“We are of different opinions at different hours, but we always may be said to be at heart on the side of truth.”

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

This week’s EVA features two recent pieces: Is Wall Street in a Bear Market? by Anatole Kaletsky and Here Comes Daddy Bear by Charles Gave. Below is a brief summary of each author’s piece:

Anatole Kaletsky: Is Wall Street in a Bear Market?

- The US is not in a bear market.

- Bear market officially begins at -20%, currently US market is down 12%.

- The recent market decline is a “pause that refreshes.”

- This current market has survived a variety of scares like this already i.e.:

-In 2010, US budget deficit worry, down 15%

-In 2011, Treasury default fears, down 19.5%

-In 2012, euro crisis, down 10%

- During this bull market, corrections have been buying opportunities.

- Keep an eye on three fundamental issues: China, Oil, and US/World Recession

- China: If they lose control of exchange rates, it could trigger widespread panic

- Oil: Low oil prices are a good thing for economies as it really equals cost savings

- US/World: Stocks, historically, have performed well in times of low oil prices. If prices move higher that could be a headwind.

Charles Gave: Here Comes Daddy Bear

- There are two types of bear markets: “cub” and “daddy” bears.

- In a “cub” bear market: 15% type corrections occur over 12-18 month which are just “pauses along the way.”

- Ursus Magnus (“daddy bear”): In this type of market decline, it will take you 4 years to recoup your losses. In the last 45 years there have been 3 such episodes.

- Normal bear markets are when share prices/exuberance get too high.

- Ursus Magnus occurs as a result of a misallocation of capital. (Evergreen’s comment on misallocation: Exceedingly low interest rates fueled over-investment in the energy space as well as record amounts of share buybacks.)

- Major bear markets need two key things to form: Exceedingly low rates for an exceptionally long time.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

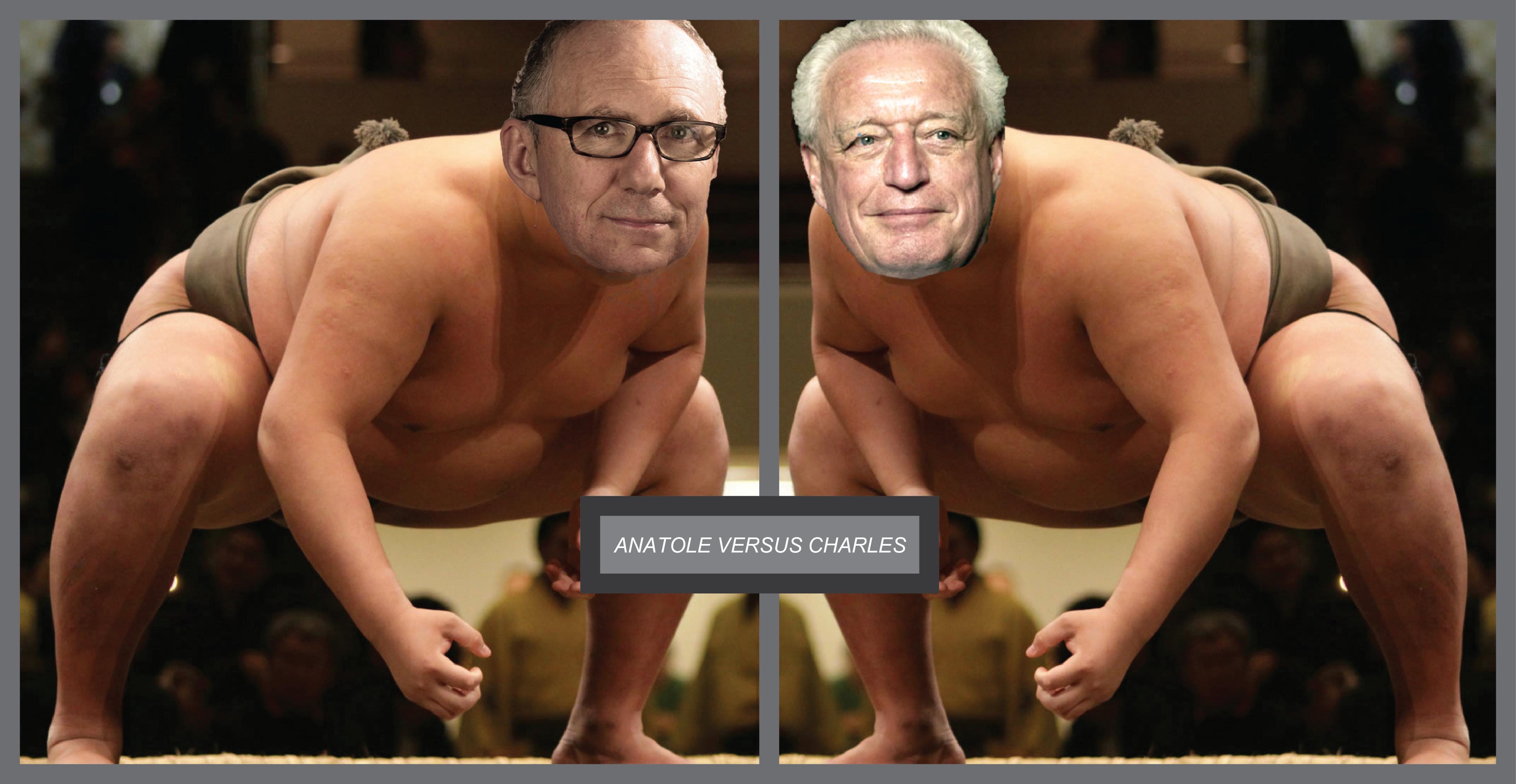

WRESTLING FOR ANSWERS

In this week’s Evergreen Virtual Advisor (EVA), two of the financial world’s keenest thinkers tussle over what is top of mind for virtually every investor these days. In their respective essays, our senior partners at Gavekal Research, Anatole Kaletsky and Charles Gave, discuss whether or not we are headed for a true bear market or just another mild and brief correction. Both display sound logic, strong opinions, and agree on virtually nothing.

It is our pleasure to bring our readers a behind-the-scenes look at the exceptional work that takes place at Gavekal on a daily basis. We feel fortunate to have access to their thoughtful research and incorporate it into our outlook and client portfolios. We hope you will find this week’s piece as informative and entertaining as we do.

We ask that readers make their voices heard by casting a vote based on who you think is right.

Finally, to readers who enjoy our weekly effort to keep you informed (though some readers have said they use our piece to help them fall asleep), passing EVA along to your friends and peers is the finest compliment you can give us.

IS WALL STREET IN A BEAR MARKET?

By Anatole Kaletsky

As Shakespeare said, “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet”; but he then forced Juliet to discover to her tragic cost that names sometimes really do matter.

The significance of “bear market” nomenclature is not whether a peak-to-trough fall exceeds the supposedly “official” 20% definition, since there is no significant difference between the pain of a 19% or a 21% loss. By that definition, of course, US equities are still quite a long way from “bear market territory”, since the S&P 500 is down only -12% from its record high of May 2015, and even the average stock, as measured by the S&P 500 equally weighted index, is down just -16%.

The real point, as Charles rightly stated in his blood-curdling Ursus Magnus piece last Friday (right column), is that a genuine bear market keeps relentlessly torturing investors who are rash enough to buy stocks—and keeps up the punishment for years on end. Charles, in fact, boldly defined a serious bear market as a downtrend in which investors who buy at the top do not recover their money for four years or more. By contrast, he dismissed a -15% to -20% decline lasting less than 18 months as a mere bear cub that could equally well be described as a “pause that refreshes”.

I fully agree with Charles’s analysis, which captured eloquently, as usual, a key financial issue. However, in my view, this analysis leads to the opposite of Charles’s conclusion that the present decline has all the markings of an Ursus Magnus. On the contrary, it looks rather more like a “cub”, or even a “pause that refreshes”.

The present market setback has not lasted four years, nor even one year. Only nine months have passed since the peak of May 21. Although it is possible that the present decline will get much worse and continue for many years, there is at present much more evidence against, rather than in favor of, such a prediction. This is true not only of the economic fundamentals but also of the market’s internal behavior.

As everyone knows, the upsurge in equity prices that started on March 10, 2009 has been among the most despised and distrusted bull markets of all time. As a result, the bull trend has been regularly interrupted by corrections roughly as large and as scary as the one today. These setbacks have been triggered by a variety of scares, with newfound horror stories materializing on roughly an annual basis. In 2010, the catalyst was fear about the US deficit, which set off a -15 % correction. In 2011, panic about a US Treasury default sent the S&P down -19.5%. In 2012, the euro crisis caused two corrections, -10% in the spring and then -8% in the autumn. In 2013, the panic was about Federal Reserve tapering and a US government shutdown, although these only hit the S&P by -6%. In 2014 carnage in the Middle East and Ukraine catalyzed an -8% setback. And last summer, it was the policy blunders in China that caused a correction of -12%.

Each of these corrections turned out to be a buying opportunity, although the jury is still obviously out about the rebound in September and October last year. But given the consistency of this experience, the question we should now be asking is not whether US monetary policy has been fundamentally unsound ever since 2009 (or even since 1998, as Charles has argued when lambasting Alan Greenspan). We can leave that debate to economists and historians in future decades, when a proper accounting will be possible for the effects of quantitative easing, zero interest rate policies, the global financial crisis and the great moderation. In the meantime, it seems more sensible to focus on the causes of the present market setback and judge whether these problems are likely to last longer and cause more damage than previous panics, such as the US deficit and euro crisis, which have now been forgotten.

Three worries now seem to dominate the markets: China, oil and the risk of a US or global recession.

China is surely a big enough problem to throw the world economy and equity markets off the rails for the rest of this decade and create a structural bear market lasting many years. But this will only happen if and when Chinese authorities lose control of the renminbi exchange rate and suffer a devastating capital flight. Such a scenario seemed possible, or even plausible, for a few weeks back in August and again in the first days of this year. But in the past two weeks the balance of power seems to have moved in favor of stability in China. Nevertheless, this is a genuinely enormous and alarming uncertainty and justifies close attention to Chinese capital market policy and the monthly figures on China’s foreign exchange reserves.

What about the link between low oil prices and falling stock markets? This seems to me not just an overreaction, but a rare case when markets get an economic relationship exactly the wrong way round. The correlation between oil prices and stock markets should be—and probably will be—negative, rather than positive, in anything but the very short term. Oil prices plunging by -10% daily is obviously disruptive in the short term, causing credit spreads to explode in resources and related sectors, and forcing leveraged players to sell equity assets to meet margin calls. Luckily, this period of market panic now seems to be ending, for the reasons suggested 12 days ago and strongly confirmed last Friday by the Economist publishing a cover story on the world “drowning in oil” (Evergreen note: the Economist is famous for often running ill-timed cover stories.) Once oil prices settle in a new trading range, the lower this trading range turns out to be, the better for the world economy and non-commodity businesses, since low oil prices increase real incomes, stimulate spending on non-resource goods and services and boost profits for energy-using businesses. At the same time the “good deflation” caused by lower oil prices will limit the squeeze on profit margins from rising nominal wages.

Finally, what about the risk of a US recession? The idea that falling oil prices are a leading indicator of falling economic activity or asset prices, now widely believed by investors, is wrong as a simple matter of history. On the contrary, every global recession since 1970 has been preceded by a big increase in oil prices, while almost every decline greater than -30% has been followed by accelerating growth and stronger equities. Of course, past performance is no guarantee of future results. But the widespread belief that plunging oil prices are a leading indicator of recession is a case of “this time is different” thinking par excellence. Meanwhile, looking outside the commodity sectors and closely related capital goods industries, there has been very little evidence of a serious weakening in either macroeconomic data or corporate results—not in the US and certainly not in Europe, where growth remains fairly anemic by US standards but is nonetheless responding better to Mario Draghi’s QE program than almost anybody realized even a few months ago.

In view of all the above it seems premature to call what’s happening on Wall Street a structural “bear market”, still less a structural Ursus Magnus likely to last for many years. Unless China loses control, this still looks more like a temporary panic, leading to buying opportunities, similar to those that occurred repeatedly since 2009. That doesn’t mean that markets have put in a solid bottom or that we should try to catch falling knives. A retest of last week’s lows, and the almost identical bottom hit last August, could easily fail and take prices much lower. But with the oil markets apparently stabilizing, at least for the time being, and the central banks preparing to ease or at least make soothing statements, investors should at least remain open-minded about a resumption of the bull market that started in March 2009 and could have many more years to go.

HERE COMES DADDY BEAR

By Charles Gave

For the last few months I have been concerned that a bear market was likely to unfold. It is my considered opinion that we are now on such a trajectory. Of course the next question has to be what kind of bear market, for history suggests that such episodes come in two distinct extremes.

There are multiple definitions of an ursine market environment with the most common being a -20% top-to-bottom drawdown in a benchmark index. For me the “cub” variety of bear market involves a minimum -15% fall in the index over a year, with overall declines confined to a 12-18 month period. Such episodes are not too much of a concern as they can, in fact, be the “pause” that allows a market to be refreshed.

The second variety I think of as Ursus Magnus, or the big daddy of bear markets. It has long been thought that the lactating female bear was the most fearsome of the species, but the male is increasingly recognized as a more predatory and more dangerous creature. How to know that a bear market is of the big daddy variety? Simple. If I have not recovered my money four years or more after the declines started; in this case, I must have crossed the path of a genuine Ursus Magnus.

In my career, I have met a few bears on the track, but not so many of the latter variety. Indeed, over the last 45 years there have been three such episodes: 1970-1980, 2000-2003 and 2008-2009. In trying to identify the animal ahead, I begin with a simple contention: normal bear markets take place because share prices have reached too high a level. The story is very different for Ursus Magnus.

For me, these more serious bear markets occur because there has been a massive misallocation of capital in the preceding period. In an earlier era of capitalism, such bad use of resources tended to occur during periods of war, with the post-conflict period resulting in depression.

In the post WWII era, such periods of capital mis-allocation have mostly been created by central bankers who believed in the myth that low rates create economic growth (Click here to view chart.) It can be seen that all Ursus Magnus episodes have taken place after (or have at least been coincident) with periods of abnormally low rates in the US. This, of course, has been a constant theme of my research over recent years and was a concept that was developed by the great 19th century Swedish economist Knut Wicksell.

When the market rate of interest is kept below the natural rate for a lengthy period, the result tends to be large-scale capital misallocation. And it is this action that leads to Ursus Magnus. Green shading in the chart shows periods when (silly) central bankers kept real short rates in negative territory. It can be seen that an Ursus Magnus never materialized during periods when short rates were positive, but rather after (or during periods) they were left negative for a considerable time.

If this condition is satisfied, the next factor is the length of period that rates were set too low. Since the recent episode of negative real short rates has been significant, the conclusion must be that the creature on the track ahead is starting to growl and is likely an Ursus Magnus.

This bear first started to create mayhem outside of the United States where the misallocation of capital created by the asinine monetary policy of the Federal Reserve was easiest to spot (witness recent events in China, Brazil and much of the commodity and energy production complex). The worry is that this terrifying beast has now moved on to the big developed markets and seems ready to start wreaking havoc. Investors are well advised to take maximum precautions.

OUR LIKES AND DISLIKES.

No changes this week.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.