“Monetary policy is not a panacea…Most of the policies that support robust economic growth in the long run are outside the province of the central bank.”

-Former Fed chairman, BEN BERNANKE (in the days before he went all-in on Quantitative Easing—QE)

This month’s Guest EVA is, in my opinion, a very special edition of our newsletter. First, the downside: It is much longer than what we normally “re-broadcast”. On the upside, however, I believe that this document from my close friend, Vincent Deluard, is one of best and most comprehensive overviews of the complex financial maze investors everywhere are attempting to navigate.

For those of you who simply don’t have the time to read the full letter, I’d suggest you scan the opening pages and then, if you’re interested, check out the conclusion. As someone who plows through about 1000 pages of research every week, another trick I’ve learned on speed-scanning longer pieces is to review the charts. If those interest me, I then read the accompanying text. However, I do believe for those who are baffled by the bizarre economic and market environment we find ourselves in these days, it’s worth taking the time to read Vince’s full opus, even if you break it down into a few sessions.

In several EVAs over the past few months, I’ve quoted Vincent and some of his work while he was at Ned Davis Research (NDR), one of our key sources of top-notch market analysis. However, Vincent—one of the smartest people I’ve ever met—recently departed from NDR and is now providing his astute insights from the San Francisco office of INTL FC Stone. The good news is that Vincent and I are still in constant contact.

One of the best aspects of this letter is that Vincent examines both the bull and bear case, starting with the latter. And, although his conclusion comes down on the bullish side, he makes a compelling argument for those of us who are anticipating a sell-off. In fact, I suspect many of you are going to feel that his bearish scenario is more plausible than the bull story.

Yet, I think it’s important to realize his bullish take could be right and we should seriously consider his rationale. It’s also critical to note that he believes there is a two-thirds chance of a correction this fall should complacency become too pervasive. It’s the Evergreen view that recent ultra-complacent readings on things like the Volatility Index (VIX) were proof positive that such a condition indeed occurred. Interestingly, the market weakness we’ve seen this month came right after those low anxiety levels were touched.

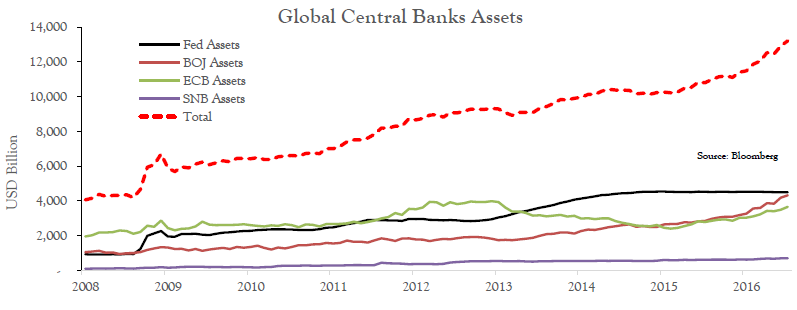

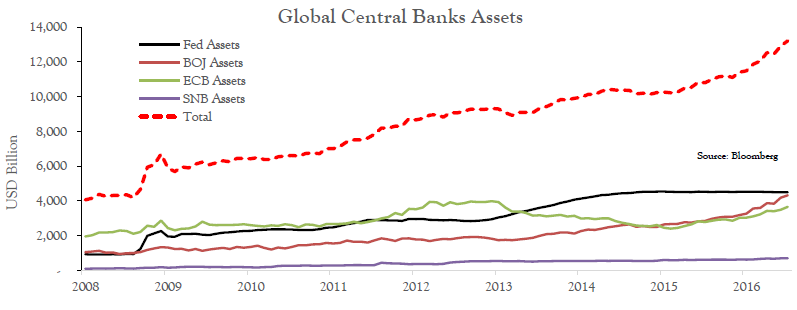

As much as I respect Vincent, there are several points I disagree with, the most important being the notion that governments have stumbled on a magical way to extinguish their sovereign debt via central bank purchases. He points out that the Fed and its counterparts in leading countries have fabricated $9 trillion (actually, $15 trillion if all QE-participants are included) to buy government bonds. He further observes this hasn’t created the high inflation that was feared when this process began back in 2008. His conclusion is that, therefore, QEs can continue to painlessly extinguish debt. Vincent has a lot of influential company advocating this as a miracle solution but I believe there is a fatal flaw in this logic.

In a nutshell, the Achilles’ heel is that the trillions the central banks have created to buy the bonds are essentially stuck in the global banking system. For sure, some of that has leaked into financial markets but, as has now been proven beyond a doubt, all that funny money has done precious little to help the planet’s economy. The reason is that velocity (the circulation rate of money in the financial system) has been falling as fast as the pseudo-dough (that would be pseudough for short) was created. So, either we continue to see more Japanese-like stagnation or, eventually, the trillions truly do begin to circulate, leading to virulent inflation, a condition always and everywhere devastating to financial markets (and human beings).

Another one of my quibbles would be with the idea that there has been deleveraging since the Great Recession ended. It’s true that the US private sector has paid down some debt (mostly through mortgage walk-aways, primarily from 2009 through 2012) but, as noted in prior EVAs, global IOUs have risen by a staggering $57 trillion in recent years. And, as Vincent points out, debt growth in China is astoundingly high, with very little economic growth to show for it.

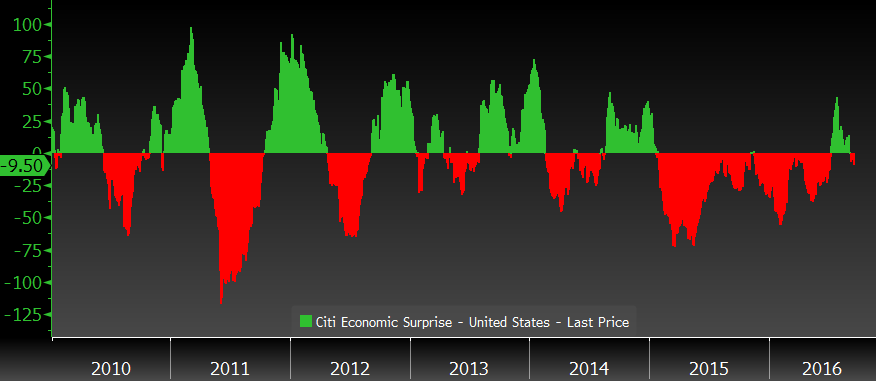

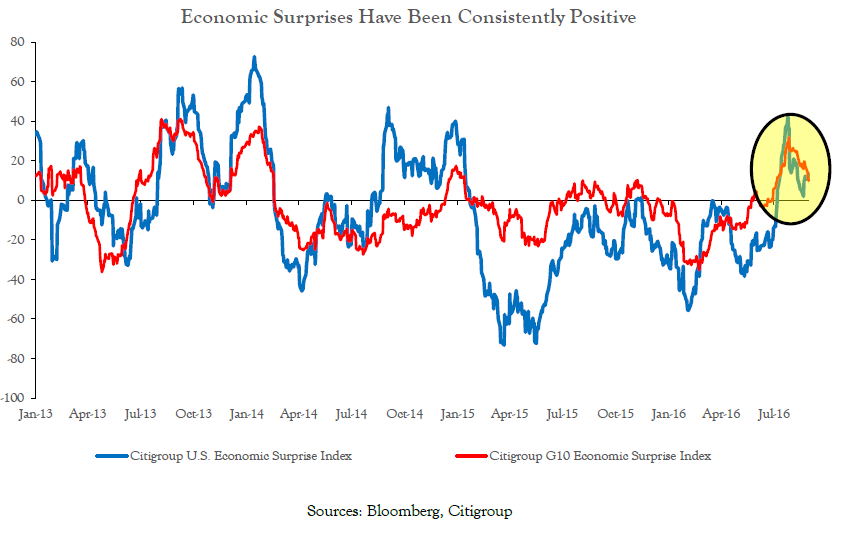

Lastly, the latest numbers on the US economy, including this week’s flaccid retail sales report, are calling into question his thesis that the long earnings recession for Corporate America is ending and that accelerating growth lies ahead. (The Citi Economic Surprise Index has also recently plunged back into negative territory.) But, as I’ve said numerous times before, the US economy is a Rubik’s Cube that continues to flummox most of us trying to ascertain its underlying vitality—or lack thereof.

Source: Evergreen Gavekal, Bloomberg

Source: Evergreen Gavekal, Bloomberg

Despite my areas of disagreement, I think all investors would be wise to consider Vincent’s theory of why we could see an explosive up-move in the market—once we get past the usual autumnal dislocations. But for all of you out there who have been yearning to hear why this bull run could have one more sprint left in it, please realize he stills sees this as a final surge by a nearly exhausted creature.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

By Vincent Deluard

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,

it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness,

it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity,

it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness,

it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair”

-CHARLES DICKENS, A Tale of Two Cities, 1859

Dickens’ opening line for “A Tale of Two Cities” is a good description of today’s curiously bipolar markets1. On the one hand, near-daily all-time highs on all major U.S. indices point to a bright and prosperous future. On the other hand, about twelve trillion of negative-yielding bonds foretell a plague of deflation, massive capital misallocation, and lurking black swans.

The bullish and bearish cases both have compelling arguments and there are plenty of pundits to plead for each case with absolute certainty on CNBC. When opinions are so divergent, and passions are running so wild, the best behavior is to listen without prejudice, distinguish the facts from the rhetoric, and assess the merit of each argument. This publication will attempt to carefully weigh the evidence for, and against, this seven-year old global bull market.

Unlike Narcissus and most economists, investors do not have the leisure to endlessly contemplate the sublime complexity of reality and hide behind the usual ambiguous “on the one hand … on the other hand” forecasts. The world’s most difficult questions need to be boiled down to a binary decision - buy or sell – and a binary outcome - win or lose.

After this careful review, we firmly believe that the weight of the evidence tilts towards the bullish case. From rich valuations to weak growth, shrinking earnings to policy uncertainty, China’s debt build-up to global demographic headwinds, there is plenty to worry about: one, or a combination, of these issues will eventually set the stage for a full blown bear market. However, the evidence to dismiss a secular bull market needs to be overwhelming, and so far, it is not. Instead, the greatest risk for investors is that the “New Normal” metamorphoses into the “New Crazy”, in one last euphoric buying mania.

Value investors are usually a grumpy bunch. If multiples are low, they complain about the economic environment, political risk, and earnings quality. If multiples are high, then they complain about the difficulty of finding reasonably-priced stocks, and fear that a bear (market) lurks behind every corner.

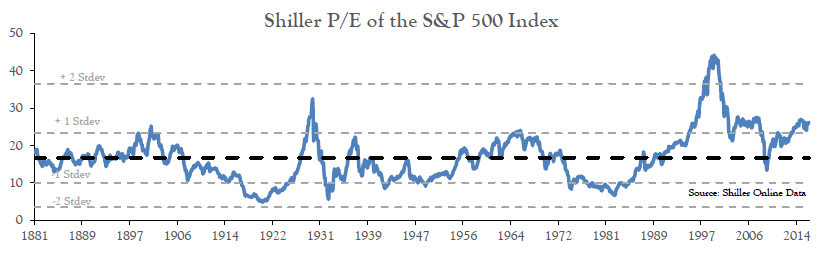

The current environment is uniquely painful for them, as stocks are priced for perfection in a world that is anything but perfect: based on the past five quarters of earnings, it is outright ugly. Discussions of valuation measures should start with the most respected indicator, the Shiller P/E. Smoothing over a ten-year business cycle, investors are paying 26 times inflation-adjusted earnings, a level that was only surpassed before the 1929 crash and the internet bubble.

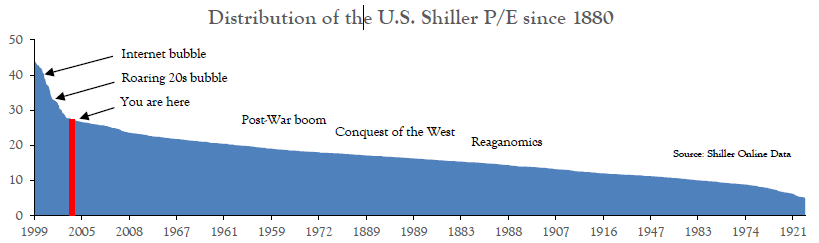

Viewed another way, the cyclically-adjusted valuations look outright scary. The current Shiller P/E would put the S&P 500 index in the 7th percentile of its historical distribution since 1881 – a period that encompasses the transformation of an agrarian economy into the world’s industrial and technological leader, the conquest of the West, the roaring 20s, the post-War boom, and the “new economy” of the 90s.

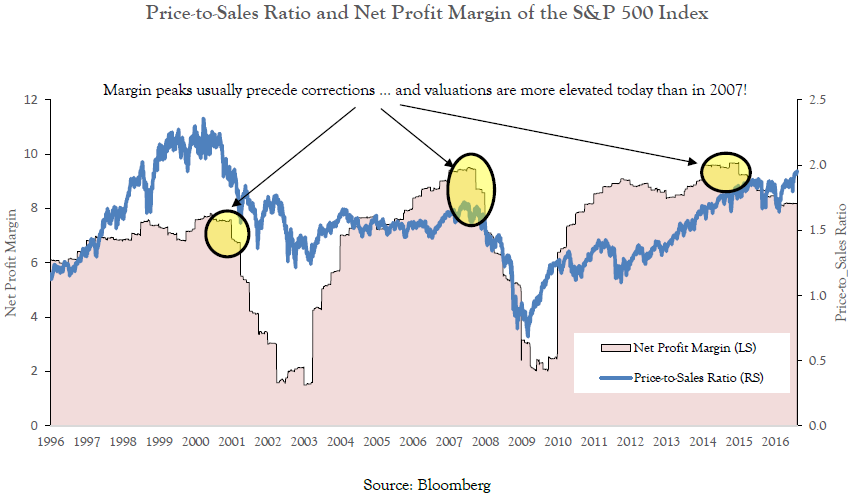

High valuations can be misleading when earnings are depressed: multiples frequently expand when margins hit a through, as investors expect better profitability after the downturn. This has not been the case in this cycle. Net profit margins are far above their long-term average, and the trend is down, not up: profit margins peaked in December 2014. The simultaneous erosion of margins and expansion of multiples, which are now above their 2007 peak levels, is historically unprecedented.

Breaking down the relation between margins and multiples can help us understand the drivers of this curious disconnect. The price of a stock index can be expressed as the product of sales, margins, and earnings multiples:

Price = Sales * (Earnings/Sales) * (Price /Earnings)

It follows that prices can only rise if (1) sales increase or (2) companies can squeeze more earnings out of each sale or (3) investors are willing to pay more for earnings. Based on recent margins trends, better profitability is hardly an option. Our earlier discussion of the Shiller P/E suggests that it is unreasonable to expect much more multiple expansion. This leaves us with number one, more sales, as the only engine to propel stock prices higher. To which we shall now turn.

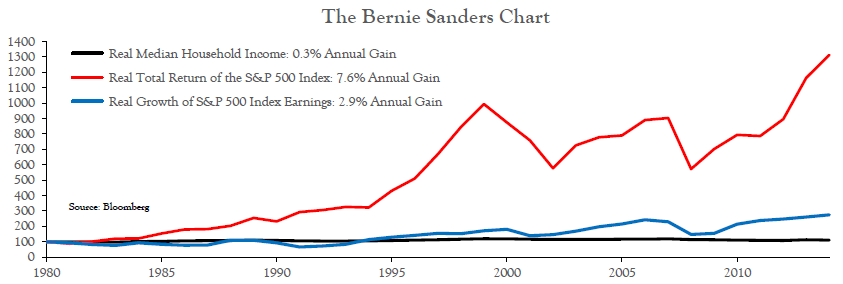

If I were to explain the rise of B. Sanders to a Martian who had never heard of the Vermont senator,2 I would probably show the chart below to summarize the divergent fates of the American manager, capitalist, and worker in the past 30 years.

Corporations and, by extension, managers have done very well. Real S&P 500 earnings per share have grown by an average 2.9% average earnings growth since 1980. That nice bump pales in comparison to the fantastic gains amassed by capital owners: adjusting for inflation, the S&P 500 index delivered annual total gains of 7.6%. But $100 ofhe median American worker has missed the party: his or her real compensation grew at a paltry 0.3% annually. These divergences compound over time: $100 invested in the S&P 500 index in 1980 would be worth $1,312 today, but $100 of median household income in 1980 has barely grown to $110 today.

Since wealth is a relative concept, the average American worker rightly feels that he has lost a generation of income gains. Economists can show very elegant demonstrations that free trade and deregulation actually help the poor, that technological change does not destroy jobs over the long-term, and that everyone benefits from innovation. But deep in their hearts, American workers would gladly trade Walmart’s everyday low prices, Chinese-made flat screen TVs, and time-wasting social networks for the stuff that was considered the staples of middle-class life in the 50s: affordable housing, employer-provided pensions, good health care, and college tuitions that could be paid by clerking at the local store for the summer.

This extraordinary capitalist accumulation may have led us into a dead end, or what K. Marx and the classical economists would have called a general product glut. Capitalism’s relentless pursuit of profits squeezes wages, which naturally reduces final demand, just as the economy produces more goods. As a result, capitalism needs to be constantly expanding to avoid collapsing on its own contradictions. In the 19th century, free trade, and eventually imperialism opened the new markets needed to absorb the goods produced by Western manufacturers. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the baby boom and the integration of women and minorities into the workforce expanded domestic markets. In the 1990s, the “great doubling” added China and the former communist bloc to the world economy.

These tailwinds are fading. Total fertility rates have fallen below the replacement level in most of developed world, and, more worryingly, in much of the developing world3 as well. Labor force participation has hit a plateau in most developed countries4. Most of the gains of free trade have already been harvested, and further liberalization is hitting formidable resistance among electorates on both sides of the Atlantic. Capitalism’s next “reserve armies” in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the subcontinent are far less productive than their Chinese predecessor. The populist tide in Europe and in the U.S. loudly demand a bigger share of the economic pie for workers: since that pie is no longer growing, that must mean that less will be left for the owners of capital.

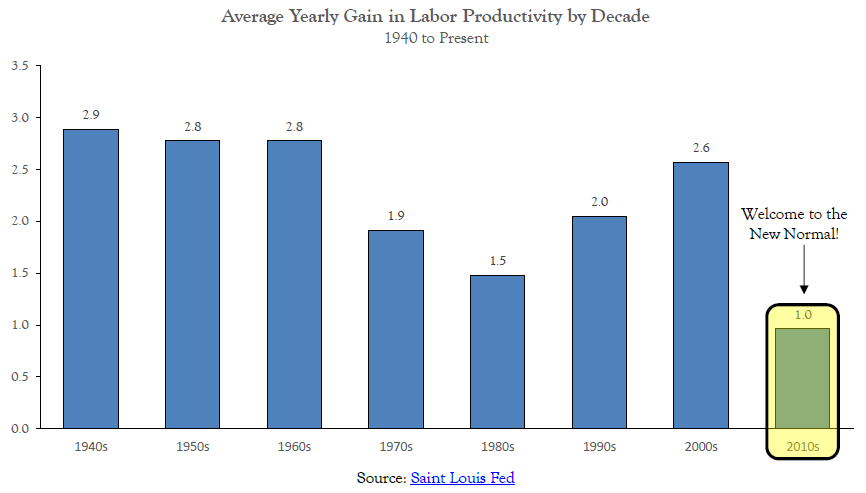

Does this Malthusian view of the world ignore the most important driver of economic growth – innovation? Sadly for future generations, productivity also seems to have hit a plateau. Annual productivity gains averaged 2.9% from 1995 to 2005, 2% from 2005 to 2011, and just 0.5% since 2011. Investors are aroused by the current strength of the labor market and big new job creations are cheered as proof that the much-awaited recovery is finally around the corner. But the dynamism of the job market is the result of the collapse of productivity to an abysmal minus 0.5% last quarter. Robots are taking over high productivity industrial jobs and basic services. Artificial intelligence is taking over formerly qualified positions in middle management. Most humans are eventually cornered into low-productivity service jobs: the largest job creations in this slow recovery were in healthcare, personal services, and the “gig economy” of Uber drivers (until they get replaced by self-driving cars).

In many ways, the bubble is already worse than its 2007 predecessor. I cannot resist the pleasure of pointing that the empty lot in Palo Alto shown below just sold for about $1 million. A million dollar does get you a house in the Outer Sunset, the least desirable and most foggy neighborhood in San Francisco. But as shown in the picture below, the lucky owner should budget a few minor repairs.

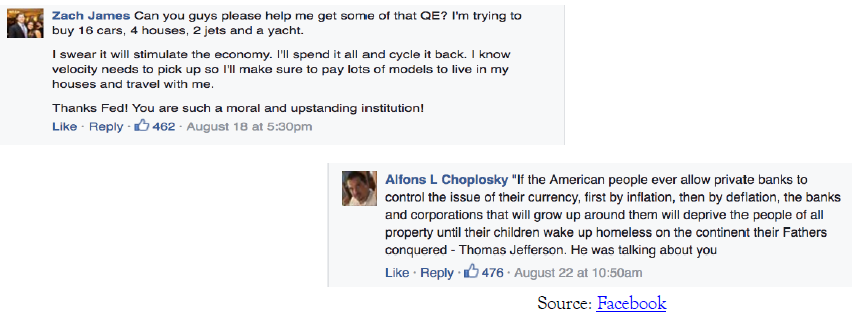

Teardowns selling for the price of mansions are by no means the monopoly of unicorn-filled Silicon Valley. From Stockholm apartments to Vancouver condominiums, central bankers’ global race to zero and below has inflated a housing bubble of massive proportions. Surely, the bubble has benefitted the lucky few who are fortunate to own properties in major metropolitan areas: that must be what central bankers call “the wealth effect”. However, for the vast majority of households, the “wealth effect” means unaffordable prices, sky-high rents, and eviction notices. It should not come as any surprise that the Federal Reserve’s naïve attempt to engage the public on its new Facebook page was overwhelmed with thousands of angry posts by disgruntled trolls.

In prior bubbles, investors could count on the “Greenspan (and then Bernanke) put” to bail them out of troubles. In 2001, A. Greenspan cut the discount rate for thirteen straight months, eventually stabilizing the market - and inflating a massive housing bubble. But where will tomorrow’s rate cuts come from? As the economic cycle eventually sours5, the Federal Reserve will be in the historically unprecedented position of fighting a recession without the ability to cut rates.

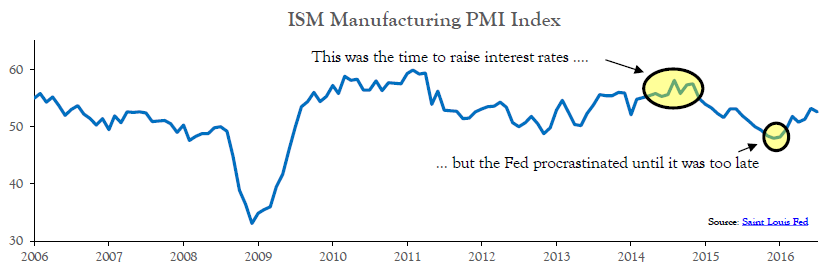

Looking back, late 2014 was probably the right time for a monetary tightening. Economic growth was strong enough to withstand one, or maybe two, hikes. Instead, the dovish Fed withered and delayed the hike until December 2015. By that time, the U.S. economy was already slowing and investors (rightly) threw a tantrum at the Federal Reserve.

Burnt once, J. Yellen learned her lesson: never do anything that may displease Mr. Market. A Federal Reserve that hailed transparency and forward guidance as its sacred principles is now changing its forecasts faster than M. Phelps can swim across a bath tub. Investors long wondered what data was monitored so closely by the Fed’s “data-driven” wonks. Now they know: it is the closing price of the S&P 500 index. Fed chairman W. McChesney Martin thought central banker should remove the punch bowl once the party got going: J. Yellen expects the drunk guests to ask her to close the bar.

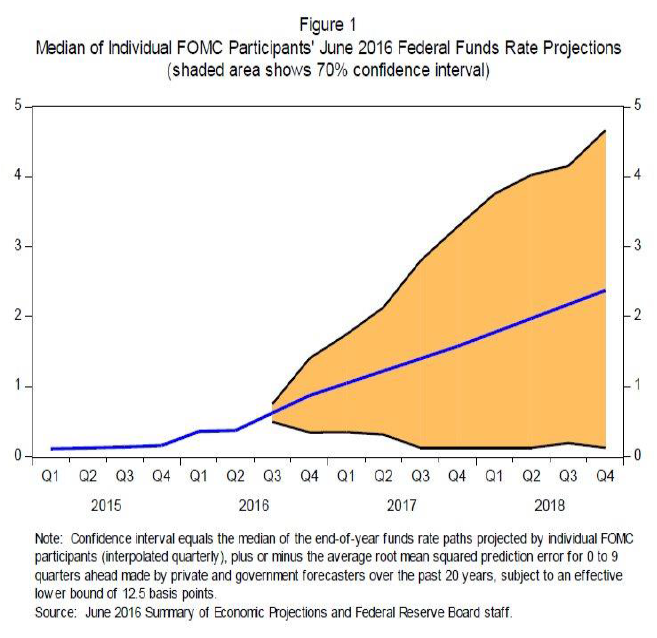

The Jackson Hole conference comically illustrated the FOMC’s new caution: the wise men and women of the Fed are 70% confident that the fed funds’ rate will be between 0.1% and 4.75% by 2018. If NASA’s calculations had been as vague, Apollo 11 would have landed on Pluto instead of the moon.

Burnt once, J. Yellen learned her lesson: never do anything that may displease Mr. Market. A Federal Reserve that hailed transparency and forward guidance as its sacred principles is now changing its forecasts faster than M. Phelps can swim across a bath tub. Investors long wondered what data was monitored so closely by the Fed’s “data-driven” wonks. Now they know: it is the closing price of the S&P 500 index. Fed chairman W. McChesney Martin thought central banker should remove the punch bowl once the party got going: J. Yellen expects the drunk guests to ask her to close the bar.

The Jackson Hole conference comically illustrated the FOMC’s new caution: the wise men and women of the Fed are 70% confident that the fed funds’ rate will be between 0.1% and 4.75% by 2018. If NASA’s calculations had been as vague, Apollo 11 would have landed on Pluto instead of the moon.

As usual, most central bankers are blindly following the Federal Reserve down the path of economic irresponsibility. Since we missed our chance to sober up, why not have another cup of the bubbly? In 2014, Chinese government economic plans were filled with concerns over excessive debt and capital misallocation. The Chinese politburo was seemingly ready to sacrifice its short-term growth targets to orderly deflate its massive investment bubble.

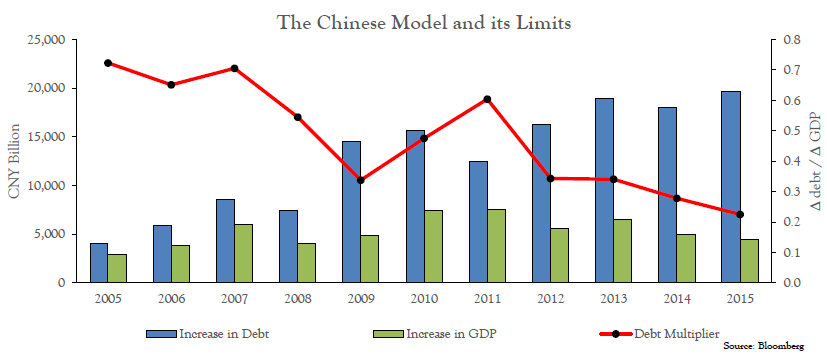

Alas, the temptations of a control economy are too great. In 2015, total Chinese government debt increased by a record CNY 4.6 trillion, or about $700 billion. But officials are getting far less bang for their (borrowed) buck: in 2004, one Yuan in new debt generated 73 cents in extra GDP. By 2009, this had fallen to 33 cents. Today, the ratio is less than 1 to 4 , i.e., debt is increasing four times faster than GDP, a clearly unsustainable speed. But according to economists and bureaucrats’ twisted logic, the failure of the debt-fueled growth model is interpreted as evidence that more debt is needed. Perversely, the fall of “debt multiplier” means that an ever-increasing amount of debt is required to achieve the same government-mandated growth target.

In Europe, “Brexit” has been the great enabler for more crazy central bank policies. Since no one knows what the ultimate effect of Brexit will be (especially since it may never happen), any economic data point can be used to justify all central bankers' decisions.

Is the latest economic release soft? That must be because Brexit is hampering growth: more easing is needed. On the contrary, is the economic data strong? This proves that central bank activism work: the positive impact of negative rates (!) must have offset Brexit headwinds. Surely, crazier policies are needed to consolidate these gains.

In the absence of Brexit, some economists and journalists may have eventually started an intelligent discussion on the unintended effects of negative rates and endless quantitative easing. But Brexit has created its own reality distortion field. The simple invocation of the word at a central bank conference can silence a room of journalists, and convince them that the policies that have not worked for the past seven years are more needed than ever.

Before I start the bullish case, I need to acknowledge the strength of the bearish arguments. Overstretched valuations, financially-engineered earnings, structurally lower long-term growth, the Chinese debt bubble, and out-of-control central bankers are indeed a scary cocktail. Add in the political risk of a very tight Italian referendum in the fall, a non-zero chance of a Trump comeback, and inflationary pressures leading to a return of the Fed-hike talk, and the stars would be aligned for a severe correction in the seasonally weak months of September and October. If the current mood of healthy optimism turns into complacency, we would put the odds of a fall correction at above two-thirds.

Hopefully, sentiment indicators and technical divergences would alert us of the correction. Realistically, past valuation corrections in this cycle (May 2013, September 2014, August 2015, January 2016) have been so fast that most investors did not have time to react until prices had fallen by 10% or more. The question would then become: should investors cut their losses to avoid another 2008 waterfall decline, or buy the dip? I would argue for the latter. Here is why:

The bearish case handpicks the most elevated valuation indicator in one of the world’s most expensive markets: the U.S. Shiller P/E. Despite Shiller’s Nobel prize, there is no fundamental economic reason for the ratio of equities’ market capitalization to their ten year inflation-adjusted earnings to remain constant. Four massive limitations of the Shiller P/E make it less relevant today:

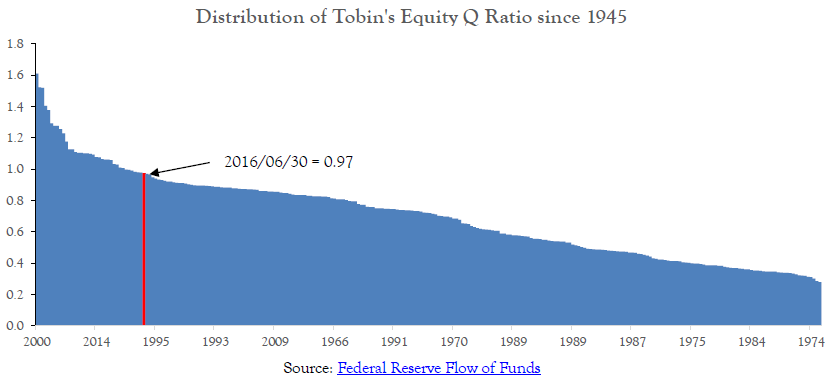

As far as valuations go, I prefer to use Tobin’s Equity Q ratio. First, because it has a better track record at identifying market cycles than the Shiller P/E7. Second, because Tobin’s Q reflects an economic arbitrage relation: over the long-term, the market value of corporate equities should equal the replacement value of their net assets - otherwise companies could be bought or sold in the market for an immediate profit. Tobin’s Q gives us a much more reassuring message: at 0.97, today’s ratio would put us in the 15th percentile of its historical distribution. It also remains below the theoretical arbitrage level of 1.0.

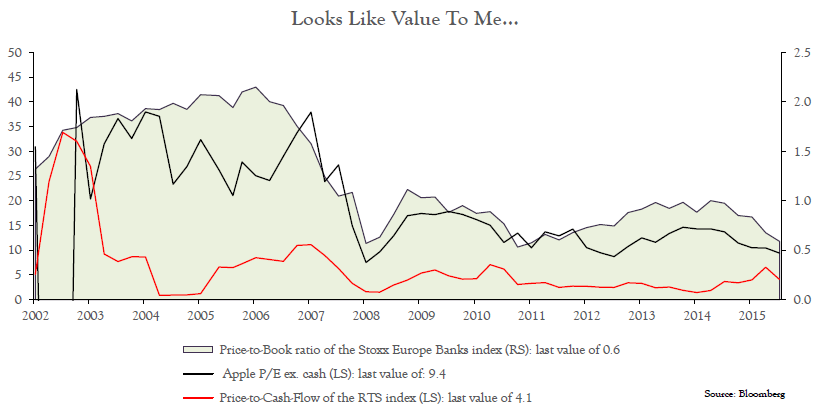

Second, this overvaluation is not pervasive. Many U.S. large caps are indeed very richly priced. European sovereign bonds and most of the world’s “safe” assets are obscenely overvalued. But investors just have to look outside of these areas to find value8. The Russian stock market Index trades for 3.9 times its cash flow. Even by Russian standards, that is cheap. The European bank index can be bought for less than two-thirds of its book value. Excluding cash holdings, the largest company in the world, which owns the world’s most admired brand, trades for 9.4 times earnings.

It is unfair to compare today’s isolated bubble to the general euphoria of 2007. GMO summarized the zeitgeist of these care-free days with their famous “everything bubble” quote: “from Indian antiquities to modern Chinese art, from land in Panama to Mayfair; from forestry, infrastructure and the junkiest bonds to mundane blue chips; it’s bubble time! […] Everyone, everywhere is reinforcing one another.”

Today’s bubbles are sporadic, not epidemic, and the market has proven its capacity to digest them. In fact, at least five contained bubbles already deflated without derailing the bull market: social media, exploration and production companies, mainland Chinese stocks, biotech and momentum stocks (FANG). There is no reason to think that the current bubble in “safe stocks” will not experience the same fate: rather than complaining about the high P/Es of the new “nifty fifty”, investors should pay attention to the recent rally and the dirt cheap valuations of material stocks, most emerging markets, and yes, European banks.

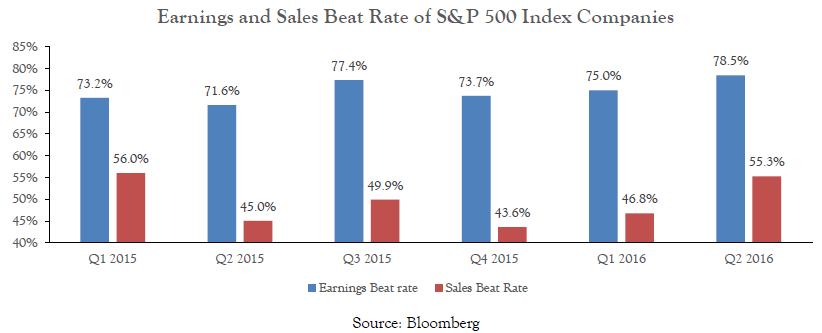

There is no hiding the truth that earnings have been awful in the past five quarters. But there are some signs of hope. 78.5% of S&P 500 Index companies beat earnings estimate this past quarter, the best score since December 2014. Even sluggish Europe managed a 60% beat rate, an improvement over the prior quarter.

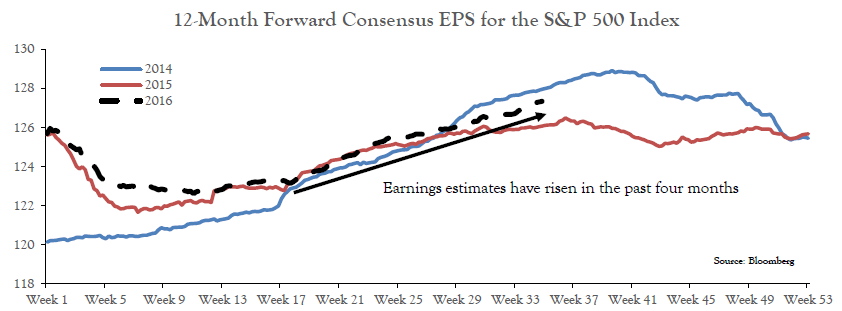

Buy-side analysts often scoff at beat numbers. It has become a Wall Street tradition to excessively lower guidance during downturns so that that bad reports can be hailed as “beating expectations”. Estimates duly dropped during the last quarters of 2014 and 2015, lowering the bar for year-end “earning beats”. But if this game was still going on, companies and analysts would be busy lowering their forecasts: instead, 12-month consensus earnings estimates have increased recently, suggesting that we are at a trough.

This uptick is confirmed by the Citigroup U.S. Economic surprise index: economic data has now surprised to the upside for 39 straight days, the longest stretch since mid-2014. Contrary to 2014, positive economic surprises are also recorded in most G-10 countries, suggesting that the recovery is finally broadening.

For now, we have addressed the bears’ two main short-term concerns: high valuations and falling earnings. What about the long-term concern of a new normal of low growth and excessive debt? To which we shall now turn.

I have always wondered how government statisticians can compute GDP growth with two-decimal precision, and marveled at the market reaction that such releases provoked. Anyone who has dealt with large datasets knows that measuring even simple things, such as the earnings of 500 large companies, is painfully difficult. Think about aggregating the value of all goods and services produced by an economy in near real-time! When I bring mustard pots from my hometown of Dijon back to the U.S., how do public accountants know to reduce U.S. GDP for this import? How does the Bureau of Economic Analysis collect data on the thousands of start-ups and small businesses that open and close every month?

At best, I can see how GDP statistics could capture the general direction of the economy in the ‘50s and the ‘60s, when growth meant “more stuff”. Economic growth was visible, and measurable, when the U.S. was building its interstate highway system, its neat suburbs, and glistening skyscrapers.

But today’s growth is no longer about “adding more stuff”: technological progress radically disrupts established industries. Following Moore’s Law, today’s basic microprocessors are 649 times more efficient than the most powerful mainframe in 1970. U.S. accountants use a “hedonistic” adjustment to correct for quality effects, but how can a qualitative breakthrough such as the jump from landlines to smartphones, be captured by some arbitrary divisor?

In the current era of disruption, stuff that we used to pay for has become completely free – the most radical form of technological deflation. I used to buy maps. I used to pay for stamps and paper. I used to pay for music. I used to pay a membership to my local library. I used to buy memory cards. I used to pay for dictionaries and translation software (they were awful). Now, I get all of that for free from just one company, Google. I vaguely realize that I am actually paying by allowing Google’s algorithms to analyze my search history, my spending habits, and every detail of my life. But I never thought that these things were worth anything while the things that I get in return have clear monetary value to me.

Much of the software industry is characterized by zero marginal costs: once a software is written, it does not matter whether it is downloaded once or a billion times. This goes against the basic principle of standard economic theory, the law of diminishing returns. The statistical tools that were built in that classical era cannot work in what Jeremy Rifkin called the “zero marginal cost society”9.

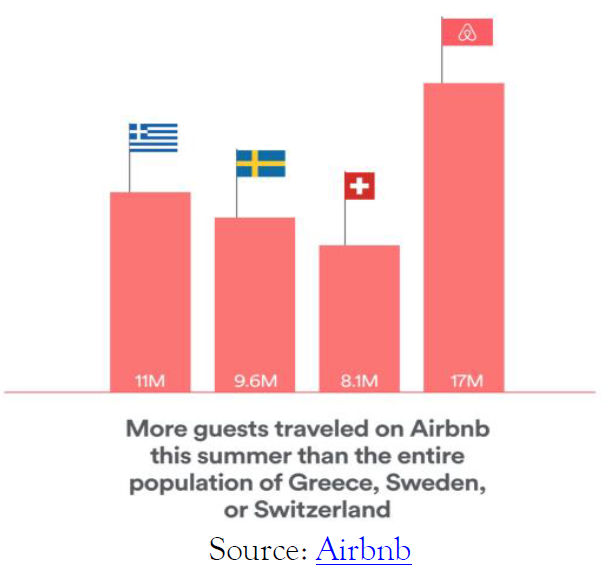

The sharing economy is another illustration of this theory. This summer, 17 million guests stayed in one of Airbnb's million plus listings. A new world record was broken on the night of August 8, 2016, with 1 million individual stays. In the world of yesterday, more than ten thousand mid-size hotels10 should have been built to accommodate these guests. That would have been enough to generate the big investment pick-up that economists so desperately await to jumpstart this sluggish economy.

Why am I subjecting my readers to this long and naïvely-technophile rant? Because GDP equals output times prices. If entire industries become free, it could very well be that nominal GDP drops at the same time as output rises. Economists should care about the real stuff, not the monetary veil. Yet, the current panic over deflation suggests that economists have forgotten this basic principle.

Whenever I make the argument that stuff getting cheaper, or free altogether, is a blessing, clients usually retort that deflation is a problem when debt is high. Because debt is labeled in nominal terms, it takes more real earnings to pay back debt during deflationary periods. Bankruptcies ensue, credit tightens, and economies get stuck in deflationary traps.

I find plenty of empirical and philosophical flaws with this theory. Outside of the Great Depression, there are few instances when deflation led to a contraction of real GDP. If anything, deflation was the norm during the Gold standard. The U.S. CPI dropped by half between 1871 and 1941, a period that witnessed the conquest of the West, the industrialization of the country, the building of the transcontinental railroad, and the tremendous accumulation of wealth of the robber barons.

Philosophically, the argument that “inflation-is-good-for-debtors-which-is-good-for-the-economy” essentially posits the “euthanasia of the renter” as the end goal of monetary policy. But how can Keynesian economists so loudly champion credit, and so deeply scorn savings? Are they not the same thing? And how could savers never realize that they are being systematically ripped off by stealth inflation?

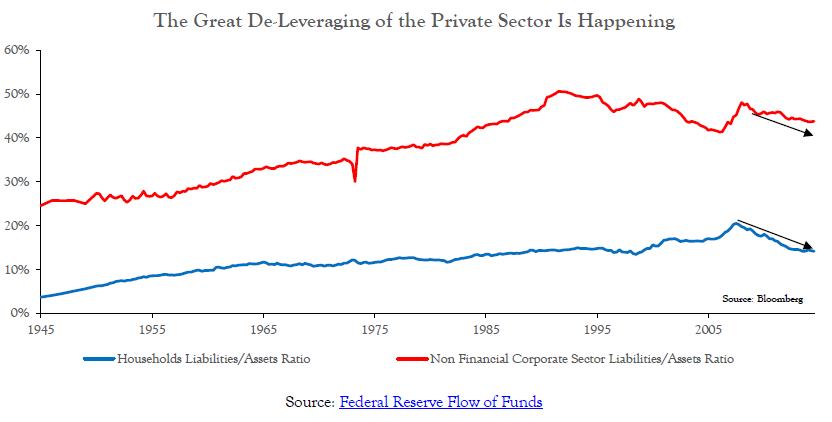

But my biggest issue is with the debt burden argument. First, because it rests upon the often-repeated notion that this recovery was built on an unsustainable increase in debt. This is simply not true: most of the developed world has de-levered since the financial crisis of 2008. The U.S. household savings rate is 6%, up from 2.5% in 2008. Total corporate debt represents 43.8% of U.S. non-financial assets, down from a 2008 peak of 48%. Despite all the bankruptcy fears concerning Deutsche Bank and Italian non-performing loans, European banks are much less leveraged today than they were in 2008. Corporate leverage ratios have remained extremely low in Europe, even though blue chips could (should?) have issued debt at zero rates to buy back their shares.

Since it is impossible to disagree with the reality that the private sector has deleveraged, the “debt burden” conversation usually focuses on towards public debt. The private sector may have de-leveraged, but governments have accumulated gargantuan amounts of debt since the great financial crisis. Surely someone will need to pay the bills?

This notion rests upon a fundamental misunderstanding of what debt is, and how quantitative easing works. Debt is the promise to pay interest when it is due, and the principal at maturity. When debt is held by a private investor, that is the end of the story. But things are very different when that security is held by a central bank. Take the example of the Federal Reserve, which is obliged by Congress to return any profit to the national Treasury11. The actual cash flows are perfectly circular: every six months, the U.S. government pays interest on the notes and bonds that the Federal Reserve holds. And at the end of year, the Federal Reserve writes a big fat check to the Treasury, for the exact value of the coupons it has received.

What about the principal? If the Federal Reserve allowed its holdings of governments securities to mature, there would indeed be a net outflow from public coffers. But it has not done that, and has never indicated that it was considering not reinvesting the proceeds of its maturing holdings, or “quantitative tightening”. In order to keep a constant balance sheet, the Federal Reserve needs to buy a new treasury for every bond or note that matures. From the perspective of the government, that means that principals can be rolled over indefinitely, and never repaid.

What does this discussion mean from a macro perspective? That the global government debt stock is grossly over-estimated when central banks holdings are included. From an economic perspective, central banks and national treasuries could simply cancel that debt12 and absolutely nothing would change for taxpayers.

Understanding the debt monetization cycle can change our perspective on the global economy because the amounts are gargantuan. The Federal Reserve owns about $2.3 trillion in treasury securities. The Bank of Japan owns $2.6 trillion in Japanese Government Bonds, more than the banks and insurance sectors combined. The Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, and the Bank of Japan have increased their balance sheet by about $9.1 trillion since 2008, mostly through purchases of government securities. That is $9 trillion that taxpayers will never service, and effectively never repay.

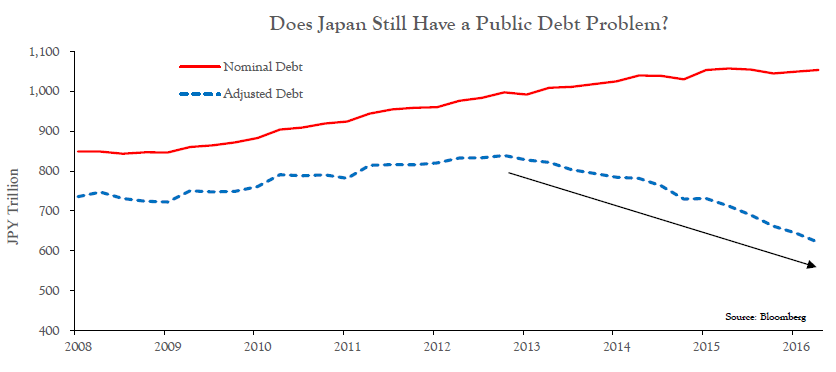

Quantitative easing programs have been so enormous that they have more than offset governments’ borrowing binges. For example, Japan has been running government deficits of close to 8% of GDP in each of the past seven years. Yet, this increase in debt has been more than absorbed by the Bank of Japan’s purchases: net of central bank holdings, Japanese public debt has actually shrunk by JPY ¥218 trillion since the start of QE (chart below). In addition, the Japanese government gets paid to borrow all the way up to 15 years13. The servicing cost of Japan’s net debt, which is the only thing that matters from a public finance perspective, is at a generational low.

This debt monetization mechanic has been fairly common throughout history: for example, the German Republic of Weimar has used, and overused, the Bundesbank’s balance sheet to monetize its post-World War I debt. The monetary financing of public deficits was the norm in most of Latin America and Africa for most of the past century. Yet, most economists refuse to acknowledge that the same process has vaporized about $9 trillion of developed government securities. The World Bank and virtually every financial newspaper still report the scary fiction that Japanese government debt towers at one quadrillion Yen, or 229% of GDP, and most portfolio managers are still convinced that the developed world is still stuck in a sovereign debt crisis.

My best explanation for this general incredulity is that we choose to deny a reality that conflicts with every principle we were taught, our sense of fairness, and our self-projections as “modern sophisticated economies”. Religion and law have imprinted the notion that debt needs to be paid back eventually, or defaulted upon. Our pride in our “advanced economy” status fools us into believing that only primitive governments use the printing press. It is too difficult to accept that sophisticated economists and respected central bankers effectively ape the policies of the Republic of Zimbabwe.

It is even harder to accept that governments and central banks got away with such a simple trick: standard economics theory posits that debt monetization always leads to inflation14. Yet, inflation is nowhere to be seen: the countries that have made the heaviest use of the printing presses, Japan and Switzerland, currently experience negative inflation of -0.4% and -0.2%, respectively.

From a contrarian perspective, our collective incredulity is extremely bullish. Much of the investing world is worrying about $9 trillion of debt that no longer exists. It may hurt our sense of logic, but the reality is that government deficits do not matter in the “New (deflationary) Normal”: in a fiat currency system, the only limit to debt monetization is inflation. If inflation runs below whatever target central bankers believe is optimal, and if the private sector is not willing to invest excess liquidity, governments get a free pass to spend as much as they please.

From an investing perspective, the debate of why this “debt monetization miracle” happened15, or whether it is good or bad, is irrelevant. It happened, and this is all that matters. The true enigma is why governments have not seized this opportunity to indulge in giant investment programs, or, more realistically, good old pork-barrel spending. The German government could get savers to pay interest to finance a complete upgrade of its public infrastructure, and have the European Central Bank slowly cancel its principal. Schäuble’s16 insistence on “schwarze null17” will look incomprehensible to future generations.

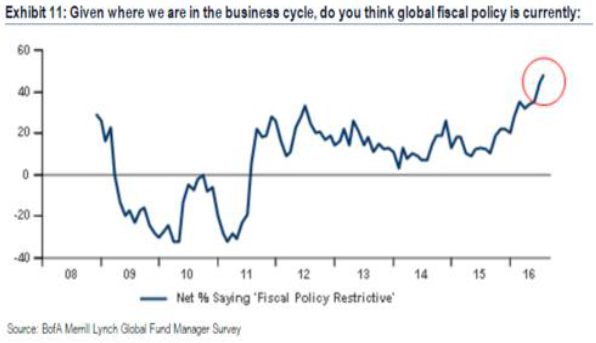

There are some signs that this extraordinary fiscal restraint is eroding. The last Canadian election was not just won on J. Trudeau’s boxing skills and charming smile, but also on the realization that public stimulus is a free lunch in a deflationary environment. In Japan, S. Abe doubled down on his trademark “Abenomics” with a $265 billion stimulus package last month. The economic program of both U.S. presidential candidates would also mark a significant break from the relative fiscal restraint of the Obama presidency.

The timing of this likely shift towards deficit-financed public investment is uncertain, but it hardly matters for equity investors.

If the surge of public spending is rapid, it will initially be greeted with enthusiasm by investors: the latest Bank of America / Merrill Lynch institutional survey shows that a record number of managers are demanding more public spending. What about the eventual inflationary hangover from such a spending binge? Initially, it will be hailed as a sign of our triumph in the global war against deflation. Growth expectations will duly increase, dragging interest rate in their joyful ascent. Would rising rates derail the equity rally? Probably not: by then, higher rates will no longer be seen as a threat, but as a proof that “this is finally working”.

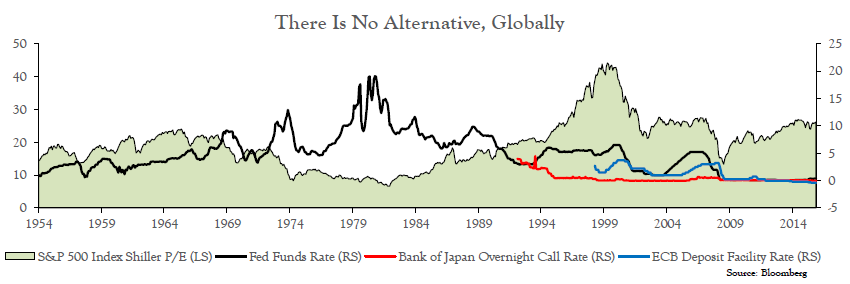

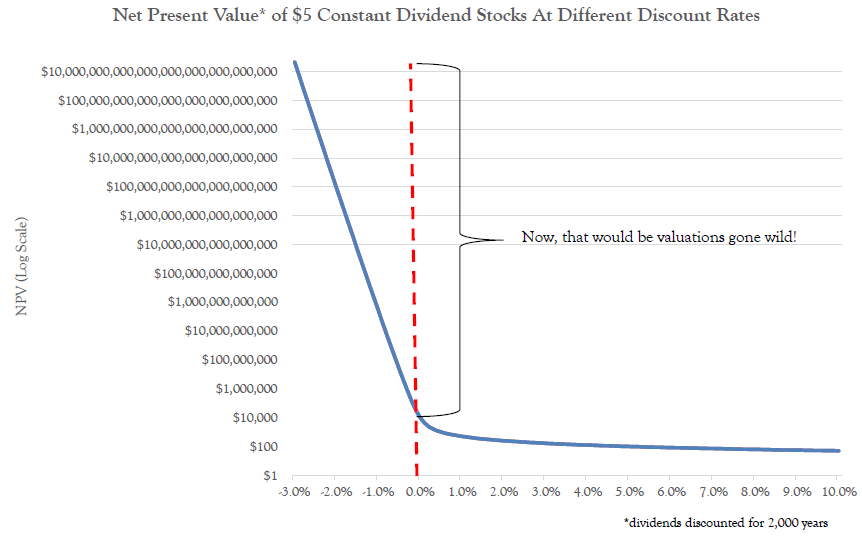

What if we are wrong? What if political roadblocks stand in the way of our predicted tsunami of public investments? Fear not, equities would rally too. The need to fight deflation would prompt central banks to announce ever greater quantitative easing packages. This increase in the demand for government bonds without any increase in supply could squeeze an already tight market. Negative yields would continue their cancer-like propagation throughout the developed world. A negative yield on the U.S. 10-year treasury note will be a much bigger problem for managers to worry about than a Shiller P/E of 26 on the S&P 500 Index. More than ever, equities would be the “There Is No Alternative Asset”.

The effect of persistently negative rates on equities’ valuations is almost incomprehensible: with a negative discount rate, any cash flow producing equity is theoretically worth infinity17. The chart below shows the net present value of 2,000-year stream of $5 dividends at different discount rates. At a negative discount rate of -3%, this $5 dividend stock would be worth 47,684 trillion trillions. Welcome to the new crazy!

1 This bipolar disorder has spread to U.S. politics: the Republican and Democratic National conventions last month depicted two radically opposed realities, and seemed to address to completely different nations.

2 I did not mention D. Trump because the Martian would surely have heard of real estate tycoon, steak entrepreneur, reality TV star, and Miss World philanthropist.

3 China’s total fertility rate has fallen to European levels of 1.66, and Iranian women have less than 2 kids over their lifespans.

4 For example, the U.S. labor force participation rate has fallen from 66.4% in 2007 to about 62% in August 2016. The drop is particularly impressive for white men: the Atlantic estimates that 10 million prime age men have gone missing from the labor force.

5 Profit margin trends suggest this may have already happened.

6 J. Siegel, The Shiller CAPE Ratio: A New Look, Financial Analyst Journal, Vol 72, No 3, May/June 2016

7 This will be covered in an upcoming publication

8 As a personal anecdote, I was recently invited to speak at a pension fund panel in London. The morning session was spent complaining about negative yields, high valuations, and the death of fixed income. I tried lightening up the mood by mentioning that most emerging markets were quite cheap, and that European banks traded for pennies on the dollar. I was abruptly reminded that I did not understand “governance risk”. When I pleaded guilty to the charge and asked for an explanation, I was told that governance risk really means career risk: no one loses its job for buying German bunds, regardless of their yield – or lack thereof.

9 J. Rifkin, The Zero Marginal Cost Society, St. Martin’s Griffin, 2015.

10 Assuming an average of 100 rooms per hotel and 100% occupancy rate

11 The same is true in Europe, but the process is complicated by the existence of “capital keys” guiding the allocation of ECB profits to individual member states.

12 A more complex solution, such as swapping central banks’ treasuries for a non-interest-bearing perpetuity might be easier politically, and achieve the same objective.

13 Swiss Government Bonds have gone into even deeper negative territory, with 50-year bond auctions pricing below zero.

14 M. Friedman was so convinced that “inflation was always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” that he had Fisher’s equation (MV = PQ) engraved on his license plate

15 Most economists attribute deflationary pressures to demographics, lower commodity prices, and technological progress. I believe the latter cause is dominant.

16 German Finance Minister

17 The requirement that the German public balance be zero or a surplus.

18 When the discount rate becomes negative, the theoretical net present value of a stock rises exponentially, as each discounted cash flow is worth more than its predecessor.

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.