The following article was originally published on March 11, 2025. In today's rapidly changing economic and political environment, some of the events and examples are now outdated. However, the below article provides a still-relevant perspective on the high-level policy goals driving many of the major countries around the world.

“We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow”

— Lord Palmerston

History is again moving through a European land war, the fracturing of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, China sending olive branches to India, a French president ramping up his bellicosity (crushing what little business/consumer confidence remains in France), North American trading arrangements hitting the rocks and Germany ditching fiscal austerity.

Still, living in a world where trade policies and international relations are about as emotionally stable as a hungover teenager is leaving investors frazzled and scared about what happens next. In this report, I will undertake a quick global review of the policy goals in the major countries, if only to establish what these might mean for markets. I start off with France, not because it is the most beautiful of all countries, but because of all the things that happened this week, one of the more surprising might have been President Emmanuel Macron’s televised prime-time speech.

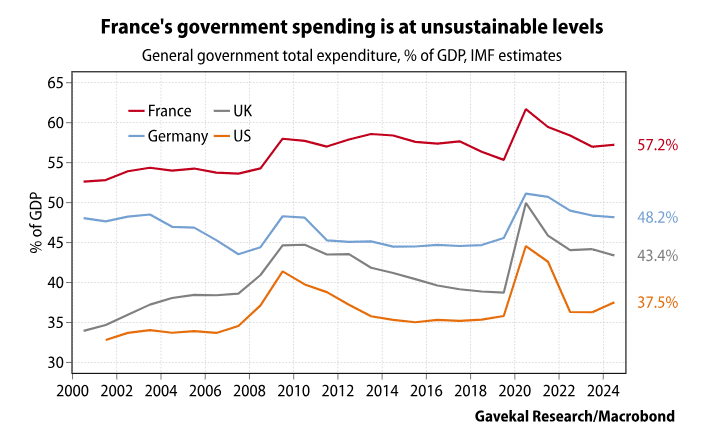

France’s obvious challenge is that the weight of government spending (at 57% of GDP) is out of whack with other major Western nations. Or to put it more succinctly, France can no longer afford its government. If you are the government, this is an existential problem.

In 1919, the solution to France’s precarious financial situation was to say that “Germany will pay”. Today, in Macron’s mind, the solution is that “Europe will pay”; or essentially that a crisis linked to France’s dismal public finances can be avoided through further European integration. It may reflect magical thinking, but the hope is that “more Europe” will solve any, and all, problems.

It is in this context that Macron’s speech must be understood.

If the first principle of political opportunists is to “never let a crisis go to waste” then the Ukraine War, and even more so the likely end of Nato, offers Macron the opportunity to argue the following:

In short, just as the US Civil War, and then the Great Depression, allowed for sharp expansions in the US federal government, today’s Ukraine War offers the same opportunity for Europe. Go big or go home…

Across the Rhine, the situation is rather different as Germany’s elite (usually the owners of Mittelstand) and policymakers have very different goals.

On the policymaker side, the main priority of both the Christian Democratic Union and the Social Democrats is to return to the cozy duopoly that the big two main German parties enjoyed until the emergence of the Alternative for Germany. Many factors have driven the AfD’s impressive rise. The first is unfettered immigration and rising crime levels. Second has been the threat of a war with Russia. Third has been Germany’s suicidal energy policies and the sharp rise in electricity costs. Of these three, the easiest to tackle, by far, are the crazy energy policies. This is why we should probably expect a sharp increase in German spending on nuclear energy, new coal plants, upgrades to the electricity grid, and more loss-making windmills and solar panels.

Meanwhile, for German business leaders, the main goal seems to be to return, as quickly as possible, to a constructive relationship with Russia. After all, Russia is a key provider of most commodities that German industry needs, but it is also an important market for German exports. In this respect, the Ukraine War has been a disaster for industrial Germany on two separate fronts. Hence, by and large, German industrialists are keen to turn the page and get back to business.

Thus, Macron’s hopes of a large European army essentially funded by Germany and standing up to the ogre from the East is unlikely to get much traction in German political and business circles.

The UK’s European policy has always been fairly simple: essentially make sure that neither France, nor Germany, is powerful enough to control the broader continent. Today, with both France and Germany growing ever more irrelevant by the day, it seems that the UK is not quite sure what to do. Perhaps this explains why the UK is just falling back on “institutional memory” with what seems to be the strongest anti-Russian stance of any Western European country. Indeed, opposing Russia is a well-accepted political position across all British political parties—a stance that dates back to the days of the “great game” and the fears that Russian troops would nab India, the British Empire’s prize possession. This stance has hardly wavered, in spite of Russia and Britain having been allies in two world wars.

Interestingly, the fact that Britain has not had to worry about Russian troops barreling down the Khyber Pass for 80 years has not changed the Foreign Office’s strong suspicion of Russia. This is somewhat odd since, of all European countries, Britain is the one with the least to fear from Russia, and the one that has benefited most from the offshoring of Russian savings (Russian oligarchs buying London mansions and sending their children to British boarding schools).

Still, when it comes to foreign policy, Britain has, in recent decades, essentially surrendered any pretense of independence to hold on to the promise of the “special relationship” with the United States. It has meant following the US into disastrous recent wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya. It has also left the UK caught in a bind between a domestic political leadership that continues to back Ukraine to the hilt and a US president who is now busy signaling that Ukraine will soon be on its own.

Amid all of this, where does Britain’s national interest lie? Having a European super state (as proposed by Macron) rise on its doorstep would be anathema to centuries of British foreign policy. Such an outcome would mean that all the military victories achieved by the Duke of Wellington, Douglas Haig and Bernard Montgomery would have been for naught. For Macron, it means the real risk is Perfidious Albion “pulling a Dunkirk” by leaving French troops to (metaphorically speaking) fight it out, while returning to their island to regroup. Put another way, Macron may think that Prime Minister Keir Starmer has his back but there really is little in Britain’s national interest to assume this will be so. It would be especially the case if the US starts to apply pressure the other way.

The first overarching theme coming out of President Donald Trump’s administration seems to be “foreigners will pay”. It might be through tariffs. Or it may be through golden visas. Or through purchases of US weapons. Or even through mineral rights concessions (Ukraine) and territorial transfers (Greenland, Canada). But clearly foreigners are responsible for the various ills the US suffers (fentanyl crisis, deindustrialization, runaway budget deficits, poorly thought-through military adventures) and so foreigners will have to bear a large part of any future financial burden.

This Georges Clemenceau-like thinking may backfire. The post-World War I hopes that “Germany will pay” sowed the seeds of distrust and acrimony. It triggered a collapse in the willingness to invest in Germany, but did not make France any wealthier. Today, the challenge for the US will be to continue to attract foreign capital to the extent that US financial assets have done in recent decades, while also sounding like an increasingly dangerous destination for foreign investors (Trump threatening financial sanctions and confiscation of Colombian assets on his first day in office as a punishment for Colombia refusing to take back two planes’ worth of illegal immigrants).

It leaves Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent with a tightrope to walk since— aside from sticking foreigners with every bill through a mix of carrot (golden visa) and stick (tariffs, sanctions threats)—the clear goals of the Trump administration seem to be the following:

Now, if achieving these goals means that Ukraine ends up getting thrown under the proverbial bus, so be it. And if it means giving off the vibe that the US is “retrenching” into the broader American continent while unleashing a new Monroe Doctrine of sorts, then this may not be a coincidence. The reality—as the Houthis have shown in the Red Sea—is that drone warfare makes patrolling the world’s oceans a more perilous and expensive proposition. The same is true of the new generation of hypersonic missiles like those launched by Russia on the Ukrainian city of Dnipro in November last year.

In short, it seems that the US’s goal is now to build “fortress America” while simultaneously inviting the world’s wealthy to move into the fortress, having, of course, first paid the toll.

Obviously, Russia’s first and foremost policy goal is to win its war in Ukraine. At this stage, President Vladimir Putin needs a convincing victory to justify the expenses in men and materiel. And so, with Ukraine now on the ropes, the willingness to strike a compromise may be dissipating fast. If so, then this war may well be fought to its bitter end.

Russia’s longer-term problem is that, for two centuries, her business model was to extract commodities out of the ground and sell them to Western Europe. Today, the relationship with Europe is essentially broken and the likely desire to press through and impose a total defeat on the Ukrainians means that the European relationship may not be easily mended. Sure, as reviewed earlier, the appetite for a “return to normal” may be high in Germany, but both France and the UK will likely do what they can to prevent such a rapprochement—at least until the Rassemblement National and/or Reform win power in France and the UK. All of this leaves Russia either hoping for a political transition in Europe that won’t happen before 2027 at best (if at all), or alternatively, looking for a new business model. This brings us to the soaring trade between China and Russia since the start of the Ukraine war.

Russia and China have very complimentary economies. Russia produces the raw materials that China needs to fuel its industrial growth, while China now produces the consumer and capital goods that Russia has historically imported from the West (autos, machine tools). Still, how comfortable can Russia feel as it becomes increasingly dependent on China, a country with which it has historically had a challenging relationship?

And this is where India enters the picture. Prior to last year’s Brics summit in Kazan, Putin met one-on-one with Ajit Doval, India’s national security advisor in Moscow. This followed right on the heels of a meeting between Putin and Premier Li Qiang of China. These were two somewhat unusual meetings for Putin, as neither Doval or Li are heads of state. So why would Putin agree to these somewhat “unbalanced” interactions?

Perhaps one answer is Russia’s desire to broker an improvement in the China-India relationship? Indeed, one apparent anomaly on the Asian continent is that Russia and China now get along well, while Russia and India have had a long and strong relationship. Yet as far as the China-India relationship goes, it has not been the case that “the friend of my friend is my friend”.

This is a problem for Russia. If India and China got along better, Russia could conceptually move commodities from Russia to India overland rather than through increasingly unsafe seas, or oceans patrolled by the US navy. Perhaps more importantly, an improved relationship between China and India would unleash an economic boom of epic proportions. After all, between (i) a Russia that produces commodities, (ii) a China that makes machine tools and now offers the cheapest financing in the world, and (iii) an India that has a massive reservoir of under-utilized and cheap labor (unlike China), there would be huge potential benefits from economic integration. A Moscow-Beijing-Delhi economic alliance would essentially be unstoppable.

From Russia’s point of view, pushing in that direction makes ample sense and Putin must have been immensely pleased when, at Kazan, President Xi Jinping announced that he would be pulling back Chinese troops from the contested Indian border and chuffed when Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the restart of direct flights between India and China.

As the country with the world’s largest population, and a diverse one at that (121 recognized languages, 20,000-odd dialects, many age-old religions including Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and Christianity) India’s challenges are numerous and go beyond the scope of this short review. Still, India’s economic challenges include:

A greater economic integration with both Russia and China would, on paper at least, seem to answer many of New Delhi’s economic quandaries.

This is not to say that it will be easy to do. After China’s takeover of Tibet, its support for Pakistan, the 1962 Sino-Indian war and recent border tensions, Indian policymaking circles have a deeply set hawkish stance towards China. Such a defiance fully reflects the broader mood of the Indian public.

Still, one possibly important observation about India is that its business elite is principally made up of “traders” more than “manufacturers”. Perhaps this is a legacy of the British Raj (with the granting of licenses to get anything done)? Or of the fact that while the Brits happily harvested Indian cotton, that cotton was sent back to Lancashire for transforming into shirts that were then sent back for Indians to buy? Whatever the historical cause, to the extent that India’s business elite could stand to benefit, perhaps the hurdles to Chinese manufacturers opening up plants in India—thereby providing jobs for millions—are not be quite as insurmountable as is typically assumed.

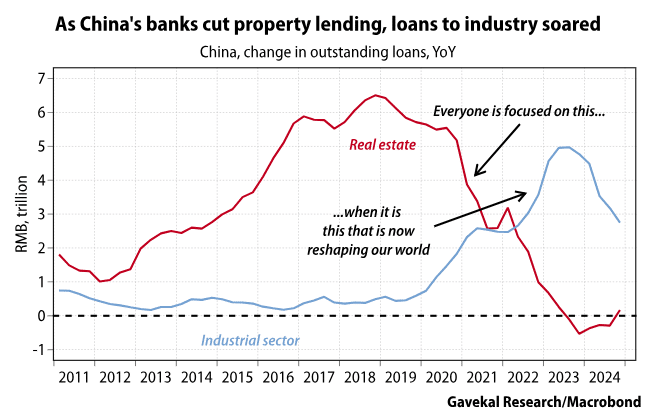

China is likely seeing its third growth model shift in 25 years.

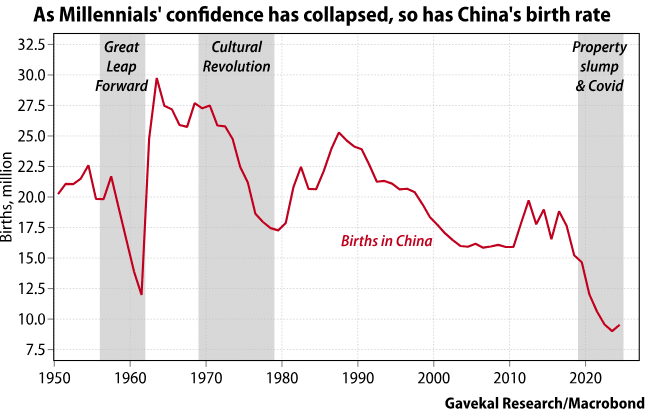

So, in short, from 1998 to 2018, the China story was a real estate story. The 2018 to 2024 story was all about industrial expansion. And the story from now on will be the attempt to boost consumer confidence and consumption. This goal has been made urgent by China’s sudden demographic collapse.

If China is to have a country in 50 years’ time, confidence among Millennials and Gen-Z must be boosted. This means doing more to help repair the balance sheets of young people in urban areas who happened to buy real estate at the wrong time, and with too much leverage. Such a repair job could mean adopting policies to boost real estate prices (which in first-tier cities seem to have bottomed), or a continuation of the unfolding equity bull market. Alternatively, more social transfers could be done.

All of the above developments should leave investors with more questions than answers. For me, the important questions are:

DISCLOSURE: Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.