“There’s a huge layer of the economy unseen in the official data and…unaccounted for on the income statements and balance sheets of most companies. Free digital goods, the sharing economy, and changes in our relationship have already had big effects on our well-being.”

-ERIK BRYNJOLFSSON and ANDREW MCAFEE, authors of The Second Machine Age

The PM Who Knew Too Much. In the investment business, PM doesn’t stand for the time of day between noon and midnight. Nor does it mean prime minister. Rather, it’s short for portfolio manager.

It’s been a thankless job in recent years for the most part, even among many of the money management industry’s most illustrious practitioners. Prior EVAs have shared how tough 2015 was for a long list of super-stars and, according to the estimable James Grant (author of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer), 2016 is another stinker (knock on a lumberyard of wood that this continues to be a strong year for Evergreen portfolios). Index, or passive, vehicles have been largely the place to be and they have attracted vast in-flows—often at the expense of their “active” counterparts. The recent failure of thinking PMs to cope with an investment world that seems totally misaligned relative to punk economic growth, rapidly mounting debt levels, and soaring social malaise, is causing active managers to feel, in the words of this month’s Guest EVA author, downright “surly”.

Jordi Visser, who wrote the highlighted treatise for this EVA—“The Art of Unlearning”—is no up-in-the-ivory-tower academic egghead. Rather, he is a PM himself, as Chief Investment Officer of Weiss Advisers, LLC, one of the oldest and most consistently successful hedge funds extant. Jordi penned his intriguing piece back in June and I must plead poor judgment in having read it just recently. As you will soon see, it’s a much more up-beat take on present circumstances than my outlook--which is precisely why I wanted you to see it.

You will also notice that it’s longer than what I typically write and my intent was to edit it down. But I didn’t think I could do so without harming its flow and message. Therefore, let me attempt to hit his high points for those that don’t have time to read it in full.

Jordi’s big-picture views are largely in-line with those of some of the younger members of the Evergreen investment team. And it may surprise regular EVA readers to learn that I actually agree with much of this perspective. Now, before you pass out, there’s more to that comment. To me, it’s like looking only at the asset side of a balance sheet. The assets he listed above are all valid but then there is the liability side, made up of equally intangible—yet meaningful—negatives like the increasing drag from government regulations gone berserk, an increasingly hostile view of the private sector by the public sector, and the deleterious impact of zero and negative interest rate policies, just to name a few.

But maybe I need to do some serious unlearning of what I’ve come to know over the course of my career. Maybe we can continue to have the S&P 500 trade at its highest median price-to-sales ratio ever at the same time that long-term profit growth prospects continue to decay. Or perhaps the best compromise is to continue tilting equity exposure to the best-positioned emerging markets, trading at much lower valuations than the priced-for-utopia S&P. That’s a plan I can learn to live with.

*Lately, rates have been moving up and definitely throwing ice water on some of the hottest areas of this year’s market, including one of Evergreen’s preferred areas, MLPs (Master Limited Partnerships).

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

By Jordi Visser

“Over time each chess principle loses rigidity, and you get better and better at reading the subtle signs of qualitative relativity. Soon enough, learning becomes unlearning. The stronger chess player is often the one who is less attached to a dogmatic interpretation of the principles. This leads to a whole new layer of principles—those that consist of exceptions to the initial principles. Of course the next step is for those counter-intuitive signs to become internalized just as the initial movements of the pieces were.”

-JOSH WAITZKIN, The Art of Learning

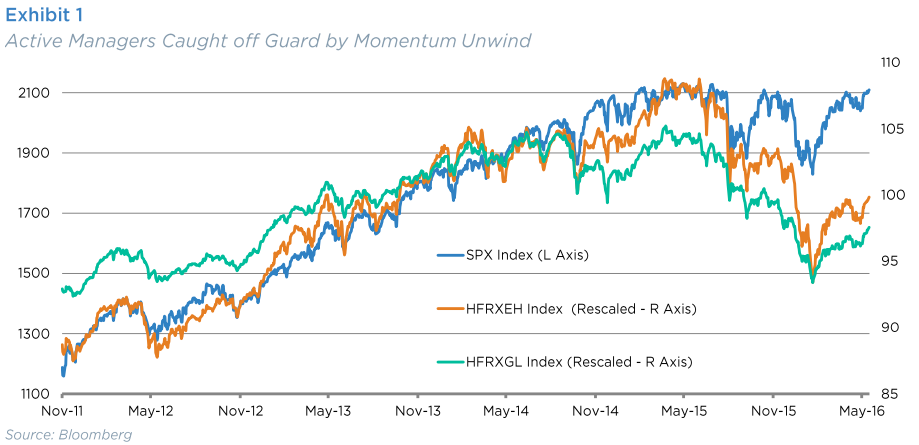

Historically, I’ve written papers when I felt there was something having to do with the markets or the economy that, in my opinion, differed from the consensus. After all, why write about your views if they cannot add value to people’s thoughts by providing another angle? Since writing the "Hagler vs. Leonard: A Unanimous Decision for Emerging Markets" paper back in February on my faith in emerging markets, much has changed in the markets. Stocks, credit and commodities have rallied and the dollar has weakened while global rates have done very little. For asset prices, there has been repair and a reversal in what had been strong trends since 2014. For the global economy, however, not much has changed. There have been some minor cyclical improvements, yes, but overall the same structural worries about the economy persist. Because of this, most view the asset repair as temporary because it lacks the “fundamental” support of growth and valuations. Another reason the recent bounce is being viewed as temporary is likely related to performance. The sudden shift in momentum earlier this year left many active managers caught off guard, as illustrated in Exhibit 1, which shows the SPX vs the HFRX Global Hedge Fund index and HFRX Equity Hedge index. With no fundamental reason for the momentum shift and the resulting underperformance, if I had to find a word that best describes sentiment of active managers today, I would use surly.

“Change is inevitable, and when it happens, the wisest response is not to wail or whine but to suck it up and deal with it.”

-DANIEL PINK, A Whole New Mind

At the same time that active managers seem surly, longer term asset allocators seem confused. Over the last couple of months, I have done a lot of traveling and spoken with many large asset allocators. These conversations have highlighted this confusion. The confusion is centered on what the future holds. Consultants, fund managers and strategists alike are all painting a bleak picture of forward returns due to the combination of low growth and high valuations. At the same time, central banks are being blamed for manipulating markets and pumping asset prices, fears over China, central banks having limited ammunition, negative rates, weak growth, risky credit and stagnant earnings all remain. What’s most shocking, given these fears and the current psychology of investors, is the fact that asset prices sit near all-time highs. We can all identify times over the course of the last 25 years when despite the presence of slow growth, high valuations and ineffective central bank policy, investors could always come up with some sort of reason to be optimistic about the future. Even in the summer of 2008, just weeks before Lehman, with financial companies disappearing by the week and the equity and housing market falling, all Warren Buffet had to do was lend a company money and everyone would talk about how cheap everything was and hope would come racing back.

This time the psychology is different. There is a malaise. But what could be scarier than what we witnessed in 2008? In the conversations I’ve had over the last few months, it feels to me like many investors seem to gradually be coming to a realization that what they think they know may no longer matter. It appears to be a feeling of being trapped in an investing world that no longer makes sense. It’s as though they feel trapped waiting for something logical to justify buying assets at these valuations without the safety net of the central banks whose net is no longer sturdy and with a market that no longer offers the available liquidity to enable you to exit if you are wrong. Positions get more crowded due to fewer growth stories and the fact that technology has brought transparency to good ideas, allowing anyone with a smartphone to find those hidden investment gems. At the same time, ETFs and algorithms give managers something to blame for increased correlations. The notion that everything we thought we knew about investing successfully may be changing is leading to frustration. All investors are looking for solutions. Perhaps the biggest reason behind the trap psychology though is the inability to hide safely anymore. In the past, if stock market valuations were viewed as high and the economy and earnings were viewed as weakening, you could move to cash. The average 3-month bill before the last three economic downturns in 1990, 2000 and 2007 was 6.5%. You got paid 6.5% to sit on cash. Now you get paid 25 bps (0.25%) while you hope that either the markets get to the level that “makes sense” again or economic growth accelerates. And although hope is not a strategy, in my opinion, all hope is not lost. This paper will attempt to provide a more optimistic outlook on future growth and market returns. It will focus on progress.

Today, progress is everywhere due to technological innovation. Progress, however, is not something you can easily measure. For growth, we have an index, GDP, to use as a measurement. Simon Kuznets led the team that developed the index in the 1930s during the Great Depression. In his report to Congress in 1934, Kuznets stated “The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income.” Eighty years later, despite Kuznets' warnings, this index is the focal point for much of what we worry about. But during this time of rapid progress, it may be time to take a closer look at the difference between growth and progress and think about how markets may reflect progress.

“The last few decades have belonged to a certain kind of person with a certain kind of mind- computer programmers who could crank code, lawyers who could craft contracts, MBAs who could crunch numbers. But the keys to the kingdom are changing hands. The future belongs to a very different kind of person with a very different kind of mind- creators and empathizers, pattern recognizers, and meaning makers. These people- artists, inventors, designers, storytellers, caregivers, consolers, big picture thinkers- will now reap society’s richest rewards and share its greatest joys.”

“We are moving from an economy and a society built on the logical, linear, computer-like capabilities of the Information Age to an economy and a society built on the inventive, empathic, big-picture capabilities of what’s rising in its place, the Conceptual Age.”

-DANIEL PINK, A Whole New Mind

To start down this journey of attempting to bring back some hope and optimism, it is important to frame the tone of the message. This is an attempt to explain how an argument can be made to be positive. It is not meant to be a debate. The reasoning behind why stocks are overvalued, how the central banks can no longer create growth or how China and emerging markets are filled with debt and structural issues are solid and factual. My goal with this paper is not to debate this reasoning but rather how to look at it in a different light.

At the end of the day, whether you are an active manager living hour to hour or an asset allocator with a liability to meet, we all have a job to do and that is to invest and provide a return. Presumably, when you encounter a problem doing your job, you look at all possible sides for a solution. And sometimes, like with a riddle, to solve a problem you need to get past your cognitive biases. The excerpt above is from A Whole New Mind by Daniel Pink which was published in 2005, two years before the iPhone came to the market. Since I first read this book, I have tried to incorporate this philosophy of a world that looks different going forward and not get caught being a linear thinker, extrapolating the past. There are very powerful and thought provoking messages in this excerpt that have stayed with me over the years. In 2013, I wrote a paper called "Adapt or Die: An Investment World Driven by QE, Tweets, Clouds, Robots, Singularity and Luddites" where I referenced the impact a senior official in the Air Force had on my thinking, changing it forever. He suggested I spend time on singularity theory and unlearn what I had learned. Daniel Pink did not refer to singularity theory, specifically, in A Whole New Mind but he did describe the world as changing rapidly in a “seismic- though as yet undetected-shift” and the impact that it would have on the economy, the concept of growth and what type of thinker would benefit from it. This is where I think the power of unlearning cognitive biases fits.

The concept of unlearning has fascinated me ever since I read The Art of Learning by Josh Waitzkin. In it Waitzkin writes, “The stronger chess player is often the one who is less attached to a dogmatic interpretation of the principles.” I keep coming back to that line when I consider the recent market sentiments emanating from some of the best minds in the history of investing. Maybe the sentiment represented being “attached to a dogmatic interpretation of the principles.”

“But as the economy has changed so, too, must our metrics. More and more what we care about in the second machine age are ideas, not things—mind, not matter; bits, not atoms; and interactions, not transactions. The great irony of this information age is that, in many ways, we actually know less about the sources of value in the economy that we did fifty years ago. In fact, much of the change has been invisible for a long time simply because we did not know what to look for. There’s a huge layer of the economy unseen in the official data and, for that matter, unaccounted for on the income statements and balance sheets of most companies. Free digital goods, the sharing economy, intangibles and changes in our relationships have already had big effects on our wellbeing. They also call for new organizational structures, new skills, new institutions, and perhaps even a reassessment of some of our values.”

-ERIK BRYNJOLFSSON and ANDREW MCAFEE, The Second Machine Age

One of these principles is the economy. It is difficult for anyone to argue that economic growth is good based on the measures we use. Last year, I wrote a paper talking about the likelihood of a recession and I believed by the end of the year, we had one. Whether it will be regarded as a recession by the National Bureau of Economic Research (“NBER”) in future years really does not matter. There were many signs of a recession visible in the industrial production side related to the oil industry and in company profits. I completely agree that GDP is weak and believe it will remain weak in the years to come. But although GDP has been weak since 2010, at the same time there has been tremendous innovation. The impact of this innovation on the economy is difficult to measure. The except above from The Second Machine Age describes the difficulty. In July 2013, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis announced revisions to GDP going all the way back to 1929. The largest change was due to the reclassification of R&D from an expense to an investment. It also included a change to intellectual property as long-lived assets. In 1999, software was reclassified as an investment. Last year, one of the leaders in the movement of readjusting the way we measure GDP who I referenced in the 2013 "Adapt or Die" paper, Brent Moulton, received the Julius Shiskin Award for Economic Statistics for his work in the area. There have been multiple books in recent years on the topic as well as a recent article in the Economist entitled "The Trouble with GDP". Diane Coyle, author of GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History, stated within a report to the UK government this year:

“It is clear to me that traditional measures of productivity cannot adequately capture the economic impact of the sharing economy, in part because GDP figures do not take into account economic benefits such as time saved, increased choice and lower cost of products—all of which are key consumer benefits of using the sharing economy.”

There can be little dispute at this point that the calculation of GDP was made for a time dominated by the physical world. As we entered the digital world with a sharing economy, and headed more and more into a virtual world, the relevance of GDP the way it is calculated will continue to decline. This is when the question of the difference between growth and progress becomes so important. Are measures like debt to GDP, productivity or stock valuations relative to GDP as important as they once were? If GDP is a less reliable measure, should we use it for investment decisions as we had in the past? This is where the unlearning becomes important because this goes at the core of what many of us have been told to be true.

“The illusion that we understand the past fosters overconfidence in our ability to predict the future.”

-DANIEL KAHNEMAN, Thinking, Fast and Slow

At the end of the day, GDP is an index which attempts to attach a number to the economy. Since the Great Recession, this index has become more and more important to the way people think about investing. Not that long ago, most people couldn't care less about whether GDP was 2.5% or 3.5% if we were creating jobs and inflation was in check. However, now it matters and a lot of that has to do with pure math. The movie The Big Short seems to have people following a line Dr. Michael Burry said to his investor in the film. “I’m not certain you understand this trade. This is a certainty.” Currently the view is stocks can’t go much higher from here because the multiple is too high (math), earnings growth is too low (math) and GDP cannot grow (math). We hear about China outflows (math) and the size of China debt (math) and so on and so on. We have been taught to be arbitrageurs in a linear inefficient world where there was an edge in using math to figure out the future. We were card counters. I think the problem is that the rules of the game have changed. Now, because of exponential innovation, the world is changing at a non-linear pace with less inefficiencies every day. Less inefficiencies means less certainty in investment outcomes. Less certainty and less fundamentally justifiable (math) opportunities leads to surly and confused investors being forced to unlearn. Unlearning is more difficult that finding blame and in this case, the blame seems to be thrown in the direction of factors, algorithms, ETFs and central bank manipulation. The reality is investing has been, and always will be, about predicting the future but in a linear world we hunted for certainty. The greatest investment opportunities that I remember came at times when it made the least mathematical sense. GDP was negative and the US lost five million jobs in 2009 when the SPX was up 26%, kicking off what has been, so far, seven consecutive years (and up for the 8th YTD). If Daniel Pink is right and number crunching becomes less useful, card counting will remain frustrating. For what it is worth, Dr. Michael Burry was recently quoted in an article saying, “I just did the math. Every bit of my logic is telling me the global financial system is going to collapse.” Maybe Dr. Burry is right again and it is that simple and we should just do the math, but something tells me, it may be important to look beyond the math.

“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefor all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

-GEORGE BERNARD SHAW

If the GDP and growth are math, what is progress and how do we measure it for investing? Progress is what has interested me over the past few years. I continue to believe it is more important to visit Silicon Valley and listen to people talking about what the future will look like than to focus on how we will get GDP to get us out of this debt problem. Initially, the way I thought about progress and investing was trying to figure out what sectors would benefit the most. However, as we learned with innovation in the energy sector, progress brings money and new players into a space, but also creates disruption to the incumbents and even eventually the younger companies. The more money you throw at a problem, the more intense the competition. Eventually, the pricing falls so fast, the disruption is as widespread as the initial excitement. At the market level in terms of assets, my focus has shifted away from finding the winners, which is getting more and more difficult as the innovation speeds up. The barriers to entry have never been lower thereby allowing intense competition. What was once dominated by ideas emanating out of Silicon Valley has now gone global. Just look at the recent Kleiner Perkins Internet Trends presentation and see the increase in smartphone and internet usage and think about how many more potential innovators there are in the world each day. More innovation and competition continues to drive down pricing. We are getting more and more efficiency. With lower prices, larger companies without the historical benefit of high and consistent top line revenue growth seen in the 1990s are being forced to focus on operating expenses (OpEx) rather than capital expenditures (CapEx). Chuck Robbins of Cisco at a conference in October 2015, said their customers, for the first time ever, were more concerned about OpEx than CapEx. This should worry anyone focused on GDP and growth. However, forcing established businesses to be run more efficiently is progress. This argument is made in the excellent book Harvesting Intangible Assets where Andrew Sherman shows examples of how some of the largest companies have been able to leverage their intangible assets into less waste. The example of less waste can also be seen in zero based budgeting. Zero based budgeting is a concept getting more and more press these days due to the success 3G Capital had in their aggressive cost cutting work with Kraft and Heinz. In looking at the 3G success with those companies, the real question is why management of those companies was not able to cut waste themselves. This is again where unlearning comes into play. The hierarchical corporate structure, inflexible leadership at levels and a belief in their historical principles makes change difficult without unlearning. For 3G, this is what they do so there is not unlearning. They look for situations where they can find waste. Progress is about efficiency and reducing waste. We all known governments and large corporations are filled with waste. Andrew Sherman puts the number at 10-30 trillion dollars. In 2013, McKinsey Global Institute put out a report titled "Disruptive Technologies: Advances That Will Transform Life, Business, and the Global Economy". In that reports, they specify 12 disruptive technologies and the impact they will have in dollars on the economy by 2025. They say, “We believe that the technologies we identify have potential to affect billions of consumers, hundreds of millions of workers, and trillions of dollars of economic activity across industries.” The age of depending on the ability to raise prices and use more leverage is gone for companies and without that benefit everyone is forced to reduce costs and run more efficient households, businesses and countries. Shifting from investment in a world of growth to progress means looking for those able to adapt.

“Stan is better at changing his mind than anybody I’ve ever seen. Maybe he stayed with it a little too long, but one of the great things about Stan is that he can and does turn on a dime. To paraphrase John Maynard Keynes, when the facts change, he changes his positions.”

-JACK SCHWAGER on Stan Druckenmiller in The New Market Wizards

Adapting to a world of low growth and rapid progress requires being flexible. This passage from The New Market Wizards is important in taking this thought of unlearning to another level. To be able to unlearn you have to be flexible and humble enough to have the strength to admit that you were wrong and nimble enough to make that decision quickly. The problem with using a model to determine whether to buy or sell something is that it reinforces the desire to wait or be stubborn. Unlearning starts with a belief that other than 1+1=2 there are no certainties, particularly when it comes to investing. Assets and economics are driven by people. People are not predictable and that is the reason why people like Daniel Kahneman have become so popular in recent years. The growth in popularity of behavioral finance is a reflection of the realization that emotion and psychology impact the way investors make decisions. Right now when I hear the “this is going to end badly” sirens going off, I try to ignore it and remember this great scene in The Big Short where Mark Baum and team are talking to a couple of mortgage brokers about the bad loans they were making.

Baum: I don’t get it. Why are they confessing?

Moses: They’re not confessing.

Collins: They’re bragging.

I cannot find people bragging about their investments in the markets today. It was evident in 2007 and it was certainly evident in 2000. I saw it in Brazil in 1997 and Mexico in 1994. I remember it related to commodities with my first trip to China in May 2008. Those situations did end badly. It doesn’t feel that way now. Sentiment can be very subjective, but if you read the news, listen to macro thinkers and consultants, look at returns and broad positioning surveys, listen to asset allocators and look at the political situation in this Presidential election, it is very difficult to describe people as bragging or bullish. For the first time in my career, I’ve noticed that even the sell side is writing that investors are saying the reason they are bullish is because everyone is bearish with this being a reason to say sentiment is now bullish so time to be bearish. Sentiment, to me, is surly for active managers and confused for asset allocators. As long as this is the case, I think markets will have an underlying bid to them driven by the real money needs and pressures.

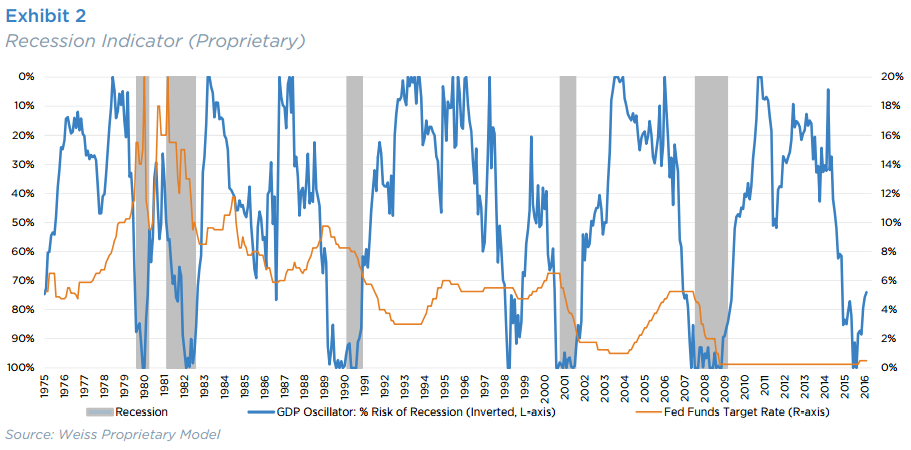

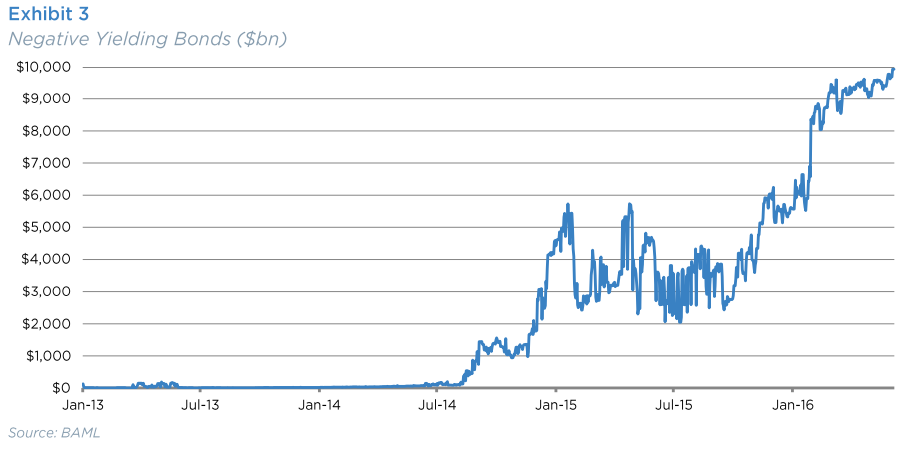

Whether people like it or not, if you go back to the reality of 3 month bills at 25 bps, each day stocks don’t come back to the “fundamentally” acceptable Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings ratio (“CAPE”) consultants are talking about, the pressure to invest rises. We have trillions of dollars of negative yielding bonds around the world and case that needs a home. At the same time, liability driven investors have a number to reach and like the debt clock in Times Square, it does not stop ticking. It may not make sense to people from a historical math perspective as to why anyone would buy a 30 year bond yielding 2.5% or stocks at a “high” multiple with low earnings growth, but the motivations for investing has a lot more behind it than just math. Not all countries have the same structure of liability driven investors (LDI), but those investors are global and valuations are relative so the developed world LDI problem will impact all assets over time. The clear risk, of course, is if rates move decidedly higher across the globe. It is incredible to listen to the fear in the market of whether the Fed Funds is 25, 50, or 75 bps given the need for these investors to meet a bogey much higher. Remember, 6.5% average before 2008. Due to the belief that in the coming years there will be more exponential progress in robotics, 3D printing, virtual reality, autonomous driving, next gen genomics, the Internet of Things, Al energy storage, etc., it is very hard for me to see a significant rise in rates coming, but that would be a real risk. Like last year when my articles were focused on the risk that our proprietary recession model (Exhibit 2) was highlighting while investor sentiment was not focusing on the benefits of lower oil for consumers, there will still be falls in the market. However, given the combination of the bounce in the model suggesting the recession is over, market fear and massive growth in negative yielding bonds (Exhibit 3) since our recession model first hit the risk level, I think for now risk assets are likely to remain strong.

“You must unlearn what you have learned.”

-YODA

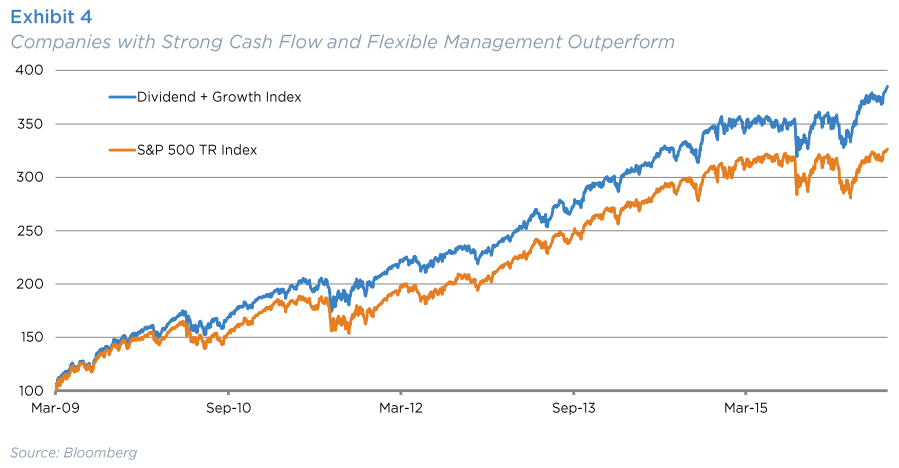

In thinking about investing with progress as a backdrop I think efficiency translates into multiple expansions for stocks, However, this is not about all stocks just going up. I do think a world of older established incumbents with strong cash flows and flexible management will continue to find ways to harvest more returns from the waste and benefit from low corporate borrowing rates. At the same time, we expect to continue to see the Amazon-like flexible companies with less physical and corporate structure constraints trade at high multiples. Exhibit 4 shows what a portfolio of 75% dividend stocks (Dow Jones US Select Dividend Index) and 25% flexible growth stocks (NASDAQ Index) has done relative to the total return of SPX since the crisis: Higher returns with a better Sharpe ratio and more contained drawdowns.

Outside of cash flow rich companies and flexible growth companies taking advantage of the innovation, as I have mentioned in prior articles, I do not think the most important evolvement that is likely to remain a story in the coming years is related to commodities. There is still a surprising number of people that think the regular supply and demand dynamics in the commodity markets still exist. It is surprising because the technologies that appear to be coming in the next five years have the potential to have far more impact on eliminating waste and moving to a more virtual world than we have seen since the smartphone. For this, I highly recommend reading the McKinsey piece mentioned above. This is extreme linear thinking and it has to be unlearned. Why should the price of a commodity be based on this year’s supply demand dynamic? If the new Saudi Arabian 31 year old millennial Deputy Crown Prince believes in the impact technology will have on demand over the next five years and wants to diversify his economy away from oil, wouldn’t the price reflect that outlook sooner? Rapidly declining solar prices, intense competition to find a battery storage solution, autonomous driving, virtual reality replacing unnecessary business travel, sensor based smart homes and commercial buildings, less building of physical commodities going higher. However, through investment strategies like risk parity or direct investing in commodities as an uncorrelated hedge, many are positioned in a way which synthetically are short progress. The argument is similar to the stock valuation side. If we look back at the last 75 years of data, I believe there should be enough data to be representative of what the next 10 years will look like. Although this may be true, I would not rely solely on short term supply/demand dynamics without spending some time on the timeline of upcoming innovations and their impact. I would again focus on being long efficiency and short waste. Commodities, to me, are waste and will remain in the secular decline albeit a slower one than what we’ve seen since 2014.

“The curious thing is that with these exponential changes, so much of what we currently know is just getting to be wrong. So many of our assumptions are getting to be wrong. And so, as we move forward, not only is it going to be a question of learning it is also going to be a question of unlearning.”

-JOHN SEELY BROWN

I’ll finish this article with a thought on the market. I continue to believe the largest winner in the years to come of progress are emerging markets. They have suffered in the transition from a world based around growth to progress. Their countries are currently built to be producers for the growth. Their leadership structures prevented the change, like Kraft. However, they are being forced by their own people to focus on the necessary structural reform. Dictatorships are crumbling. Organized protests are happening and their voices are developing clear messages. The light of information and transparency for the people has been turned on. It is not yet where it needs to be, but the progress is happening at a very fast pace. It helps that they have less to unlearn. If we based our opinion of the U.S., economically and dynamically, on what happened over the prior decade in Detroit or Cleveland, it would not be fair. In emerging markets there are lots of Detroits and Clevelands, where GDP focused regions need to change, but there the change there can happen far more rapidly. If we are at the elbow of technological innovation, you want to focus not on where these countries are today, but where they will be in five years. Markets discount the future, not the past. In a linear world, there is not much difference between today and two years out, but in rapid change you will see examples like you saw in the oil market over the last couple of years. The driving factor for why to expect to see the change now is the turning on of the smartphone. Smartphones are dumb without the Internet or enough wireless broadband speed. Only recently have emerging markets had the opportunity to fully use the power of the smartphone. The crisis of the last couple years brings the need for governments to speed up reforms and that is happening. Throw in the increase in negative yielding bonds across the world and the acknowledgement in February by both the PBOC and the Fed that they need to be aware of the impact their monetary policy decisions are having on the rest of the world and emerging markets look poised for change. The poster child of change from GDP to progress and efficiency in emerging markets and how quickly it can happen is China. The city of Shenzhen has gone through an amazing transformation to change from manufacturing giant to what is now called China’s Silicon Valley with giant tech companies like Tencent and Huawei. It is also home to global leaders in drones, cancer research and virtual reality. After a recent trip to Shenzhen, Time Magazine put out an article titled, “Why China is the Key to the Future of Virtual Reality.” We tend to ignore that on the Crunchbase Unicorn list of the largest private companies, 4 of the top 7 are from China and 9 of the top 19 are from emerging markets. Even if you do not agree that the time is right for China or emerging markets due to the debt issues, I think it is worthwhile to read the McKinsey reports from 2013 on emerging markets. These are two quotes from those reports.

“By 2025, almost half of the world’s biggest companies will probably be based in emerging markets, profoundly altering global competitive dynamics.”

“The Industrial Revolution is widely recognized as one of the most important events in economic history. Yet by many measures, the significance of that transformation pales in comparison with the defining megatrend of our age: the advent of a new consuming class in emerging countries long relegated to the periphery of the global economy.”

Over the last three years as I’ve been focused on progress, there was one problem that continued to haunt me. It was the distribution of wealth issue and the heightened anger with respect to the issue. This is another place where unlearning is an advantage. In a world of extreme competition with low barriers to entry, where prices continue to move lower, the arbitrageurs suffer and the lean, hungry ones with the least to unlearn will benefit the most. Go back and read the Daniel Pink excerpt again and think about what happens to the distribution of wealth problem.

Hopefully this paper provides some food for thought and can add to your brainstorming process. Even if progress is leading to better things in the future, there will continue to be risks and shocks along the way because any transition has its ups and downs. If anyone cares to talk further about any of these thoughts, do not hesitate to contact me. I want to unlearn as much as possible these days so I can learn.

Wrapping up, I’d like to share a recent experience that happens to fit this progress and emerging market theme. I recently met a very smart person who has been investing in Africa. He asked what I knew about Rwanda. I said not much, but what was in my head as he asked the question I am sure is similar to what most of you are thinking now. In my mind, I thought about the genocide, the movie Hotel Rwanda and the Tutsi refugees and the Hutu. Instead, he talked to me about the impact technology is having, how motivated and hungry the people are and the fact that Rwanda is the only country in the world where women hold a majority in parliament. I initially began traveling to China to unlearn what I was taught about China. I guess I need to travel to Rwanda next to unlearn.

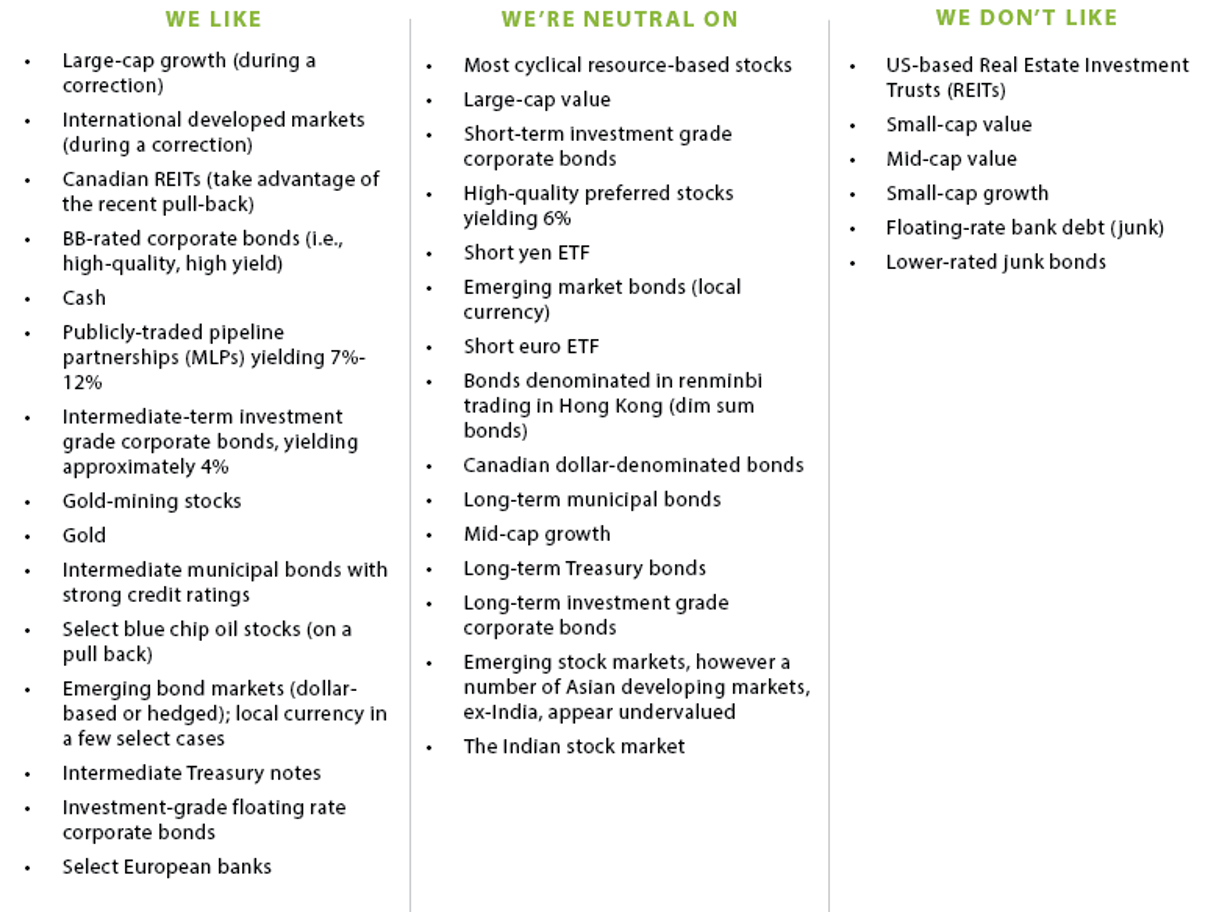

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.