not to watch them being made. The same is true with the process by which Japan is seeking to end its 25-year battle with bear markets in stocks and real estate as well as its constant struggle against deflation.

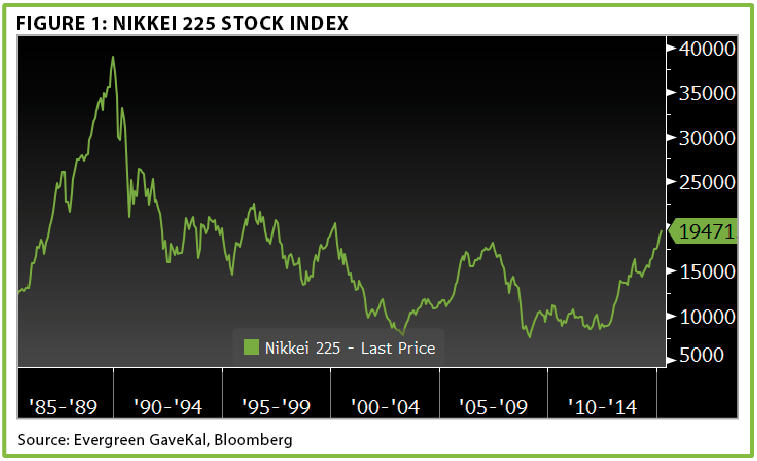

It’s no secret to EVA readers that I believe quantitative easings (QEs) are of questionable benefit for an economy, even though they have proven to be rocket fuel for financial markets (time will tell if there will be a costly pay-back for the latter effect). And Japan has resorted to the most aggressive—some might say desperate—QE effort in the world. As you can see below, the expansion of the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) balance sheet makes the Fed look downright timid.

Additionally, the BOJ has added another letter to the QE acronym. Their reflation program is officially known as QQE, or Quantitative and Qualitative Easing. The "Qualitative" part means that Japan’s central bank is using the money it has created to directly buy assets, like stocks, rather than merely relying on market participants to funnel the excess liquidity toward equities as the Fed has done. Thus, we’re talking QE on steroids.

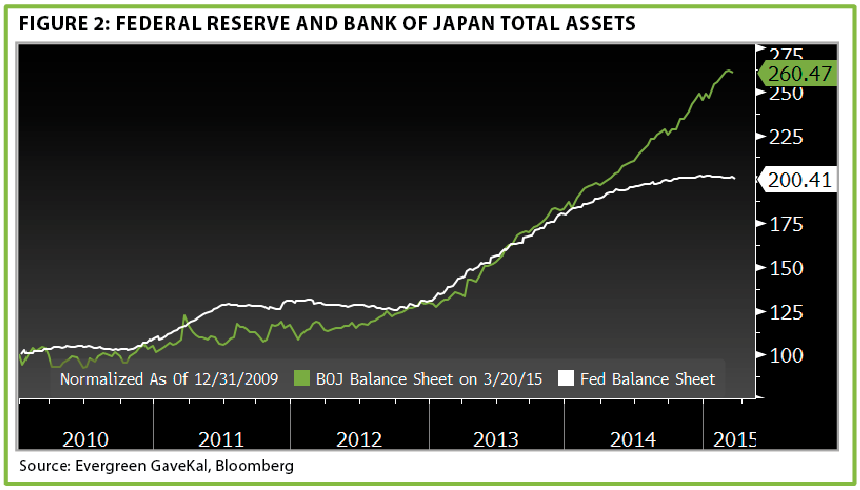

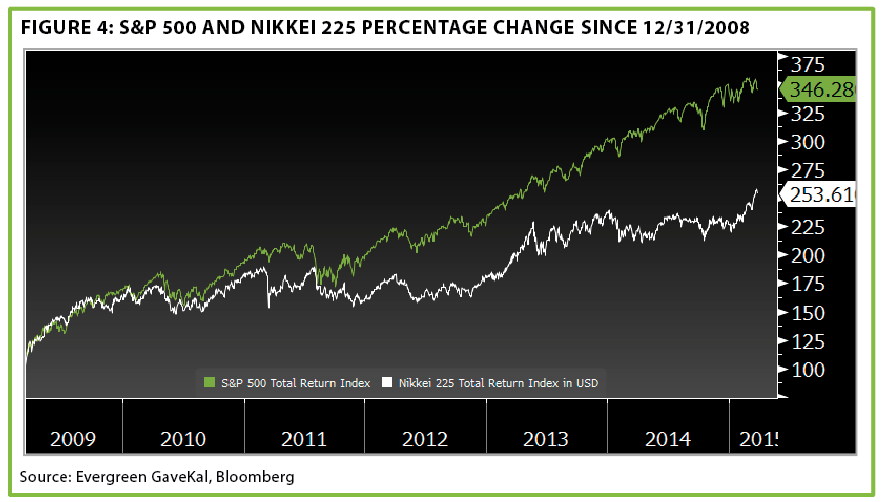

There’s little doubt this is why Japan’s stock index, the Nikkei 225, has been on a tear since QQE was unveiled in April of 2013. The catch for US investors, though, is that in dollar terms, the returns have been much more modest due to the 33% cliff dive by the yen since QQE was launched. Per figure three below, the Nikkei in dollars has trailed the S&P from the start of Japan’s extraordinary stimulus program. From the bottom of the financial crisis, the lag has been even more pronounced (figure four).

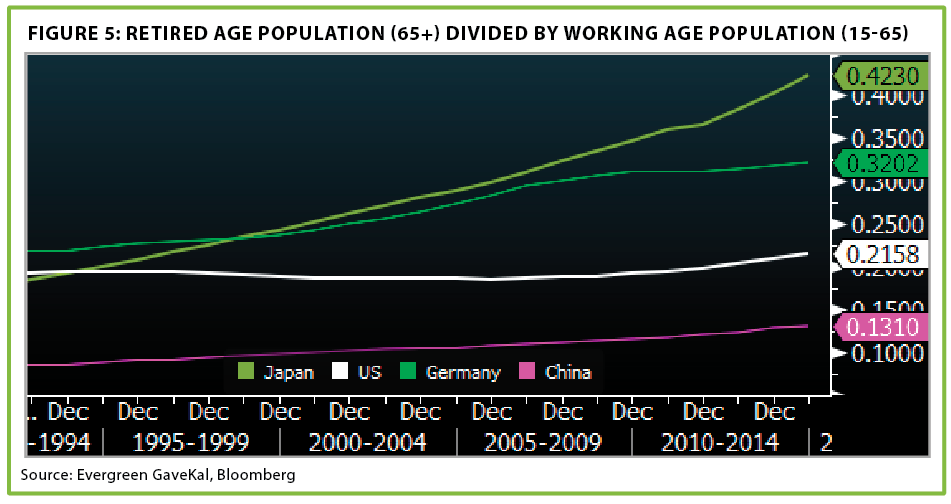

Beyond the negative of enormous government debt, there is Japan’s grim demographic situation. The country is rapidly aging as reflected in this factoid: Last year, more adult diapers were sold in Japan than infant diapers. That’s enough to make any bull on Japan feel more than a little incontinent! Even compared to other graying countries, Japan is uniquely geriatric.

Further, Japan’s legendary and once enviable savings rate is no more. In reality, Japanese savers have begun to consume some of their capital base, likely as a result of the inability to generate a livable return (US investors take note). For those who hold stocks, the monster rally of the last few years has relieved some of the pressure but equities are not nearly as widely held in Japan as they are in the US.

Finally, Japan’s legendary and once enviable savings rate is no more. In reality, Japanese savers have begun to consume some of their capital base, likely as a result of the inability to generate a livable return (US investors take note). For those who hold stocks, the monster rally of the last few years has relieved some of the pressure but equities are not nearly as widely held in Japan as they are in the US.

Okay, with those glaring weaknesses identified, let’s consider why they might not be fatal.

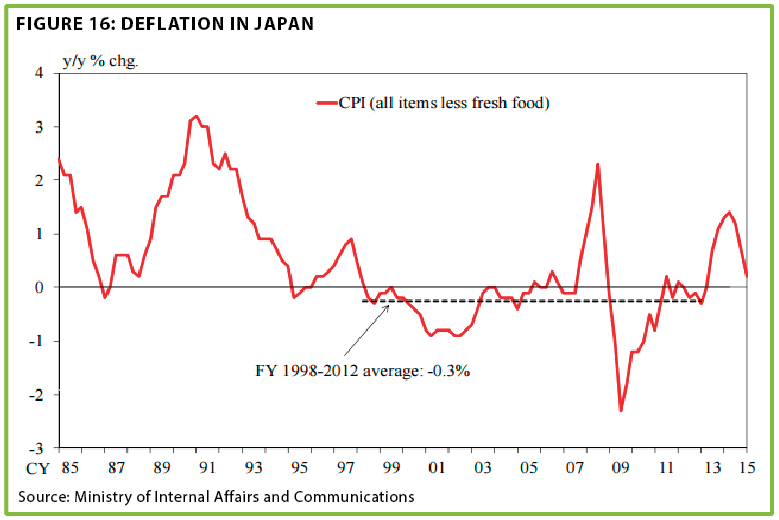

Examining both sides of the ledger. First, it’s been my concern that Japan may resort to actual physical currency printing, versus the usual central bank electronic reserve creation, as a last-ditch attempt to defeat deflation. As the brilliant William White has observed*, deflation often precedes hyperinflation.

*Mr. White was formerly the chief economist at the Bank for International Settlements, known as the central banker for central banks.

Wildly printing bank notes is what caused inflation in both Germany in the 1920s, and Zimbabwe in recent times, to go exponential. Yet, as my friend and newest team member Grant Williams has pointed out to me, even when Japan gave its citizens what essentially amounted to refund checks, most opted to simply stash them away. This is despite the fact they had an expiration date! In other words, this is a society that does not seem to respond to money raining down from helicopters.

Another reason Japan may avoid an inflationary nightmare is that it domestically owns nearly all of its debt. In other words, Japan is in hock to Japan with the older generations owning most of the IOUs. Another close friend and partner, Louis Gave, also based in Asia, believes Japan’s way out of its debt trap is something along the lines of an annuity. The government would guarantee an income for life to a retired Japanese investor who would in return surrender his or her bonds. At death there would no longer be a claim against the country’s finances. The other option would be a hefty inheritance tax so that the older generations would effectively pay down part of the national red ink. Either way, over time, debt would gradually be reduced or at least, hopefully, stabilized.

Additionally, Japan has immense overseas assets, not just the second largest cache of US treasuries, but also what is arguably the most impressive set of off-shore manufacturing facilities any country can boast (think of Toyota and Nissan plants dotting the US, Canada, and Mexico). On this basis, its overall debt to the size of both its domestic and international assets may not be nearly as alarming as the traditional debt-to-GDP metric.

Another oft–overlooked strength of Japan is the considerable liquidity of its private sector. Japanese businesses and consumers have spent most of the last two decades deleveraging. After all, in a deflationary environment, debt is very costly even at low interest rates. Consequently, the leveraging up of the government’s balance sheet has been the inverse of the private sector debt pay down (though the government has added more debt than the private sector has extinguished).

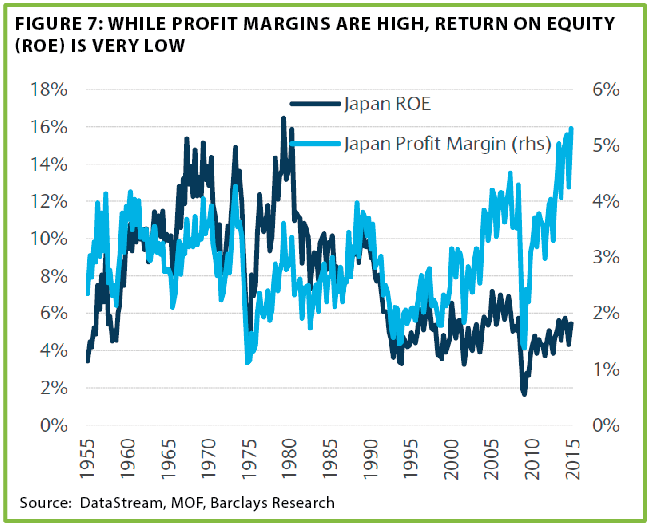

The corporate deleveraging that has occurred is reflected in the following charts showing how Japan’s profit margins have soared while return on equity has stayed depressed. (As debt is repaid, return on equity tends to be inhibited.)

However, the surge in profit margins is a pivotal development in Japan and is definitely a major piece of the bull story. This may be where the vaunted "third arrow" of its economic reform package may finally be whistling through the air.

Japan’s William Tell? In conjunction with the BOJ’s 2013 monetary tsunami, Japan’s charismatic Prime Minister Shinzo Abe unveiled his "three arrows" program to revive Japan. The first arrow was monetary (QQE), the second was fiscal (meaning running even larger deficits), and the third was to be reforms of the ossified corporate and regulatory sectors. This ambitious agenda was soon dubbed "Abenomics" in the PM’s honor (or dishonor if it doesn’t work).

For a time, it looked like the third arrow was stuck in the quiver. Lately, though, there has been real progress including, according to Morgan Stanley chief strategist Michael Wilson, in both agricultural and health care. Also, as he notes, the fact that Japan has joined the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free-trade effort involving 12 countries, including the US, Canada, Australia, and several other Asian nations, is encouraging.

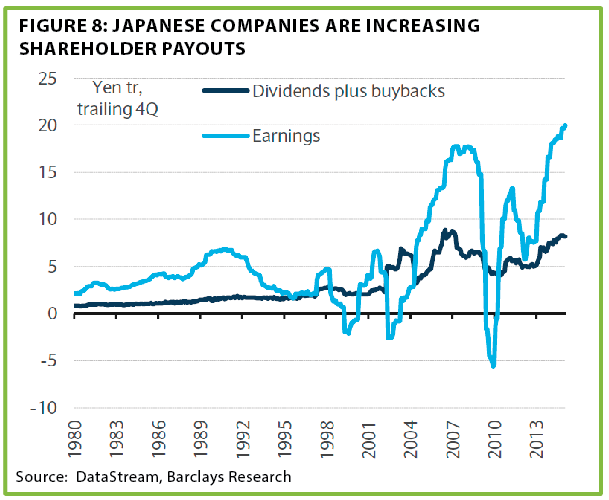

But the most dramatic development is on the corporate reform front. For years, companies in Japan were poorly managed with little regard for shareholder value. Providing lifetime job security for workers (and, of course, managers) was paramount. Lately, though, that has begun to change. As you can see, corporate Japan has begun to increase dividends and accelerate share buy-backs while earnings have exploded.

Unquestionably, the weaker yen has been a tremendous force in boosting profitability for Japan’s exporter champions. This isn’t an absolute positive as companies appear to be pocketing most of the benefit of the cheaper yen rather than cutting prices to capture market share or raising wages by more than a token amount. (The latter development is frustrating Mr. Abe, who is jawboning vigorously for higher compensation; however, the world should be appreciative of the former, otherwise global deflationary trends would intensify.)

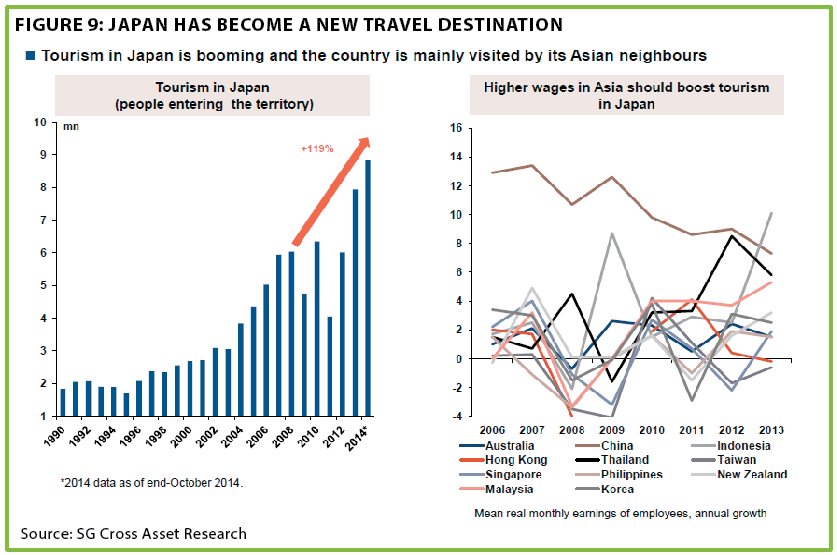

Due to the yen’s evaporation, Tokyo, for so long exorbitantly pricey, has become one of the world’s cheapest major cities. This, along with its storied cleanliness and efficiency, has made it a ragingly popular tourist destination. As figure nine indicates, tourism in Japan is clearly booming.

Driving home the magnitude of the yen’s decline, acclaimed economist David Rosenberg estimates that in real purchasing power it is trading at 1982 levels and is more than 30% undervalued versus the US dollar.

Even the demographic problem need not be insoluble, although Japan’s societal aversion toward immigration is a daunting obstacle. Fortunately, Japan has for years been at the forefront of developing robotics. As the technology has improved, robots are increasingly penetrating everyday Japanese life, not just factory floors. An example is in health/eldercare where robots are being created to calm agitated patients and to lead aerobics classes. Per our friends at GaveKal, there is even a four-legged robo-guide dog in development.

In the factory world, of course, robots have long been present and are almost certain to continue to gain share in functions like precision drilling and welding. The hottest trend appears to "co-robo-ration" where robots work together with humans on production lines rather than replace them. There’s little doubt in the mind of this author and, more significant, the keen minds at GaveKal, that robots will play an ever more important role in Japan’s economic future.

An additional solution for Japan’s dire demographic situation is to integrate women to a greater degree into the workforce. Traditionally, Japanese women have been stay-at-home but that looks to be undergoing a shift reminiscent of what occurred in the US back in the early 1980s.

Another pronounced positive for Japan is the 60% decline in the price of oil. As one of the world’s biggest importers of crude, it’s hard to overstate the benefit of cheaper energy to this heavily industrialized and almost totally resource-bereft island nation.

To conclude this week’s EVA, let’s talk stocks.

Are the days of No-Way-Nikkei over? For twenty-five years, investors could add performance to their portfolios by pretending the Nikkei didn’t exist. As indicated above, even during the recent revival Japanese stocks in US dollars (USD) still trailed the S&P 500—until lately that is. As you can see, this year the Nikkei has been rising—up 10% thus far versus a roughly flat S&P—while the yen has stabilized.

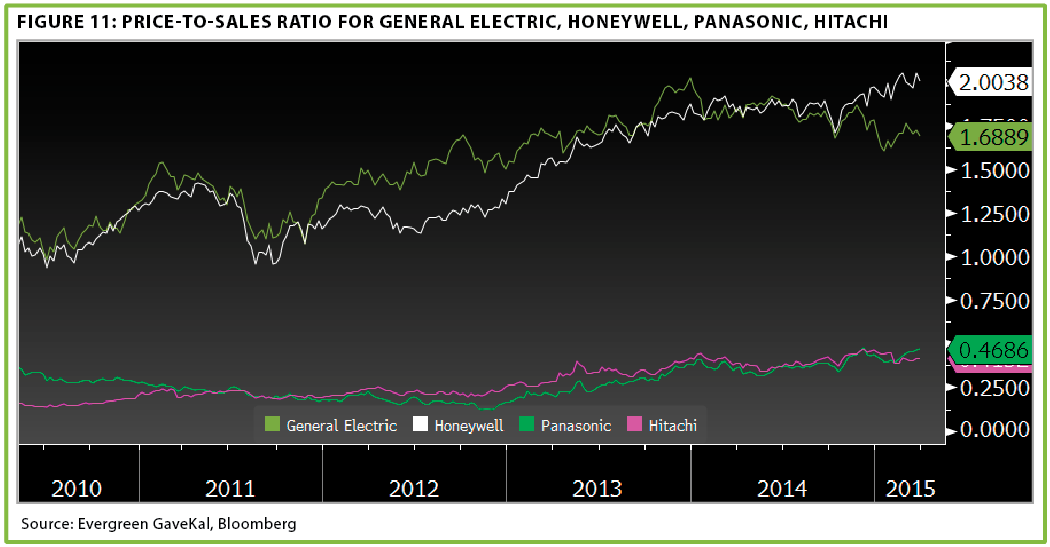

A ramification of this quarter-century bear market, combined with the previously described indifference by corporate Japan to profitability and shareholder welfare, is that the price-to-sales ratio of Japanese blue chips has been ground down to levels reminiscent of the US back in 1982. While US companies like GE and Honeywell trade at multiples of their sales per share, Hitachi and Panasonic sell for fractions of per share revenues.

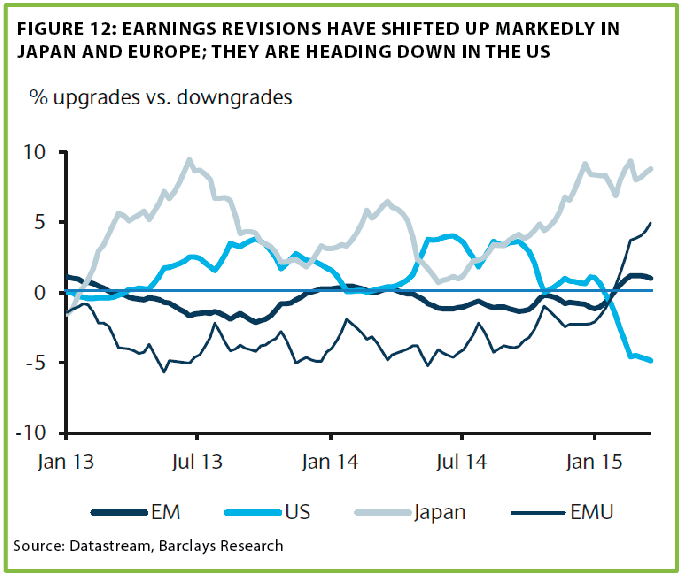

This disparity made some sense when Japan was allergic to making money for shareholders but, with the cheap yen pumping up profits to record highs and corporate governance reforms proliferating, the gap may be poised to close—perhaps dramatically. Japan is forecast to have 15% profit growth this year versus 7% for the US (which is likely high given the probability America is in the midst of a profits recession). Similarly, positive earnings revisions are also running far higher in Japan than in the rest of the world, including suddenly resurgent Europe (EM in the below chart), once again a function of a radically depreciated currency (the euro).

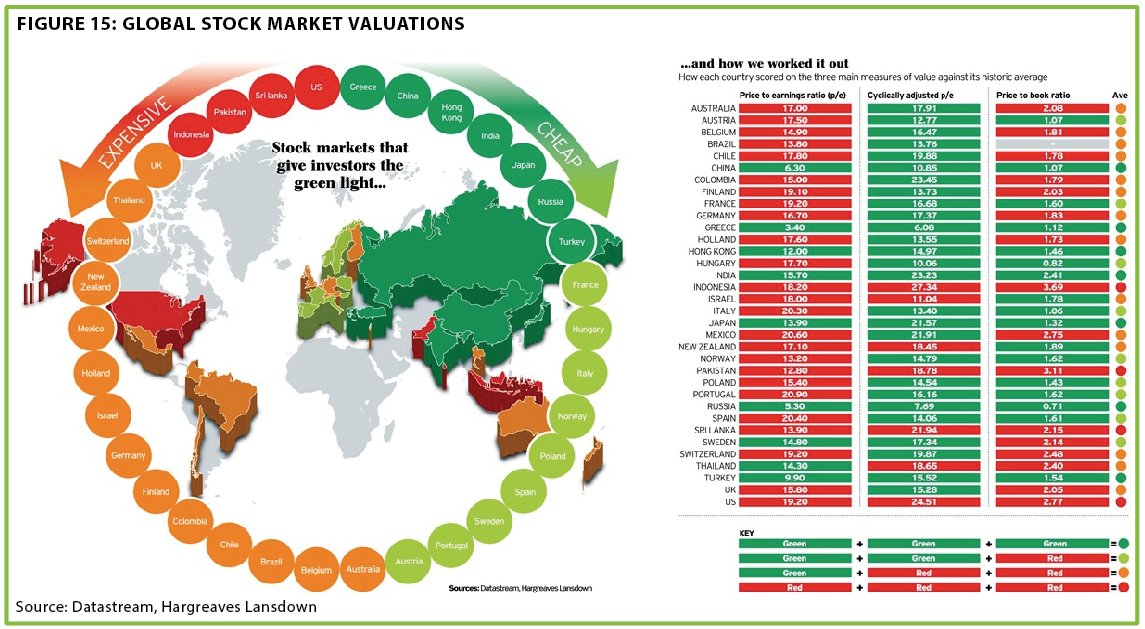

Japanese companies also have gigantic sums of cash laying fallow on their balance sheet, an amount that is roughly equivalent to 50% of GDP. They are beginning to put this cash to work in shareholder friendly ways. Unlike in the US, where share prices are so spendy, Japanese companies buying back stock at prevailing valuations are building, rather than destroying, shareholder wealth. As you can see, despite the rousing rally, Japanese stocks remain bargain priced.

Admittedly, the following graphic isn’t the most sophisticated measure of comparative under- or over-valuation but it does convey that Japan is almost precisely the opposite of the US in that regard. (A word of caution: we would suggest waiting for a pull-back before buying Japanese shares after the recent sharp run-up.)

Okay, there’s almost no doubt that Japan’s mega-bear market has rendered its stock market one of the cheapest in the world but what if Abenomics does a Kamikaze dive? The reality is that much of its success is predicated on trashing the yen by flooding the system with funny money, something I like as much as the fact that my once-beloved Seattle Supersonics now play (and win) in Oklahoma City.

It’s a valid point, but I don’t think Japan has much choice. Unlike in the US and Europe, it truly has been battling deflation. Japan also suffered from an overvalued yen for years, putting its exporters at a significant disadvantage.

Let’s face it: QEs of all types are exceedingly risky monetary experiments that may well prove to have been ill-advised over time. If interest rates ever rise to anything approaching normal levels, most developed global governments (ex-Canada) will be in a world of hurt. In Japan’s case, it won’t take much of a rate rise to eat up all of its tax revenue with interest payments.

At least with Japanese stocks, though, investors are buying a market priced for considerable disappointment and heartache. And if you think QEs are here to stay for another few years, Japan would seem to be one of the biggest beneficiaries.

If so, the Land of the Setting Yen might also be the Land of the Rising Market.