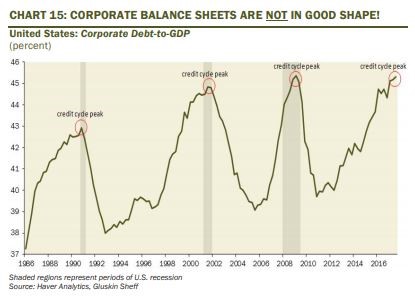

“This time around, the big bubble is the extreme leverage on the corporate balance sheet, where the chart of debt-to-GDP looks a lot like the mortgage debt-to-GDP in 2007.”

–DAVID ROSENBERG, one of North America’s most influential economists

“If 2008 taught us anything, it is the importance of being vigilant when times are still good.”

–Leading consulting firm MCKINSEY AND CO.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

At the beginning of 2018, we initiated a new EVA series titled “Bubble 3.0” with excerpts from my upcoming book (tentatively titled “Bubble 3.0: How Central Banks Created the Next Financial Crisis”).

If you are just joining us in the middle of this ongoing series, which will eventually culminate in a full-length publication (hopefully not before the expanding “Biggest Bubble Ever” or “BBE” bursts), please take a few moments to review the prior installments in the series:

Since our last issue, there have been important changes in some key markets both in the US and around the world. Please read on to learn more…

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

CHAPTER 5: The Biggest Bubble Inside the Biggest Bubble Ever

Are US stocks more overvalued than at any other time except 1929 or 1999? Or are they even more expensive? Or are they reasonably priced, as so many media commentators and Wall Street strategists contend? The answer sort of reminds me of the old story of various people applying to be hired as an accountant at a certain firm. The owner asks each applicant what two plus two equals. The first dozen or so give the obvious reply and the boss politely but quickly dismisses them. Finally, one cagey interviewee—who clearly shows the mindset to be the CFO of a publicly traded corporation—answers: “Whatever you want it to be.” Of course, this person got the job.

Depending on which methodology you use—median price-to-sales ratio, total stock market value vs GDP (adjusted for overseas sales), enterprise value (equity market capitalization plus debt) compared to cash flow (EBITDA), or P/E based on next year’s (hoped for) earnings—you can come up with whatever answer you want. Debating this with true believers in their preferred metric, is nearly akin to arguing the articles of faith with an ardent Jew, Christian, Muslim or Buddhist. (Wait a second, do Buddhists argue?)

In this edition/chapter of our Bubble 3.0 EVA series, I’m going to tread on much safer ground. Instead of tackling the great stock valuation debate, my focus is on a market that, frankly, most investors ignore, the one that is made up of those sleepy instruments known as bonds.

But just because bonds are off the radar of the majority of market participants doesn’t mean they aren’t important. The fact alone that central banks have pumped nearly all of the $11 trillion they’ve digitally fabricated into fixed-income securities is proof-positive of their importance. Or looking at it a bit differently, while not many people care about bonds per se, almost everyone cares a lot about interest rates.

Fixed-income 101 tells us that bond prices and interest rates move inversely. That is, when a bond’s market value increases, its yield decreases. When yields fall in a big way, the returns can be surprisingly equity-like. For example, the below issue, for mid-stream energy titan Enterprise Products, produced a 20% per year return if purchased close to its 2016 low over the past 2 and ½ years.

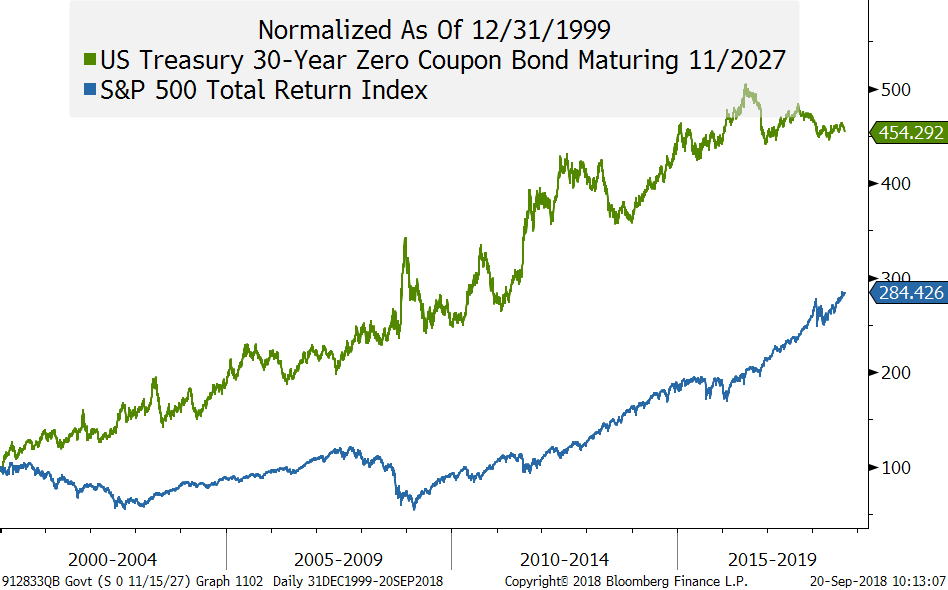

Similarly, I doubt most gung-ho stock investors (isn’t that almost everyone these days?) are aware of the below total return comparison between 30-year zero-coupon treasury bond and the S&P since the dawn of this century/millennium.

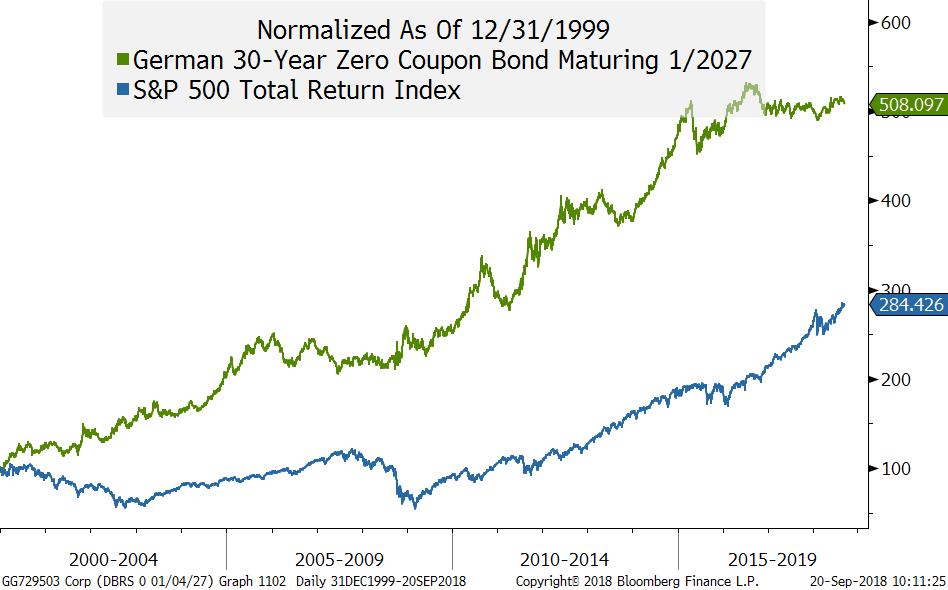

Or, let’s get even more extreme and look at the return in US dollars on a long-term German government bond (known as a “bund”) and the supposedly nearly-impossible-to-equal, much less beat, S&P 500.

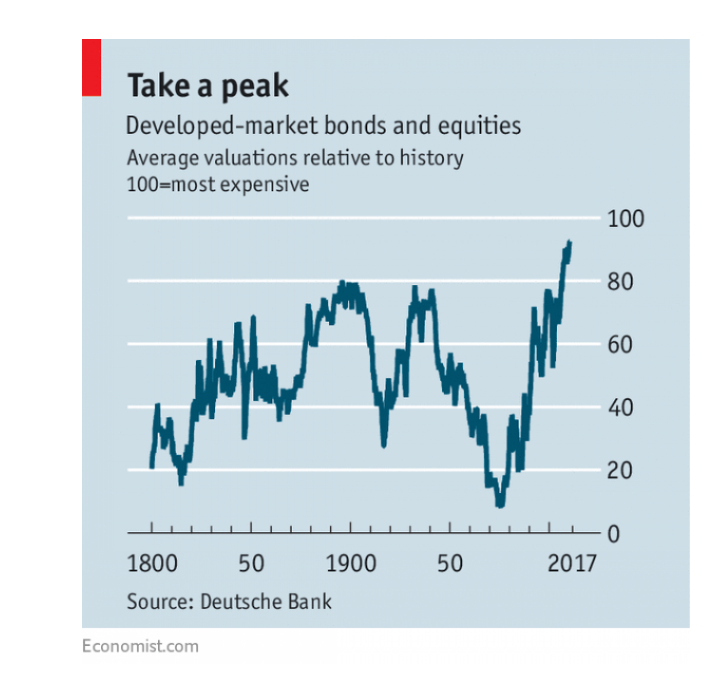

Let the protests begin! The sound of all the equity cultists vociferously objecting is already ringing in my ears. Of course, they say, what do you expect? Central banks have ridiculously and massively distorted almost all major bond markets. And you know what? They’re absolutely right. $11 trillion of binge printing by the planet’s monetary mandarins couldn’t help but have an impact. In fact, even though interest rates have been rising around the world this year, there are still nearly $8 trillion of bonds that “sport” negative yields (which, to my mind, is anything but sporty).

It is incredible that nearly a decade past the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the world remains heavily populated with bonds which investors pay the borrower for the “privilege” of investing. Even in the US, which, thanks to seven Fed rate hikes, is the highest-yielding bond market in the developed world, interest rates are at levels that in pre-crisis days would have been considered recession-level.

As a result, it’s hard to argue that bonds haven’t been, and basically still are, caught up in the biggest bubble in recorded human history. The only time they’ve been lower was back in 2016 before the Fed started tightening and in the wake of Brexit which drove the US 10-year T-note yield down to 1.3%. At that point, US interest rates were below anything seen during the worst of the worst hard times—as in the Great Depression. In the rest of the “rich” world, that was even more the case—and still is.

Think about it for a moment. In 2016, seven years into a recovery from the crisis, the developed world was still relying on bond yields lower than those experienced during the 1930s when economic activity totally collapsed—leading to the rise of fascism and communism—in order to…well, that’s not a simple point.

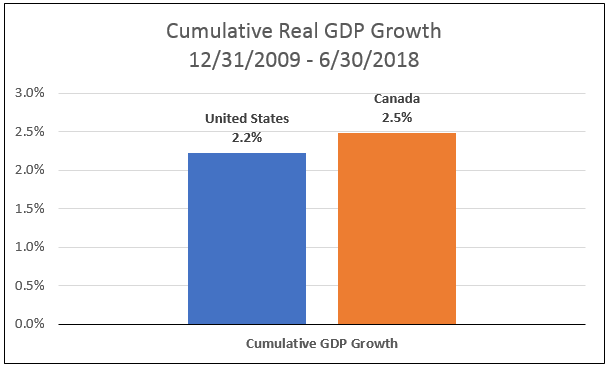

Was this totally unparalleled stimulus meant to create economic growth? If so, the results were disappointing, even in the US. As many prior EVAs have observed—and it’s simply a fact, not an opinion--this has been the worst recovery in post-WWII history. Most overseas advanced economies have been even worse. It’s interesting to note that the only one that has not resorted to the quantitative easing (QE) remedy is also the only one that has outperformed the US, our good neighbor to the north.

Or was this extraordinary, unprecedented monetary manipulation intended to raise inflation to the 2% level with which central bankers today are so obsessed? Putting aside the question as to why it is desirable to erode a currency’s purchasing power by 40% over 25 years—which is what 2% inflation produces in that length of time—is it worth expending trillions to move the CPI up by, say, ½%.?

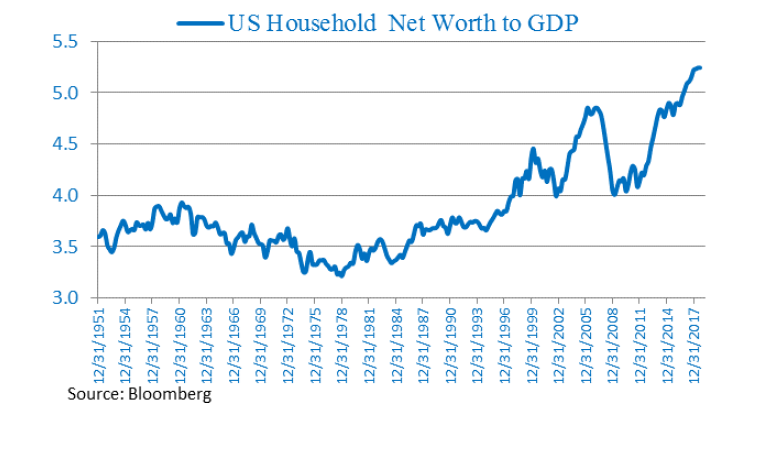

Or, was it the goal of central banks to drive asset prices to extreme (some, like me, would say bubble) levels in order to create a wealth effect, thereby turbocharging economic growth? If so, and former Fed head Ben Bernanke plainly stated years ago that was the goal, have they succeeded?

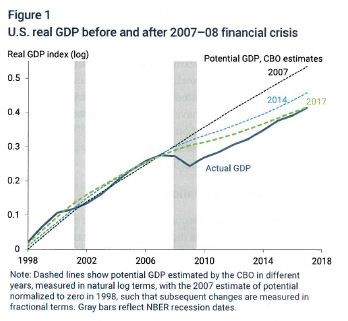

Per the above comment about the reality of how deficient this expansion has been, it’s hard to argue that the Fed succeeded on economic grounds. (The sorry chart below is from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco!) The results of nearly all other developed countries were even worse.

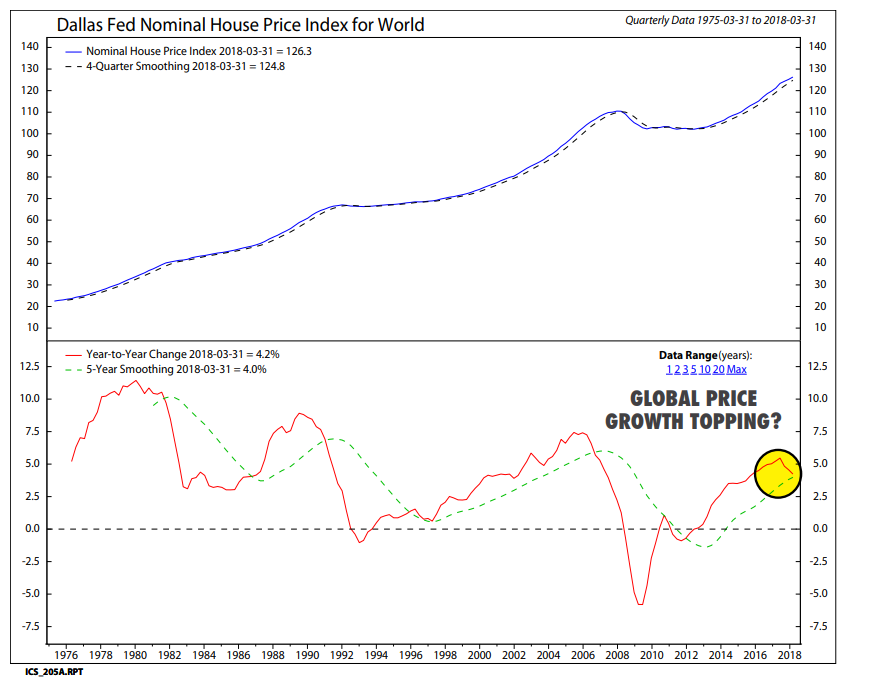

But when it comes to asset prices, the tsunami of trillions and the related collapse in interest rates, has swamped all those (like me) who dared to question the wisdom of incessant QEs. At least that was the case until fairly recently when a number of important markets have come under stress, including the once-thermonuclear hot Seattle-area housing market. We’ve previously run a multitude of charts showing how expensive US stocks and most real estate around the world have become in recent years. Yet, as long as they continue to levitate, and even float higher, such visuals are dismissed as irrelevant or sour grapes on the part of those of us who keep running them. (Actually, right now, it’s pretty much only the S&P 500, led by a handful of stocks and, bizarrely, the small cap Russell 2000 that are still rising; more on the latter in a future “Bubble 3.0” chapter.)

Moreover, the relaxed attitude by US investors toward the carnage in overseas markets this year and the increasingly obvious problems in global real estate borders on the reckless. It’s almost as if as long as the S&P 500 continues to rise, the American investor class could not care less about erupting Federal deficits, falling home prices (in Seattle, they just fell by 6% in one month!), and serious trouble in foreign stock, bond, and currency markets. But I digress…

Returning to interest rates, this chapter’s main theme, last week a perceptive Evergreen client sent me an excellent article by columnist Edward Chancellor, titled “The Mother of All Speculative Bubbles”. (Sure sounds like a great fit with a Bubble 3.0 EVA, doesn’t it?) In the opening section, he gets right to the heart of the matter by quoting the father of economics, Adam Smith, on the impact of interest rates on property prices a few years ago—like back in the 1700s!

In 1776, English man of letters Horace Walpole observed a “rage of building everywhere”. At the time, the yield on English government bonds, known as Consols, had fallen sharply and mortgages could be had at 3.5 percent. In the “Wealth of Nations”, published that year, Adam Smith observed that the recent decline in interest rates had pushed up land prices: “When interest was at ten percent, land was commonly sold for ten or twelve years’ purchase. As the interest rate sunk to six, five and four percent, the purchase of land rose to twenty, five-and-twenty, and thirty years’ purchase.” [i.e. the yield on land fell from 10 percent to 3.3 percent].

Smith explains why: “the ordinary price of land ... depends everywhere upon the ordinary market rate of interest.” That’s because the interest rate discounts and places a capital value on future income. All the great speculative bubbles in the past – from the tulip mania of the 1630s through to the global credit bonanza of the last decade, have occurred at times when interest rates were abnormally low.

The basic point is that as interest rates plunge to very low levels, buyers are willing to pay higher and higher prices for income-producing real estate. (When Adam Smith used the term “purchase” he was referring to annual cash flow.) Admittedly, that’s not a brilliant insight for real estate-savvy individuals but what seems to be forgotten is that there’s a lot of floating-rate mortgage debt out there and the cost of that in the US is rising fast. Perhaps that’s why—in addition to stupid-high prices—the Seattle housing market is starting to fade like one of our fair city’s sports teams at the end of its particular season (the local WNBA franchise being a notable exception; as usual, the Seattle Mariners are not).

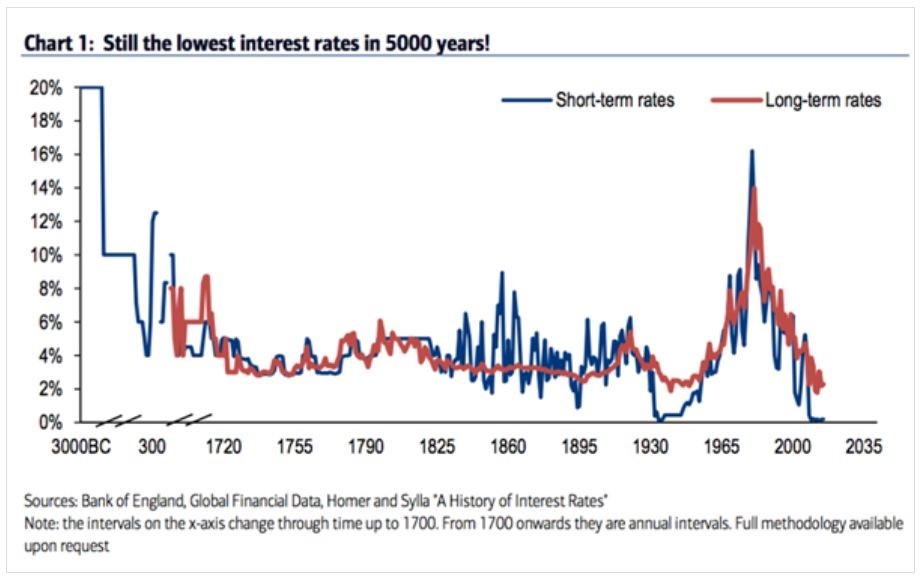

Another key point that Mr. Chancellor makes is that all monster bubbles are a function of low interest rates (to access the full article, please click here). In fact, I’d argue that’s not just a key point, it is THE key point, and not only of his article but of my book. If one accepts the reality (and not to is denying same) that recent years have seen the lowest interest rates in 5000 years, then how could we not be at least going through a massive bubble, if not, as I’ve contended, the Biggest Bubble Ever?

On that score, might there be more than just a casual connection between the charts shown below? Or is it actually more like a causal connection?

Still the Lowest Interest Rates in 5000 years!

In Chapter 2 of this Bubble 3.0 EVA series, we looked at housing and interest rates in Sweden. While acknowledging it isn’t the most systemically critical country on the planet, it is nonetheless an interesting (sorry) case study in what insanely low bond yields can cause.

First, for those of you who don’t waste your life studying these things like I do, Sweden had a whopper housing bubble in the early 1990s. And like ALL bubbles ultimately do, it popped—big time. The implosion was so cataclysmic that it wiped out the staid nation’s banking system. Additionally, as is nearly always the case, it triggered a severe recession.

One might think that such an experience would cause Swedish policymakers to do everything in their power to prevent a repeat performance. But, then again, one would also think the brainiacs at America’s Federal Reserve would be extremely bubble-averse after what happened from 2000 to 2002 and then again in 2008. In both cases, one should actually conclude: (Though, per this EVA’s conclusion, the Fed is presently undergoing an epic epiphany.)

In Sweden’s case, it was the world’s fastest growing developed country in 2015, with real growth cresting at 5%. Yet, in its central bank’s infinite wisdom, its official interest rate was MINUS 0.5% and, as predictably as #MeToo will soon claim another Hollywood mogul, Swedish home prices did a moon shot.

As you can see below, Sweden has made the top ten of riskiest housing markets with an estimated 165% overvaluation. This list also gives you the sense of the global nature of the latest housing bubble. The US didn’t even make the top ten despite the outrageous pricing in cities like Seattle, San Francisco, LA, New York and Washington, DC.

But something important has happened since Chapter 2 of the Bubble 3.0 EVA discussing the latest Swedish housing mania.Despite interest rates that remain absurdly low, Swedish home prices are falling. Starting in April of last year, flat (i.e, condo) prices in Stockholm slid by 9% and have continued declining throughout 2018. One of Sweden’s largest developers has been slashing prices 15% to 20% in its main Stockholm projects. Home prices in one of Stockholm’s wealthiest suburbs fell 17% this year through July. Now, if that were the stock market it would be no big deal. But drops of this magnitude in housing values is most unusual—like Seattle-area prices declining 6% in one month.

In Australia, prices have fallen for 11 straight months. Aussie banks are beginning to buckle and new revelations about imprudent and even illegal lending practices by major financial institutions Down Under are coming to light on a regular basis.

Canada’s bubbly property market has also come off the boil. Prices are apparently not yet falling (though there are some anecdotal reports this) but the Canadian MLS Home Price index is running at just plus 2.5% year-over-year versus a 20% annual rate of increase in April, 2017.

In the formerly ripping Manhattan housing market, the median price per square foot is 18% lower than a year ago. Accordingly, a major tide shift appears to be underway in global residential property markets.

Returning to Evergreen’s home turf, it’s not just housing prices that are headed in a southerly direction. Apartment rents are also down nearly 10%, the sharpest contraction of any of America’s biggest 100 cities. You can bet that with rates rising (forcing cap rates up) and rents falling, apartment values are as well…or will soon do so.

The big problem when real estate prices start tumbling after many years of lofty increases is the debt involved. This is especially the case in the US where first-time buyers on average put down just 7% of the purchase price, with VA- and FHA-backed loans often more like 3%. In other words, it doesn’t take much in the way of a price erosion to wipe out the equity of many of those who bought at or near the peak. Naturally, this makes lenders nervous which, in turn, makes them reluctant to extend new credit. The response is typically to tighten lending standards which could be quite a shock to the system after years and years of lax credit terms. (How in the world did we ever get back to 3% and 7% down payments?)

Moving beyond real estate, and the accumulating evidence that depreciation thereof is becoming much more than just a bookkeeping entry, let’s talk corporate debt. The news there isn’t all bad. In fact, some of it is encouraging, with a bit of fraying around the edges.

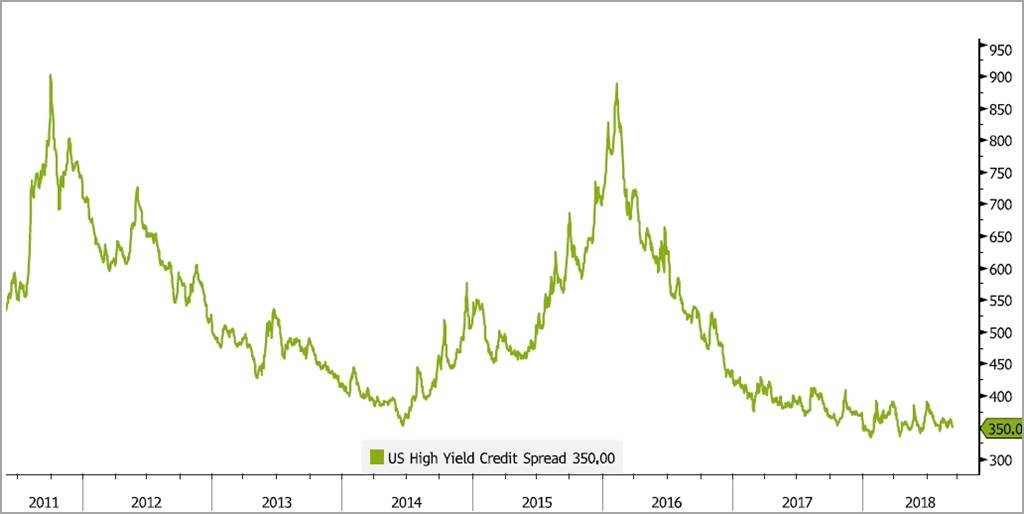

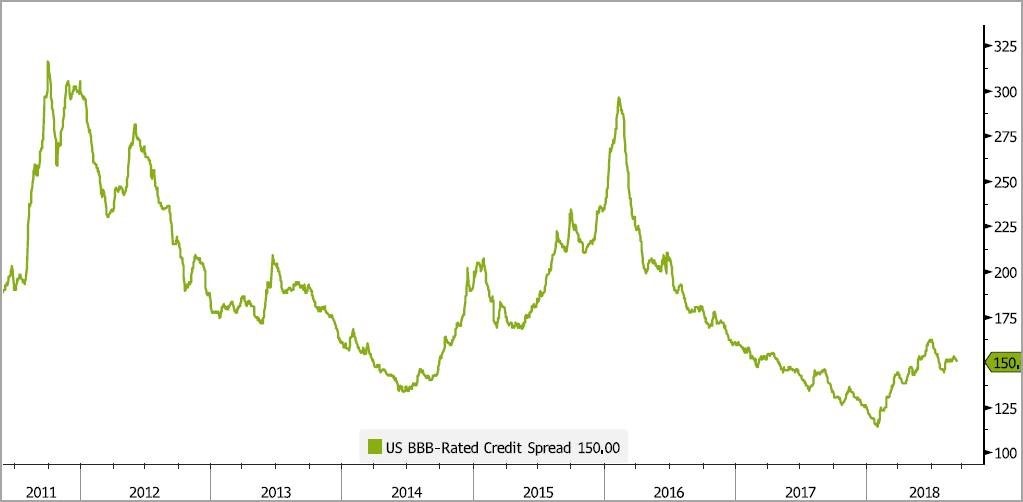

The least alarming aspect is that credit spreads (the gap between government and corporate borrowing costs) remain unusually narrow. This is especially true comparing the yields of US treasuries and junk bonds. Where there is some degradation is in the ultra-critical BBB-rated corporate bond category.

Junk Bond Credit Spreads (2011-Present)

BBB Credit Spreads (2011-Present)

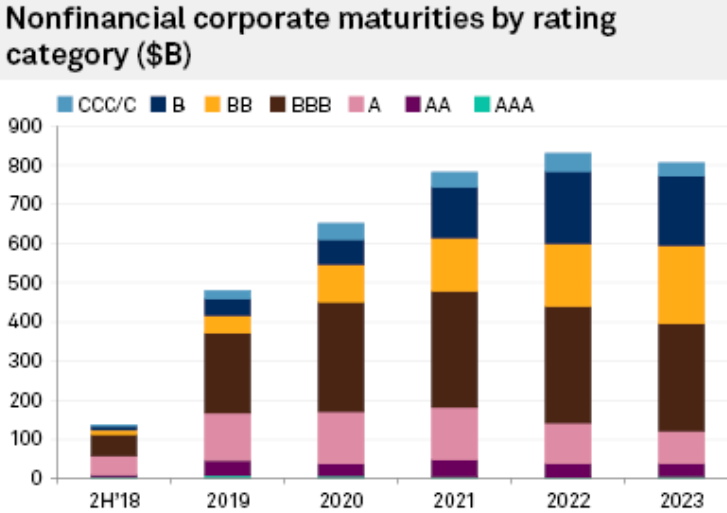

Part of the reason that the BBB space is of vital importance is that it is now as densely populated as downtown Manhattan. In fact, nearly half of all corporate debt is presently rated BBB. Many, if not most, of these issuers are household names and, at least formerly, considered to be blue chip enterprises.

But, thanks to the irresistible allure of being able to borrow at almost nothing, until lately, as well as the equally captivating charms of the wonderful management enrichment scheme of multi-trillion dollar share buybacks, corporate America no longer boasts a collective fortress balance sheet. In fact, the Barbarians at the gates are climbing the parapets on a mounting pile of debt.

Up until now, it’s been a non-issue and, frankly, for most companies that remains the case. Miniscule borrowing costs have made this towering wall of debt easily financeable. This is particularly true for those prudent entities that have extended their liability maturities. According to Barron’s, there is $8 trillion of US corporate debt coming due over the next two years.

For those entities that are relying on floating rate financing and/or are facing a sudden spike in maturing debt, the situation may soon become seriously precarious.

There is also the reality that one of the worst times to be an investor in lower-rated corporate bonds, or even mid-tier quality, is when credit spreads are low and begin to rise. As prior EVAs have observed, it’s looking probable that BBB credit spreads are in a persistent up-trend having clearly broken their downtrend since the 2016 peak.

As we’ve also previously noted, rapidly declining (aka, narrowing) credit spreads are like mixing Red Bull with a double espresso when it comes to hyper-stimulating a bull market. The reverse is also true but it tends to happen with a lag. However, not all market air-pockets have been caused by a spike in credit spreads. The Crash of 1987 occurred despite narrowing credit spreads (and a very strong economy, far more robust than today’s). Like today, it was a time when complex trading strategies were all the rage, the Fed was on the warpath, and investors were jubilant.

For now, the rise in BBB credit spreads is just a case of the barometric measure easing but certainly not plunging as if a storm was looming right over the horizon. But it definitely bears monitoring—even if you’re not a bear. This is especially prudent considering that, also quoting David Rosenberg, half of US corporations are now rated just one notch above junk and 30% already have credit metrics that warrant a junk rating. Moreover, one-quarter of emerging market debt is at risk of defaulting based on its current status.

Quoting a retired senior rating agency insider, courtesy of my friend Danielle DiMartino Booth: “For the time being, the (debt) markets are so hungry for paper, they’ll buy anything. But when the next downturn arrives, we will quickly have a huge liquidity problem on our hands.” The below chart indicates this individual is not being an unfounded alarmist.

Underscoring the sheer magnitude of the increase in corporate debt leverage, globally it has increased by almost 80% over the last decade to $66 trillion, or about a $30 trillion leap. A hugely significant question is if corporate debt servicing capabilities have improved by anything close to this degree. We strongly suspect the answer is nyet (which doesn’t mean “not yet” in Russian but much more like “no way, Sergei!”.) The fact that a record 37% of US companies have debt that is five times their gross cash flow (EBiTDA) would seem to justify our skeptical view (for BBB-rated companies the debt-to-cash flow ratio is now 3.2 times versus 2:1 in 2007 on the eve of the credit crisis).

Finally, the increasingly popular Collateralized Loan Obligation (CLO) market is almost a carbon copy (yes, I know I’m dating myself, perhaps carbon-dating myself ) of the Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO) space that nearly destroyed the planet’s financial system ten years ago. Rapidly rising short-term interest rates on these, due to all of the Fed hikes, are nice for the lender but agonizing for the borrower. And borrowers who can’t pay their debt service eventually share the pain with their lenders.

Putting all of this together, I agree with those who suspect that one of the most probable causes of the next crisis will be corporate debt. (This is a key reason why Evergreen has positioned its clients’ bond and income portfolios heavily in cash equivalents.)

The bubble in bonds around the world and the related disappearance of interest rates is, of course, a massive problem for pension plans. There is such a large body of commentary on this topic that I’m going to cover it very briefly (for those that want to see financial newsletter giant John Mauldin’s take on this, please click here.

The basic problem is that nearly all retirement plan assumptions are far too high given both the low level of bond yields (including in the US) and the over-priced S&P 500. (There I go venturing into the stock valuation argument; therefore, I’ll just say even the Fed is now admitting stocks are so expensive that they’ll likely have a zero real return over the next decade.) Due to this reality—again, inarguable on the bond side of the equation—retirement plans are stretching for return…likely in all the wrong places, at least at this point in the cycle.

Pension administrators are plowing into private equity, real estate, and, yes, CLOs. The one thing most of these have in common is that they borrow short-term to lend or invest long-term. This is another repeat of a technique that blew up in spectacular fashion ten years ago, the carry-trade. It works wonderfully when rates are low on short-term borrowings and asset prices are levitating. But when rates rise briskly and, suddenly, prices start de-levitating, it’s not long before another “de” begins happening, as in deleveraging.

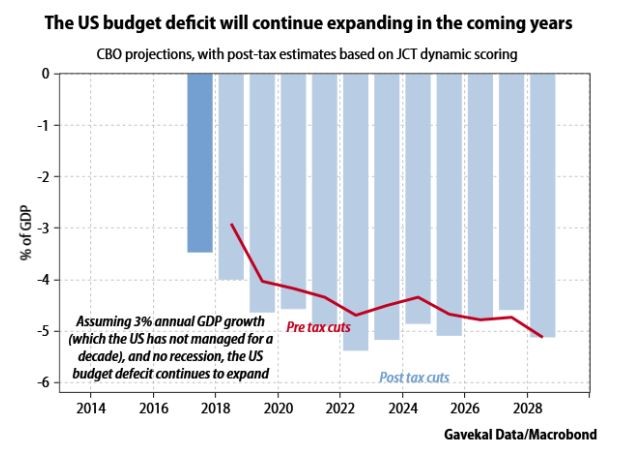

Finally, I would be remiss in not mentioning the impact of having interest rates so low, for so long, has done to government deficits. Inarguably, they have gone postal. Specifically, global sovereign debt has doubled to $60 trillion. This has also been the case in the US and, sadly, our fiscal fiasco is worsening, not improving as it should be at this stage of an economic up-cycle. More sadly yet, this deluge of red ink is set to continue per the chart below—even assuming 3% growth and, most improbably, no recession over the next decade.

Clearly, the bubble in bonds has led governments to conclude that doubling their collective IOUs in 10 years--versus what previously took a century or two--is a no-worries situation. Yet, there are a few voices, including hedge fund titan Ray Dalio, who are pointing out the limitations this puts on policymakers when another recession hits. It’s tough to open the fiscal floodgate during the next economic drought after you’ve depleted the reservoir when times were good.

To conclude this chapter of Bubble 3.0, until recently the Fed seemed to have kidded itself into believing that it had not yet allowed asset prices to rise into the zany zone. New Fed chief Jay Powell opined not long ago: “Today I see US financial stability vulnerabilities as moderate…While some asset prices are high by historical standards, I do not see broad signs of excessive borrowing or leverage.”

Very lately, though, there has been a radical tone shift. We are seeing an increasing amount of commentary from the Fed along the lines of this excerpt from one of its recent reports: “The Federal Reserve’s assessment suggests that financial vulnerabilities are building, which might be expected after a long period of economic expansion and very low interest rates." It gets better: “Rising risks are notable in the corporate sector, where low spreads and loosening credit terms are mirrored by rising indebtedness among corporations that could be vulnerable to downgrades…Leveraged lending is again on the rise..and the (Fed’s Survey on Bank Lending Practices) suggests that underwriting standards for leveraged loans may be declining to levels not seen since 2005.”

Wow, I couldn’t have said it better myself! This is remarkably—and uncharacteristically---clear language from an institution that used to pride itself on obfuscation. Consider yourself duly warned.

Perhaps the Fed is noticing the growing list of asset classes that are breaking down, save, of course, for the S&P 500. But when that goes—as eventually it must—it will be too late to rush the fire exits. The doors will be shut and the smoke will be lethal. As fun and never-ending as this bull market’s final act has been, you might want to discreetly sneak out...while the sneaking’s good.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

Changes highlighted in bold.

LIKE *

* Some EVA readers have questioned why Evergreen has as many ‘Likes’ as it does in light of our concerns about severe overvaluation in most US stocks and growing evidence that Bubble 3.0 is deflating. Consequently, it’s important to point out that Evergreen has most of its clients at about one-half of their equity target.

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

* Credit spreads are the difference between non-government bond interest rates and treasury yields.

** Due to recent weakness, certain BB issues look attractive.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.