“Although macroeconomic forecasting is fraught with hazards, I would not interpret the currently very flat yield curve as indicating a significant economic slowdown to come.”

–BEN BERNANKE, Former Fed Chairman in a March 20, 2006 speech

“It was popular to play down the significance of the inverted yield curve in 2000 and 2006, but on both occasions, the bond market's warning was eventually vindicated."

–The Long View column in the Financial Times, March 30th and 31st, 2019

“Nothing sedates rationality like large doses of effortless money."

–WARREN BUFFETT

BUBBLE 3.0: A BLAST FROM A BUBBLE PAST

Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time. Please see important disclosure following this article.

A Blast from a Bubble Past. Being old—like north of 60—doesn’t come with many advantages. However, in the investment game it does have at least one: being “mature” enough to remember past financial and business cycles. In the case of this geezer, I have recently been having repeated flashbacks of the fateful year of our Lord, 2000.

Accordingly, in this month’s latest installment of “Bubble 3.0” I’m harking back to Bubble 1.0, the infamous tech boom that ended in one of the most punishing value destructions of all-time. One could even credibly assert, as I have in the past, that it was the long-ago tech bubble of the late 1990s that set off the chain of events which led to Bubble 2.0 and, if I’m right, our present bout of rank speculation.

For many years, there weren’t a lot of similarities between the first and third manias but at least since 2017 that’s been changing. As Mark Twain supposedly quipped, history doesn’t repeat but it does rhyme and there seems be a lot of rhyming going on these days.

One of the reasons I’ve heard in the past as to why what we are going through now isn’t another bubble in US stocks was because the IPO* market has been subdued. For many years, that was true even though US stocks, as measured by the price-to-sales ratio, one of the best market valuation tools, had equaled or even exceeded the dizzying heights seen in late 1999 and early 2000. This metric is especially worrisome on a median (i.e., the mid-point of the S&P 500) price-to-revenue basis.

*IPO stands for Initial Public Offerings, or new issues.

S&P 500 Price/Sales Ratio

S&P 500 Median Price/Sales Ratio

Source: Ned Davis Research, May 22, 2019

Source: Ned Davis Research, May 22, 2019

It may have been a fair point that you can’t have an old-fashioned bubble without an IPO feeding frenzy. Wall Street has always excelled at creating the fuel—not to mention the hype—that stokes these strange episodes where greed fully obscures the reality that most new issues end up being losers.

Lately, one has to be in full bubble denial not to recognize the mania that has once again engulfed the market for new issues. Three recent offerings underscore the 2000 echo feature of this latest infatuation with IPOs. While there are some other worthy candidates, Uber, Lyft and Beyond Meat deserve special mention. For one thing, all three are totally unacquainted with that dated concept of making money. For those, like me, who are chronologically-advanced enough to remember the late ‘90s, that was also an era when profits were an after-thought. The 1999/early 2000 class of going-public companies were able to command what were then lofty valuations by touting metrics like “number of eyeballs” or “total addressable market”. Profit considerations were ignored. It was all about attracting as many users and/or spinning fantastical tales about the sheer size of the potential revenue pool.

Well, here we go again. Over 80% of IPOs coming to market currently are earnings-free, the highest since—you guessed it—2000. In actuality, most are losing copious amounts of money, as was also the case nearly 20 years ago. However, one big difference is literally that—today’s crop of new offerings are much bigger than during Bubble 1.0, and so are their operating losses. Uber, for example, was losing a cool billion per quarter before it went public. If nothing else, you’ve got to give it credit for consistency because it’s maintained that pace since its May 9th public offering and its own projections showing that continuing.

Like its fellow recently-listed ride-hailing service, Lyft, Uber has also been losing money in a new and different way. Right out of the gate, it plunged 18%, generating about $14 billion in lost market value for its shareholders, before rallying back with the overall market to only about a 6%, or $5 billion, loss. Actually, Uber was generating valuation erosion even before it went public at a market capitalization of $80 billion; that was a mere $40 billion below where it was supposedly to be valued—at least until Lyft did a reverse-lift almost as soon as it started trading. At one point, Uber’s rival was down 33% for an overall market value shrinkage of $8 billion. Between the two, they have produced $8.5 billion in losses since making their public debuts.

For those rare market professionals who were actually in the game back in 2000, this is another retro event. That great equity bubble—arguably one that even exceeded the legendary 1920s stock market insanity—began its equally great deflation when several high-profile IPOs bombed. But that’s not to say that all IPOs are crumbling right now. The third highlighted new issue—Beyond Meats, ticker BYND—is indicative that speculative juices are still flowing freely these days.

Initially priced at $25 per share, Beyond Meat’s brief trading history indicates that its underwriters may have priced it a tad too conservatively. On Monday of this week, it briefly hit almost $168, for an aggregate market capitalization of roughly $10 billion, before falling over $40 the next day.

Now, an $8 to $10 billion valuation isn’t eye-popping for a new company these days, especially compared to Uber’s $75 billion market cap. But an investor would be forgiven if his or her eyes watered a bit considering that Beyond Meat produced all of $88 million in sales last year. What about profits you might dare to ask? Well, it’s beyond me why anyone would be such a stickler for earnings when a company can convert the humble pea into something as tasty as a juicy, albeit faux, hamburger.

(Caveat BYND emptor: At the risk of being considered of the stickler type, my wife and I were intrigued by the idea of a tasty and healthy alternative to meat. Thus, we dutifully headed to Bristol Farms to buy a package of both their sausages and meat patties. The first thing that jumped out at us was how high-fat they were, especially the burgers. Now, maybe it’s “good” fat, like avocados, but still 20 grams is another eye-opener. As far as the taste goes, the sausages were decent but the patties were a different story. Maybe I over-grilled them but even our dogs wouldn’t eat them and they’ve never been nitpickers when it comes to anything vaguely resembling meat. In fact, one of them recently consumed a tennis ball whole, leading to a $7000 emergency surgery bill. Thank God for pet insurance!)

Less well known than the above IPO trio are issues such as Coupa Software, now trading at a P/E of 642 (don’t look for missing decimal; there isn’t one), Zoom Video (P/E 1000, short-hand for infinite), Blackline (it must have a touch of black on its bottom-line given a P/E of 395), the Trade Desk (a screaming bargain at 70 times earnings) and Zscaler (at a much less bargain P/E of 686). Of course, these must all be based on trailing earnings—or losses. No doubt, based on future profits, like out somewhere around 2030, this collection of exceptional growth stocks must actually be reasonably valued.

Ok, even a rabid bull might concede, conditions in the IPO market are somewhat overheated. But what about those that have longer trading histories, in some cases pre-dating the original tech boom-cum-bust? One of that old guard is Adobe, a fabulous service most of us use, knowingly or not. Unsurprisingly, it trades at just 14 times. The problem is that it is times sales, not earnings. Its P/E is a rather generous 50, which is particularly notable based on a market value of $135 billion due to the fact it’s exceedingly hard for a company that large to grow fast enough to justify either 14 times sales or 50 times earnings.

On that point, Scott McNealy, former CEO of one of the biggest supernovas of Bubble 1.0, Sun Microsystems, was famously quoted as saying, in the wake of the tech implosion, that it was nonsensical to pay anything like 10 times sales for a large company. This is a partial excerpt of his scathing comments from 2002: “At 10 times revenues, to give you a 10-year payback, I have to pay you 100% of revenues for 10 straight years in dividends…What were you thinking?”

Today, clearly, investors are obviously oblivious to such warnings. The list of companies at 10 times sales or more is a long one. In addition to Adobe, there is Salesforce.com (CRM, 10 times), Cyberark Software (CYBR, 14 times), HubSpot (Hubs, 14 times), MongoDB (MDB, 29 times sales!). In the interest of saving time and space, I’ll show just the following ticker symbols (you can look up if you care): NEWR (13 times sales), NOW (17X), PAYC (21X), TEAM (23X) TWLO (26X). VEEV (24X) and WDAY (16X). (Thanks to the ultimate bubble-buster, Fred Hickey, for these factoids.)

One major divergence vs 2000 is that these outrageous valuations go well beyond tech. For example, Wingstop (WING) a purveyor, as its name implies, of chicken wings and other animal appendages, trades at a high-flying P/E of 90 and 14 times sales. Planet Fitness (PLNT), the gym operator, sells at a weighty 50 times earnings and 11 times sales. Chipotle Mexican Grill (CMG) is another restaurant chain selling at a tech-like P/E of 56.

Frankly, I’ve never seen so many companies, even in 2000, trading at prices that are in, most cases, nearly certain to produce return-free risk. But there is some very good news, in my opinion, for disciplined and discerning investors. It’s a message that was conveyed in our January 3rd special buy-alert EVA, in which we expressed our belief a powerful rally was looming. In my view, it bears repeating, including to the perma-bears: This is a two-tier market.

Just as was the case in 2000, there are a multitude of reasonably valued companies. In some cases, these entities are so detested that they are trading truly at give-away prices. As usual, and as was also true in early 2000, energy is the poster-child for the malign neglect. Rarely has the energy sector represented just 5% of the S&P 500’s market value. You can see below that this is one of those times. Only during the nuttiest days of Bubble 1.0 did energy trade even cheaper on a relative value.

Energy Sector as a % of the S&P 500

Additionally, several of the bluest chip energy names yield 5% to 6% with extremely well-covered dividends. The prevailing justification for this cheapness is that we now live in an increasingly digital world and that energy is becoming obsolete. This is almost a (hydro) carbon copy of the mindset that prevailed back in early 2000 when the energy sector was viewed as the ultimate embodiment of “old economy”. Not long after the tech crash, however, the realization was that all those server farms being built—even back then—by Microsoft and others were huge consumers of energy. From the end of the first quarter of 2000 until the fourth quarter of 2007, in the dying days of Bubble 2.0 (housing), energy produced a total return of 228% vs minus 54% for the tech sector.

Another epiphany may be close at hand. Our partner firm Gavekal recently held its annual retreat in Hong Kong. Analysts and strategists from all over the world convened to discuss their strongest convictions and views. One of the dominant themes to emerge from their conclave was that markets are underappreciating, once again, how much power the digital world consumes. Per leading tech consultant Gartner, the number of connected devices is set to double in the near future, leading global internet traffic to triple over the next five years. According to Charles Gave: “If the Internet-Big Data complex were a country it would already be the third largest electricity consumer in the world, after the US and China.”

With the crypto currencies like Bitcoin coming back from the dead, you may recall that mining for them is highly energy-intensive. It’s estimated that the current global production of the cryptos amounts to the equivalent power usage of over six million US homes.

Renewables will undoubtedly be the fastest growing source of energy to power the explosive growth of all things digital, a trend that is likely to become even more viral as the “internet of things” hits stride over the next few years. However, the reality is that fossil fuels, along with nuclear, will provide the primary baseload for the planet’s energy needs for years, if not decades, to come.

Speaking of cryptos, which are enjoying a robust bounce, this is a further commonality with the 2000 dot.com blow-off then blow-up. The chart of Bitcoin overlaid on the NASDAQ circa the late 1990s is remarkably similar. However, as with everything involving Bitcoin, it has happened in accelerated time.

As previous EVAs have observed, Bitcoin is likely the signature micro-bubble within this latest overall bubble, just as the NASDAQ was THE epicenter of the late ‘90s equity craze. For sure, this time the Bitcoin bubble has had to compete with many others for that title. This is due to the fact interest rates have been largely exterminated globally, causing a mad rush into higher-risk assets and the better returns they are hoped to deliver. Just as the “NAZ” was dead money for over a decade after it crashed, the same is likely to be true of Bitcoin and the other cryptos, despite what will almost certainly be some dramatic bear market rallies.

Yet an additional parallel with 2000 is the regulatory attack on tech. In the late ‘90s, it was pretty much only Microsoft that was big enough to attract the government’s scrutiny and ire. The anti-trust case against MSFT started in 1998 and opening arguments began in 2001. But between its share price being grossly inflated plus the fines and restrictions placed on it, the damage was done. As a result of the various handcuffs it was forced to wear, as well as missing some critical new product trends, our local software giant lagged the S&P 500 by 64% from 12/31/99 through 12/31/12, falling 40% vs the market’s 24% rise.

Ironically, today, the company Bill Gates built is no longer in the US government’s crosshairs. But, as Michael Johnston highlighted in last week’s EVA, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Google definitely are. Because these four represent about 12% of the S&P’s total value, anything that causes a repeat of what Microsoft experienced two decades ago is a big threat to the index—and all those who blindly mimic it. (Note, Evergreen owns two of the above issues for many clients but at less than a market weighting.) Fortunately, three of the four trade at reasonable P/Es, unlike so many of their smaller competitors. Yet, should government interference cause flat or, God forbid, falling earnings, they may still struggle for a time.

Next up on the echoes of 2000: The war then vs the war now. In fairness, the war on terror didn’t begin until September of 2001 when the tech bust was well underway. However, it certainly intensified the carnage. Today’s war is, mercifully, not of the shooting variety but it is nonetheless most dangerous, particularly for big tech. This is because few industries have benefited more from sourcing their products in low-cost countries like China and selling everywhere, including, of course, to China itself. Consequently, tech is at risk of losing both its access to inexpensive production and one of its most lucrative end-markets, as are many US multi-national companies.

As Michael also noted last week, tech earnings have been vitally important to the US market. In fact, they have debatably been one of the two main reasons why US stocks have dramatically outperformed global equity markets over the past decade, along with buybacks. Thus, anything that threatens tech’s exceptional earnings record is of profound consequence to the overall US market.

The enormous and consistently rising earnings from the titans of tech—which politicians like Bernie Sanders and others allege are due to monopolistic characteristics—has been one of primary forces behind the higher highs seen by S&P 500 profit margins over the last twenty years. (Another factor was the persistent drop, until lately, in labor costs but that tailwind is turning into a headwind.) This profitability surge has also been a prime driver behind the US market’s exceptional outperformance of overseas indexes. This is, in turn, one of the key reasons the price-to-sales ratio has risen back to near the peak seen in 2000 (or beyond on a median basis), per the first chart in this EVA.

On the buyback topic, the May 17th EVA pointed out the extraordinary “coincidence” of the Fed creating $4 trillion of fake money, corporate America taking on $4 trillion of new debt and the $4 trillion of buy-backs that have occurred. This has also been another unique aspect of our country versus the rest of the world. You may not be aware, and I wasn’t until recently, of one of the probable causes of this stock buy-back binge.

In 1995, just as Bubble 1.0 was ready to gargantuanly inflate, then President Bill Clinton signed a bill making executive compensation over $1 million non-deductible for tax purposes. But here’s the key part: incentive compensation, like stock options, was exempted. Thus was ushered in an era of massive stock and option awards, leading to lavish pay packages the likes of which had never been seen before and which have only gotten more egregious since. Understandably, this also caused stock buy-backs--which generally increase earnings per share and, in turn, share prices—to look irresistible in the eyes of senior corporate executives. Once the Fed reduced interest rates to negligible levels, it made it equally irresistible to borrow trillions to push this process into hyper-drive. (As previously written, this is such a crucial theme it deserves its own “Bubble 3.0” chapter, to be keyboarded in the not too distant future.)

But there are threats to this bull market aphrodisiac with politicians as diverse as Elizabeth Warren and Marco Rubio assailing the diversion of such large sums away from efficiency-enhancing investments. They believe, as does this author, that multi-trillion dollar stock buy-backs have been one of the prime causes of the long-running erosion in corporate America’s productivity. Similarly, during Bubble 1.0, Warren Buffett was railing against the exclusion of stock option costs in earnings calculations. As he said at the time, “If options aren’t a form of compensation, what are they? If compensation isn’t an expense, what is it?” It will be very, very surprising if there isn’t a vicious political backlash against the games that CEOs and CFOs have played to enrich themselves and their shareholders during this cycle. The latter will likely find out that in many cases the inflated share prices were temporary. By that point, though, most of the senior executive stock options will have long been exercised and sold.

The last flashback aspect I’m going to bring up—though there are many more I could—relates to the yield curve and current economic conditions. As most EVA readers are aware (I hope!), this refers to the difference between short-term and long-term interest rates. The former are normally lower than the latter. Presently, as happened in 2000, the yield curve is definitely not normal. Portions of the treasury yield curve inverted last year and it has become even more so recently. When it inverted early in 2000, it stayed that way for the full year even as stocks and the economy started to lose altitude, a situation we are seeing once again.

The culprit, as usual, is the economy. For at least six months, we’ve been making the case that business conditions were softening. This has been in contradiction to most of the mainstream media’s sunny view of the US economy. We’ve even read recently about the “robust global economy” despite the fact that overseas economies have been sucking wind for over a year. As you can see below, the OECD (i.e., developed country) Composite Leading Indicators, one of the critical measures of the planet’s economic health, is in a steep decline. In the US, the key Manufacturing PMI just hit its lowest level since September, 2009, when the Great Recession was still raging.

There is a plethora of factoids I could relay on the US slowdown but that would take up an entire EVA so here’s just a brief recap of some of salient items, courtesy of David Rosenberg, for my money North America’s best economist (all figures are year-over-year):

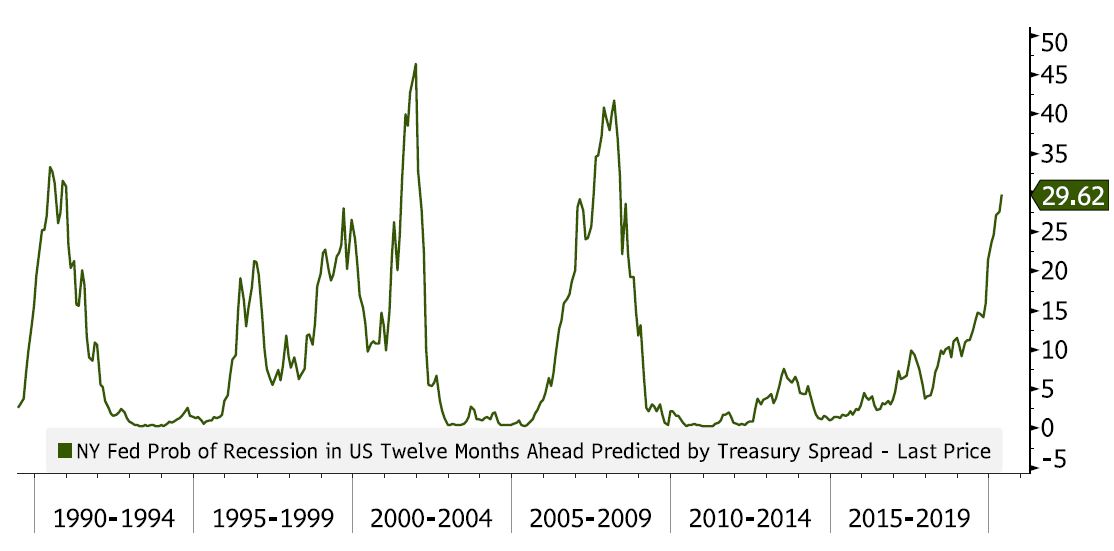

Perhaps all of the above, and much more, is why the NY Fed’s recession risk model continues to soar. As you can see, once it hits the upper 30s, a recession becomes highly probable.

What many have long viewed as proof-positive that the US economy was just fine has been the jobs market—note the words “has been”. As you may have read, the employment report for May released last week was shockingly bad. Many are dismissing this as an aberration but, as we’ve been repeatedly warning for months, the jobs market’s leading indicators, such as overtime pay and temporary employment, have been steadily eroding. Even before last Friday’s stunner, regular readers of The Economist should not have been surprised by the adverse jobs number based on that magazine’s well-known curse of its cover stories. This was the front page of its May 25th issue:

Going back in time once more to early 2000, it was nearly inconceivable then that a recession would begin a year later. America was experiencing a legitimate economic boom with growth far faster than it has been throughout our current expansion. Consumer confidence was at all-time highs with nary a cloud in the economic skies.

Moreover, it was not debt-driven pseudo-prosperity. The Federal government was actually running a surplus. By contrast, per the King of Bonds, Jeff Gundlach, the US government has been running deficits in excess of 7.7% annually to produce just 3.4% nominal growth in GDP over the past 13 years. (Nominal GDP includes inflation and therefore is not the “real” GDP usually reported; that number has been about 2% per year during this expansion). Yet, despite how exceedingly vigorous the US economy was in early 2000, the next recession started in the spring of 2001. Note this was six months prior to the horrific 9/11/01 terrorist attacks.

Besides the debt-driven aspect of today’s global economy, another glaring dissimilarity has to do with interest rates. An investor who was leery of the stock market in those days could shift into high grade bonds or CDs yielding 6% to 8%. (Weren’t those the days?!!). Now, with the best rate on CDs in the mid-2s and most high-grade corporate bond yields sub-4%, investors in financial assets feel forced to stay more heavily exposed to stocks than their age might dictate. And if they want to make money in a market that has basically gone nowhere for almost a year and a half, since late January of 2018, they may feel compelled to chase the crazy overpriced momentum names mentioned above.

This is where studying 2000 could really save the day. By March of that year, there was a giant valuation chasm between the shrinking number of popular stocks and those that had been out of favor for at least two years. Investors who shifted from growth issues into value shares were spared the first two years of the looming three-year bear market and the terrible toll that so many suffered by being heavily exposed to the NASDAQ as it vaporized by nearly 80%. As you can readily see from the chart below, it’s definitely a case of deja vu all over again.

Even though this is heresy to many, the Evergreen view is that a simple buy-and-hold approach with an S&P 500 index fund won’t cut it; actually it hasn’t for a while, like the last almost 20 years. Of course, two decades isn’t really that long…at least in cosmic terms. As mentioned numerous times in these pages, the S&P has only returned 5.6% per year since 12/31/99, slightly less than you could have realized on a diverse portfolio of investment grade corporate bonds over that timeframe, and, of course, with far greater risk.

Just as in 2000, allocating away from the most bubble-infested parts of today’s stock market is essential, as is selling into rallies and buying into weakness. There was definitely buyable weakness late last year and it looked like we might see another opportunity had the May dip continued. However, the Fed’s hints that it might start cutting rates this summer catalyzed a new snappy rally. The market seems convinced that an easing Fed is unquestionably bullish but question that belief I must do, once more going back to Bubble 1.0. As 2000 drew to a wobbly close both for stocks and the economy, the Fed opted to cut rates by a dramatic ½% in early January of 2001. The beleaguered NASDAQ surged 14% IN ONE DAY. Now, that’s a bear market rally! The problem is that it continued to decline after that, by almost 60%.

The same thing happened in 2007 and 2008, as the Fed frantically cut rates reacting to the housing bubble and economic meltdown it never saw coming, to no avail. Consequently, perhaps the vaunted “Fed put”—essentially, dramatic easing to avoid market mayhem—doesn’t work once a full-blown bubble has developed.

Please allow me to end this latest installment of Bubble 3.0 with this image, also from Fred Hickey, and the question it asks: Is an Accommodative Fed Bullish for the Stock Market? Put on your robe and grab your gavel—you be the judge.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.