“Never think that lack of variability is stability. Don’t confuse lack of volatility with stability, ever.”

- Nassim Nicholas Taleb

CALM BEFORE THE VOLATILITY STORM?

Tyler Hay

I wrote this edition of the Evergreen Virtual Advisor (EVA) from my hotel room in Laguna Beach, California, looking out at the serene Pacific Ocean. The setting seemed very appropriate considering the soothing comments I heard a few nights ago at Schwab’s EXPLORE conference from Liz Ann Sonder, Chief Investment Strategist. Ever since the stormy summer of 2011, US stock market investors have been riding a gentle but persistent wave that has carried them to the ultimate financial promised land of high returns and low volatility.

To Sonder’s credit, she has been consistently bullish since the recovery started in 2009 and, as stated above, she remains generally quite optimistic. She believes this market is taking a breather only to head higher. Her fundamental point was that you can’t be in the final stages of a bull market without investor sentiment hitting a state of euphoria. As readers know, our outlook is more cautious. Even in secular bull markets there can be significant market declines, especially when investor psyche becomes complacent, even if not euphoric. But instead of another analysis as to where we might be in this market cycle, I wanted to pivot the conversation to something I find more interesting and relevant.

It is my opinion that we have entered a new era of volatility. This is not a bad thing for investors. In fact, skilled investors embrace volatility. For investors who take the truly passive approach, it will likely be a more extreme roller coaster ride of higher highs and lower lows (as investors in the Guggenheim Solar ETF just found out when it lost 7% in one day). I am simply reinforcing what you already know—markets are cyclical. J.P. Morgan was right when, a century or more ago, he said that stocks will fluctuate. So my point isn’t exactly a divine revelation, but I am suggesting that two key developments have occurred in recent history which have forever changed the dynamics of financial markets.

The first game-changer was the rise of the Internet. I’m not talking about the emergence of new technology companies. Instead, I’m focused on how the Internet has altered market accessibility and the subsequent ease with which individuals can speculate invest. Second, exchange traded funds (ETFs) have emerged as the most dominant financial instrument of the 21st century. Their parabolic growth has been stunning but it’s how they’ve evolved since their infancy that’s changed the way capital markets behave. Combined, these two forces have shifted how market participants act and how financial markets function.

Let’s turn back the clock. Investing used to be extremely cumbersome and reserved for a select few who had men with big cigars and pin stripe suits calling to “broker” them stocks. Company research was nearly impossible to find for the layperson. It was proprietary and closely-held by Wall Street firms who sought to use it to lure clients back and forth between themselves and other brokerage houses. Trades were expensive and the array of investments available was microscopic compared to today.

The emergence of the Internet and related technology has democratized information. It’s become both cheaper and easier for investors to participate. A smartphone and a few hundred dollars are all you need to get started these days! A recent article MarketWatch discussed the astounding rate of growth for investors who place trades using mobile devices. Charles Schwab, TD Ameritrade, and Fidelity are all estimating that 10% of their trading volume is occurring from smartphones and it’s growing between 60-80% annually.

Beyond basic accessibility, technology has helped level the playing field in other ways. The Internet has made it easier for all investors to perform due diligence on companies, economies, people, etc. Trading costs have been driven way down because technology has made it easier for brokers to execute transactions on clients’ behalf. Online websites and blogs have sprung up offering cheap investment guidance for those willing to spend the time. Which brings me to my next and important point.

The Internet hasn’t simply enabled new investors to participate, it’s also empowered people to go it on their own. DIY, which stands for “do-it-yourself”, has become a massive trend. Recently, a colleague and I visited some clients who bought a condo in southern California that needed to be remodeled. Instead of hiring a contractor, these two brave souls decided to test their limits (and their marriage) and do the entire project themselves. I’m not talking wallpaper and carpet. I’m talking new walls, rerouting plumbing, moving electric wiring, replacing entire kitchen cabinets. It was comprehensive to say the least. While they are handy people by nature, many of the tasks they performed were new to them. Bewildered, since I’m the second least handy person in the world (after my father), I asked how they learned to do all this on their own. The answer was embarrassingly simple: “Google.”

As easy as the Internet has made it to do things like remodel your condo, it has made it even easier to invest. However, it’s also never been easier to destroy, in a short period of time, what took a lifetime to build. Information doesn’t mean knowledge or skill. Handing me a cookbook doesn’t make me a chef. The Internet has obscured the delineation between information and insights and it’s one huge reason increased volatility is here to stay. Retail investors are notoriously fickle and trend-following. As they have gained easier access to trading and “knowledge”, these tendencies are now allowed to play out without the gating factor of professional counsel. Despite the many flaws of the old stockbroker model, there was real value provided when a seasoned and conscientious financial adviser prevented his or her clients from knee-jerk decision making—typically frenzied buying at high prices and despondent selling during bear markets.

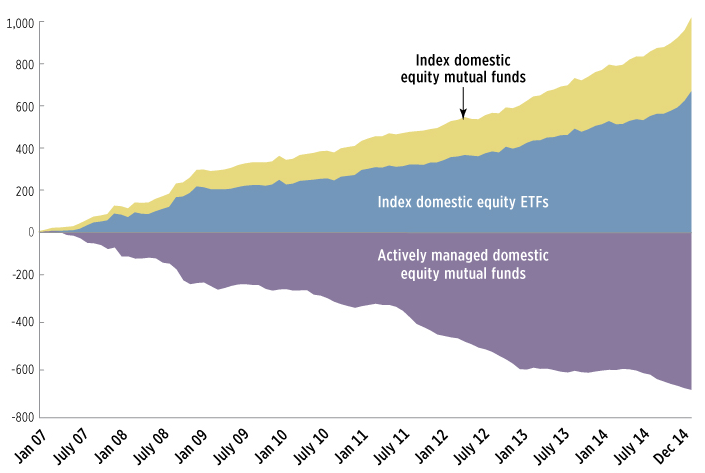

Besides the Internet turning literally anyone with a smartphone and broadband connection into a potential investor, there’s another powerful force that has emerged: ETFs. They are arguably the most dominant investment trend in financial markets over the last fifteen years. The chart below illustrates the massive blow they’ve dealt to the actively managed mutual fund space.

FIGURE 1: CUMULATIVE FLOWS TO AND NET SHARE ISSUANCE EQUITY MUTUAL FUNDS AND INDEX ETF Source: 2015 Investment Company Fact Book

Source: 2015 Investment Company Fact Book

A recent survey found that 51% of firms now use ETFs to build portfolios for their clients. Another discovered that 64% of investors plan on continuing to increase their ETF exposure. In 2003, there were 10 ETFs at the start of the year. By year-end of 2003 there were 119. At the end of 2014 there were 1,411.

Originally, ETFs served a very constructive purpose as they gave investors a diversified, low cost, and highly tax-efficient exposure to a broad portion of the financial markets. It’s no secret that Wall Street believes you can never have too much of a good thing. Thus, it began to create niche ETFs that offered participation in much narrower and esoteric investment themes. Now you can buy an ETF that gives you exposure to options, futures, junk bonds, and various other dangerous market segments. Most people, individuals and professionals, still associate ETFs with very safe ways to invest broadly at a low fee. This is no longer a proper understanding of the ETF space.

Let me use another cooking analogy. Thomas Keller is considered one of the finest chefs in the world and I’m far from it. If you gave us both a can of peanut butter, a jar of jelly, and some sliced bread to prepare a sandwich, the outcome might be pretty similar. Now if you turned us loose in Whole Foods and asked us to prepare dinner, the end results would be galaxies apart.

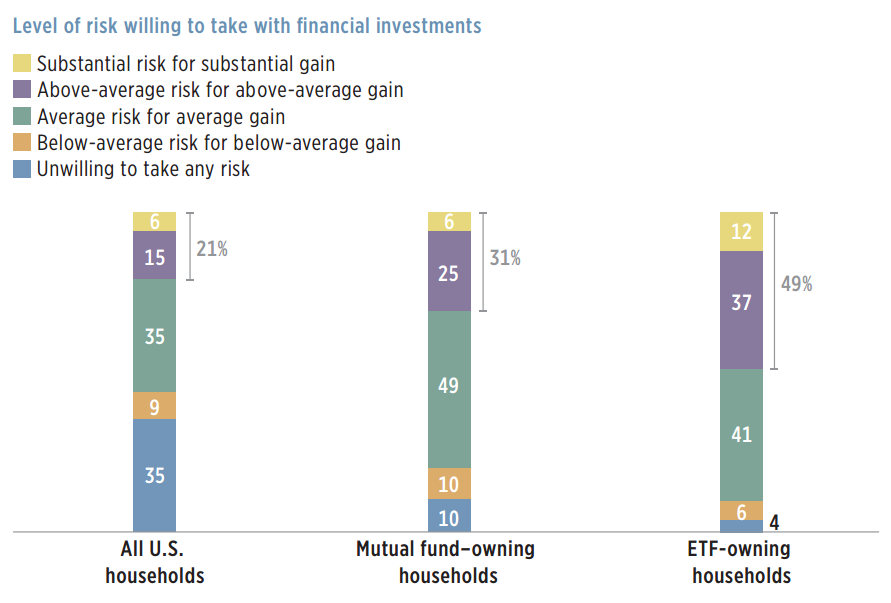

The same is true of the ETF world. In their infancy, there were limited ETFs. They added value and some form of protection for investors looking to build diverse portfolios with a rock-bottom cost of ownership. Most importantly, there was a small basic list to choose from. Now, with 1,411, the investment spectrum is seemingly endless. For those who don’t know what they are doing this is a dangerous reality. ETFs have emboldened investors largely because they are perceived as safe and diversified vehicles with low cost structures. Yet, an interesting study revealed ETF users have an appetite for risk almost double the average investor. As we’ve argued before, the perception that ETFs are somehow safer vehicles than mutual funds, or other investment structures, is likely adding to their misuse and, even, abuse.

FIGURE 2: ETF-OWNING HOUSEHOLDS ARE WILLING TO TAKE MORE INVESTMENT RISK Souce: 2015 Investment Company Fact Book

Souce: 2015 Investment Company Fact Book

So far I’ve made the case that the Internet has made it easier for investors to participate. Secondly, I’ve said the evolution of the ETF marketplace has created a false sense of security for investors. Both of these ultimately add to market volatility. The first does so by giving millions of unsophisticated people the ability to move quickly into and out of the market or its sub-segments. When times are good, retail investors pump money into whatever area of the market Jim Cramer endorses, only to yank it out the next time the financial markets head south, something people have forgotten they can do. ETFs will exacerbate the issue because they allow people to invest in areas where they may not have adequate expertise and where there is a perception of instantaneous liquidity—no matter how illiquid the underlying securities.

Looking back historically at volatility, it does appear a new trend is under way. The Internet, as we know it, has been around since basically the mid-1990s. ETFs have been in existence since the early 1990s but only “went viral” about 15 years ago. So, it begs the question, since these two forces have been at work together, have market declines become more vicious? You be the judge. Since 1950, there have been nine official bear markets. The first seven market declines fell on average 31% and lasted 7 months. The 8th and 9th decline occurred in 2000-01 and 2008-09, with an average decline of 54% and duration of 21 months. This is almost a 100% increase in terms of magnitude and a 300% increase in length.

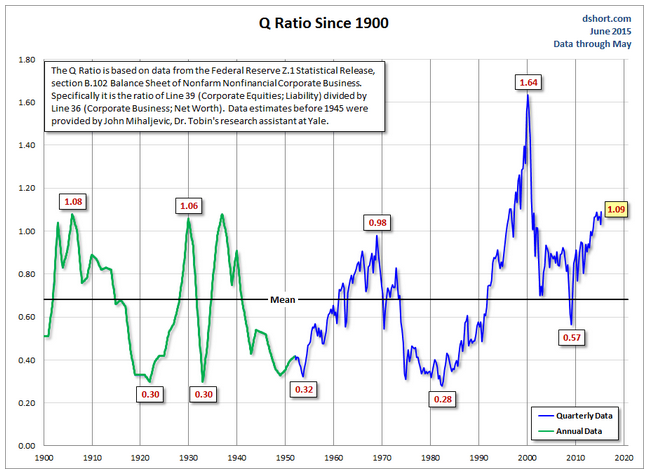

What if we were to see a third 50% plunge? Now, I’m not saying that will happen but, when you look at the next chart, courtesy of John Hussman, you realize that it’s certainly possible. It also makes it clear that expecting a mild correction from these valuation levels is a classic case of the triumph of hope over experience.

FIGURE 3: Q RATIO SINCE 1900 Source: Hussman Funds

Source: Hussman Funds

The constant question we hear is “When?” This is despite Warren Buffett’s advice to focus on the “what” not the “when.” We have tried to repeatedly, and frustratingly, reply we don’t know the when. As you can see in the Hussman chart, stocks became far more overvalued relative to replacement cost (which is what the Tobin’s Q Ratio measures) in early 2000.

However, there is evidence that what is already the third longest bull market may be running out of gas. The advance/decline ratio has deteriorated noticeably and the broad NYSE composite has flat-lined for the past year.

In addition, we are starting to see some hyper-extreme volatility in normally tranquil areas like government bonds. In fact, treasury bond fluctuations last fall were so violent that they should have only occurred once every few billion years, statistically speaking, according to Jamie Dimon, CEO of J.P. Morgan. Recent European bond market gyrations have also been literally off the charts in terms of improbability. If those types of shocking price swings can hit the highly liquid sovereign debt markets, imagine what’s going to eventually happen to a sector like Biotech when it starts to crack.

Biotech ETFs have been incredibly popular—and lucrative—as the Wall Street Journal just pointed out this week. Valuations are astronomical. Numerous members of this index are losing money and those that are profitable often sport triple digit P/Es. If you think investors learned their lesson from the tech bubble’s total implosion from 2000 through 2002—when the NASDAQ vaporized almost 90%--it appears as though another tutorial is needed. Maybe school’s not out for summer, after all.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

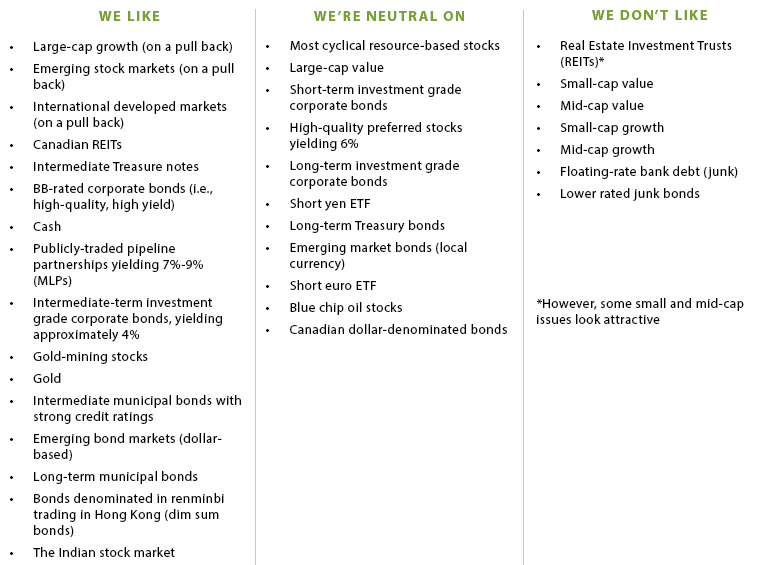

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

There were no changes this week.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

DISCLOSURE: This report is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any securities mentioned herein. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. All of the recommendations and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions as of the date of this presentation and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Information contained in this report has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, Evergreen Capital Management LLC makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness, except with respect to the Disclosure Section of the report. Any opinions expressed herein reflect our judgment as of the date of the materials and are subject to change without notice. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments or strategies to particular clients. Investors must make their own investment decisions based on their financial situations and investment objectives.