“We don’t know when the bear market will hit but we do know that because it’s been so delayed, it’s going to be much worse when it happens.”

-From a recent conversation with one of Evergreen’s wisest and wealthiest clients

“The single most reliable valuation measure we’ve ever tested or introduced is the ratio of non-financial market (value) to corporate gross-value added (including estimated foreign revenues). Last week, that measure pushed into the top 0.5% of all historical observations.”

-Market strategist and money-manager JOHN HUSSMAN, in his June 27th newsletter

First, please accept my apologies that this EVA issue, based on my in-progress book titled “Bubble 3.0”, is out of sequence. My intent was to run it as a later chapter in the actual book, but I was concerned that if I didn’t run it soon as part of our newsletter, I might miss my chance to create this on a before-the-fact basis. If you are wondering what that “fact” might be, it relates to my suspicion that we might be in the final act of what I have formerly referred to as “The Great Levitation”.

Just to be glacier-lake-clear, I’m talking about what has been the modus operandi for years now by nearly all of the world’s masters of monetary mayhem machinations: driving asset prices to unprecedented levels and hoping like hell it produces a strong economy. Just a few months ago, it looked like maybe—very belatedly—they’d pulled it off. Early this year, the financial media was constantly chattering about the “synchronized global expansion”. However, you may have noticed that phrase has gone missing in recent months.

Speaking of the financial media, this edition of the Bubble 3.0 EVA series involves an imaginary interview between a fictional TV personality and a certain Bellevue-based curmudgeon of a money manager. As you will see, she pulls no punches in pounding on me for my premature premonitions of corrections, bear markets, and, even, crashes. It’s my suspicion that many EVA readers would ask me, if they weren’t so polite, a lot of these hard-hitting questions.

BUBBLE 3.0

An attractive young woman looks straight into the camera, with a slightly predatory look on her face.

“Hi, this is Betty Fast from SNBC with a unique segment to offer our viewers today. I’m interviewing David Hay, Chief Investment Officer of Evergreen Gavekal in Bellevue, Washington, who is in the process of writing a most unusual book.”

“The first very different aspect of the book is its title: “Bubble 3.0” with the provocative, almost inflammatory, sub-title of “How Central Banks Created the Next Financial Crisis”. The second highly unconventional angle is that he’s publishing it on the installment plan, running each new chapter he creates in his firm’s online newsletter, the Evergreen Virtual Adviser which goes by the acronym of EVA.”

“Apparently, Mr. Hay did foresee the bursting of both the tech and the housing bubble. While I couldn’t verify the first warning, he’s been writing his digital newsletter since 2005, so I was able to go into Evergreen’s archives and confirm that as early as 2006 he did, in fact, repeatedly warn his readers that there was a dangerous bubble in housing. Further, he did caution as early as the fall of 2007 that a recession was likely the following year. “

“However, to shatter any illusions that Mr. Hay has a crystal ball, he’s also been telling his readers for years that the US stock market is overvalued and that US economic conditions are not as healthy as they seem. Since my network is often derisively called “See No Bubble Communications”, with the implication that we have a persistently glass half-full view of the stock market, in the interest of objectivity, we wanted to take this opportunity to hear—and challenge—the half-empty viewpoint.”

“With that let’s now turn, literally, to Mr. David Hay.”

(Betty Fast turns to her left and the camera pulls back to reveal her guest.)

Betty Fast: “So, David, we’ve got record low unemployment, booming corporate earnings, a stock market that refuses to go down despite considerable geopolitical turmoil and a valuation on forward earnings for the S&P 500 that is a very reasonable 16 times? What’s not to like?”

David Hay: “Those are valid points. The huge question is if they are sustainable. The reality is that major stock market peaks are put in when unemployment is very low and corporate profits are high. And the market almost always looks cheap on forward earnings because Wall Street is a great extrapolating machine. It just looks at the profit trend—up or down—and predicts more of the same.”

Fast: “But Wall Street has stayed correctly bullish in recent years while you have been, to put it charitably, prematurely bearish.”

Hay: “Yes, you are being charitable, Betty. I’ve been worried that US stocks were in the danger-zone since at least 2014. As a result, I’ve been thinking of changing my middle name from Mills to “So Wrong, So Long.”

Fast: “Funny—sort of—but I’m not sure your clients see the humor in it.”

Hay: “Like Jimmy Buffett, Warren’s distant cousin, sings: ‘If we couldn’t laugh, we would all go insane’.”

Fast: “But bullish money managers and their clients have been laughing all the way to the bank while you’ve been hung up on things like debt levels, central bank policy mistakes, etc.”

Hay: “Ok, let’s home in on your ‘all the way to the bank’ comment. I think that’s how most investors feel – like they’ve literally banked all the gains of recent years and that no one can take those away from them. In my opinion, that’s a dangerous fallacy.”

Fast: “How so?”

Hay: “Just look at the last two bull markets. Years of profits were erased in the span of about one year after the housing boom went bust. It took longer when the tech bubble imploded but that agonizing two and half year bear market took the Nasdaq down almost 80% and wiped out the gains that investors thought they had ‘banked’ back to early 1996.”

Fast: “But that was then and this is now. No Wall Street strategist is anticipating any serious trouble. In fact, almost all of them have the S&P rising further this year and next. Why can’t this bull market continue to charge on for years—maybe another decade, as some are suggesting—further humiliating you and your fellow skeptics.”

Hay: “Sure, anything’s possible – particularly in this era of extreme central bank meddling in financial markets. But that would mean this bull would last about twice as long as the great bull market of the 1990s did—and we know how that ended. Like John Hussman says...”

Fast (groaning): “Oh, my God, does anyone listen to him anymore?”

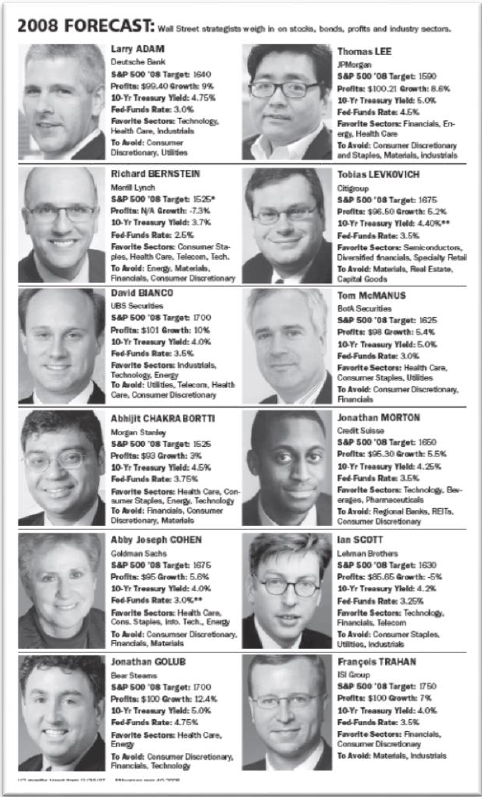

Hay: “He still called the last two bear markets so he deserves some credit for that, despite missing the 2009 bottom. He has a great line with a lot of truth in it. As a money manager, you are either going to look like a fool before the bubble pops or after. And I brought this little visual along just in case you brought up the idea that Wall Street will get their clients out before the next cataclysm.”

Source: Vincent Deluard, INTL FCStone Financial

Source: Vincent Deluard, INTL FCStone Financial

Fast: “Hmmm, so this looks like it’s from December, 2007.”

Hay: “Yes, and I know you can’t read all of it in a few seconds but, basically, none of the leading Wall Street strategists back then saw a bear market, much less the total collapse we actually suffered. A couple of them did see profits falling slightly, but even those two were calling for a flattish to slightly rising market. And this was after it was clear that housing was in a free fall and that it was already having a serious spillover into the economy—despite former Fed-head Ben Bernanke’s assurances that the problems were contained in sub-prime mortgages. My point is that if you are counting on Wall Street—or even the Fed--to give you a heads-up when the trap door is going to open up, you are going to be very disappointed…and wind up with a seriously stretched neck.”

Fast: “But, let’s face it, in recent years they’ve been right and you’ve been wrong. From reading your newsletters back in 2014 you thought the market was close to a peak and here we are up another 41%.”

Hay: “You’re right, it’s been both incredibly frustrating and embarrassing. However, if you go back and look at 2015, it was a much tougher year than was reflected by the S&P being up 1%. Many of the best managers on the planet—including Warren Buffett, Seth Klarman, Carl Icahn, and Mario Gabelli—had tough, to downright, awful years. A number were down in double-digits.”

Fast: “What about Evergreen? Did your conservative positioning help your clients avoid that year’s problems?”

Hay: “We certainly held up much better than the market during the big August sell off on the equity side of our portfolios but we did get hit with our energy investments, many of which were in our income portfolios. It was one of the worst bear markets ever for oil and gas securities, including the typically defensive master limited partnerships, or MLPs. But, most of our accounts had single digit declines.”

Fast: “So did you buy into the weakness back in 2015? I don’t recall reading that you became bullish on stocks.”

Hay: “You’re right again. The US stock market never corrected enough to get it down to what we felt were attractive valuations, though it got close—very briefly—in early 2016. On the other hand, energy equities, and a wide range of corporate bonds, were beaten down to extremely attractive prices, often offering double digit yields.”

Fast: “Yes, I did see you were repeatedly recommending those in your newsletter at the time.”

Hay: “We sure were, and we were also buying them for our clients. Because credit spreads were so high back then, a number of corporate bonds had returns of 50% over the last two-plus years. Some MLPs rallied by 200% or more, despite the fact they remain out-of-favor. The overall MLP index is up roughly 50% as well from the early 2016 lows when your network’s main personality was telling viewers to avoid them like an IRS audit.”

Fast: “So you are a contrarian, that’s quite obvious. But I have to wonder if you aren’t an endangered species these days given the increasing dominance of passive investing and algorithmic computer trading.”

Hay: “It certainly has been the perfect storm for those of us who like to buy when prices are low. We basically have been in a relentlessly rising market for almost 10 years with just a few short and shallow pull-backs. But we still believe markets are cyclical and the fact that we haven’t seen a down cycle in so long likely means it will be vicious when it finally shows.”

Fast: “We’ve been hearing that for a long-time from perma-bears such as yourself.”

Hay: “That’s not a fair label. Go back and read our newsletters during the worst of the 2008 and 2009 crash when we were emphatically telling our readers to buy almost everything as long as it wasn’t T-bills. But people were so scared back then it was hard to even get them to stick with income securities that were yielding over 10% in many cases. We went so far as to recommend junk bonds at yields over 20%. People thought we were nuts.”

Fast: “ But why did you see overvaluations as far back as 2014?”

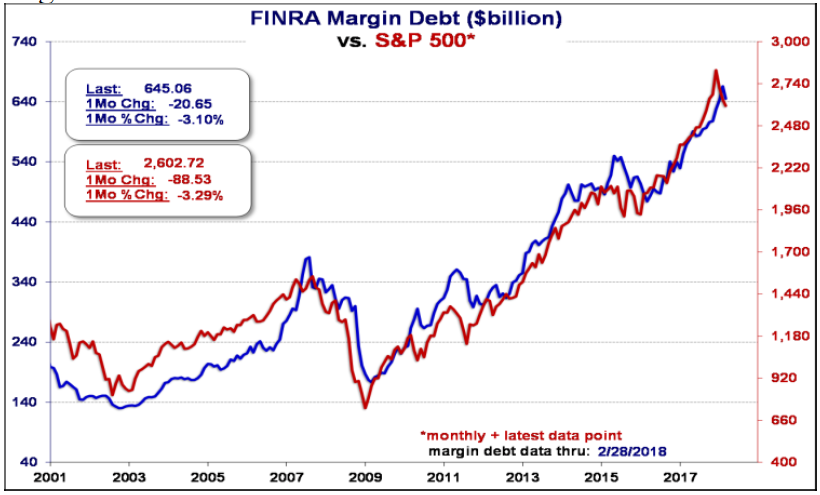

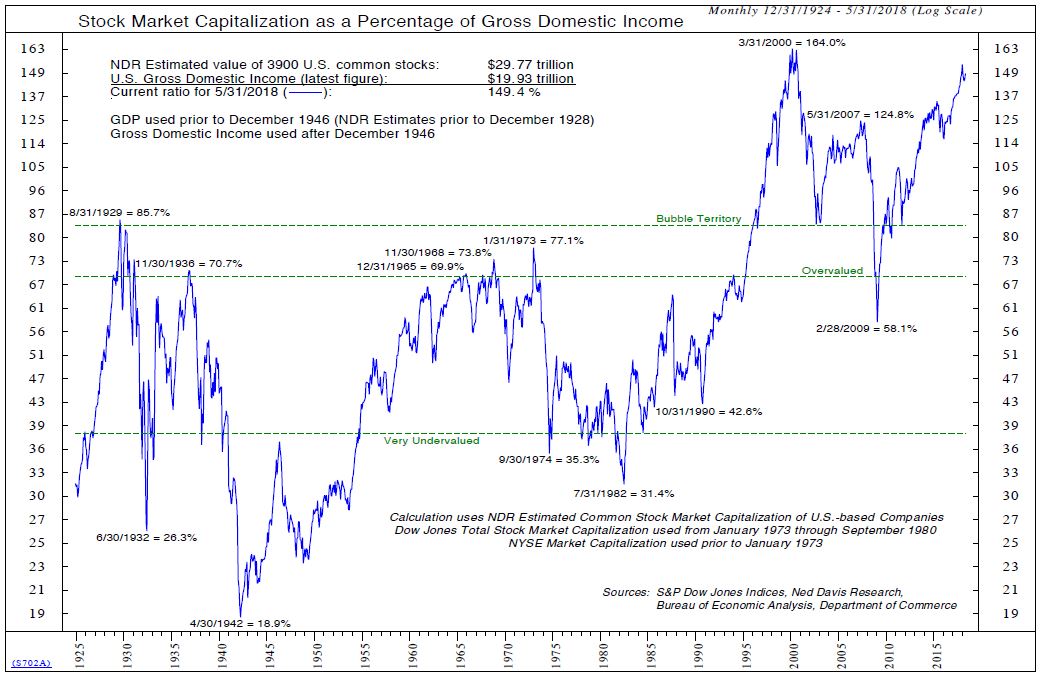

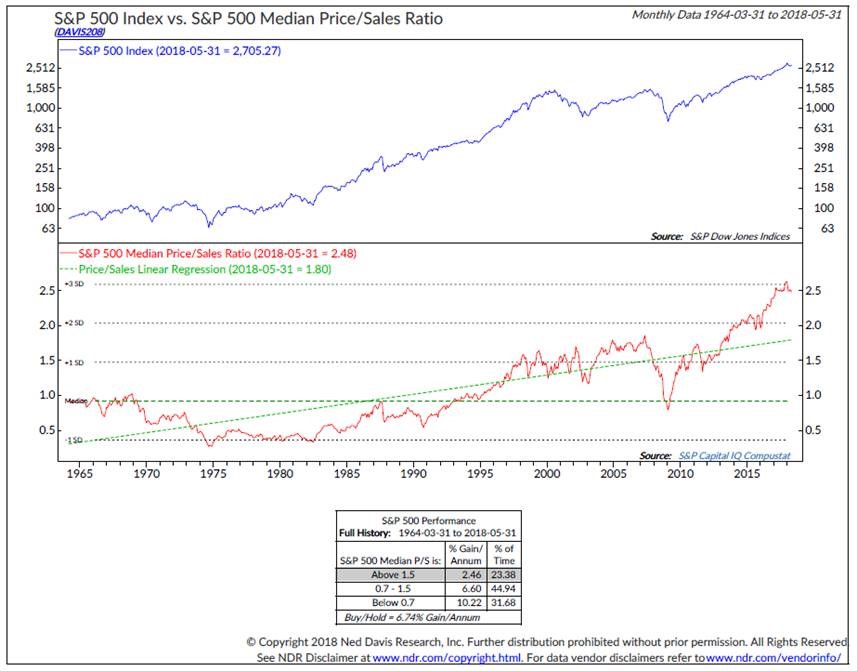

Hay: “Again, I’ve got a couple more visuals to show you and your viewers. Look at the level of margin debt back then as well as the median price-to-sale ratio and stock-market- value vs. gross domestic income. Some of these readings were even higher than they had been during the craziest days of the tech bubble.”

Source: Fred Hickey, The High-Tech Strategist

Source: Fred Hickey, The High-Tech Strategist

Source: Ned Davis Research

Source: Ned Davis Research

Source: Ned Davis Research

Source: Ned Davis Research

Fast: “Those looked worrisome at the time but…”

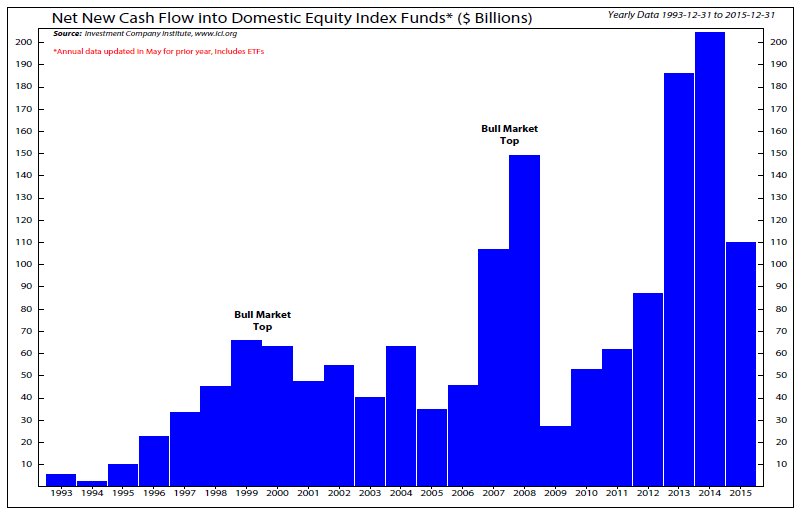

Hay: “But there’s more, look at the net flows of new cash into US stock index funds back then.”

Source: Ned Davis Research

Source: Ned Davis Research

Hay: “So, when we looked at all of this plus the likelihood that sky-high profit margins were going to come down, it led us to the conclusion that we needed to be unusually defensively positioned for our clients”

Fast: “But, instead, stocks and profits have continued to go straight up.”

Hay: “Well, actually, not so much. The S&P went through a six-quarter earnings recession in 2014 into early 2016.”

Fast: “And yet the market kept rising? Why do you think that was?”

Hay: “In hindsight, central banks.”

Fast: “But the Fed stopped its quantitative easing program in late 2014.”

Hay: “That’s true but other central banks revved up their printing presses into hyper-drive once the Fed stood down. Mid-last year was the peak in global QEs. As we’ve written several times, the Swiss National Bank has used the money it has created out of Matterhorn-thin air to directly buy US stocks. It is now one of the largest holders of US large cap tech companies and it’s done all that with money it just willed into existence courtesy of its digital printing presses. Do you think that’s healthy?”

Fast: “I’m supposed to be doing the asking, David, but in the old days, I probably would have said no. However, the fact is that what central banks have done has worked. We have a booming economy and a roaring, soaring stock market.”

Hay: “So, you’re bringing up a great point and I’m planning to devote an entire chapter of my book to that theme, titled: ‘What Price Prosperity?’ I mean, think about it…the Fed cut rates down to nothing and left them there for years. It bought around $4 trillion of bonds with fake money. The Federal government has doubled our national debt in 10 years. And what have we got to show for it? The weakest recovery in the post-World War II era.”

Fast: “But now we may see a 4% growth quarter, at least in the US.”

Hay: “True, we may and probably will, though the first quarter was just revised down to 2% which is where we’ve essentially been stuck for years. You can’t really look at one quarter and say that’s the trend. A lot of what’s happening now is a result of the tax deal and the stimulus that provided to consumers and businesses. But, again, at what long-term cost? The Federal deficit is almost certain to double this year. That means $500 billion more of debt that needs to be financed, for a total annual deficit of $1 trillion. That’s shocking during an economic expansion. And then there’s the Fed, the market’s ex-best friend.”

Fast: “What do you mean ex-?”

Hay: “Back before Trump, during Obama’s second term, earnings and growth were consistently disappointing. As I said, we actually had one-and-a-half years of falling corporate profits. Yet, the market went up and the mantra back then was ‘Don’t fight the Fed’—meaning, as long as it was easy, party on. Now though, it has hiked seven times and it is projecting five more by the end of next year. Plus, later this year the Fed is scheduled to be selling $60 billion a month of its government bond holdings. That will be a $720 billion annualized clip. So, we’ve got a collision of epic proportions between exploding government borrowing needs and the Fed’s huge sell-down. Then there’s the yield curve.”

Fast: “That’s certainly getting more attention these days. But the consensus view is that even if it inverts, it could be another eighteen months or so before that spells trouble.”

Hay: “That does seem to be the consensus view and it could be right but we’ve never before had a double-tightening.”

Fast: “What do you mean, a double-tightening?”

Hay: “A situation where the Fed is both raising rates and doing QT—quantitative tightening—the polar opposite of QE. We are in totally unchartered waters.”

Fast: “But you have to admit that this market has been unbelievably resilient. Maybe it can continue to climb despite this so-called double-tightening.”

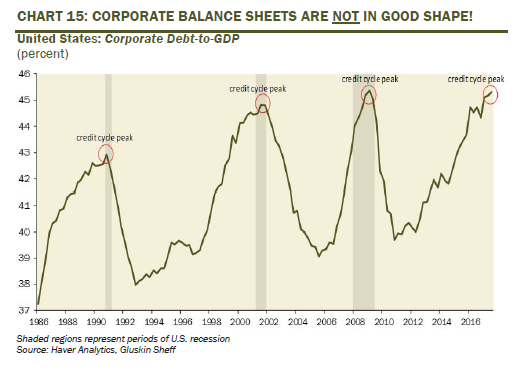

Hay: “Maybe, but let me broadly outline what I think has been the chain reaction that has continued to fuel this mighty bull market. First, rates went down to next-to-nothing making it almost painless to leverage up. Next, companies did just that so that Corporate America’s balance sheet now looks like this—another visual.”

Source: Haver Analytics, Gluskin Sheff

Source: Haver Analytics, Gluskin Sheff

Hay: “And rather than use the money to build new plants or buy new computers, publicly-traded companies have bought stock back in record-breaking amounts. As a result, capital spending has been in a long downtrend—with, admittedly, a decent pop lately—as has productivity. There’s no doubt cap ex and productivity are related, and the latter is absolutely essential for economic growth, particularly in aging society.”

Fast: “All of this has been an ongoing concern of the bears and the bull just keeps running.”

Hay: “Yes, it does but look at your parent company as a poster-child—or, more accurately, a red-headed step-child—for what this ultimately leads to.”

Fast (sighing): “Thanks, I’d rather not. Looking at my stock plan is depressing enough.”

Hay: “Exactly. And what has caused GE to be such a dog? It bought high and it sold low. Under its former CEO it bought a bunch of companies close to the peak of their cycle, at inflated prices. And then it sold many of them for losses. It also bought back a ton of stock in the twenties and now it’s in the low teens.”

Fast: “Don’t remind me. But what does that have to do with Corporate America overall?”

Hay: “First, when money is too cheap for too long, big companies tend to make a lot of bad deals, like GE overpaying for acquisitions. We won’t really know how harmful and pervasive this has been until the next recession when, I’m virtually certain, there will be a lot of GE-type confessionals. Globally, takeovers are running 65% higher this year versus last and 2017 was no slouch as far as deals went. Second, also like GE, most companies in recent years have been buying their own stock back at inflated prices. When the next economic downturn and bear market strikes, I believe you are going to be surprised how many will need to raise equity—at much lower prices—to shore up their balance sheets and prevent rating downgrades—just as GE is now doing. In essence, they are destroying trillions of shareholder wealth. But, of course, as the Wall Street Journal recently reported, insiders have been furiously exercising and selling their shares even as the companies they control are doing massive repurchases. When American’s see their 401ks vaporize—again—they are going to be furious over this situation.”

Fast: “So the chain reaction you described is that low rates lead to high leverage as companies borrow to buy their own shares back at increasingly stretched prices and that long-term investment in R&D and equipment suffers. Is that it?”

Hay: “Not quite. There’s also the role of passive investing in this process.”

Fast: “How so?”

Hay: “Index vehicles like ETFs are perfect for bull markets, especially those that go up as continuously as this one has. Most ETFs hold no cash and they are most heavily exposed to the largest companies. As immense sums of money come into them—from all those boomers in need of higher returns—the largest amounts are channeled into the biggest market value companies…by definition. There is no thinking involved, no analysis of intrinsic value. As long as the money is flowing in, this is a self-perpetuating cycle and it all works great as long as prices are rising. The problem is what happens when they fall and history is clear that when you get as high as we are now, with as much leverage as there is around presently, markets don’t just have soft-landings—they tend to be much more of the crash-variety.”

Fast: “But once again you’ve been saying this for a long time. When does it end, when should investors get out?

Hay (chuckling ruefully): “Whenever people ask me when, I say three years ago. 2015 really looked like the pieces were falling in place for a 2008 type event.”

Fast: “So what happened?”

Hay: “First, it was the aforementioned QE-to-the-max efforts of foreign central banks. Second, along came Trump. As I’ve written to my readers, love him or loathe him, his election changed everything. Investor and business confidence soared as soon as it became clear he won the electoral vote. The euphoric response was just the opposite of what was expected and it also extended internationally, which is pretty ironic given the low esteem he’s held in overseas. The US economy and our stock market were looking winded back in late 2016 but there’s no doubt Trump’s election gave the bull market a new lease on life.”

Fast: “Justifiably.”

Hay: “In some ways, yes. He’s certainly brought a very different tone to the White House toward the business community. And’s he’s done a decent amount of regulatory roll-back, something that was greatly needed. Corporate America loved his tax deal, of course, but I’m much less of a fan.”

Fast: “Why?”

Hay: “First, there’s very little simplification – though for the middle class there might be a decent amount and that’s great. But for those of us with more complex returns, the filing process is still excruciating. But the worst part is what it does to the deficit as we discussed. Government borrowing costs are already up 15% year-over-year and with the entitlement spending blow-out for boomers like me approaching, that number is certain to continue doing a moonshot. Further, Fed rate hikes are necessary but are going to only make it worse. If you think that I’m being too pessimistic consider that by 2041 the entire Federal budget will be consumed by interest payments, healthcare expenditures, and social security. That’s according to the Congressional Budget Office, not me. And they don’t assume a recession anytime along the way which is absurd. For a terrific overview of the budgetary nightmare the government is facing, I’d suggest your viewers go to John Mauldin’s website and read his June 30th issue of Thoughts from the Frontline.

Fast: “But those budget threats are long-term and our viewers are much more concerned about what the stock market is going to do over the next few weeks or months.”

Hay (chuckling sardonically): “No doubt and that’s a big part of the problem. No one wants to think about the long-term. We’ve become a nation of trend-followers.”

Fast: “It is what it is. Now, a recession could be a different story. You were one of first and few to see the last one coming. Do you see a downturn looming?”

Hay: “Well, not in your viewers’ timeframe of a few months. But the back half of 2019 looks like much more of a possibility.”

Fast: “Why?”

Hay: “First, the yield curve. The difference between 2-year treasuries and the 10-year T-note is already down to a crepe-like level of 30 basis points, or under 3/8% in English. With five more rate hikes scheduled, the curve is almost certain to invert.”

Fast: “Why almost? With the Fed saying it is going up another one and a quarter percent, isn’t that a certainty?”

Hay: “First, there is a distinct risk that we get a scary- high inflation number in the next few months. There is a lot of inflationary pressure building, especially in wages. A bad inflation print could easily send the 10-year yield up close to 4% in a hurry, temporarily steepening the yield curve.”

Fast: “Why temporarily?”

Hay: “Because with all the debt the world has taken on—$70 trillion over the last dozen years or so—my firm believes the system can’t tolerate rates that high. We are already seeing stresses appear for both autos and housing in the US. Plus, anything close to 4% on the 10-year is likely to create serious problem for overleveraged companies and may well trigger the next financial panic. If so, the 10-year yield will plunge perhaps below 2%, creating a severely inverted yield curve if the Fed has hiked even two more times by then. If it happens sooner, then maybe the curve just slightly inverts. Should the 10-year stay where it is now, the odds are very high the curve will invert sometime in the first half of next year. That’s always problematic.”

Fast: “We’re running out of time so how would you summarize your outlook.”

Hay: “Frankly, I think the biggest delusion out there, including at the Fed, is that asset bubbles haven’t happened yet and that leverage is not excessive. Jay Powell, who I think has the makings of a great Fed chairman, just said words to that effect. With all due respect to Mr. Powell, we’ve had margin debt as a percentage of GDP at 3% for over four years. That’s never happened before. It got up around there briefly in early 2000 and again in 2007, precipitating big crashes shortly thereafter. As we saw, corporate balance sheets have never been more leveraged. The government is drowning in debt with a tsunami of red ink on the horizon. I mean, come on. We have interest rates at 5,000-year lows and they’ve been down here for a long, long time. How could we not have bubbles all over the place and especially in the three main asset classes of stocks, bonds, and real estate? Look at what happened with Bitcoin and the rest of the cryptos—those were the biggest bubbles in recorded history and I think the signature boom/bust of this cycle—with many more explosive deflations coming to an asset class near you soon.”

Fast: “Sorry, I just have to ask, isn’t there any way this can end well – in some kind of soft-landing?”

Hay: “That seems highly improbable, what I call the ‘Immaculate Correction’ scenario. I am planning, though, to write a chapter in ‘Bubble 3.0’ called ‘What Could Go Right’—if things haven’t blown up before I do. But, look Betty, America is still the most dynamic country on the face of the Earth. We’ll eventually institute sound policies again and there’s another boom up ahead based on robotics, AI, US energy abundance, gene-editing, 3D-printing, and a host of other positives. It’s just that getting from here to there isn’t likely to be pretty.”

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

* Credit spreads are the difference between non-government bond interest rates and treasury yields.

** Due to recent weakness, certain BB issues look attractive.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.