“We’ve got a monetary policy that still seems like it is in the remnants of a Depression era.”

-JES STALEY, Barclays CEO

“(The) euro area economy is booming and (it’s) not at all consistent with a monetary policy that is appropriate for a destabilizing depression.”

-DAVID ROSENBERG, arguably Canada’s most renowned economist

Another EVA, another chance to read the thoughts of one of the planet’s smartest men, Anatole Kaletsky! This week’s issue is a follow-up to the January 26th edition, also by Anatole, titled “The Big Questions for 2018”. Among those urgent queries is one I personally believe might be the King Kong of them all: is the global bond market on the verge of a meltdown?

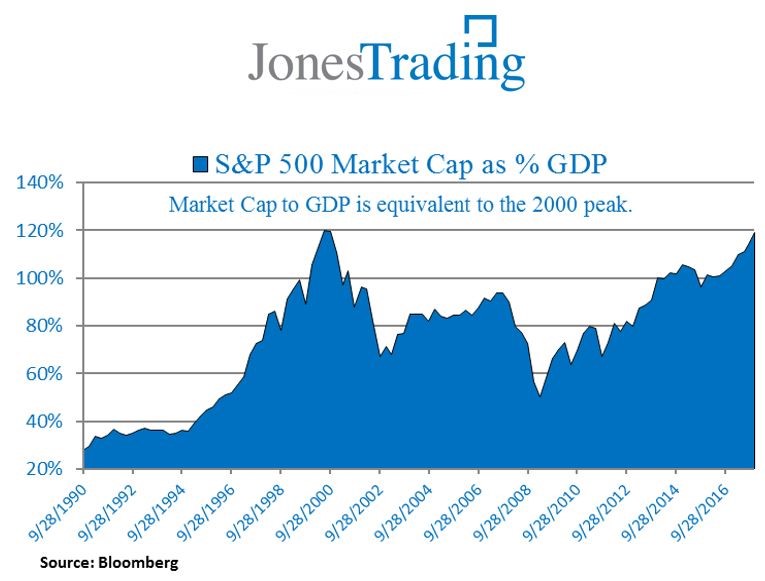

If the answer is yes—and even the ever-bullish Anatole allows for the possibility—the implications are enormous. How many times have we heard that stocks are cheap relative to bonds? This logic conveniently ignores that share prices, especially in the US, are terrifyingly expensive based on nearly every other measure. Here’s one that has long been Warren Buffett’s favorite barometer of under- or over-valuation.

As you will read below, Anatole points out that mid-2016—when yields on 10-year US treasury notes crashed down to 1.3% and $12 trillion of bonds around the world had negative rates—was “arguably the greatest financial bubble of all time”. In my mind, he was right, and actually still is, and there’s really no arguing about it. But what he doesn’t point out is that there remains nearly $10 trillion of bonds with negative interest rates. In one of the most extreme examples of the absurdity of this money for nothing—or less than nothing—era was a junk bond that came to market in Europe late last year with a negative interest rate!

By merely focusing on the insane valuation of bonds, primarily outside of the US, what is missed is the impact this phenomenon has on virtually everything else. As noted above, the Lilliputian level of interest rates has been continually used as a rationale to justify extreme stock valuations. But they have also directly impacted the price of real estate, driving property values up to, or even beyond, 2007 levels. This utter collapse in the cost of money is the prime reason Evergreen has dubbed this the Biggest Bubble Ever (BBE) across the major asset classes of stocks, bonds, and real estate.

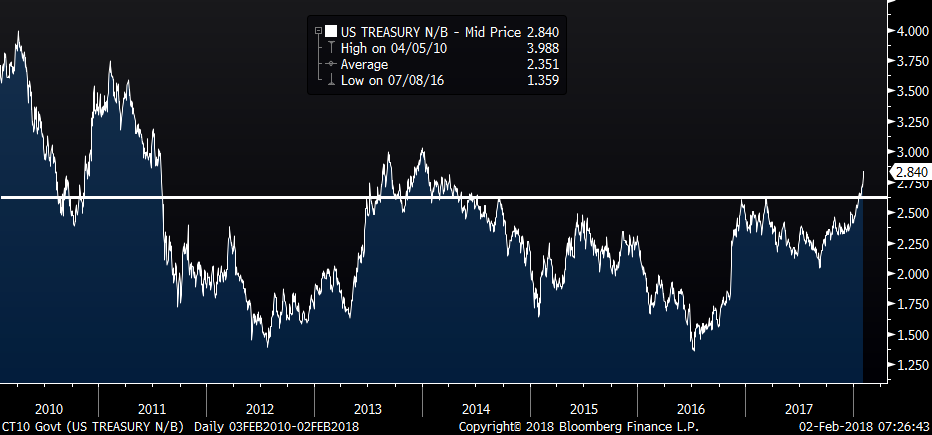

Consequently, I believe the answers to Anatole’s five bond questions are of paramount importance to all investors. One point he makes, with which I completely concur, is that the 2.60% yield threshold, or thereabouts, is crucial. This high point in rates has consistently held ever since 2013’s “taper tantrum,” when then Fed-head Ben Bernanke floated the trial balloon of ending Quantitative Easing (QE) III. As Anatole also notes, there is no “resistance”, in technical analysis parlance, from around that point until 3% where yields topped out during the tantrum. Further, because countless investors (and computers!) have been eye-in-the-sky focused on 2.6%, a decisive break was highly likely to create a self-fulfilling selling frenzy. That upside penetration became apparent last Monday, and sure enough, the yield on the 10-year has sprinted to 2.85% as I write these words. We’ve updated Anatole’s chart to highlight the significance of this development.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

There are such things as false break-outs and this could certainly be viewed, in the fullness of time, as such. But, frankly, I doubt it. Another contention of Anatole’s that I completely agree with is that if the aforementioned 3% level is subsequently penetrated—admittedly, a very big if—“US financial conditions will be transformed”. As past EVAs have conveyed, perhaps ad nauseum, the Planet Earth has added $70 trillion of additional debt over the last 10-to-12 years. US consumers have actually paid down a bit of their IOUs, mostly via mortgage walkaways, but the corporate and government sectors have been merrily piling on the debt. Consequently, the bite of higher interest rates is likely to be barracuda-like in its ferocity.

However, a belief of his with which I very much disagree is the notion that there isn’t a lot of risk of 10-year German government bonds (bunds) breaking above 1%. As of today, those yields have already raced up from 0.6% last week to 0.77%. What makes this interest “rate” utterly absurd (like so many things these days) is that Germany’s economy is roaring, at least by its staid standards. This boomlet is not just a function of rates that should only be used to combat a deep depression but also a euro that is way too cheap.

In my opinion—which could, of course, be wrong—over the next year or so, the 10-year bund rate is going to break through 1% and sprint toward 2% (assuming there isn’t a financial market crisis first). The European Central Bank (ECB) is already in the process of cutting its bond purchases in half. Its blind buying has been the only reason yields are so ridiculously low in Europe. There is mounting pressure on the ECB to halt bond buys altogether as a growing number of policymakers are waking up to the dangers of asset prices going ballistic, once again stoked by virtually non-existent interest rates.

Let me conclude my lead-in with a couple more “agrees”: international stock markets are more attractive than the US after seven years of badly lagging. However, this is not to say they will be immune to a paroxysm of selling in global bond markets, should recent weakness intensify (with this week’s worldwide stock market swoon illustrating the linkage). It also makes sense to me that considering the healthy current economic momentum in most countries, the greatest threat to the bull market in almost everything—almost everywhere—is a bond market melt-down. And, with so much money devoted to “risk parity” strategies, which theoretically hedge stock market downside via leveraged bets on bonds, this could be the ultimate double-whammy.

Regardless of the timing, I’m convinced that we will eventually be looking at an episode that looks an awful lot (in both senses of the word "awful") like October, 1987. For those too young to remember (I’m definitely, and unfortunately, not), that was the month stocks fell 30% nearly overnight. But, no worries, we are constantly assured that can’t happen again.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

THE 5 BIG BOND MARKET QUESTIONS

By Anatole Kaletsky

With 10-year US treasury yields near the point of breaking out above their 2017 high of 2.6%, financial commentators around the world have suddenly become obsessed with a single question: Have bonds finally entered a bear market, after the multi-decade bull trend that started back in October 1981, when the 10-year yield peaked at 15.8%?

There is only one sensible answer to this debate: Who cares? No agreed definition exists of what might constitute a bond bear market, comparable to the conventional -20% peak-to-trough decline in equity parlance; so it isn’t clear whether the question even means anything. If a bear market is defined simply as a persistent sequence of lower lows and lower highs, then the bear market in bonds actually began 18 months ago. After all, it is almost inconceivable that bonds will ever again see the ridiculous levels of June 2016, when a third of all developed market government debt, almost US$12trn by face value, was trading on negative yields, in what was arguably the greatest financial bubble of all time.

So instead of quibbling about semantics, it is worth asking five more important questions as yields threaten to break through their 2017 high:

None of these questions can yet be convincingly answered. But if US bond yields keep rising, these are the issues that will dominate investment performance in all global markets, and we will doubtless return to them many times in the months ahead. For the time being, here are some quick observations to help think about these five points:

1. If the 10-year US treasury yield moves decisively above the 2.6% double top created in December 2016 and March 2017, the next significant high will be 3% (see the chart below). If yields remain below this 3% ceiling, it can be argued that interest rates have not changed very significantly. But if the 3% ceiling gives way, then the trading range that has prevailed since the summer of 2011 will clearly have been broken, and US financial conditions will be transformed.

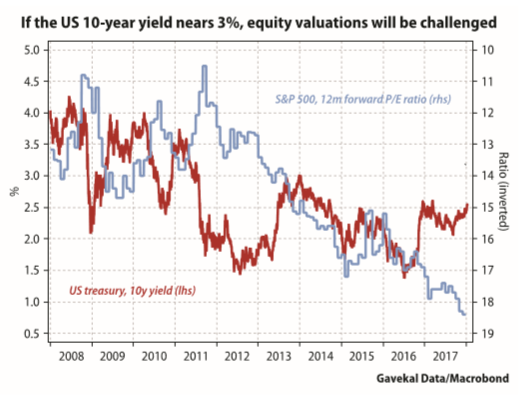

2. If the 10-year US treasury yield rises into the 2.6-3% range, current US equity valuations will be challenged, since the forward P/E ratio on the S&P 500 was around 15 when yields last exceeded the 2.6% level in 2014. In this range, the equity bull market could still continue, driven by investor rotation out of very long-duration equities such as technology stocks with high P/Es into shorter-duration cyclical stocks (i.e. lower P/E “value” stocks) which are trading on much less demanding multiples. But if the 10-year yield rises much above 3%, valuations anywhere near present levels will be hard to sustain and US equities will probably suffer a deep correction.

3. If 10-year US treasury yields rise above 2.6%, or even 3%, Japanese or German bonds will doubtless also rise, especially if the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan continue to taper. But it is extremely unlikely that 10-year bund yields will move above their post-2014 ceiling of 1% or 10-year Japanese government bond yields above their post-2014 ceiling of 0.6%, since there is no prospect of either the ECB or the BoJ hiking short rates above zero for at least another year, and possibly much longer.

4. The discount rates applied to future European and Japanese profits should be based on bond yields in euros and yen, not in US dollars. So if 10-year yields in euros and yen remain below 1% (and they will probably be quite a lot lower), European and Japanese equity multiples should keep moving higher, even if US equity valuations suffer from higher US dollar interest rates. A moderate and gradual rise in US bond yields should therefore drive further equity rotation out of Wall Street into European and Japanese markets. If, however, the rise in US bond yields becomes so severe that it triggers a deep correction or full scale bear market on Wall Street, equities elsewhere are unlikely to remain unscathed.

5. Finally, it seems clear that the main threat to equity valuations in the year ahead is a steep rise in bond yields, not a slowdown in economic growth. If this is indeed the case, then long duration bonds are no longer an effective hedge against equity risk. If the world is moving from a deflationary to an inflationary or expansionary environment, equity exposure needs to be balanced with cash, commodities, gold or other inflation hedges. Bonds, far from stabilizing the portfolio, could soon become an amplifier of equity risks.

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.