“One way to make sure crime doesn’t pay would be to let the government run it.”

-RONALD REAGAN

-This Labor Day is bringing back haunting memories of the same holiday weekend eight years ago.

-Back then, former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson made the decision to place Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in “conservatorship”. In other words, they were bust and shareholders—including those owning preferred stock—were wiped out.

-A panic started almost instantly. Shortly thereafter, Lehman collapsed, Washington Mutual failed, AIG needed a bail-out, and the Primary Reserve money market fund “broke the buck”.

-New mark-to-market accounting rules forced banks and insurance companies to value their portfolios at prevailing panic-driven prices. This created a self-fulfilling “doom loop”. Even the strongest banks and insurance companies might have been technically insolvent as markets continued to crumble.

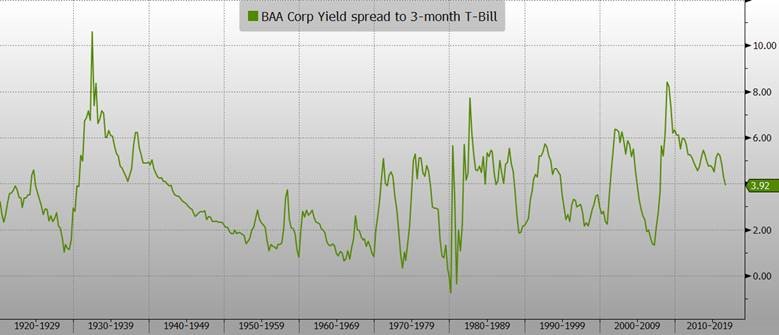

-AAA-rated mortgage pools were trading at 30% of face value. High-grade corporate bonds dove to 60 to 70 cents on the dollar. Credit spreads (the yield gap between government and corporate bonds) erupted to the highest since the Great Depression.

-In response to the escalating disaster, the Treasury Dept pushed through the $700 billion financial system bail-out known as TARP and the Fed guaranteed all money-market fund assets. Despite these measures, the panic continued.

-At the time, my view was the ultimate problem was collapsing asset prices. This caused me to write a letter imploring the Fed/Treasury to do a “shock and awe” purchase of high-grade corporate bonds and preferred stocks, as well as non-government-backed mortgages at bombed-out prices. Eventually, this proposal made it to the desk of the San Francisco Fed president.

-The government could have borrowed at 1% and reinvested at high-single to low-double digit yields, creating a taxpayer windfall and tremendously boosting confidence. Instead, the Fed “printed” $1 trillion and bought the most overpriced asset in the world, US treasuries. This began the now notorious Quantitative Easing (QE) process.

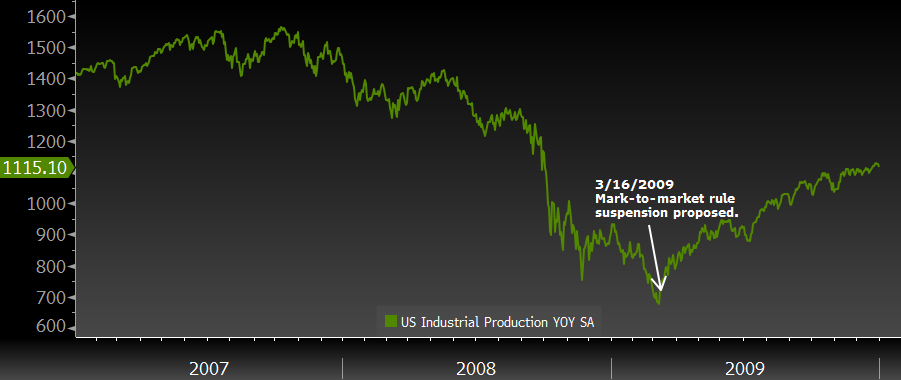

-QE 1.0 still didn’t turn the tide as it stoked fears of rampant inflation, paralyzing investors. Asset prices continued to fall. The global economy careened into the worst downturn since the Great Depression. It wasn’t until a proposal was floated in March of 2009 to suspend the mark-to-market rule that the 60% decline in the S&P 500 ended and the bull market began its long run.

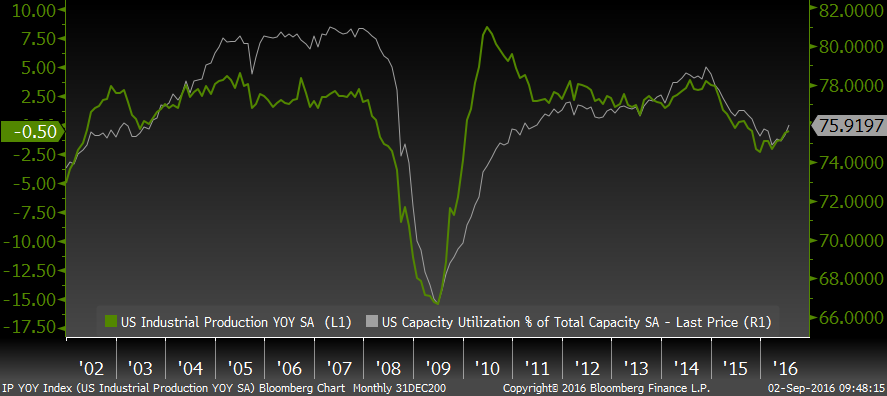

-Now, eight years later, central banks have resorted to ever more extreme and exotic ploys to keep asset prices high and, supposedly, restore normal economic growth. However, the US continues to experience the weakest expansion in modern history and most other “rich” economies are even more sluggish.

-A media frenzy surrounds every Fed meeting as it agonizes over the smallest of rate increases. Yet there is almost no consideration given to shrinking its bloated balance sheet. Consequently, the Fed, with its key interest rate near zero, has limited stimulus options during the next market panic and/or recession.

Thermonuclear blast from the past. Ah, Labor Day weekend! The end of summer, the beginning of football season and, for so many, the start of school for themselves or their loved ones. Maybe, like me, you view this transition time with mixed emotions. It’s always tough, especially in Seattle, to say farewell to summer, even if it was a less than stellar one in the Pacific Northwest. But another feeling has been coming over me lately as I recall a Labor Day eight years ago.

It was over Labor Day weekend in 2008 that rumors began spreading about Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac being on the verge of failure. A few days later, on September 6th, 2008—another day that will live in infamy—the once proud and powerful GSEs* entered US government conservatorship. In other words, they were bust.

Mere months earlier, the Federal government had encouraged the country’s community banks to load up on preferred stock from the two entities (who I referred to at the time as Fannie Mayhem and Freddie Macabre). Rather than protect these trusting investors from the de facto bankruptcy, Hank Paulson’s Treasury department opted to wipe them out along with, more justifiably, all equity shareholders.

But instead of reassuring markets, this action set off a chain reaction of utter panic. Credit spreads exploded upward to a degree not seen since the worst days of the Great Depression. As result, Corporate America’s borrowing costs were soaring at the same time that profits were tumbling.

BBB-RATED CORPORATE BOND YIELDS VERSUS T-FILL YIELDS

Source: Evergreen Gavekal, Bloomberg

Even worse, recently enacted “mark-to-market” accounting rules forced financial institutions to value their securities at prevailing prices. Hedge funds smelled blood in the water and began shorting bank stocks and bonds, further feeding the panic.

Simultaneously, the mortgage market was in utter disarray. The market values of AAA-rated pools of mortgage securities had been cut in half by October of that year. Banks, it soon was revealed, held hundreds of billions of these presumed bullet-proof assets. Greatly adding to the rapidly escalating chaos, insurance giant AIG disclosed that it had essentially assumed the liability for $500 billion of credit default swaps (CDSs, instruments that effectively insure against defaults).

In return for collecting a modest premium, akin to receiving interest on the underlying securities, AIG was on the hook to a degree that threatened to crash a company that only months before had a market valuation of $200 billion and employed 117,000 people. Although AIG’s mortgage exposure was nearly all AAA-rated, it included roughly $80 billion of the now-infamous sub-prime collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). These had almost inexplicably been bestowed with the highest possible credit rating from Moody’s and S&P because the underlying skanky mortgages had been sliced and diced into different “tranches” or levels.

The riskiest took the first losses and then any further hits would eat their way up the rating tiers. It became quickly apparent that the housing market was imploding to a degree that threatened the investment grade slices. Fear mounted to the point that even the most protected tranches—the AAA—were considered to be at risk of deep losses. (The above scenario is basically what the book and film The Big Short was all about.)

Accordingly, the global financial system was fully engulfed in what could be rightly called “A Doom Loop”, and it was getting “doomier” by the day.

The sum of all fears. It was during this terrifying time that the words of novelist Frank Herbert in his Sci-Fi classic, “Dune”, started repeatedly reverberating in my mind: “Fear is the mind blocker”. The fear became so irrational that the aforementioned AAA-rated securities kept skidding all the way down to 30 cents on the dollar, despite the reality that there was almost no chance most of them would incur more than roughly 10% of ultimate losses. Because these instruments were held throughout the financial system—not just in the US, but around the world—their price collapse was a devastating blow, made exponentially worse by the new mark-to-market rules described above.

To make matters worse, which they definitely didn’t need to be, the corporate bond market had also seized up. Investment-grade issues were routinely trading 30% to 40% below par and normally non-volatile preferred stocks were hit harder yet. This price implosion is why credit spreads were quickly approaching Great Depression levels. Once again, banks and insurance companies were now forced to value them at these nonsensical prices.

In short order, Lehman Brothers collapsed, wiping out all common stock, preferred, and debt holders (eventually, there would be some recovery for the bond owners). Then, Seattle-based Washington Mutual, the nation’s largest savings bank, was seized by the FDIC and sold for a pittance in the dead of night to JP Morgan, once more wiping out all equity and debt owners.

Meanwhile, Hank Paulson and other senior government finance officials belatedly realized that their policy of letting some of the world’s largest financial institutions go down the tubes was, to say the least, not working as planned. Mr. Paulson began furiously exhorting Congress to pass what would eventually become known as the Troubled Asset Relief Plan (TARP), in order to inject federal government funding into the financial system.

When Congress balked at providing Mr. Paulson the $700 billion for the TARP he was requesting, the stock market, which was attempting to stabilize, crashed again. Banking Goliath Citigroup was rumored to be the next to fail as its stock price was making a bee-line for $1. It became obvious to all—save for the most ardent “let the rot be purged” types—that extreme rescue measures were needed.

Faced with global markets consumed by intensifying panic, Congress reluctantly agreed to the TARP and, in the process, AIG was thrown a life-line, albeit an exceedingly costly one—at least for stockholders who were essentially once more obliterated. The government took as its ton pound of flesh 90% of the equity under the reasoning that if it had not stepped in shareholders—and bondholders—would both have been wiped out. Clearly, AIG was too big to fail, even though it was also almost too big to bail (consuming about 20% of TARP’s total resources).

Some felt that this rescue—combined with the rest of the $550 billion TARP funds injected into banks, insurance companies, and, oddly, automakers like GM—was enough to turn back the tides of panic. But it was not to be…

Fed frenzy. As the Treasury was working feverishly to push through TARP** and save AIG, the Fed was fast running out of bullets. It had cut interest rates repeatedly starting in the summer of 2007 when the housing bust became so obvious that even Ben Bernanke realized the problems were anything but contained. By October, the Fed’s overnight rate was down to 1%. Nevertheless, financial markets continued to tank.

To its credit, once the Fed realized the severity of the crisis, it began to take bold and innovative measures. One of the most important was guaranteeing the assets in money market funds which were beginning to experience a 1930s-style bank run, in the wake of the Primary Reserve fund “breaking the buck” (meaning investors were incurring a loss on a supposedly risk-free fund).

But neither the Fed nor the Treasury seemed to have a clue about how to deal with the overarching threat to the global financial system: collapsing asset prices. The way things were trending not even JP Morgan nor Wells Fargo might have been able to withstand having to mark their mortgage and bond portfolios to market in the midst of the greatest forced liquidation since 1929. As many noted at the time, it was effectively a worldwide margin call that was feeding on itself as lower prices produced a cascading amount of involuntary selling. (You’ve got to admit, you’ve forgotten how horrifying those days truly were!)

From my vantage as the Chief Investment Officer of Evergreen Capital (as we were known then), I was torn between outrage over how the Fed had allowed this to happen, a sense of complete helplessness as I watched high-quality assets vaporize in price, and an intense desire to buy almost everything in sight, especially income securities. Many of the latter were yielding in the teens and in some cases over 20%. It was my first encounter with what Warren Buffett said he experienced at the depths of the 1974 epic bear market when he stated he felt like an oversexed guy in a bordello (the Oracle of Omaha was a bit less politically correct back in the ‘70s).

My Fed fury was due to its sheer blindness about the magnitude of the housing bubble that had inflated as a result of interest rates it had kept too low, for too long, as well as the blind-eye it turned to outrageously lax lending practices. (Incredibly, Alan Greenspan had actually encouraged home buyers to take out adjustable rate mortgages which further destabilized the market as the teaser-rate periods expired.) And the Federal government itself had put enormous pressure on the mortgage industry to extend sub-prime credits. Now, I was equally furious that neither the Fed nor the government had a plan to deal with the continuing collapse in almost every asset price on the planet.

In my mind, there was no doubt what needed to be done and it centered on arguably the most important clearing house of all: the corporate credit markets. Partially to vent my frustration and partially to just take some kind of action, I drafted a most unusual letter, one that I had totally forgotten about until I stumbled on it a few weeks ago. Here’s what I wrote (for those wanting a speed-read just check out the text in blue):

October 17, 2008

Dear Senator :

This letter is being sent to you due to the current crisis in the financial market which is now rapidly infecting the real economy.

While both the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury department have recently initiated much needed actions to stabilize the banking system, it is clear that far more aggressive intervention is necessary, similar to what the Fed recently did in the commercial paper market. By directly acquiring commercial paper from corporations a complete and unimaginable liquidity crisis was averted; the Fed deserves great credit for this intelligent intervention.

However, the extreme stress in the corporate bond market, with yields on BBB-rated issues at levels not seen since the Great Depression, necessitates that the Fed moves beyond merely purchasing commercial paper—it needs to aggressively acquire longer term investment grade bonds as well as preferred stocks in the open market. And it needs to do so in whatever quantity is necessary to bring yields down to more normal levels.

This is in effect what the Treasury is preparing to do with the Troubled Asset Relief Program but would be much simpler and inherently safer for taxpayers. In fact, it would be virtually guaranteed to generate immediate and, eventually, significant profits for taxpayers.

The math is straightforward: the government can borrow in the short-term debt markets at rates around 2%. The average high-grade corporate bond is trading at 87 cents on the dollar and yields 8.5%, reflecting the extremely depressed state of the non-government fixed income markets. Just since Labor Day, high grade corporate bonds have declined an astounding 20%. According to The Wall Street Journal, investment grade corporate debt has not offered such high returns since the 1980s. Amazingly, this yield spike has occurred at a time of rapidly falling commodity prices and inflation, as well as during a time of collapsing risk-free interest rates. Thus, it’s unquestionable that both unbridled fear and forced liquidation are totally overwhelming fundamentals.

Prices are even more distressed in the market for preferred stocks; many investment grade issues trade at 60% of par value with yields approaching 12%. Consequently, Fed purchases of these securities would be even more lucrative for taxpayers.

Barring forceful intervention, further price declines are probable and could possibly accelerate. The implications of the credit markets collapsing are even more ominous than are those of the recent stock market plunge: as the cost of capital soars and buyers evaporate, even at exceedingly elevated yields, long-term financing for corporate America is essentially impossible. Just as destabilizing, financial institutions, including traditional insurance companies that did not participate in esoteric activities such as buying sub-prime CDOs and selling Credit Default Swaps, are now also under extreme pressure as their conservative portfolios plummet in value. This raises the specter of further rating downgrades and even more forced liquidation of bonds and preferred stocks.

Amplifying this disaster is the fact that myriad closed-end mutual funds own these securities with some degree of leverage. The breathtaking decline in the value of yield securities is endangering their debt coverage ratios, precipitating even more forced liquidation, effectively setting off a self-perpetuating cycle of margin calls. There is no doubt the situation is precarious in the extreme but it is definitely not hopeless.

This is one of those rare times when the Federal government can enjoy a high rate of return while at the same time producing an extraordinary societal benefit. Not only will it earn a fat spread between its cost of capital and lofty yields, the Fed and/or Treasury would be almost certain to realize substantial capital gains by investing large sums at irrationally depressed prices. Equally likely, once there is a bidder in the credit markets with unlimited resources preventing further absurd prices declines, and thereby driving prices back up, the astronomical sums of private money on the sidelines will be emboldened to join in the buying spree. Thus, an utter disaster can become, nearly overnight, a stunning victory.

By combining this effort with an equally aggressive plan to facilitate and ensure inter-bank lending, as the Fed is currently working hard to ensure, the overall financial system will receive a mammoth boost of confidence. We have unquestionably entered that stage of this credit cataclysm where fear, unless radically attacked and defeated, is now in the driver’s seat. Our government needs to commit all of its resources, and to do so at the points of maximum stress, in order to arrest this terrifying spiral of falling asset prices.

I respectfully request that you submit this proposal to the Senate Finance Committee at your earliest convenience.

Yours truly,

My letter, written in mid-October, 2008, managed to make it into some mainstream media outlets, giving me, as I noted in the 10/17/08 EVA, my Andy Warhol moment. (To read that EVA, please click on this link.) However, if I was hoping for some encouragement or concurrence, I was soon to be disappointed.

Coulda, shoulda. Admittedly, what I was proposing back then—essentially a $1 trillion purchase blitz by the Fed/Treasury, targeting high quality US yield instruments (private sector not government—was a most radical recommendation. But my logic was that desperate times necessitated desperate measures. Judging by the flame mails I received in reaction to it—calling me a socialist, a free-enterprise apostate, and a disbeliever in efficient markets (as I wrote at the time, guilty as charged on that last one)—I hadn’t exactly knocked it out of the park.

However, thanks to someone I met at a presentation I had given a week or so earlier (at which I made my case that you could throw a dart at the markets and make money—if you had the courage to throw the dart), my letter wound up on the desk of the president of the San Francisco Fed. At the time, it was headed by a relatively obscure Fed official named Janet Yellen. Supposedly (heavy emphasis on “supposedly”), she was intrigued by the idea and asked through our mutual connection how a corporate bond buying campaign might occur. At the speed of light in a vacuum, I replied that the Fed (or the Treasury acting in its place) could simply buy LQD, essentially an index fund of investment-grade corporate bonds. Moreover, I noted the government could do this in a non-inflationary way by selling T-bills at yields close to zero to fund the purchases. If the Fed had actually pulled the trigger, it would have been one of the greatest carry trades*** of all time.

Moreover, as I stated in my letter, if the government had come in with that kind of firepower, to buy securities priced at Great Depression levels, it would have undoubtedly catalyzed a buying stampede. Enormous sums of cash had accumulated as investors were selling everything en masse. These trillions were earning next to nothing and primed to move back into stocks and bonds once confidence was restored.

Of course, this proposal went nowhere. However, the Fed did adopt the trillion dollar shock and awe concept (no thanks to me, I’m sure). Unfortunately, it did two things that were less than reassuring.

First, the Fed simply created the money out of their digital printing press. This unnerved investors globally who felt this would generate inflation, possibly even of the hyper variety, making them reluctant to buy stocks or bonds. Second, the Fed used their first round of what became known as Quantitative Easing (the now infamous QE) to buy the most overpriced debt securities on the planet: US treasuries and government-backed mortgages. Consequently, the result was a lot more heat than light.

In fact, TARP was passed on October 3rd, 2008, and QE 1 was launched in early December of that year. Yet, stocks and corporate bonds (not to mention REITs, MLPs, commodities, and almost everything else) kept circling toward earth like a mortally wounded fighter plane until early March of 2009. Fascinatingly, it was just a few days after the S&P’s “satanic” low of 666 on March 9th that the FASB accounting standards board proposed suspending its havoc-wreaking mark-to-market rule. Coincidentally or not (I think not), it was at that point the bull market, which we are still enjoying eight years later, began its explosive lift off.

GOOD-BYE FASB 157, HELLO BULL MARKET!

Source: Evergreen Gavekal, Bloomberg

Therefore, despite cutting rates to the lowest point ever, as well as implementing TARP, QE I, and massive fiscal stimulus, what could have been a brutal, but brief, market panic (like 1987) morphed into the economic cataclysm now referred to as the Great Recession. And much that has happened since then simply must recall that memorable Chinese proverb: “What the wise man does in the beginning, the fool does at the end.”

Yellen but definitely not gellin’. So, here we are eight years after that momentous Labor Day weekend in 2008. What do we really have to show for some $25 trillion globally of central bank fabricated money and a doubling of the US national debt? How about the worst economic expansion of modern times? This is despite the fact that some central banks have now resorted to directly buying common stocks with their money-from-nothing (the once-staid Swiss National Bank now owns $60 billion of US stocks).

It is also notwithstanding the reality that these “large scale asset purchases” are generating increasingly diminishing returns—not to mention extreme distress for pension plans, insurance companies, banks, and the hundreds of millions of baby boomers around the world who are hoping to someday retire without living under the nearest bridge. It’s one thing to buy stocks or bonds during a total panic, and at rock-bottom prices, as a temporary measure to stem the selling frenzy. It’s completely different, however, to continue the buying binge as US stocks sell at their highest median price-to-sales ratio ever and as one-half of the developed world’s bonds now trade at negative yields (as noted in prior EVAs, out to nearly 50 years in the Swiss debt market). Further, as a shock to almost everyone, their money fabrication has created low-flation, even deflation, in consumer and producer prices.

Now here we are again with the latest Fed meeting looming and another high-anxiety drama as to whether it will hike rates all the way to—gasp!—0.56%. The media circus around these events is simply absurd.

Even by the Fed’s own latest and downwardly revised calculations, its overnight rate should be at 3% under normal circumstances—like when the unemployment rate is around 5% and inflation is close to 2%. Oh, yeah, sort of like what we have right now! Do you really think there is any chance they will get close to that during this economic cycle (which is already rolling over)?

US INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION AND CAPACITY UTILIZATION PEAKED IN 2014

Source: Evergreen Gavekal, Bloomberg

It’s almost a sure bet that even if they got half way there the dollar would go ballistic and financial markets would freak out. The up-beat news for market bulls (ignoring the long-term cost of further delaying rate normalization) is that it’s about as likely to happen as Anthony Weiner is to get a Father of the Year nomination. These people at the Fed are so afraid of their own shadow, if they were groundhogs winter would never be over!

Yet, there is something it could do that would likely be far less destabilizing (yes, I know, here I go again). The Fed’s balance sheet is currently so bloated that it makes a Sumo wrestler look svelte. If you think I’m exaggerating it presently totals $4.5 trillion up from $700 billion pre-crisis, all acquired with funny money. Why not simply let it gradually roll off instead of being continually reinvested as the Fed is doing now? Allow the mortgages it holds to pay down and its vast trove of short-term treasuries to mature, using the proceeds to slowly cancel some of that $3.8 trillion of fallow reserves in the banking system. But there is almost no one seriously discussing this scenario. Consequently, the Fed is left with very little ability to cope with the next panic, save our lonely belief it will finally begin buying corporate bonds (as the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, and the Bank of England are already doing—at ridiculously low yields, by the way).

To close, I’d like to relay an excerpt from a speech Janet Yellen recently gave at the Fed’s annual symposium in Jackson Hole. “For example, if future policymakers responded to a severe recession by announcing their intention to keep the federal funds rate near zero for a very long time after the economy had substantially recovered…then they might inadvertently encourage excessive risk-taking and so undermine financial stability.” Is she serious? There should have been a laugh-track playing after this line. “For example”? “Future”? “Inadvertently encourage excessive risk-taking”? As anyone this side of Outer Mongolia knows, that is precisely what this Fed has done.

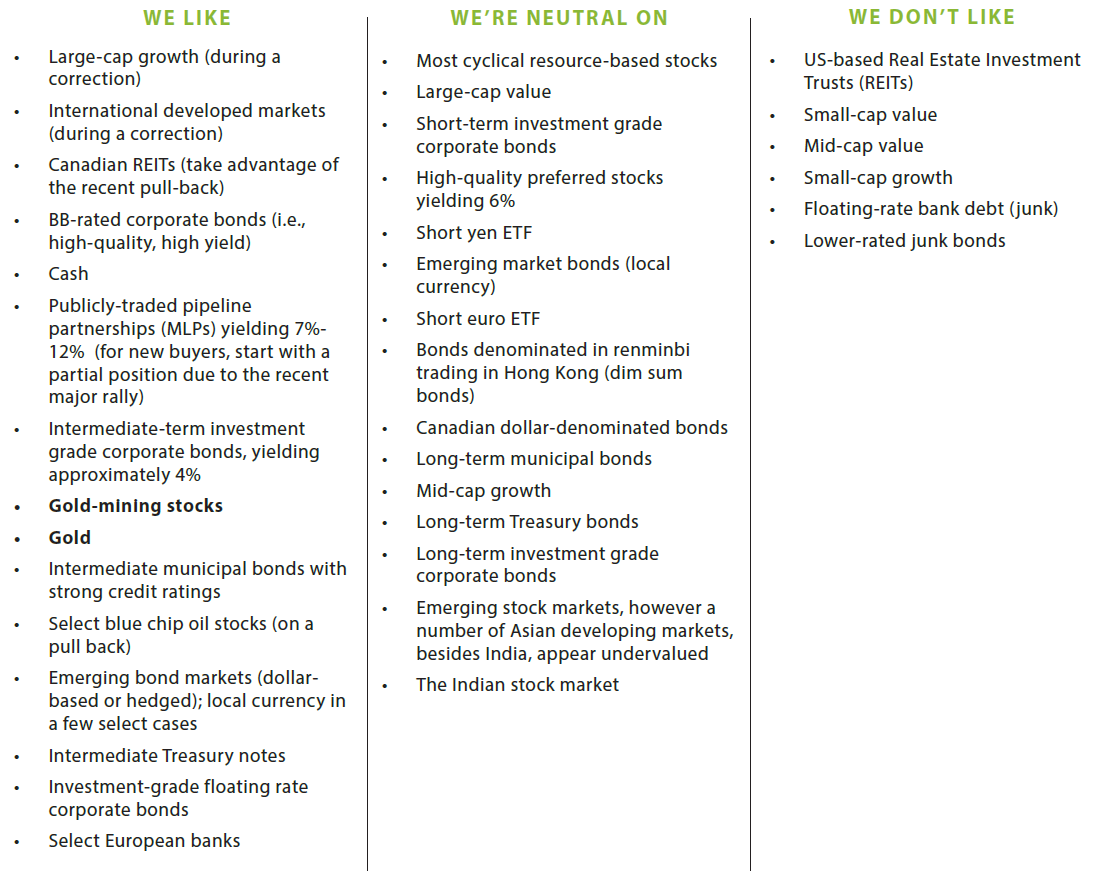

Because Evergreen doesn’t see the Fed drastically altering its current modus operandi, we are likely to be stuck in what former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers calls secular stagnation with rates going even lower, at least in the US, during the next recession and/or market panic. Moreover, we also believe that is when the Fed will step in and—finally—buy US corporate bonds, driving their yields down to the miniscule levels seen in Europe, the UK, and Japan. Accordingly, this is why Evergreen continues to acquire longer-term US yield instruments with yields in the 5%, or higher, range. Those kinds of returns, good reader, are likely to go the way of the Dodo bird before this current set of Fed policies becomes extinct.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

*Government-sponsored entities.

**Evergreen, by the way, was one of the few voices out there saying back in 2008 that the government would make money on TARP, a view which brought us serious derision. Ex-Treasury Secretary Paulson gets kudos for receiving warrants in return for the bailout funds, eventually rendering the TARP a significant money-maker for taxpayers.

***A carry trade is where the interest rate on money borrowed to make an investment is less than what it earns, creating a built-in profit (theoretically) for the investor.

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

Note changes in bold.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.