“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

-GOODHART’S LAW

This week’s EVA is our once-a-month sharing of commentaries from our partners at Gavekal Research. As you will see, this is a “two-fer”: the first written by Gavekal’s founder, Louis Gave, while the second was penned (or keyboarded) by his father, Charles Gave.

Louis’ article, “Peak Hubris”, highlights the escalating confrontation between Big Tech and Big Government. As he points out, some of the world’s largest technology companies are in a position where they can actually influence public attitudes, viewpoints, and possibly even elections.

Unsurprisingly, this makes certain governments—maybe even most—increasingly edgy. In fact, the Wall Street Journal ran a front page article on precisely this subject just two days ago. It described allegations that the “news curators” at Facebook have been suppressing conservative views and elevating those (presumably more liberal) that weren’t popular “trending topics”. (Is it just me or does the term “news curator” give you a creepy Orwellian feeling, as well?)

Similarly, Apple’s refusal to unlock its iPhone for US law enforcement officials has possibly raised eyebrows in Beijing, causing Chinese authorities to “encourage” the sale of domestic smart-phone producers such as Xiaomi or HTC. (Note: the “Occam’s Razor” Louis refers to is the logic rule stating that the simplest hypotheses or explanation is typically the best choice.)

Charles’ piece is on a topic that is near and dear to Evergreen’s philosophical heart: the dangers of passive investing becoming the dominant force in the financial markets. Several past EVAs have pointed out the risks and distortions caused when a benchmark becomes an investment strategy. As we noted years ago, when passive or index-investing was a niche vehicle, it didn’t have much impact on financial markets. Now with trillions either directly or indirectly tracking various benchmarks (most notably the S&P 500), undesirable effects are becoming more significant and frequent.

For example, professional investors seeking to replicate the S&P are forced to hold more of the largest components of that index regardless of valuations. Clearly, this reality amplifies both up- and down-moves, meaning that overpriced areas tend to become more inflated than they would in the past when almost all assets were run by managers who did fundamental analysis. In a similar way, passive investors wind up with less exposure to inexpensive and out-of-favor securities than they would with less of an autopilot-type influence. One could argue this is a key reason why bubbles and busts have become more common over the past 15 years.

The net effect is compromised financial markets that produce a lower rate of return than in “the good old days”. Certainly, the fact that the S&P 500 has returned just 4.3% for the last 16-plus years indicates some validity to that contention. And, as we have noted in prior EVAs, just wait until this calculation is run during the next bear market. When it is, you won’t be hearing about stocks for the long-run—even though that will be precisely the time you should be.

DAVID HAY

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

*The specific securities identified and described do not represent all of the securities purchased, held, or sold for advisory clients, and you should not assume that investments in the securities were or will be profitable. Facebook and Apple are used only to explain recent well publicized events regarding these companies, and these events possible effect on the market in general. HTC and Xiaomi are used only for illustrative purposes. ECM currently holds Apple and may recommend it for client accounts if ECM believes it is suitable investments for the clients, considering various factors such as investment objective and risk tolerance. It may not be suitable for all investors. Certain clients may hold Facebook, HTC and Xiaomi in their accounts, at their discretion; these securities are not recommendations of Evergreen. Please see important disclosures included following this letter.

By Louis Gave

With a few notable exceptions, it’s been a tough few weeks for technology firms; the likes of Microsoft, Intel, Alphabet, TSMC, Sony, Panasonic, Fanuc, Murata and, of course, Apple all released weak earnings and guidance. Behind the disappointments sit different causes, ranging from weak capital spending across Asia (Fanuc), to a less eager Chinese consumer (Apple), to a still prudent Japanese consumer (Sony) and a stronger yen (Murata, Panasonic). Apple is the most interesting case, for not only has it been the last decade’s blow-out success story, but only last summer Chief Executive Tim Cook told CNBC that its China business was growing gangbusters. A few months later it turns out that Apple’s sales are down YoY for the first time since 2003, mostly because of a -26% fall in Chinese iPhone sales. Since overall smartphone sales in China grew 2.5% YoY, the iPhone’s weakness is a head-scratcher. Perhaps it is just a case of the iPhone no longer being this year’s must-have item. Or maybe Apple is simply too pricey compared to the likes of HTC, Xiaomi and Samsung. On the face of it, the latter explanation seems the most likely.**

Interestingly, Apple’s stumbles have occurred just as a number of major tech firms are developing what might be dubbed “peak hubris”. The likes of Facebook, Alphabet, Apple and Amazon increasingly enjoy monopolistic-like franchises: an Apple IOS user is unlikely to switch to Windows once all of his or her music, photos and movies are on the Apple platform. Similarly, a company which relies on Google advertising for website traffic is unlikely to change provider. Indeed, looking at these tech firms’ dominant positions, it is hard to escape the conclusion that they should be able to lock in a sustainable rent that will only be taken away by a) a genuine technological leap or b) a full-frontal government attack (similar to Teddy Roosevelt’s anti-trust activity).**

Such an underlying reality begs the question of why such behemoths have seemingly gone out of their way in recent months to wind up governments. From Alphabet’s aggressive tax optimization strategies, to Apple’s refusal to unlock the San Bernardino terrorist’s phone, to Amazon’s aggressive pursuit of drone delivery strategies, it seems that the tech titans are telling governments—the only distributor of legal violence in the system—that they are strong, and do not need to kowtow.

And this may be true. After all, through their control of news-flow, the influence of “Big Tech” now exceeds that ever achieved by the newspaper barons. So perhaps Big Tech is right to stand up to governments and has nothing to fear. Or perhaps the coming years will show that, instead of being smart, Big Tech was simply being hubristic; that paying a higher tax rate (and maintaining a monopolistic situation) would have been smarter than facing anti-trust lawsuits. That complying (quietly) with a (perhaps legally dubious) order from the Federal Bureau of Investigation might have made more sense than creating bad blood and a desire for payback within the federal law enforcement community.

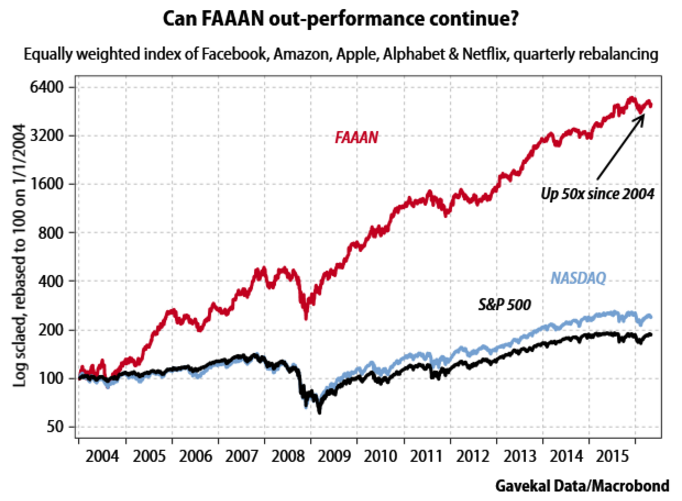

At stake is the question of whether governments everywhere remain jealous of their power, and will take down corporates which are perceived to stand in the way (as they have in the past), or whether we are entering into a new era where Big Tech, given its global reach, turns out to be more powerful than “Big Government”. Beyond the disappointing earnings rests a simple question: is there now a “political risk” for investors in Big Tech that wasn’t there in the massive FAAAN performance of the past decade.

Which brings us back to Apple’s disappointing Chinese sales. While six months ago, Apple’s CEO was bragging about the growth of his China smartphone business, that business seems to have gone off a cliff. Such a sudden deterioration can be read in different ways. Occam’s razor would indicate that, given other manufacturers’ decent sales (most notably Samsung’s), Apple’s disappointing Chinese performance reflects an “out of date” product selling at the wrong price point. That remains the most logical explanation. Still, we also have to acknowledge that, in China, most people buy a phone through monthly payment plans offered by one of the big three state controlled telecom operators (China Mobile, China Unicom and China Telecom**). Apple’s sudden sales decline does beg the question whether these operators have stopped pushing Apple products quite as aggressively as they did previously. After all, if Apple won’t open the phone of a known terrorist for the US government, what are the odds that it will accede to a similar request by the Beijing politburo for the phone of a Chinese political dissident. For the Chinese Public Security Bureau, the one conclusion to draw from recent months is perhaps that it is better that every Chinese person be on a Xiaomi or HTC, than on an iPhone.

By Charles Gave

It is astonishing the number of articles one can read all claiming to “show” that passive investments consistently outperform active money managers. Their conclusion is always the same: savers should invest in indexes or tracker funds rather than actively-managed funds, and that as a result they will be much better off. This claim has been repeated so often it has become received wisdom. Alas, in this case, as in so many others, the received wisdom fails to stand up to rigorous analysis. In the long run, passive investment makes everyone very much worse off.

When I was a student at the University of Toulouse some 50 years ago, I took a number of classes on something that bothered my professor a great deal: that an action which is perfectly rational at the level of the individual can lead to catastrophe at the macro level. This is what logicians call the fallacy of composition. The classic example is what happens when depositors take their cash out of the bank because they are worried it will fail. At the level of each individual, the decision makes perfect sense. But if everyone does it, the result is calamitous.

The same applies to indexing, but almost no one seems to understand what is going on. Capitalism fosters economic growth through the process of creative destruction. Businesses which have a high return on invested capital get access to capital; those that do not, starve and die in a ruthlessly Darwinian process. For active money managers, the name of the game is to buy the first lot and to sell the rest. Getting this right is an extraordinarily difficult job, which leads to a wide range of results—just as in the real world of production. However, this process of trial and error allows the market to determine who is talented at choosing between good and bad investments. In time, these talented types will grow too big and become less efficient, and new contenders will emerge to challenge the bloated old Tyrannosaurus rex.

So, in a normal competitive world the wide dispersion of results in the active money management industry is a sign that capital is being allocated efficiently, because the goal is to allocate it according to the ROIC, and not in line with what the competition is doing.

But a world in which risk is defined as the divergence in investment returns relative to an index looks very different. As a money manager in such a world, your only goal will be to minimize your deviation from the benchmark. You will pay no attention to the ROIC of the underlying companies in your portfolio, and you will allocate capital solely according to the size of companies’ market capitalization.

In this world, the dispersion of results will be very small. What’s more since the allocation of new capital will be determined by what amounts to a socialist measure of risk, the growth rate of the economy will go down, and therefore so will returns in the stock market. As a result, over the long run even the laggards among active managers in a competitive world will tend to generate higher absolute returns than the best passive managers under the socialist system of indexation.

Why do I call passive investment a form of socialism? Quite simply because the target is equality of outcome, without any consideration of what effect this goal will have on growth. Sadly, even at the core of the capitalist system, ideas that favor equality of outcome over equality of opportunity increasingly prevail.

It is not just the capital markets which are so afflicted. Our schools and colleges too are moving more and more towards equality of outcome. As a result, our educational system has become what one well-known teacher in France described a few years ago in a best-selling book as “La Fabrique Du Cretin”*. Just as standards of education collapse if all students are awarded AAA grades, so if all money managers get the same results, economic growth collapses. As Aristotle observed: the same cause produces the same effect.

So when people ask me how to assess a manager I always give the same answer. There are three levels of profitability in the capitalist system:

• 1% real return if you take no risk (three-month T-bills)

• 3% real return if you take only duration risk (government bonds)

• 6% real return if you are prepared to risk complete loss of capital (equities)

Choose your level of risk and assess your manager over five years.

When I used to manage money myself, I more or less aimed for a return of 4.5% with a 3% risk (not that I succeeded all the time). And when anyone asked me which index I wanted to be measured against, I always answered, “You choose. I will pay no attention”. The consultants did not like me one little bit.

If we want capitalism to return to its roots, we should decide once and for all that risk is defined as losing money, not deviation from a benchmark. Indexation will take us all to the poorhouse.

*Essentially in English, The Idiot Factory.

**The specific securities identified and described do not represent all of the securities purchased, held, or sold for advisory clients, and you should not assume that investments in the securities were or will be profitable. Microsoft, Intel, Alphabet, TSMC, Sony, Panasonic, Fanuc, Murata, Apple, HTC, Xiaomi, Samsung, Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, China Mobile, China, Telecom are used only to illustrate and explain recent well publicized events and releases. ECM currently holds Microsoft, Apple, Intel, Alphabet, Panasonic, Hitachi and Fanuc and may recommend them for client accounts if ECM believes it is suitable investments for the clients, considering various factors such as investment objective and risk tolerance. They may not be suitable for all investors. Certain clients may hold TSMC, Sony, Murata, HTC, Xiaomi, China Mobile, China Unicom and China Telecom in their accounts, at their discretion; these securities are not recommendations of Evergreen. Please see important disclosures included following this letter.

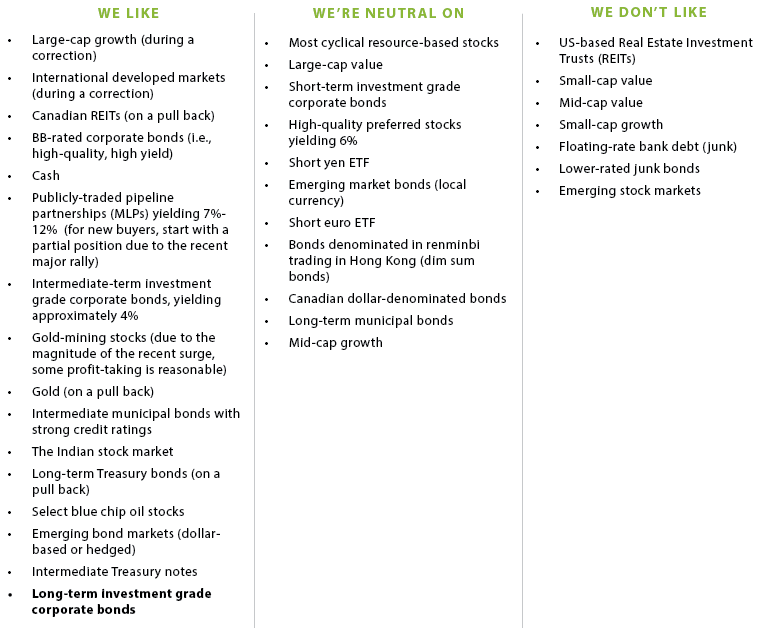

OUR LIKES/DISLIKES

Changes are bolded below.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.