“The ‘New Normal’ is not an environment of slower economic growth, it is one of perpetually accommodative monetary policy. To his credit, Jay Powell is trying to drain the punch bowl, but it is the size of a bathtub and he is using a straw…One thing that is longer than the longest bull market is the era of accommodative policy that fueled it.”

–Jones Trading’s chief strategist MIKE O’ROURKE

At the beginning of 2018, we initiated a new EVA series titled “Bubble 3.0” with excerpts from my upcoming book (tentatively titled “Bubble 3.0: How Central Banks Created the Next Financial Crisis”).

If you are just joining us in the middle of this ongoing series, which will eventually culminate in a full-length publication (hopefully not before the expanding “Biggest Bubble Ever” or “BBE” bursts), please take a few moments to review the prior installments in the series:

In our last “Bubble 3.0” installment, we took a slight detour away from our regular format to present a faux “interview” with a fictional talking head. This month, we will return to a more familiar style by presenting the fourth chapter in my work-in-progress book. As the title suggests, “Up from the Ashes” recounts the stimulus behind the “Great Levitation” – a rise that has subsequently turned into the biggest and baddest bull of all time.

CHAPTER 4: UP FROM THE ASHES

Welcome to the longest bull market in history! What a run it’s been!! Many media sources have covered this remarkable development—with some criticism of its accuracy—but what hasn’t received any attention is another possible streak. Should the S&P 500 finish the year in the black, it will be the tenth straight of positive total returns. That has never happened before in the history of this venerable index, which dates back to 1928.

After so many years of relentlessly rising stock prices, it is almost impossible to recall how fear-wracked investors were a little less than a decade ago. The trauma of witnessing major financial institutions such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Lehman, and Washington Mutual collapse in the early fall of 2008—with other behemoths such as AIG and Citigroup surviving only due to massive government bail-outs (but still essentially wiping out shareholders)—was too much for many to bear (pun intended!).

Just months before what would soon be known as the Global Financial Crisis, it appeared that problems in housing might merely cause a mild recession. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke had assured the public that the melt-down in the mortgage market would stay “contained” within sub-prime loans. Other high government officials, like Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, assured investors in Fannie and Freddie that those two “Government-Sponsored Entities”, or GSEs, were safe and sound. Within months, both Mr. Bernanke’s and Mr. Paulson’s soothing words would be proven to be utterly unsound.

It was almost like what had happened in another September, seven years earlier, on 9/11/01. Americans woke up one day and the world they had known was forever changed. Fear had replaced complacency and the speed with which it happened made it feel like some kind of terrible dream. In reality, the 2008 crash was another national nightmare and one that continues to haunt us to this day, despite the seeming invincibility of the S&P 500 (at least as I write these words).

After initially greatly underestimating the magnitude of the crisis, the Fed flew into action with a bold series of moves. It guaranteed money market funds which had suddenly become suspect in the minds of investors, causing a run on these widely-held vehicles that were once considered riskless. It provided enormous sums of desperately needed dollars to foreign central banks. And, perhaps most significantly, the Fed prepared to launch its first round of Quantitative Easing (QE) whereby it willed into existence $1 trillion of reserves with nothing more than a few computer keystrokes.

This money-from-nothing was, of course, unprecedented. Never before had the central bank of a wealthy country resorted to such an extreme monetary policy. It was intended to instill confidence and stabilize the system, but it had an unintended consequence. Because we have become so numb to QEs over the past decade, we also forget the chorus of supposedly expert voices who warned that such overt money printing* would lead to inflation, possibly of the hyper-variety.

One reason I vividly remember this aspect is that for at least the first few years after QE 1.0 was launched—with two more iterations to follow—I repeatedly found myself in the position of debating the subject with clients and other investment professionals. Many of them contended that inflation was inevitable and, moreover, that it was exactly what the US government wanted in order to inflate away its debt. (The Federal deficit was exploding in those days due to the Great Recession and the numerous bail-outs that also included GM and Chrysler).

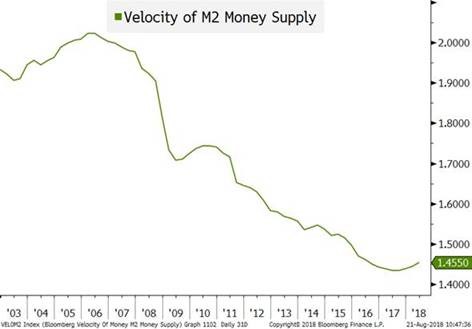

My counter-argument was that offsetting the stimulus from the trillion-dollar QE was something of which very few people were aware: the velocity of money. At the same time that the Fed was synthesizing its first trillion, money velocity was cratering at a rate unseen since the Great Depression.

*In reality, QE actually was the creation of digital reserves that the Fed used to buy treasury bonds from the banking system.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Yet, because most people had never heard of the velocity of money and were only focused on the sheer quantity of Quantitative Easing, they fell victim to the idea that yield securities were to be avoided. This was most unfortunate—and likely cost investors hundreds of billions if not trillions in lost income as well as capital gains—based on the fact that high cash flow issues like non-government guaranteed mortgages, corporate bonds, and preferred stocks were selling at prices unseen since the early 1930s. During the worst of the crisis, junk bonds were trading at yields of around 23%.

Additionally, other income vehicles like master limited partnerships (MLPs) and real estate investment trusts (REITs) were mercilessly pummeled, with their prices often slashed by 60% or more. In some cases, cash flow yields on MLPs were over 30% and, in almost all instances, their distributions held.

As a consequence of this meltdown, Americans were not only terrified, they were furious. They were livid that policymakers had been blind to the mortgage fiasco that many, including this author, had warned about for years. They were incensed that their money was being used to “bail out Wall Street”.

It was in late 2008, during the worst of the panic, that Congress reluctantly passed the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). This legislation provided for the US Treasury to infuse capital into large banks and insurance companies in return for a high interest rate and also, critically, an equity stake. Of course, with all financial equities having been crushed, the government was getting shares at give-away prices.

This caused me to write at the time that the Treasury would eventually earn windfall profits. To say this view generated widespread derision is putting it most mildly. Many people thought I had lost it (an opinion I’m hearing a lot again these days!). As we now know, TARP was a monster moneymaker for taxpayers.

But, back then, the mantra was “Bail Out Nation” and the anger eventually led to the “Occupy Wall Street” movement (bet you forgot that one!). For those of a less militant nature, which would be most investors, the mindset was not so much vitriolic as it was paralytic. They were too traumatized to buy anything, despite the yields mentioned above, even once it was clear the financial system would not implode.

Evergreen did multiple investor presentations during the worst of the panic and more after the rally was gaining momentum. Consequently, we had first-hand knowledge of how catatonic almost everyone was at the time. Over and over, we would give an impassioned plea to our audiences about the incredible opportunity to lock-in double-digit yields and position for capital gains as prices recovered. Over and over, we received mostly blank stares.

Investors were either too emotionally scarred by what they had just gone through or they had heard all the hyper-inflation chatter. Either way, very few were willing to move cash from money funds into things like MLPs. Getting them to open an account to buy stocks was virtually impossible--though we tried. During our “campaign”, often to clients of two leading discount brokerage firms, we opened a handful of income accounts, but it was definitely not a LeBron James handful—more like Joe Pesci.

It’s ironic these days, when so many view me as a perma-bear, to think back to 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, and even into 2012 and how much flak we took for being bullish, especially for preferring US stocks to the then-soaring international markets. Existing clients were happy, but it was like pulling wisdom teeth to attract new investors. It wasn’t just us; trillions were earning almost nothing in money funds even as the stock market doubled off its lows (after falling by almost 60% from the 2007 peak to the 2009 trough).

Meanwhile, junk bond yields were tumbling from 23% to the mid-teens and then into the single digits, as millions missed the chance to make billions. Many MLPs were in the process of tripling or more. Even high-grade corporate bonds were producing 30%-type returns off their late 2008 lows and preferred stocks in major financial institutions were posting total returns of 50% during the first year of the recovery (with many more years of double-digit returns still to come).

Part of the reason investors were so reluctant to re-engage with financial markets was due to the dire warnings that continued to be issued by many of the experts who were among the few to warn of the mortgage mayhem. Despite a stock market that had been more than cut in half, predictions of much greater declines—like Dow 5000—were commonplace. And because these individuals had considerable credibility based on their housing crisis calls, it was hard to dismiss their views. One of these experts, whom I personally respect very much, repeatedly predicted a second Great Depression well into the recovery.

John Hussman, another person who saw the disaster coming, has frequently admitted the mistake he made by stress-testing for a replay of the early 1930s when stocks fell 80%. As this newsletter has noted before, he had the chance to buy securities at Depression-like levels—if he had been willing to venture into the world of yield securities but he missed that opportunity, as well. In this business, it’s a given you are going to make mistakes—as I have by being worried about US stock market overvaluation for the last five years—but to John’s great credit he has been totally forthright about his big whiff. (By the way, he remains convinced the S&P 500 will, once again, lose at least half its value, as it has twice since 1999.)

Unlike John Hussman, many of those who were adamantly telling investors to stay out of stocks after the crash seem to have developed amnesia about the message they were conveying back then. For my part, it was just as lonely to have been a bull back in 2009 and 2010, despite tremendous support from the Evergreen team, as it is to be a bear these days.

Due to the pervasive pessimism in the early years of the rise from the abyss, valuations stayed attractive. As late as the summer of 2011, over two years into the new bull market (remember, the previous one lasted only five years, from 2002 to 2007), the median P/E ratio on the Dow was just 12.

The income realm was a different story, however. Double-digit yields were long gone. MLPs and REITs had continued their furious rally that started in November, 2008 and March, 2009, respectively. By mid-2012, investment-grade bonds yields were a miserly 4% and the interest rate on junk bonds got down to 6% by summer’s end.

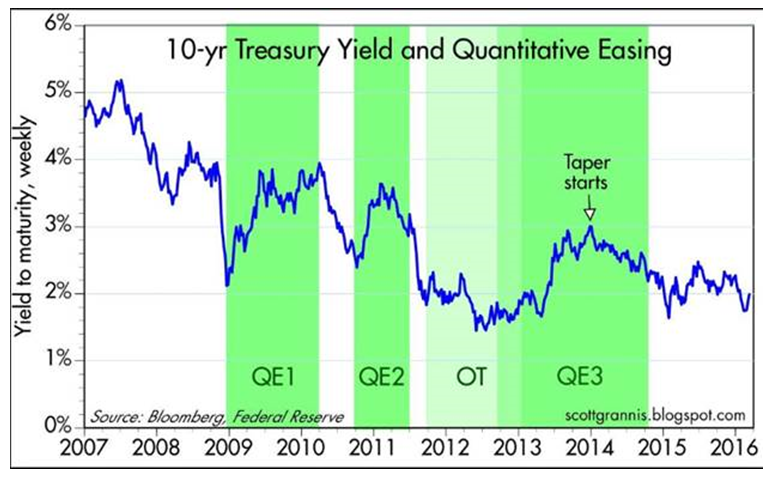

There were reasonable fears, though, that once the Fed quit creating money to buy government bonds, rates would rise dramatically. Yet, as with inflation, there was a surprise playing out. Treasury yields actually fell in anticipation of QEs 1.0 and 2.0 but then rose as the Fed was buying. Once the programs ended, rates declined again. (By the way, “OT” on the following chart refers to “Operation Twist”, another Fed initiative that, in this case, attempted to force down longer-term interest rates.)

To the Fed’s great vexation, unemployment remained stubbornly high in the early years of the expansion, leading it to believe more monetary uppers were needed. In the fall of 2012, over three years into the economic up-cycle, it launched QE 3. The third iteration would turn out to be the biggest of all, eventually totaling $1.6 trillion.

By the time it finally turned off its magical money machine in October of 2014, the Fed’s balance sheet had exploded from around $700 billion pre-crisis to a stunning $4.5 trillion. Please realize this was all done with “fake money”, the aforementioned digital reserves the Fed created on its computers that it used to buy treasury bonds and government-guaranteed mortgages. There is little doubt much of this spilled over into asset prices, either directly or indirectly. (An indirect example is that by collapsing interest rates, the Fed encouraged publicly-traded companies to leverage up to buy-back their own shares, to the tune of about $5 trillion since 2010).

In addition to fabricating almost $4 trillion, it also maintained interest rates at essentially zero until meekly hiking rates in December of 2015. In other words, the Fed kept the monetary pedal to the metal over five years into the recovery cum expansion. (Technically, a recovery is the post-recession phase that returns GDP back to its prior peak and the expansion is the GDP increase that occurs thereafter.) This was totally unprecedented in the annals of Fed monetary policy.

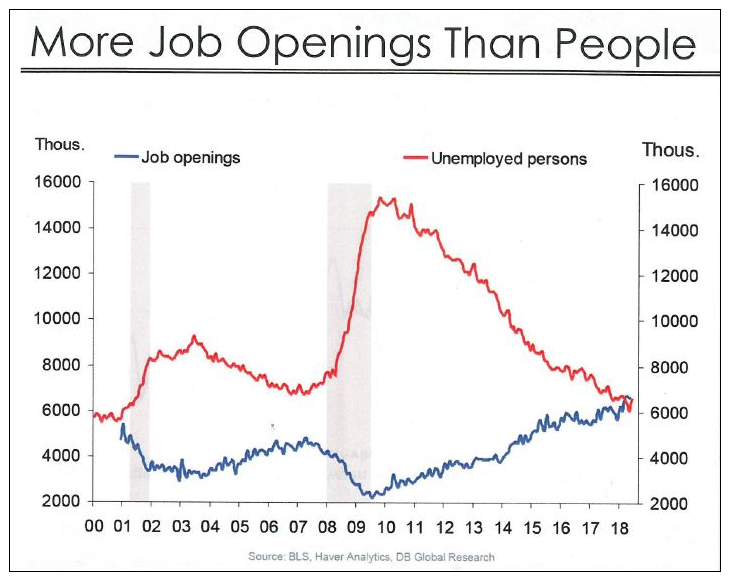

Despite this unparalleled largess, and a near doubling of the national debt (i.e., tremendous monetary and fiscal stimulus), not only was the jobless rate stubbornly high for many years, the expansion also turned out to be the weakest on record. Notwithstanding a strong second quarter of 2018, it continues to be by far the feeblest economic up-cycle in the post-WWII era. This is particularly disappointing given that the jobs market—once such an overarching concern for the Fed—is extremely strong. (By the way, historically, the worse the recession, the stronger the recovery and expansion—and those prior vigorous rebounds were achieved without multi-trillion fiscal and monetary stimulus.)

Source: John Mauldin, Over My Shoulder

Source: John Mauldin, Over My Shoulder

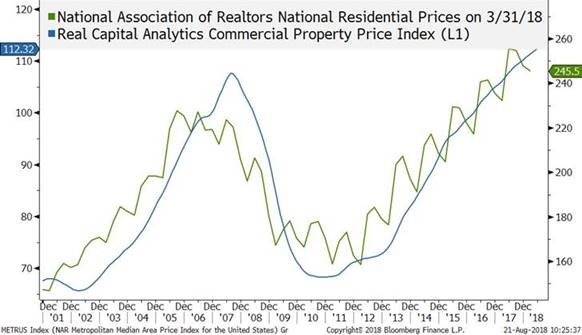

As a result, it’s reasonable to question the efficacy of this epic experiment in flooding the system with liquidity and debt—at least as far as the economy is concerned. As noted in numerous past editions of the Evergreen Virtual Adviser, it has been a completely different story for asset prices. It’s hard to find a major asset class that hasn’t been driven up to bubble-like prices.

For example, few would have foreseen that, out of the smoking rubble of the real estate crash of a decade ago, prices would eventually exceed their 2007 peak. But that’s exactly what’s happened for both commercial and residential properties.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Time will tell whether it was wise to deal with the aftermath of a debt and real estate mania with more debt and another property bubble. But if you’ve been tracking the price action of Zillow and Redfin lately, you might suspect that time is finally starting to tell. Here’s what Redfin’s CEO recently had to say: “For the first time in years, we are getting reports from managers of some markets that homebuyer demand is waning, especially in some of Redfin’s largest markets…The trend is continuing in July and reports are coming in from Washington, DC, Boston, Virginia and parts of Chicago as well that homes there are getting harder to sell.” (By the way, residential real estate brokers in the Seattle area have confirmed this dramatic shift to me recently.)

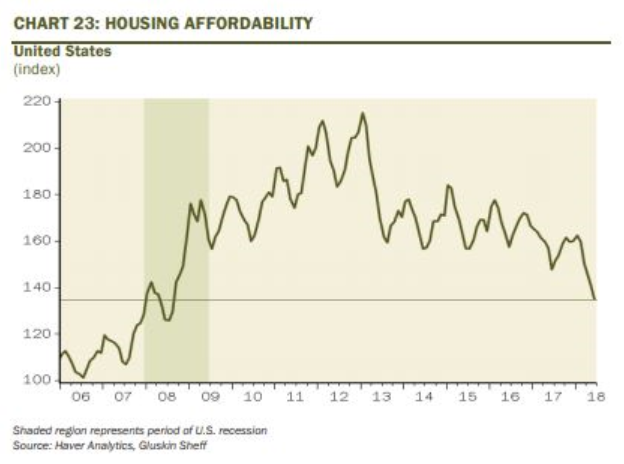

A key reason for this sudden weakness in housing prices could certainly be a function of the collapse in affordability over the last five years. Ominously, affordability is now the worst it has been since—gulp—2008. The magnitude of the deterioration seems to have hit a tipping point lately per the preceding quote from Redfin’s CEO. With the Fed determined to keep raising interest rates, the downtrend shown below may be destined to continue.

Source: Haver Analytics, Gluskin Sheff

Source: Haver Analytics, Gluskin Sheff

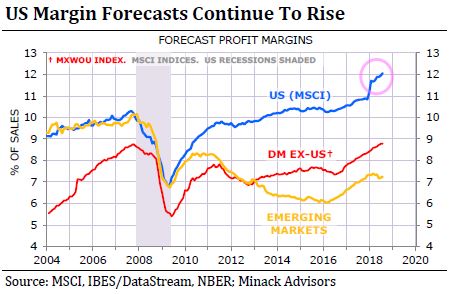

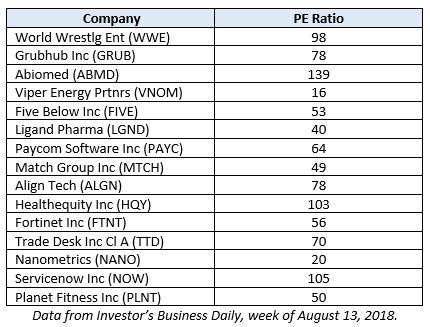

Unlike with housing, the US stock market is showing few obvious signs of cracking. However, despite the repeated reassurances from market pundits about how reasonably the S&P 500 is priced—usually based on corporate earnings that are very unlikely to be sustained (see the margin chart below)—there are a slew of stocks trading at 1999-type multiples. The below is from a recent

Few investors, even of the most optimistic variety, would have imagined--after witnessing the seismic financial fissures which cracked open ten years ago--that a decade later so many stocks would command such extreme valuations. But then again who would have envisioned back then that after years of economic and financial market recovery central banks would still be operating with monetary policies suited for a mega-crisis? After all, it was just last year that global quantitative easing hit its crescendo. As of now, it’s only the Fed that has begun to reverse gears and has started pulling the floodtide of liquidity out of the system (i.e., initiating the unwinding of its various QEs).

Similar to how almost everything seemed to go wrong at the same time back in 2008, during this incessant rise out of the post-crash rubble almost everything has broken to the good. When it looked like Europe was imploding in 2012, European Central Bank (ECB) head Mario Draghi promised to do whatever it took to prevent a euro collapse. Whenever earnings faltered, the ECB and other central banks have ridden to the rescue. When it appeared that the lift from money-for-nothing (or less than) was losing its anti-gravity effects, Donald Trump’s election provided the next booster stage. As the confidence surge from his win began to ebb, the massive corporate tax cut was passed just in the nick of time.

It’s been truly a remarkable decade, with a script no one could have credibly created 10 years ago. I’m not aware of any prophet of doom who foresaw how terrible things would become back in August of 2008. Nor do I recall any starry-eyed optimist who foresaw how long and powerful the US stock market recovery would be once it hit bottom, a rally that has left the once-idolized overseas markets in its dust. Remarkably, this has all happened despite the limp and heavily stimulus-reliant economic expansion.

It also occurred notwithstanding intense skepticism among the investor class toward Barrack Obama who was inaugurated mere weeks before the stock market bottomed. You could have received huge odds in early 2009 betting that the S&P 500 would post positive returns for eight straight years with Mr. Obama in the White House. And yet that’s exactly what happened with another year and two-thirds under Mr. Trump, even though his economic policies have been radically different.

If you are looking for the common thread between the Obama and Trump stock market rallies, you may not need to look much further than share buy-backs. That’s been the one main constant. The good news for bulls is that they are running at their hottest pace yet, with no sign of cooling. The bad news is that at some point they will drop off, probably dramatically. When they do, there will remain trillions of dollars of debt incurred, along with all of the interest required to service the additional IOUs.

Unfortunately, what gets scant press—for now—is how much of the share repurchasing has been offset by management stock options. In the next bear market, the trillions of high-priced buy-backs may not be viewed quite so favorably by bag-holding investors.

But, regardless, this has been one rollicking bull market in almost everything. Central bankers of the world, unite—and take a big bow. But remember that even you and your mighty printing presses can only delay market cyclicality, not eliminate it.

Before they can declare they’ve won the war, and not just a battle, the next market down-turn better not look like the last two. For those that think I’m blowing smoke, consider the impact the last two market down cycles have had on very long-term investment returns. Because of how expensive stocks became in the late 1990s, and again in 2007, when the prior two bear markets hit, it meant that for 14 years—from the end of 1997 until nearly the end of 2011—the S&P 500 actually underperformed T-bills!!

S&P RETURNS VS. T-BILLS, 1998-2011

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

As all of us in the Pacific Northwest are uncomfortably aware, our normally pristine part of the planet is once again engulfed in smoke from hundreds of fires. There are undoubtedly multiple causes. However, many believe the reluctance on the part of the responsible government agencies to do controlled burns has been a major factor, along with their overzealousness in putting out small fires. The normal cleansing out process has thus been inhibited with disastrous results.

The Fed and its overseas equivalents may also discover that by suppressing market cyclicality for so long, when it does return it may come blazing back with an intensity that resembles the conflagrations raging up and down the west coast right now. If so, they may also find out how hard it is to put out market infernos once they are really roaring.

Source: International Business Times

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

Changes highlighted in bold.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

* Credit spreads are the difference between non-government bond interest rates and treasury yields.

** Due to recent weakness, certain BB issues look attractive.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.