“Your actions speak so loudly, I can’t hear a word you’re saying.”

– Former NFL head coach, Chuck Knox

“High public debt often produces the drama of default and restructuring. But debt is also reduced through financial repression, a tax on bondholders and savers via negative or below-market real interest rates…Financial repression is most successful in liquidating debt when accompanied by inflation.”

– Carmen Reinhart and Belen Sbrancia, in their 2015 IMF Working Paper, “The Liquidation of Government Debt”

“Confused by the Fed? So are the markets.”

– The Wall Street Journal’s James Mackintosh

“Talking about rate changes now isn’t even on the table. The mantra right now is: steady on the boat.”

– San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly

“The real (after inflation) fed funds rate has actually fallen from -1.125% a year ago to -3.8% today. So while FedSpeak has turned more hawkish, Fed actions have actually turned more dovish…”

– Jesse Felder, author of The Felder Report

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Summary

Don’t Fear the Fed

One of Wall Street’s most hallowed phrases is “Don’t Fight the Fed” and for good reason. Whether it was the 2016 deflation scare, the stealth pre-Covid recession, or the pandemic itself, the Fed’s unlimited liquidity creation has triumphed over all threats to the US stock market. But, based on the reaction to the June 16th press conference by Fed chairman Jay Powell, I’d like to create a bit of a twist on those sacred words.

For those of you unaware of its impact, that “presser” created what some financial commentators are referring to as “Taper Tantrum, 2.0”. This is in reference to the original market tantrum, way back in May of 2013, triggered by then Fed-head Ben Bernanke. That iteration triggered turmoil in both stocks and bonds (creating an excellent buying opportunity in yield securities which this newsletter suggested acting on at the time).

In the wake of Taper Tantrum, the sequel, I’m going to suggest that the revision to the aforementioned famous statement should be “Don’t Fear the Fed”. In fact, I would go so far as to say that the market convulsions caused by the mid-June Powell Presser were actually somewhat ridiculous. Ok, let me rephrase that—strike the “somewhat”.

For starters, the perception that the Fed shifted from ultra-dovish to even mildly hawkish with a few less than virile words, strains credulity. The two main causes of the perceived dove-to-hawk metamorphosis were the indication that it might raise rates twice in late 2023 and that it is now no longer not talking about talking about tapering asset purchases (hence, the taper tantrum aspect). Sorry for the double-negative but when it comes to Fed, and its propensity for double-talk, those are hard to avoid.

Whatever spin one might want to put on this alleged attitude shift, it is certainly light-years removed from the brute force exerted by Paul Volcker in the early 1980s to squelch double-digit inflation when he drove short-term interest rates to 20%. One could reasonably argue that today’s 4% to 5% CPI increases don’t warrant anything close to such a draconian reaction. Fair enough, but let’s focus on what the Fed is actually doing in the wake of this supposed big change.

Is it actually reducing asset purchases? Nope, these will still run at about a $1.5 trillion dollar annualized rate. Is it going to raise rates somewhere near the inflation rate? Hardly—the Fed is projecting that it might get up to 0.75% by year-end 2023, which is at least 3% below the current CPI. Moreover, that is even well below the 2% inflation level it is assuming we’ll return to once supply chain bottlenecks and shortages of almost everything are resolved.

Market behavior since the momentous media event does seem to validate the view that this is a baby step by the Fed, not a giant leap toward monetary prudence. Stocks had a rough couple of days and then came roaring back. Bonds barely flinched. Both of these mild reactions are in stark contrast to the multi-week turmoil seen in 2013 when the S&P dropped 5.8% and the 10-year Treasury fell by 10.66%, pushing its yield up to 2.995%, an increase of roughly 84%. In the once en fuego commodity complex, though, it was a very different story…

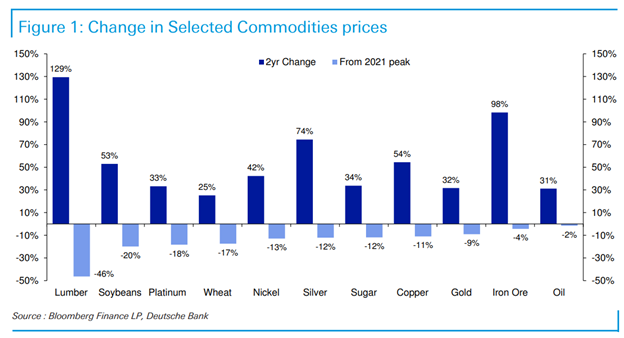

As you can, see the latest Powell Pivot, such as it was, intensified a correction—one that started earlier this spring--in pretty much all hard assets; I say pretty much because there was a very notable exception that I’ll cover shortly.

For those who missed our May 28th EVAon the extreme focus on inflation and the related raging bull market in commodities, this was a scenario about which I cautioned. Here’s a brief excerpt from that issue: “Yet nothing moves in a straight line in the real or financial world. Despite impressive long-term breakouts, almost all commodities look extremely stretched and poised for a sharp decline (some of which is already occurring). Economic growth readings such as we’ve seen lately are going to be very tough to sustain…”

At that point, for example, lumber was already 22.3% off its high but it would tumble another 45.32% (it is now down even more from when this image was produced). Since lumber had risen by far the greatest amount, it was most vulnerable to a severe decline and that’s obviously what has happened. For most of the rest, it’s been a painful but not shocking correction.

As also discussed in our May 28th letter, the economy’s growth rate has shown signs of decelerating and, as I suspected, this has caused pundits like David Rosenberg to engage in a bit of chest puffing. This has emboldened him to call for weak growth in the second half of the year. Yet, as often as I have praised David in these pages over the last 17 years, I have to say that I disagree with his tepid economic outlook.

Certainly, a moderation of the torrid pace seen this spring is almost a statistical certainty. But with the service side of the economy beginning to rip—which is far larger than the goods-producing side – I have a hard time seeing anything but a very robust third and fourth quarter—barring a market crash, or crashette. Neither of those are my base case but they also aren’t improbable. Again, more on that in a bit.

One of David’s main reasons for seeing a soft second half is due to what he refers to as a fiscal cliff. This is the idea that the wartime-like degree of federal spending seen over the last sixteen months is going to do a Thelma and Louise. However, based on the $6 trillion budget proposed by the Biden administration for the upcoming fiscal year (starting October first), I simply don’t buy that logic.

Earlier this year, when the Fed and David Rosenberg saw both a subdued recovery and inflation, this newsletter predicted that we could see a 10% quarterly GDP number, possibly two, with the CPI surprising on the upside, as well. That 10% GDP may or may not happen (it could be close for Q2) but, regardless, it’s been a remarkably strong first two quarters. Now, even Jay Powell is recognizing the considerable economic momentum per these words from his press conference: “I am confident that we are on a path to a very strong labor market that—that shows low unemployment, high participation, rising wages for people across the spectrum…and if you look through the current timeframe, and think one or two years out, we’re going to be looking at a very, very strong labor market.”

Please note the two “verys”. This view is shockingly more bullish than what he saw mere months ago. Thus, once again the Fed’s forecasting abilities have proven to be totally unbefitting an organization with countless on-staff economists and a nearly limitless IT budget. It has become the embodiment of another catch-phrase: “Often wrong but never in doubt.” To be fair, Mr. Powell did show some uncharacteristic—though very well-earned—predictive humility on Capitol Hill a few days after his Taper Tantrum 2.0 presser. He admitted “it’s very hard to say what the timing of that will be”, using another “very” in reference to when inflation will subside (after seriously underestimating how hot it would run in 2021’s first six months).

However, he then resorted to the same word twice when responding to a congressman who asked him if Fed policies might lead to 1970s type inflation. Per the Wall Street Journal, Mr. Powell said such a scenario is “very, very unlikely” and, further, that the Fed “is strongly prepared to use its tools to keep us around 2% inflation”. Call me paranoid (you wouldn’t be the first) but those words strike me as a case of “thou doth protest too much”.

Moreover, I’d challenge the “strongly prepared” aspect. It’s not that the Fed doesn’t have the tools to keep inflation in check but their willingness to use them is a very (sorry) different story. By raising rates to a level above even its supposed soon-to-revert-to norm of 2%, and simultaneously letting its now $8 trillion balance sheet (all acquired with its magic wand money) come down a trillion or two, it could almost certainly cool inflation. But financial markets are highly unlikely to take such a reversal of monetary largess in stride; more probably, they’d crater.

This is exactly what happened in late 2018 right after Mr. Powell told the world in October how “remarkably positive” the US economy was at the time. He further noted it was the best in nearly 70 years, which seemed a tad hyperbolic, but that didn’t stop him from halting the Fed’s feeble attempt to “normalize” rates at a mere 2 3/8% in January of 2019, less than three months after his remarkably positive commentary.

The catalyst for his about-face wasn’t economic stress; rather, it was the S&P 500 tumbling by nearly 20%. Clearly, the fed funds rate slightly over 2%, a relatively modest reversal of the Fed’s famous quantitative easings, and the prospect of further gradual tightening on the way was more than the market could handle. By July of 2019, Mr. Powell also halted the languid balance sheet shrinkage he had gingerly attempted. The S&P was off to the races once again, making a decisive new all-time high that summer.

Last week, I listened to an excellent podcast by my great mate Grant Williams and Charles Schwab’s Chief Investment Strategist Liz Ann Sonders. In it, she made an excellent point that in days of old the markets responded to Fed actions. In fact, it was her former boss, the legendary Marty Zweig, who coined those immortal words “Don’t fight the Fed”. But Ms. Sonders wonders if the Fed is now dancing to the market’s tune, even if our central bank can obviously still impact asset prices. Increasingly, though, it seems like the market is at the piano and the Fed is on the dancefloor.

Regardless, I think it’s critical to watch what the Fed does, not what it says. And what it’s doing right now continues to be incredibly stimulative, especially for an economy that is rocking and rolling like few have in the past. As Mr. Powell also told Congress last week, “Real GDP appears to be on track to post its fastest rate of increase in decades.” How that squares with a Fed in max stimulus seems like a question some congressman or reporter needs to be asking…and re-asking.

To this point, the Wall Street Journal ran a pull-no-punches op-ed right after the Powell Presser Pivot asking, “Is There A Central Banker In The House?”. Like me, its writer, Joseph Sternberg, wondered how the Fed could remain pedal-to-the-metal with the economy so rapidly recovering. He also noted that at times the Fed chairman sounded like he was reading a hostage statement “because Mr. Powell is a hostage—to the market.”

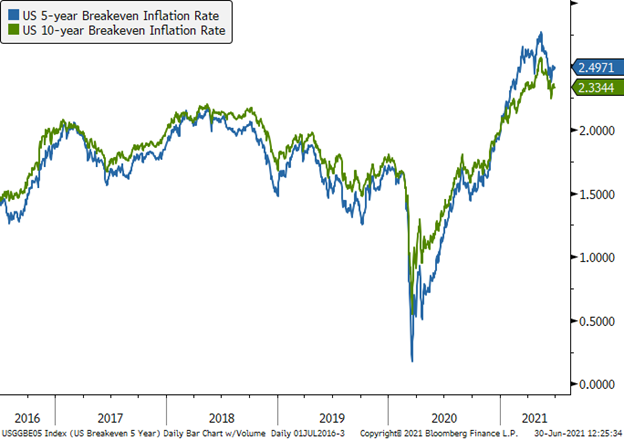

To avoid upsetting his captor, Mr. Powell needs to keep interest rates suppressed. Yet, should inflation not be as transitory as he has convinced most market participants it will be, he will have little choice but to start tightening—with actions and not just words. Accordingly, Mr. Powell finds himself in a most challenging position. As big-picture commentator extraordinaire Luke Gromen wryly observes, the Fed needs to ride two horses with but one butt. To pull off this daunting equestrian straddling trick, it needs to keep achieving what it did two weeks ago: jawbone investors into lowering their inflation expectations. Anything it can do to bring down commodity prices is a big help in that regard and that’s precisely what the Fed pulled off with its alleged hawkish pivot. As you can see, the main indicator of market-based long-term inflation expectations came down right along with commodities.

However, one commodity that refused to buckle was oil; another was natural gas. In my view, their resilience is a reflection of the factors this newsletter has been writing about pretty much since Covid crashed the energy market in the spring of last year. Specifically, that demand is coming back faster than supply. Additionally, with energy producers under siege both from their traditional investor base--that wants them to avoid all but the most promising exploration expenditures – and the new mega-force of ESG-driven* investors – who want to see them carbon-neutral – new reserve development is extremely—ahem—reserved.

On that latter point, in late May the International Energy Administration (IEA) urged a halt of all oil and gas drilling by the end of this year. Given the rapid declines rates of shale oil and natural gas—the main drivers of the planet’s energy output growth over the last decade—adhering to the IEA’s recommendation will soon create a shortage that would make the 1970s look benign. Even without such a radical—and, in my opinion, extraordinarily reckless and unrealistic—development curtailment, the oil market looks headed for a severe supply shortfall before long.

Consequently, also in my opinion, we are barreling into the world’s third oil crisis. If so, this has significant inflation consequences and will make the Fed’s two-horse routine even more challenging…if not downright impossible. The market seems to be sniffing this out; hence, the notable upward grind in crude prices despite the now “hawkish” Fed. (This is not to say corrections won’t happen even with a supply situation that is becoming hermetically-sealed tight; pull-backs are almost inevitable but I continue to believe we will see triple-digit prices next year, if not sooner.)

*Environmental, social and (corporate) governance-focused investing; some wags might call this PC investing and I don’t mean as in personal computers.

Because I went over what I believe are the long-term factors that will continue to push inflation to persistently uncomfortable levels in the May 28th, EVA, I won’t rehash them, save for one: wages. Since I wrote that, evidence of rapidly rising labor costs has been mounting. It is unlikely this trend will recede like lumber and used car prices. Wages are notoriously sticky. They are likely to stay elevated and, probably, move even higher--especially if energy costs continue to soar (increasing the need for higher worker compensation). If so, this makes the Fed’s two-horse trick even more difficult.

Yet, its overarching goal—even if it doesn’t admit it—is now to keep rates low to allow the US government to continue to borrow inexpensively. Of course, by purchasing treasuries with fabricated funds it makes that even more painless (the Fed remits the interest on the trillions of government debt it holds right back to the Treasury; now that’s a neat trick indeed!). Showing how embedded this is into the government’s borrowing plans, the White House is now projecting interest rates to stay below inflation for the next decade. Look out bond buyers—you’ve got a bulls-eye on your backs!

Per last week’s Guest EVA by Vincent Deluard this is no country—or central bank--for old bond investors (aren’t almost all fixed income holders “mature”?). For those in the stock market, it’s a much happier story, as Vincent also noted. This Fed, like the three or four before it, has gone to all lengths to keep the S&P marching higher. That paradigm is unlikely to change anytime soon even if fears of persistent inflation cause a serious sell-off (the crash and/or crashette scenario). In that case, I wouldn’t put it past Powell & Co. to buy stocks using its Magical Money Machine, as the Bank of Japan and the Swiss National Bank have already done. Such a Fed reaction would almost certainly be rocket fuel for the economically-sensitive and resource-based sectors that were slammed in mid-June by Mr. Powell verbal pivot. Per my partner and great friend, Louis Gave, this may be the last chance to hop on the commodity train…at least for a cheap fare.

As Vincent wrote last week, with words so on the mark I thought they were worth repeating: “The U.S. really wants higher stock prices and can let go of its currency and bond market. If anything, a decade of financial repression, inflation, and a weaker U.S. dollar may be secretly desired by smart populists who understand that these are the necessary conditions to rebuild the manufacturing heartland of the country, reduce wealth inequalities, and default on the unsustainable entitlements that the boomer generation granted itself.”

Obviously, the Fed must play the starring role in making the above scenario become reality. If that sounds like a central bank you need to be frightened of, I’d suggest you shouldn’t go outside very often this summer. The sight of your shadow might be too much for you to handle.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.