“Owners of stocks…too often let the capricious and irrational behavior of their fellow owners cause them to behave irrationally as well.”

-WARREN BUFFETT

POINTS TO PONDER

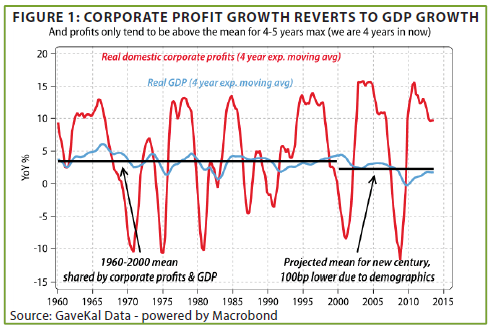

1. Various prior EVAs have noted that bull markets rarely last as long as five years (this one will hit that age on March 9th) but, if

they do, the eventual correction is severe. Similarly, GaveKal’s Will Denyer points out that profit margins mean revert (in this case,

head down) after four to five years. Corporate America is now in year four. (See Figure 1)

2. Encouragingly, and contrary to popular belief that only part-time hiring has been robust, star economist David Rosenberg has

observed that 1.5 million full-time jobs have been generated in the last year, while part-time employment fell by 188,000.

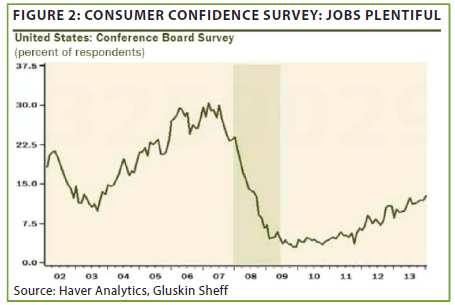

3. Consumer attitudes toward the employment situation are definitely improving. However, they remain at roughly the lows of

the early 2000’s recession. (See Figure 2)

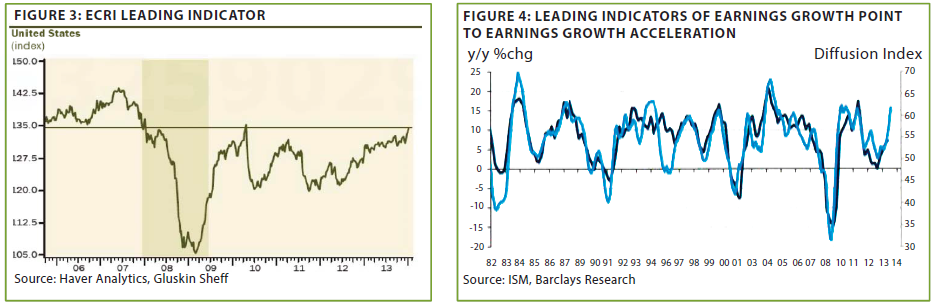

4. As mentioned several times in past EVAs, the economic forecasting firm ECRI has predicted the last three recessions, unlike

any of its competitors. However, it did incorrectly predict a US recession for 2012, and now its leading indicator index is in a

measured, but steady, uptrend. The important Institute for Supply Management (ISM) New Orders Survey is revealing even stronger growth. (See Figures 3 and 4)

5. Most US industries are operating below their full production potential. The oil and gas sector is a glaring exception to that

condition as it is running at 100% of capacity. This bodes well for suppliers to this sector.

6. Goldman Sachs recently disclosed that the US stock market is trading at 16 times 2014 earnings estimates. While that sounds

reasonable, the only times over the last 38 years that stocks have traded at a forward P/E of 17 or above was in the late ‘90s bubble and very briefly 10 years ago. Moreover, adjusting profits for present peak margins (unlike in 2004) makes this even more stretched.

7. James Mackintosh, of the Financial Times, recently wrote an article highlighting that 33 stocks in the S&P 500 are trading at

10 times both book value and sales. Putting this into perspective, there were only 25 stocks with those nosebleed valuations during the frothiest stage of the dotcom bubble. (However, in the 1000 largest companies, there are 84 stratospherically-priced issues today versus 200 in early 2000.)

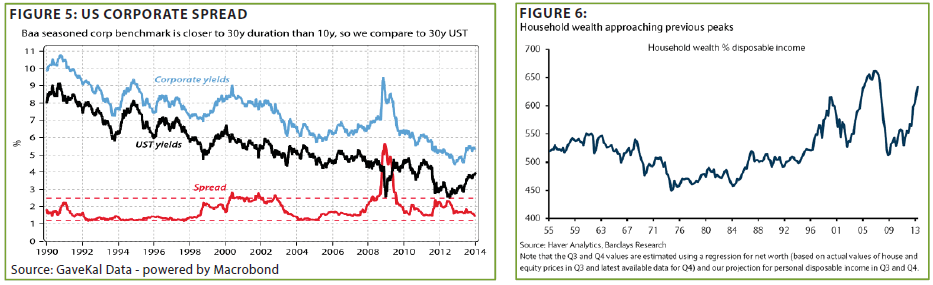

8. Evergreen has been a strong advocate of US corporate bonds for most of the last seven years, if not longer. Now, though,

spreads (the difference between their interest rates and those of Treasuries with similar maturities) have become uncomfortably

tight. (See Figure 5 below, left)

9. Household net worth is approaching the prior 2007 peak relative to disposable income. This has helped support consumer

spending, at least among the affluent. However, given the inherent cyclicality of asset prices, long-term investors should be

considering the implications of the inevitable downturn. (See Figure 6 above, right)

10. The market crash in October 1987 is now more than 26 years in the past. Consequently, it’s easy to forget that the US economy

was expanding at a boom pace of 6.8% when that occurred, mere months after a new Fed chairman, Alan Greenspan, took the helm.

11. The Canadian dollar has been exceedingly weak versus the US currency over the past year. This is despite the growing

likelihood that Canada will be the only advanced economy to soon be running a budget surplus, further burnishing its rare AAA

sovereign credit rating.

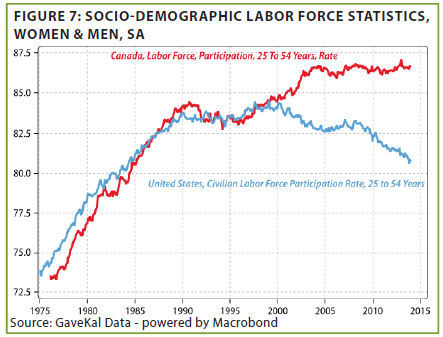

12. One reason often given for the loonie’s weakness relative to the dollar is the supposedly stronger nature of America’s

recovery. Yet, when considering the substantial divergence between the US and Canada over the last few years by the participation rate in the key working age cohort of 25 to 64, this explanation seems questionable. The separation since 2010 continues a trend that has been in place since 2000, perhaps an unintended consequence of the Fed’s chronically easy money stance since then which may be undermining our American economy’s innate vitality. (See Figure 7)

13. The IMF has recently issued two potentially significant warnings. One involves its growing anxiety over deflation, particularly

in Europe. The other pertains to debt levels that are becoming unmanageable. Their proposed solution on the latter issue is for a

stealthy and one-time (supposedly) wealth tax.

14. The news out of China continues to indicate a full-blown credit crunch is brewing. Based on the fact that it accounted for

one-half of global growth from 2007 to 2012, this is more than just a Chinese problem.

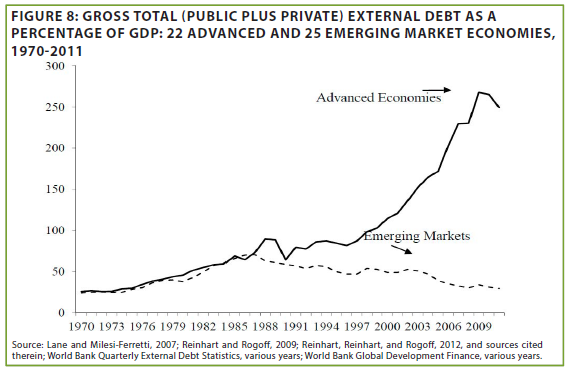

15. It’s ironic that concerns over external debt in emerging nations has been a key factor in their recent bond and stock market

turbulence considering how much less in-hock the developing world is versus the “advanced” economies. (See Figure 8)

Making lemons out of lemonade. We’ve all got our favorite anecdotes, and one of mine, unsurprisingly, pertains to investor

behavior, or, more accurately, misbehavior. This is a story I’ve relayed before, but it was a long time ago, and I believe it is worth

repeating. It involves the best performing mutual fund of the decade from 2000 to 2009.

For starters, it’s important to realize this was not a terrific market era. In fact, 2000 to 2009 was the lowest returning decade in

modern market history, at least ignoring inflation (on a “real” basis, 1970 to 1979 was the worst). Yet, despite that hostile backdrop, the CGM Focus Fund, managed by Ken Heebner, racked up an 18% annual return. Wow, that’s fantastic, right? Actually, not so much…

While the average annual gains were indeed terrific, they were also extremely irregular. In fact, the fund incurred steep losses

for several years before rebounding spectacularly. Retail investors being, well, retail investors, did what they do so very well—they

bought high and sold low, pretty much along the lines of the simple graphic below, courtesy of Broyhill Asset Management. (See

Figure 9)

So, how much did this pattern affect their net returns? According to THE mutual fund authority, Morningstar, which tracked

when money was flowing into or out of the fund, the typical investor in CGM Focus managed to lose over 13% per year. Now, that’s some serious mistiming!

Yet, that was kind of a niche situation, and one that didn’t involve a wide swath of the investing population. But there was

another instance that did pertain to a major asset class (at least it was considered major a few years ago): Emerging markets.

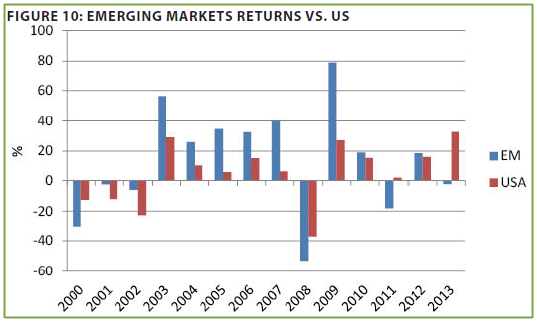

As you can see in the following chart, stocks from developing countries had a terrific run from 2003 to 2007, hugely outperforming a rising US market. Two years saw returns of 40% or more, and none were under 20%. Like the CGM Focus Fund, though, when they were cold, like 2000 and 2008, they were icebergs. (See Figure 10)

Consequently, when emerging equities were in one of their dizzying decline phases, most investors bailed out even faster

than they had entered. As a result, there weren’t many folks still hanging in there to enjoy the phenomenal 80% rocket shot that

followed the 2008 collapse.

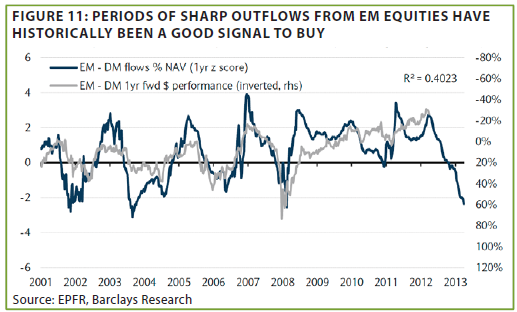

Figure 11 courtesy of Barclays from their February 11th report, Is It Time to Buy EM (Emerging Market) Equities?, compares the

difference between flows into or out of these markets and those of developed countries. When the blue line is high, investors are selling out of countries like the US and moving into emerging funds. When it is low, the flows are going the other direction. (See

Figure 11)

Additionally, Barclay’s shows the difference in performance between emerging and “emerged” markets in the year after the flows

are registered (note that the right hand scale is inverted). It should come as no surprise to avid EVA readers that extreme inflows

lead to poor future returns, while deep outflows lead to superior gains. (Even the well-timed in-flow surges in 2003 and 2005 were shortly undercut by material reversals.)

And then there is what we’re seeing today…

Inside the Fed—and our own psyches. Back in 2011, after the cumulative gain of 100% in just two years, as shown in Figure

10, the Evergreen investment team was frequently peppered with queries about why we had so little emerging market exposure.

We would then attempt to explain that we felt the best way to profit from the rapid growth in developing economies, especially

after the huge run-ups in their share prices, was to buy US blue chips that sold into those markets. Valuations were lower, and the

companies were generally of much higher quality, although they weren’t pure plays on the theme.

Suffice it to say, our response elicited yawns, howls of derision, and other dubious retorts. Being bullish on US stocks in 2010

and 2011 was not easy (and we wish we had been more bullish in late 2011!). Now, though, as is abundantly clear from the Barclay’s chart above, the money is flowing hard the other way: Into the US (as well as Japan and Europe) and away from the formerly idolized emerging markets. In fact, emerging market outflows so far in 2014 have exceeded the sum withdrawn during all of last year. Even more remarkably, they have now exceeded the amounts pulled out during the 2008 panic-to-end-all-panics (or so we hope).

It will come as no shock to any of our regular readers or more seasoned clients, but we are starting to nibble on stocks from the

developing world. Previously, our involvement was mostly via their bonds, which we felt was a safer way to play what has been a

volatile asset class (though, recently, less so). But volatility is a good thing when you’re coming in after big-time underperformance, and if you are prepared to add more on future weakness, as we are.

In stark contrast to the flight from emerging markets, investors have been charging into US stocks with increasing abandon—at

least until the market hiccupped a bit in mid-January, which, predictably, triggered outflows. But, overall, the long-running US bull market has made believers out of millions of Americans who would normally be highly skeptical of present US fiscal and monetary policies. There’s little doubt that, for the time being, the Fed’s almost inconceivable (unless you’re a Japanese central banker) flood of money into the financial system has carried the day—and the S&P to valuations unseen outside of very rare times in the past like 1929, the late 1990s, and 2007. (Do I really need to remind you of subsequent results?)

Just prior to Evergreen’s Annual Outlook event earlier this week, John Mauldin’s video production team very graciously offered

to film interviews with Louis Gave, Grant Williams, and, incredibly, yours truly (thank you, Ed D’Agostino!). They requested that we watch at least parts of the film Money For Nothing: Inside the Federal Reserve because they wished to get our reactions to its main message—essentially, the booms and busts that have occurred over the last fifteen years due to Fed actions (or, in some cases, inactions).

As many of you know, this is a topic near and dear to our heart, despite our belief that QE1 was necessary at the time, as was TARP (in fact, we believed the former was too timid). However, we also never believed it needed to be done with fabricated money. The Treasury could have issued debt to buy privately issued bonds and mortgages at bombed-out prices and almost certainly produced even larger gains for taxpayers than did TARP. (Newer EVA readers should be aware that we were among the few who believed TARP would be profitable.)

Frankly, much of Money For Nothing went over all too familiar ground for us, but I think anyone who is feeling complacent about

the current environment should watch at least the second half of the movie. It will certainly make you think, which is never a bad

thing, and given the way stock investors are behaving currently, it might be more important than ever. When we see headlines like

the one below, from a recent Wall Street Journal issue, I get very nervous—as should you!

To wrap up this EVA, it seems apropos to briefly quote Bill Nicklin, publisher of the popular financial industry daily Horsesmouth, and a highly successful veteran of the investment industry. Back in 2011, ironically, Bill wrote an article titled Humans Make Better Decisions Without Market Instability. In it, he wrote these resoundingly accurate words: “We are not genetically prepared for the instability of markets. We function better in stable environments.”

Bill is spot on: Our genetic predisposition is a terrible fit with an overarching and inarguable reality: Stock markets are wild,

erratic creatures. They rarely behave as they should, and their inherently feral nature leads to the kind of experience that investors have had with the CGM Focus Fund and emerging markets. This is precisely why we strive so mightily to protect our clients from the volatile ebbs and flows of unstable vehicles and asset classes. These mercurial investments often entice market participants into acting exactly wrong—buying when they should sell and selling when they should buy.

It is extremely challenging to stay disciplined when gains seem to be as recurring and plentiful as snowstorms on the east coast

this year. But, as Buffett has often said, successful long-term investing is simple, but it’s not easy and, we would add, especially at

times like these.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This report is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any securities mentioned herein. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. All of the recommendations and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions as of the date of this presentation and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal.

All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Information contained in this report has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, Evergreen Capital Management LLC makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness, except with respect to the Disclosure Section of the report. Any opinions expressed herein reflect our judgment as of the date of the materials and are subject to change without notice. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities,

financial instruments or strategies to particular clients. Investors must make their own investment decisions based on their financial situations and investment objectives.