“The Fed’s dual mandate is that of arsonist and fire brigade.”

-JIM GRANT

“In their efforts to promote jobs and growth, central banks are trading the possibility of immediate economic gains for a growing risk of financial instability later.”

-MOHAMED EL-ERIAN, former Pimco CEO

“I do not think it works. I also think it is enormously dangerous.”

-WILLIAM WHITE (former Chief Economist for the Bank of International Settlements, and one of the world’s few senior bank officials to anticipate the global financial crisis), referring to ultra-easy monetary policies.

By David Hay / CIO, Evergreen Gavekal

(Reader’s Note: Introductions to Guest EVAs are meant to serve as summaries for those who don’t have time to read the full issue.)

The Great Inflation Debate, Take Two. In our February 17th Chartbook EVA, we entered into the always hotly contentious realm of attempting to determine the true level of inflation and, closely related to that, its trend. It goes without saying—but I will anyway—that there are few areas where the words “Believe those who are seeking the truth; doubt those who say they have found it” are more applicable.

In this week’s Guest EVA, we examine two essays on this controversial subject. The first is from one of my closest friends in the investment business, Grant Williams. The other is from a new friend, Anantha Nageswaran. As you will soon read, they take very different views of the CPI (Consumer Price Index) in the US, past and present.

In the first section, based on a significantly condensed version of Grant’s increasingly popular newsletter—Things That Make You Go Hmmm—a strong case is made that the real inflation rate is much higher than what is officially reported. This viewpoint has many prestigious adherents, including Michael Lewitt, author of The Credit Strategist. (Last year, I had the honor of sharing the stage with Michael at John Maudlin’s Strategic Investment Conference; accordingly, I can personally vouch for his impressive intellect.)

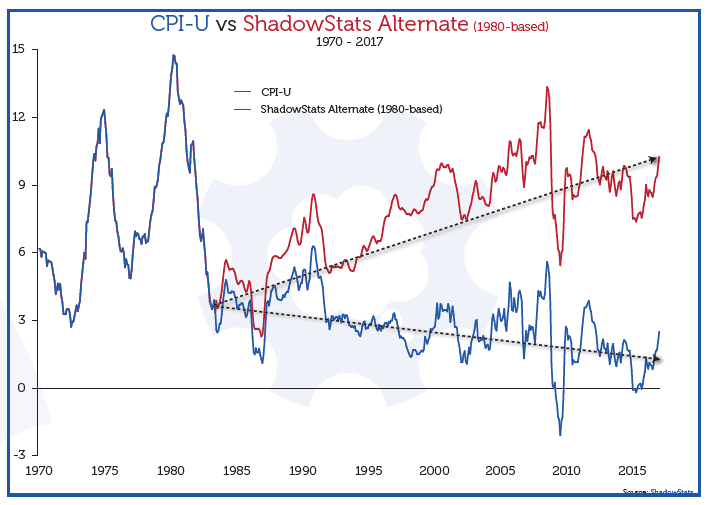

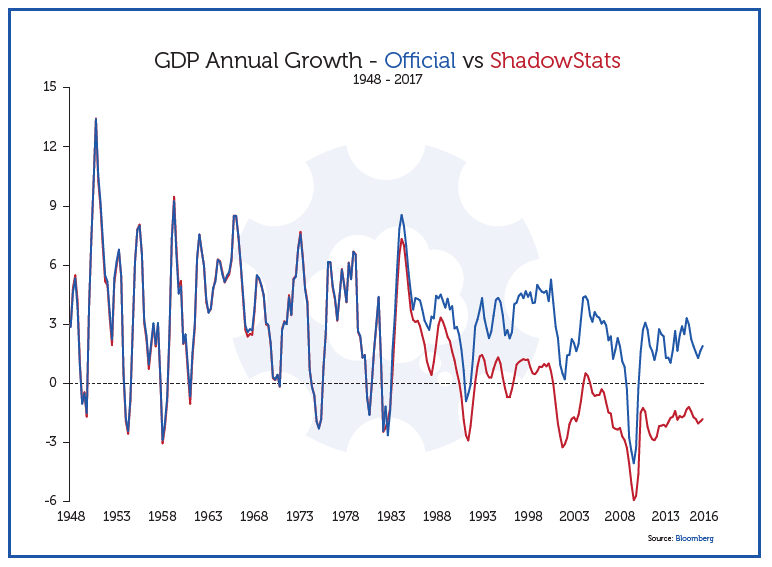

In Grant’s March 19th newsletter, he relies heavily on the work of John Williams (no relation) and the latter’s firm, ShadowStats. In a nutshell, Mr. Williams—as in, John—believes inflation is at least 2% per year understated. In fact, if you look closely at Figure 8 in Grant's section, it appears the actual difference is closer to 5%, possibly even 8%, per year. (To access the full version of Grant’s missive, click here.)

Interestingly, Grant and I debated this theory a couple of years ago and I made the point that if such adverse inflation “corrections” are valid, then the US has been in a deep recession going all the way back to the start of this century/millennium. If you look at Figure 11, you will see exactly this effect.

Because real economic growth is calculated by subtracting inflation from nominal GDP, the higher the inflation rate, the slower the growth rate. If you have, say, 3% nominal GDP growth, as we have today, and you subtract a 5% inflation rate, you are left with an economy contracting at 2% in real terms.

It’s unlikely anyone would consider me a Pollyanna-type, or a present-day version of Voltaire’s absurdly optimistic Dr. Pangloss, but I can’t believe the US has been in an almost continual and severe recession since 1999, as Figure 11 indicates. That just doesn’t pass the common-sense test (though Voltaire also once said “common sense is not so common”).

Further, as most of us know, consumer activity represents about 70% of total US GDP. Currently, there is some pronounced deflation going on in the retail sector, as Jim Grant recently discussed in his coveted newsletter, Grant’s Interest Rate Observer. This includes even the usually sedate grocery sector where a fierce price war is underway.

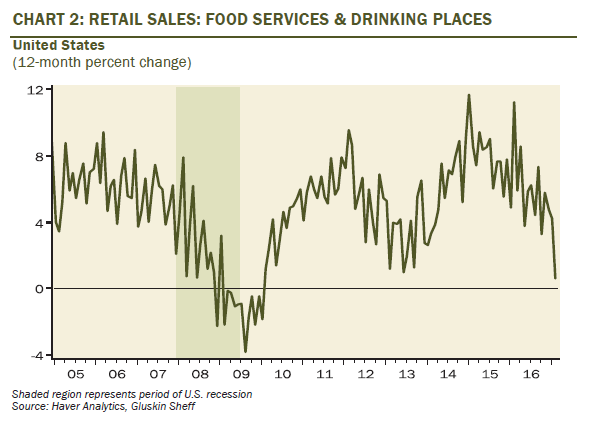

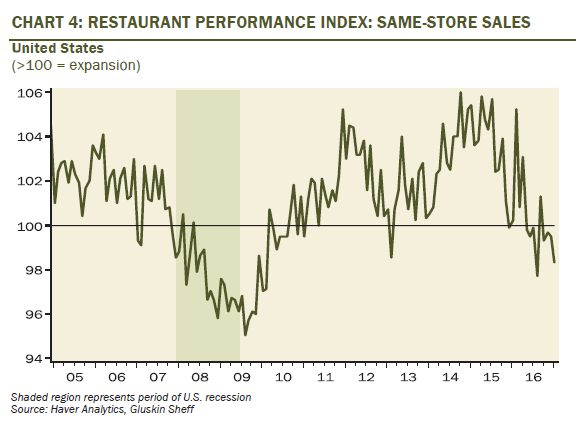

But I certainly agree with one of the other Mr. Williams (Grant) when he asserts that the US economy isn’t exactly en fuego. The recent distressing news out of the critically important auto sector is indicative that the US economy is very late in this up-cycle (price-cutting is also rampant with motor vehicles, another reason to question the high inflation argument). Similarly, as my numero uno, go-to economist, David Rosenberg, recently observed, restaurant sales are an excellent leading indicator for overall consumer spending and the current trend is definitely not appetizing.

FIGURE 1

FIGURE 2

Source: Haver Analytics, Gluskin Sheff

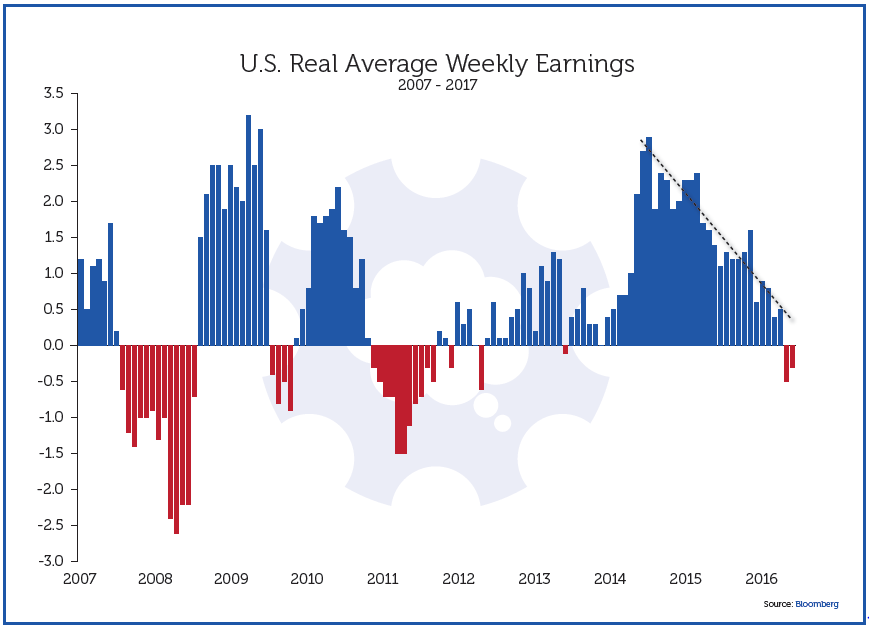

Moreover, as Grant highlights, real household earnings are also heading south. It’s hard for consumers to feel good about busting out the credit cards when their after-inflation income growth is trending toward zero, or even below.

FIGURE 3

Source: Things That Make You Go Hmmm

Source: Things That Make You Go Hmmm

Returning to the inflation debate, one argument in this regard I am sympathetic to is when it comes to asset prices, a view shared by our next Guest EVA author, Anantha Nageswaran. Anantha has a resume that should intimidate almost everyone in the investment business, including your appropriately humbled EVA scrivener. His most recent gig was as Chief Investment Officer of the elite Swiss private bank, Julius Baer. Additionally, his academic credentials are as lengthy as a congressional filibuster. Accordingly, I am gratified Anantha is an EVA reader and that he took the time to eloquently respond to my March 17th epistle on the Fed’s new-found embrace of the long-deceased Swedish economist Knut Wicksell’s theories on the natural interest rate.

His email comments were so impressive that I immediately asked him if he would write a short Guest EVA to accompany Grant’s abridged essay. Fortunately, he was kind enough to agree.

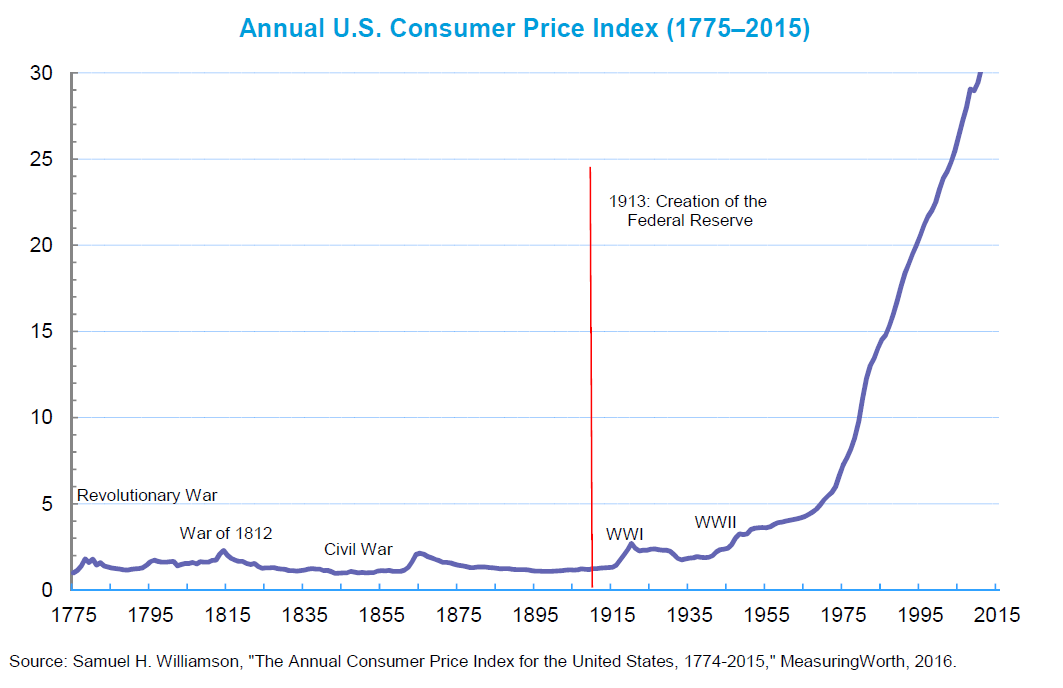

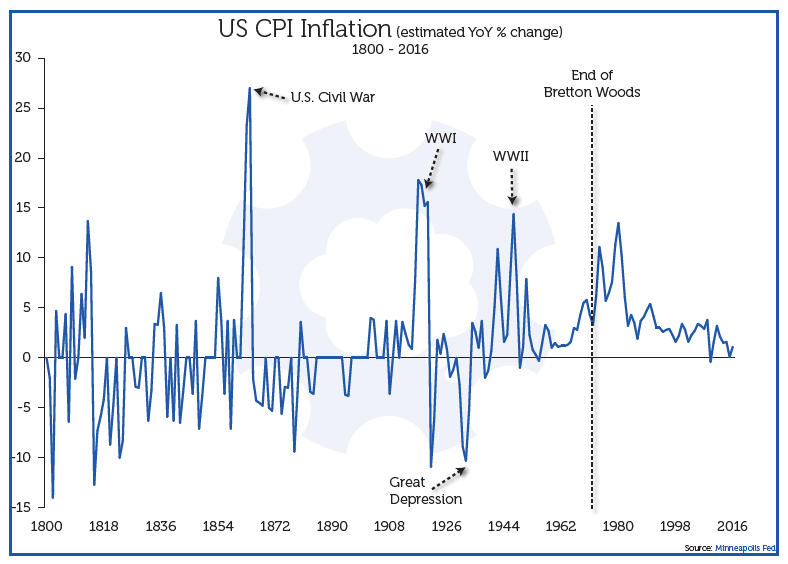

Like me, Anantha has serious reservations about the notion that US inflation has been running far hotter than has been officially reported. However, as you will read, he does point out, as have others, that deflation was much more common in America prior to the Fed’s creation in 1913. To prove his point, the following chart makes it clear that the Fed hasn’t been a reliable protector of the US dollar’s purchasing power since its formation over a century ago, even using the official CPI calculation. (In fairness, Anantha perceives a more robust US economy than do Grant or I.)

FIGURE 4

Source: Goode Hable Pak at Morgan Stanley

Source: Goode Hable Pak at Morgan Stanley

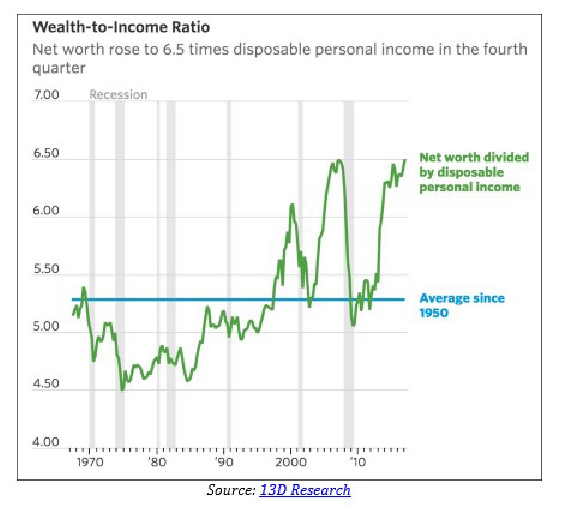

Yet, as mentioned above, he does feel that high inflation has been created by the Fed—and its similarly incontinent central bank peers around the world—but that it has been in asset, not consumer, prices. He believes, as do I (and I know both Grant Williams and Michael Lewitt would concur), that nearly a decade of recklessly easy monetary policies has inflated stocks, bonds, real estate, collectibles, et al, to bubble levels. If you doubt that, despite being an EVA reader, please reflect on the charts below.

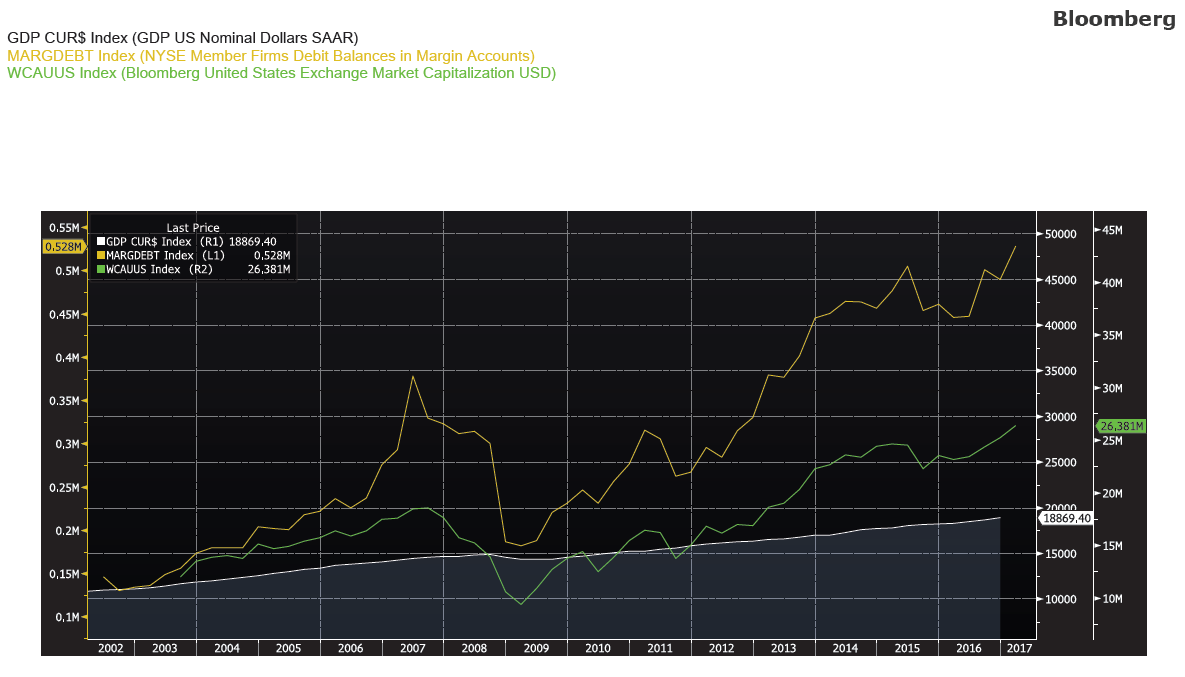

FIGURE 5 - INCREASES IN MARGIN DEBT, THE STOCK MARKET, AND GDP SINCE 2002

FIGURE 6 - TRIPLE TOP IN HOUSEHOLD NET WORTH RELATIVE TO INCOME?

Source: Bloomberg, 13D Research

What is particularly ironic about this is, as Anantha observes, central bankers have gladly taken the credit for bringing down consumer inflation while washing their hands of the asset inflation their policies have created. Call me hopelessly retro, but I’ve never thought hubris and hypocrisy were the hallmarks of the world’s preeminent central bank.

FAKE VIEWS (PART II)

By Grant Williams

(Reader’s Note: Grant’s article was too long to present in full-form. As such, we have compiled excerpts from Fake Views (Part II) below. Breaks in writing are noted with ellipses throughout this section.)

The twin constructs of fake views which began in Part I of this letter, and this week’s continuation around things not being how they seem, are important to understand so let’s begin Part II with an extract from a speech delivered by Janet Yellen at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research in late-January:

(Janet Yellen): “...inflation is likely to move up to 2% over the next couple of years, aided by a strong labor market. In light of the progress that has been achieved towards our employment and inflation objectives and the committee’s assessment of the outlook, the FOMC raised the target rate for the federal funds rate at its December meeting by twenty-five basis points to between fifty and seventy-five basis points. The committee judges however that the stance of monetary policy remains moderately accommodative and so policy should support some further strengthening in labor market conditions and the return of inflation towards our 2% goal.

With the unemployment rate near its longer-term normal level and likely to move a bit lower this year, the natural question is whether monetary policy has fallen behind the curve.

The short answer, I believe, is no.”

And so, in the wake of her illustrious immediate predecessors, Drs. Greenspan and Bernanke, Janet Yellen once again confirms that, no matter what the evidence to the contrary may be, the delusion which unfortunately must sit at the heart of the world’s most important central bank is firmly entrenched.

The simple truth is that the Fed has never been so far behind the curve.

…..

Inflation is, of course, ground zero for disingenuity and downright fake views on the part of central banks and governments from Washington to Warsaw and from London to Lisbon and nobody does a better job of tracking and explaining the vagaries of official inflation calculations than John Williams of ShadowStats and I will be leaning heavily on John to help me out here.

(Incidentally, John’s ShadowStats service is an incredibly useful one and you can find out more about it by clicking HERE)

Quite apart from the pressure rising prices places on the average household, so many transfer payments are linked to inflation that it is, of course, in every government’s best interests to measure inflation at its lowest possible level. Here’s the official description of CPI from the BLS website:

The Consumer Price Indexes (CPI) program produces monthly data on changes in the prices paid by urban consumers for a representative basket of goods and services.

That representative basket of goods and services used to be fixed to ensure a consistent evaluation of how easy (or otherwise) it was for the average consumer to maintain a fixed standard of living. Each month it contained the same components at the same fixed weighting so it was easy to calculate the increased income a consumer might have to earn over a given period in order to maintain their standard of living and that same method for calculation was used (according to the BLS themselves) all the way back to the 1700s and, indeed, prior to the end of WWII, the Consumer Price Index was actually called the Cost of Living Index.

Here’s how the annual rate of change in inflation looks going back to 1800 (as estimated by the Minneapolis Fed using a variety of sources).

FIGURE 7

Source: Things That Make You Go Hmmm

As you can see, the annual rate of inflation saw big spikes during the U.S. Civil War and the two World Wars and a big dip immediately after WWI and again during the Great Depression.

You can also see here that, for fully 100 years, during the biggest economic, demographic and technological expansion in the nation’s history, deflation was the norm with the citizens of the U.S. spending more time watching their cost of living fall than they did worrying about rising prices as technology rapidly brought down the cost of goods.

WWII saw another understandable spike in inflation which was wrestled to the ground before, again understandably, sharply rising prices returned in the 1970s.

The response to that inflation scare by the Fed Chair at the time, Paul Volcker, was, of course, to jam rates up to 20%. Anybody who has either given but a cursory glance to financial history or spent thirty seconds looking at a long-term chart of the fed funds rate, treasury yields or the gold price is familiar with the policy response, but there was another, far quieter response to the runaway inflation of the 1970s and it came, as these things often do, from the academic community.

…..

ShadowStats publishes its own inflation numbers which maintain a constant measurement of the CPI inflation data based on the 1980 methodology and here is what the two different forms of measurement look like when placed alongside each other:

FIGURE 8

Source: Things That Make You Go Hmmm

It will come as no surprise to anybody that the new version of the calculation produces consistently lower results while the original method heads relentlessly in the opposite direction. John Williams calculates that the changes currently understate CPI inflation by 5.1%.

…..

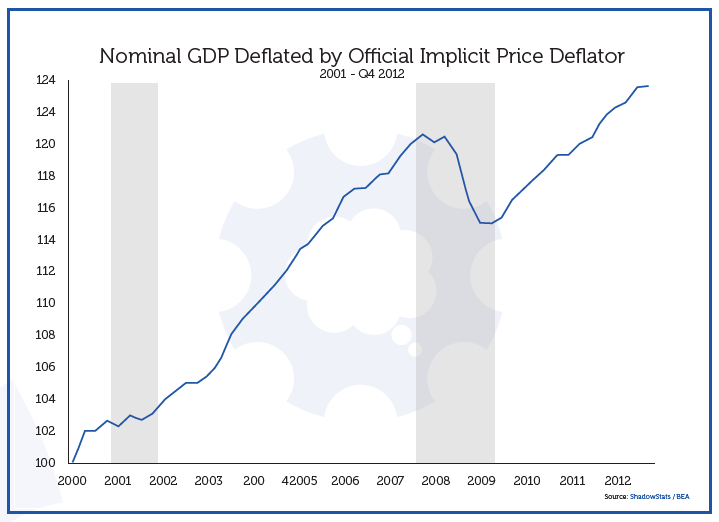

The idea that… things are not as they seem, is not just readily apparent in the inflation numbers, but it fits perfectly with the fake views narrative and bleeds into everything — even the GDP data. Here’s a chart showing headline real GDP in the U.S. going back to 2000.

FIGURE 9

Source: Things That Make You Go Hmmm

The chart shows nominal GDP deflated by the official GDP price deflator and is seasonally adjusted.

As you can see, the U.S. economy climbed back above its pre-2008 level in 2011 on an official, inflation-adjusted basis. Happy days!

However, there are a couple of glaring anomalies in that chart. Here’s John Williams again:

(ShadowStats): No other major economic series has shown a parallel pattern of full economic recovery and beyond. Either the GDP reporting is wrong, or all other major economic series are wrong. While the GDP is heavily modeled, imputed, theorized and gimmicked, it also encompasses reporting from those various major economic series and private surveys, which attempt to mirror real-world activity. In a related area, the 2001 recession has disappeared from GDP reporting, contrary to other major economic series. Flaws in the GDP inflation methodologies have created the “recovery” and erased the previous recession.

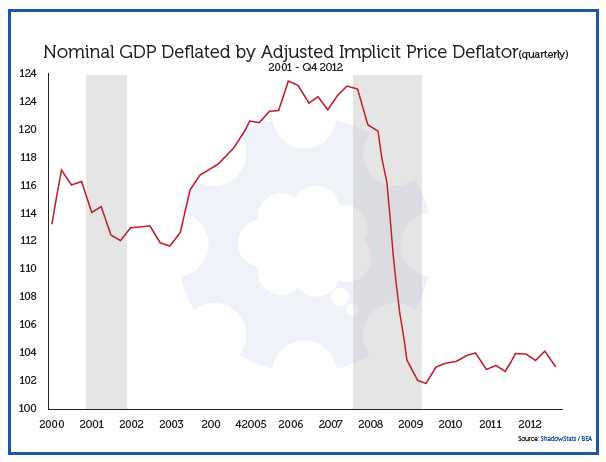

The graph below plots the GDP corrected for the inflation understatement inherent the GDP deflator of roughly two-percentage points of annual inflation. That inflation understatement resulted from hedonic-quality adjustments, again, as discussed in Hyperinflation 2012.

FIGURE 10

Source: Things That Make You Go Hmmm

Note that the 2001 recession is back, and that the “2007” recession really started in 2006, consistent with the downturn in the housing market. The economy plunged through 2008 into 2009. Instead of rebounding to full recovery, as seen in the headline GDP, however, the corrected real GDP has been bottom-bouncing, stagnant at a low level of activity. It now is turning down again. The corrected version appears to be much closer to the reality of common experience.

And, as you can see over time, the manipulation of inflation numbers has a profound optical effect on the strength of the U.S. economy.

FIGURE 11

Source: Things That Make You Go Hmmm

Why does this matter? Well, given recent developments, the fake views of the latest incumbent of the chair of the Federal Open Markets Committee in terms of the strength (or otherwise) of the U.S. economy are highly likely to become problematic.

In raising rates another 25 basis points on March 15th, Janet Yellen took the step for which she had been preparing the markets for some considerable time. Going into the press conference she and the rest of her colleagues on the FOMC must have been delighted to see expectations for a 25bp hike as close to 100% as they are ever going to get. Translation? We can raise without the market starting to wobble.

Unfortunately, the very day Janet finally took the upper bound of the federal funds rate back up to 1%, the Atlanta Fed GDPNow tracker pulled the rug out from under her feet, falling to sub-1% after having reached 3.4% just a few weeks ago.

Hardly helping matters is real average weekly earnings growth which has been negative for the last two months, continuing a downtrend which has been in place since the data peaked way back in February 2015.

…….

The Fed have missed growth estimates every year since 2010 — and by an almost unfathomably wide margin each time. Similarly, their forecasts for the fed funds rate have been so far off beam as to raise doubts as to why any serious investor would take what they say at face value.

That lack of any real credibility hasn’t hurt them thus far because it has resulted in ascending asset prices so investors can sit back, listen to the fake views, chuckle and carry on buying the dips safe in the knowledge that the Fed doesn’t have the balls to raise rates meaningfully and, should anything untoward happen like... oh, I don’t know... maybe a 1% correction — the Fed will step in with more accommodation.

You see, that’s the trouble with fake views; you start off uttering them to drive a chosen narrative but you end up being forced to maintain and defend them with both your reputation and your credibility on the line should you fail. Mere mortals such as you and I don’t have the luxury of being able to defend any fake views of our own with the full faith and credit of the United States government or, God forbid, the blank check that an electronic printing press offers, but these people do and they are shameless.

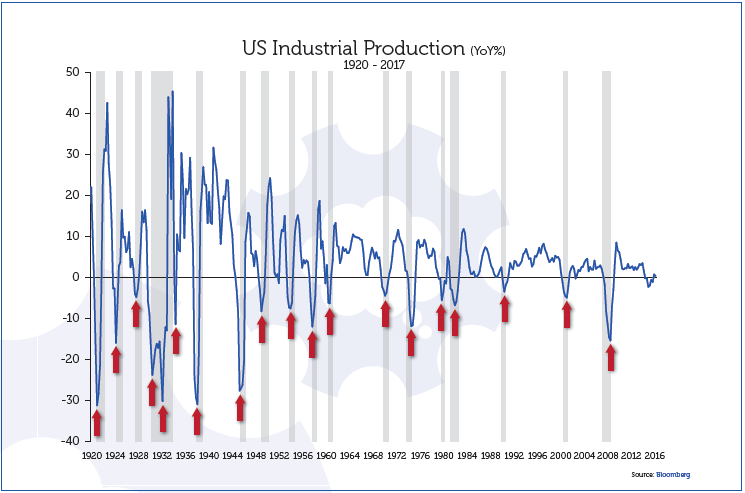

Ultimately, however…things will be shown to be decidedly not what they seem. On March 17th, alongside the claims of an economy which is robust enough to stand another round of tightening, the latest U.S. Industrial Production print was announced and, as we have shown in this publication previously, this is just about as concrete a barometer for an upcoming recession as any investor could wish for.

FIGURE 12

Source: Things That Make You Go Hmmm

Assuming… things are not what they seem, we can join several dots as it would naturally follow that assets are understandably being priced to a narrative which has been deliberately built around a series of fake views. Namely; the economy is doing well, equities are not over-valued, the Fed is not behind the curve, the dollar is going to the moon, volatility is dead, deflation is dead but inflation is under control, the debt ceiling will be raised without issue and President Trump will get his tax cuts and his infrastructure spend passed by Congress but not suffer any problems with higher interest rates putting the squeeze on the now-$20 trillion dollars the United States owes the rest of the world.

So, all this being said, we need to ask ourselves one crucial question; if such views are fake and things are not as they seem then what should we, as investors, do about it?

This is the perfect set-up for the contrarian investor — overvaluations as far as the eye can see, a clearly false (or, in this case, fake) narrative and universal buy-in to same on the part of market participants.

PRESIDENT TRUMP NEEDS TO DRAIN THE MONETARY POLICY SWAMP

By Anantha Nageswaran

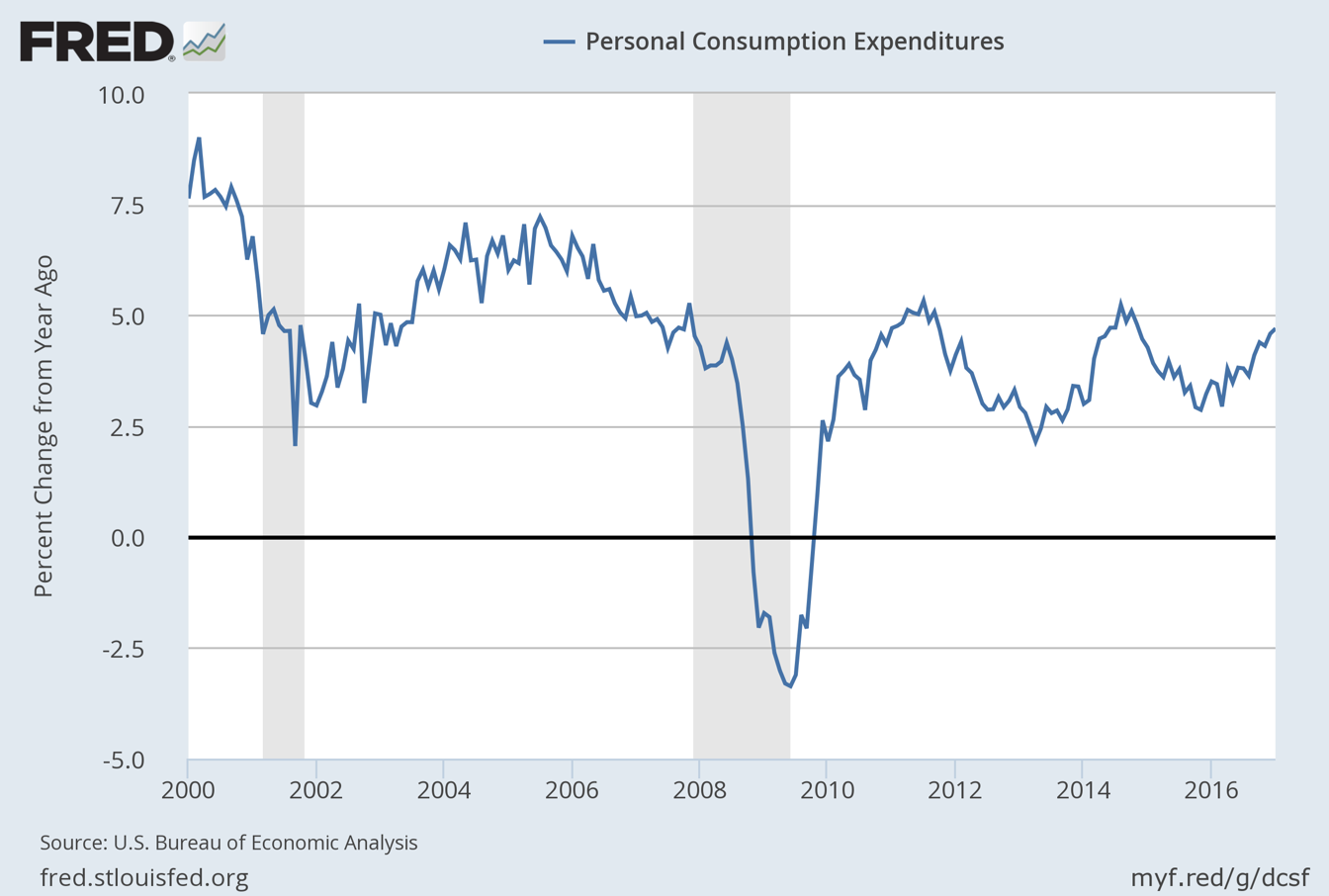

Just before the first quarter ended, the United States released the March data for its most comprehensive (excluding the GDP deflator, of course) inflation indicator—the Personal Consumption Expenditure: Chain Price Index. The annual percentage change (PCE inflation rate) in the headline index had crossed 2.0%. It read 2.1% when rounded off. Between January and September 2015, it hovered at around 0.2%. The last time it was above 2.0% was in April 2012. The core index reflected an annual percentage change of 1.8%. Is inflation about to raise its head in the United States in a big way?

It is well known that the Federal Funds rate hovered at around 0.0% to 0.25% since December 2008 until the Federal Reserve made a first rate hike after seven years in December 2015. The next one followed a year later in December 2016 and the third rate hike in March. The Federal Funds rate is still below 1.0%. Is the Federal Reserve behind the curve?

The two questions posed above are possible to answer independently, even though many think that they are interconnected. In other words, some think that because the Federal Reserve has done too little too late, a nasty resurgence of inflation in the United States is inevitable. But that is not altogether true. One can agree on the Federal Reserve without agreeing with the prediction on inflation, which is the stance I take in this brief note.

The reason why the Federal Reserve ends up creating bubbles and busts is that it is too slow to begin tightening. When it does, it overreacts because it is already late in doing so for the cycle and the strains and faultlines of the preceding boom had begun to manifest in any case, especially in asset markets and in risk-taking. That was the case in 1987, in 1999-2000 and in 2004-07. The only exception was in 1994 when it moved to raise rates aggressively before asset prices had entered bubble territory. That is why the United States economy narrowly avoided a recession and there was no bubble to prick, then. But, that was the exception and not the rule. Those were the days when Dr. Greenspan actually worried about irrational exuberance in the stock markets.

But, this time around, the Federal Reserve has stuck to the script of the last three decades. It has begun normalising (note, it is not the same as ‘tightening’) monetary policy very slowly. Indeed, it has moved from being ‘recklessly ultra-loose’ to being ‘somewhat recklessly loose’ in the last two years. Doug Noland put it very well in his weekly credit bulletin on March 4:

“The current remarkable cycle has brought new meaning to the phrase ‘Behind the Curve.’ Rates were cut from 5.25% starting back in September 2007. By December 2008, they had been slashed to zero (to 25bps), with the DJIA ending the year at 8,876. Now, with the DJIA at 21,000, Fed funds sit at only 0.75%. Rates have budged little off zero despite record securities prices, record corporate bond issuance, record home prices and a 4.8% unemployment rate.

While Q4 data will be out soon, it appears that 2016 posted the largest Credit growth since 2007. Through the first three quarters of 2016, non-financial Credit expanded at an annualized pace of just under $2.4trn, not far off 2007’s record $2.503trn.

For comparison, non-financial debt expanded $1.259trn in ‘09, $1.589trn in ‘10, $1.309trn in ‘11, $1.916trn in ‘12, $1.545trn in ‘13, $1.807trn in ’14 and $1.931trn in ‘15.

U.S. Credit growth and economic activity had attained sufficient self-sustaining momentum by 2014 and 2015 for the Fed to have launched so-called ‘normalization.’ It was a major policy blunder not to have this process well underway by 2016. The Fed basically disregarded domestic considerations as it postponed rate adjustments after its single December 2015 baby-step.”

That said, the Federal Reserve is right to make an attempt to catch up with the economic cycle now. It is better late than never. The consequences of remaining recklessly ultra-loose would be worse. Yes, the cycle is about eight years old, but, look at the cyclical indicators:

a. Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) growth is accelerating

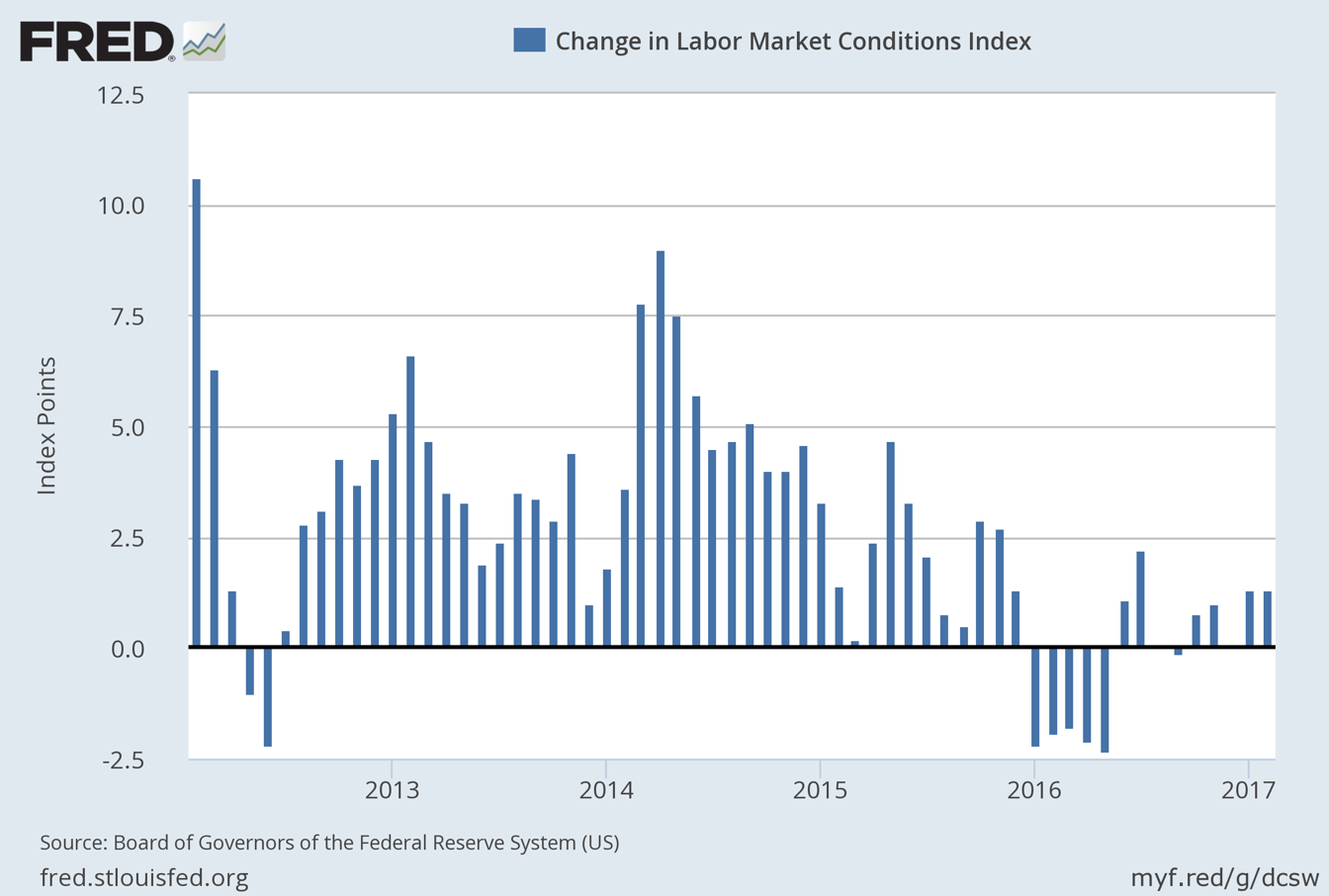

b. Change in the Labour Conditions Index is now positive. It showed weakness in the early part of 2016. That phase has passed.

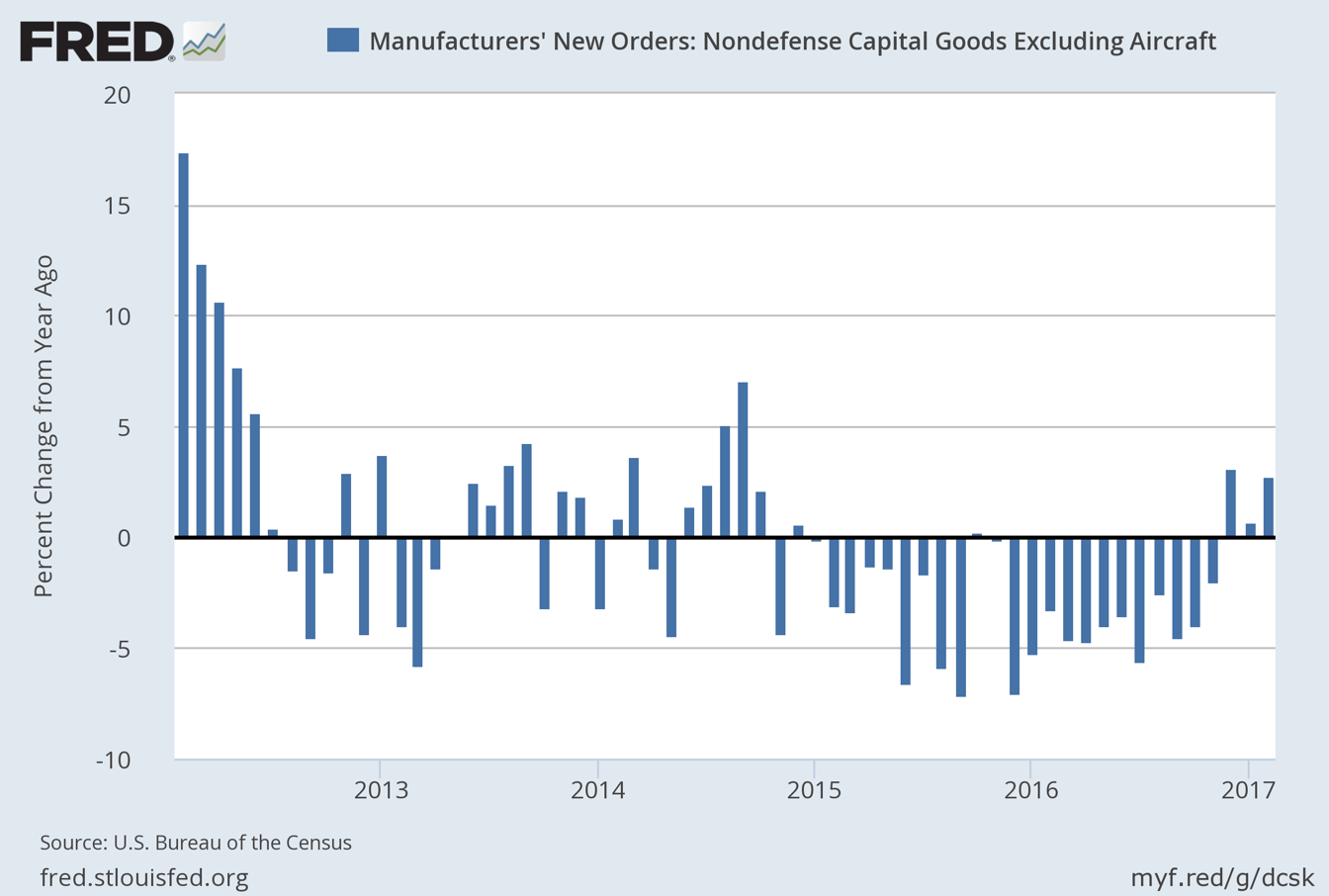

c. The Manufacturers’ New Orders (Non-Defence capital goods excl. aircraft) is now showing positive change in the last three months (y/y) after a long spell in the negative territory.

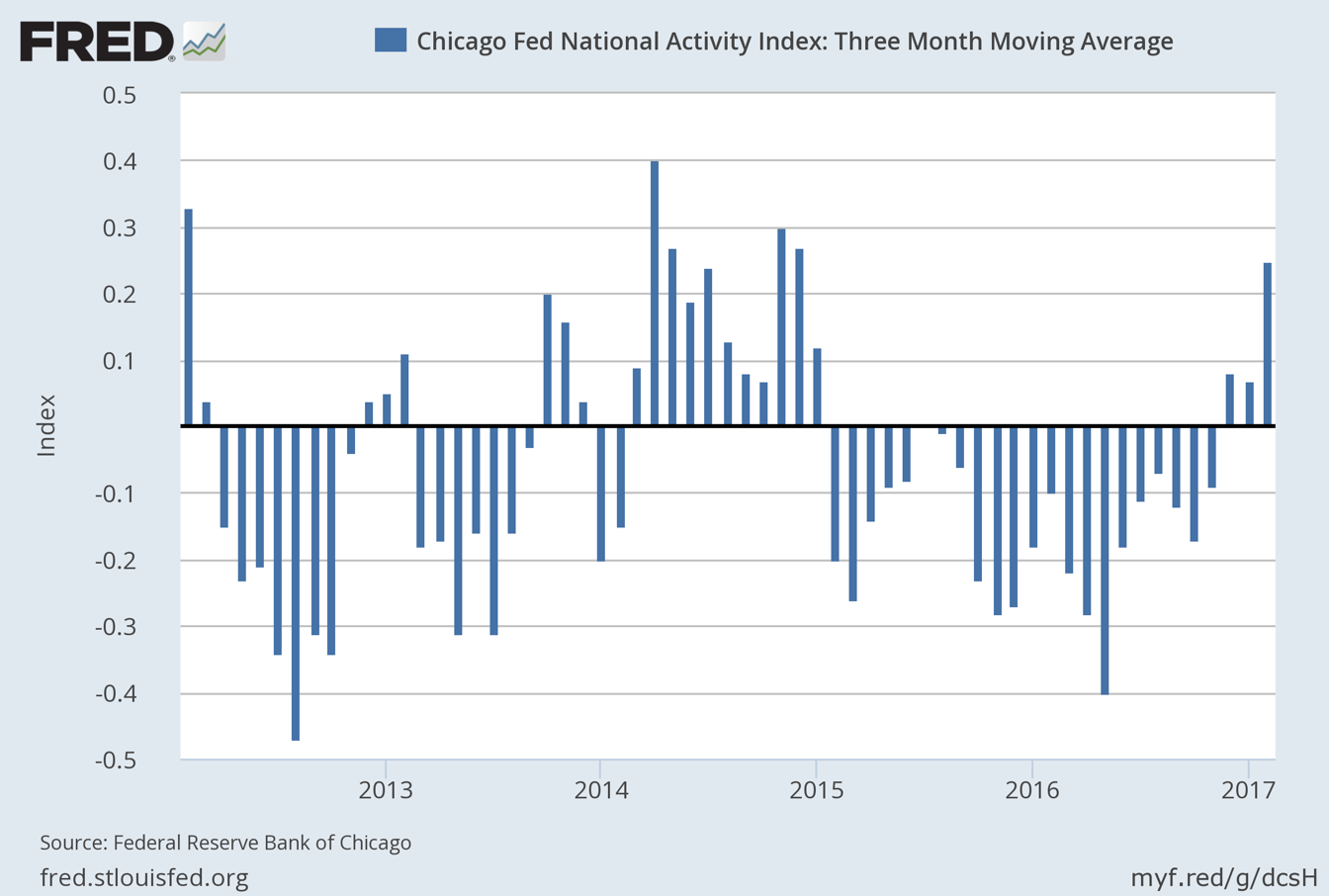

d. Chicago Fed National Activity Index is accelerating now

FIGURE 13

FIGURE 14

FIGURE 15

FIGURE 16

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

What these indicators show is that, from a real economy standpoint, there is momentum.

Whether it is because of the hope for a major change in the regulatory regime, or the delayed stimulative effects of all the liquidity in the system, or the strain in the oil industry having at least temporarily receded, it is hard to say. However, one should not discount the possibility that the belated normalisation of monetary policy by the Federal Reserve and the prospect of the stultifying regulations imposed by the Obama administration being lifted are improving the mood among households and business enterprises in the country. Persistently low interest rates reinforce deflationary mindsets and thwart capital formation by businesses. It is well documented now. If only the nanoscope and the laser-like focus that commentators had brought to bear on the new administration in the United States had been deployed with the previous regime too, things might have turned out differently, and for the better, for the U.S. and world economies.

So, the Federal Reserve is right to make hawkish noises now. Further, there is clear talk of fiscal policy becoming looser. It has not done so yet. But, the signal is for a regime shift in fiscal policy and that does call for a less accommodative monetary policy.

Where the Federal Reserve has always erred—including in this cycle—is to allow asset prices to get well ahead of fundamentals as it has done in the last several years. So, by the time fundamentals actually begin to turn, asset prices are way out of alignment already. There is no more good news to be priced in. Even if the tightening is gradual, it is enough to stop the economy in its tracks or tip it into a recession because too much risk has accumulated in financial markets by then.

One risk that the steady diet of low and lower rates could have spawned needs to be acknowledged here. That is the emaciation of the strength of the economy to withstand even remotely normal interest rates because the Federal Reserve had gotten ‘economic agents’ hooked on a diet of exceptionally low interest rates for too long a period. The addiction began three decades ago and it has reached its peak in the most recent cycle. The damage it has caused was partially revealed in the 2008 crisis. But, the cure for de-addiction, post-2008, has been more of the same drug except that the dosage has been raised! If there is one more recession (and there always is), it is hard to predict what would follow in its wake. It could also deal a serious setback to America’s geopolitical dominance.

Therefore, the Federal Reserve is one institution that is in genuine need of overhaul. The swamp—the monetary policy framework—has to be drained, for sure.

As for inflation rearing its ugly head because the Federal Reserve has been too slow in removing policy accommodation, that gives too much credit to central banks for having tamed it in the first place. That myth has not been adequately busted although some rare central bankers have confessed to their bystander status in the arena of inflation.

Inflation did go into a secular decline from the 1980s onwards. Many reasons—globalisation, the emergence of China as a low-cost exporter, a swoon in the price of oil that lasted two decades—were behind the easing of upward CPI pressures. Above all, the loss of bargaining power of labour unions and the erosion of their membership base were big factors. Despite the steady decline in labour force growth which should have pushed up wages, what happened was that globalisation expanded the pool of labour, allowing for a massive labour cost arbitrage.

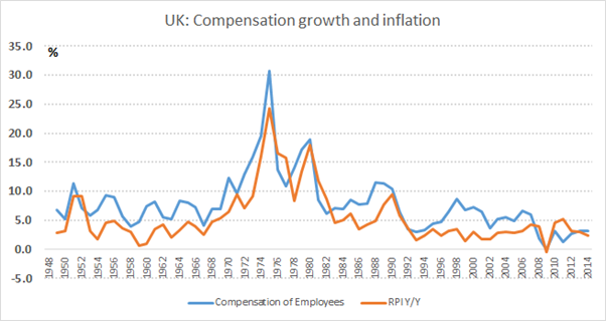

There are two charts that show the strong correlation between inflation rates and compensation growth in the US and in the UK.

FIGURE 17 - AMERICA: PCE INFLATION AND CHANGES IN THE AVERAGE HOURLY EARNINGS (Y/Y % CHANGE)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

FIGURE 18 - THE UNITED KINGDOM: RETAIL PRICE INDEX (Y/Y % CHANGE) AND EMPLOYEE COMPENSATION (Y/Y % CHANGE)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Accordingly, there is merit in the argument that there was only a marginal role for central banks, their monetary policy and inflation targeting in this outcome—the secular decline in the inflation rate—in the last three decades. They had not achieved ‘great moderation.’ The above factors did and, of course, the cons of the above manifested in boom-bust cycles, wealth and income inequality, social consequences (destruction of communities) and in the rise of polarising and intolerant nationalism.

Asymmetric monetary policy—quick to ease and slow to normalise—in the United States (in vogue in the last three decades) did cause inflation. But, it was not in the prices of goods and services. Given worker insecurity and labour arbitrage, it manifested itself in asset prices. Given the unofficial peg to the U.S. dollar around the world, when America eased monetary policy, the rest of the world did. Thus, these asset price manifestations were exported globally.

What is the outlook for traditional inflation then? To reiterate, emasculation of labour was the big factor in the taming of inflation. After the first twenty-five years of post-WWII boom times for labour—the heyday of America’s unionized workforce—the US had become a high-cost production venue and it began to bleed market share. It was inevitable that labour’s domination peaked in the Seventies. The pendulum swung towards higher returns on capital, versus labour, in the Eighties. The crisis of 2008 should have ended that phase. But, it may not. The wheels are not going to turn in favour of labour. Despite restrictions being placed and contemplated on the outsourcing of labour and offshoring of manufacturing and services, labour insecurity is unlikely to fade and its consequent restraint on wage growth will, therefore, remain. Rapid technological changes will ensure that. That is bad news for inequality and for social stability.

Unless the talk of helicopter money returns and is acted upon, old-fashioned inflation will not return. If anything, the risk of that happening is higher in continental Europe since the European Central Bank appears petrified of even talking about rolling back its quantitative easing programme. The risk appears lower in the U.S and in the UK. Europe, led by Germany, had been the bastion of price stability in the last several decades, whereas US and UK were more tolerant of inflation. How times change?!

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.