“Would we be in the same mess today if Lehman Brothers had been Lehman Sisters?”

-New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof, in an article during the financial crisis.

The price of bias. This month’s edition of the Evergreen Exchange will reflect the differing viewpoints of multiple members from our investment committee. In the spirit of competition, we’ve begun to perform a survey to identify which author readers feel makes the most persuasive case. This week, we’ll tackle a topic that is largely overlooked by the investment world: behavioral finance. (Loyal readers will recall that this field of study plays an integral role in Evergreen’s approach to managing our clients’ assets.) Each author will discuss a behavioral bias that affects investors’ psyche and try to convince readers that their choice is the greatest threat to portfolio returns. Specifically, I will address the recency effect, Jeff Eulberg will cover loss aversion, and lastly, David Hay will explore overconfidence.

To attempt to make the most compelling case for this edition, I focused on the essence of the question we are tasked with answering: What bias is the most hazardous to future portfolio returns? If I am to answer this properly, I have to understand what type of behavior destroys good returns. It seems straightforward that buying at high prices and selling at low prices is the greatest error any investor can make and, unfortunately, it happens all too often. It’s common because we all suffer from the recency effect, a subcategory of the serial position effect. While those may sound like terms that would be covered in a forensics course, I assure you the concept is both simple to understand and critical for good decision-making.

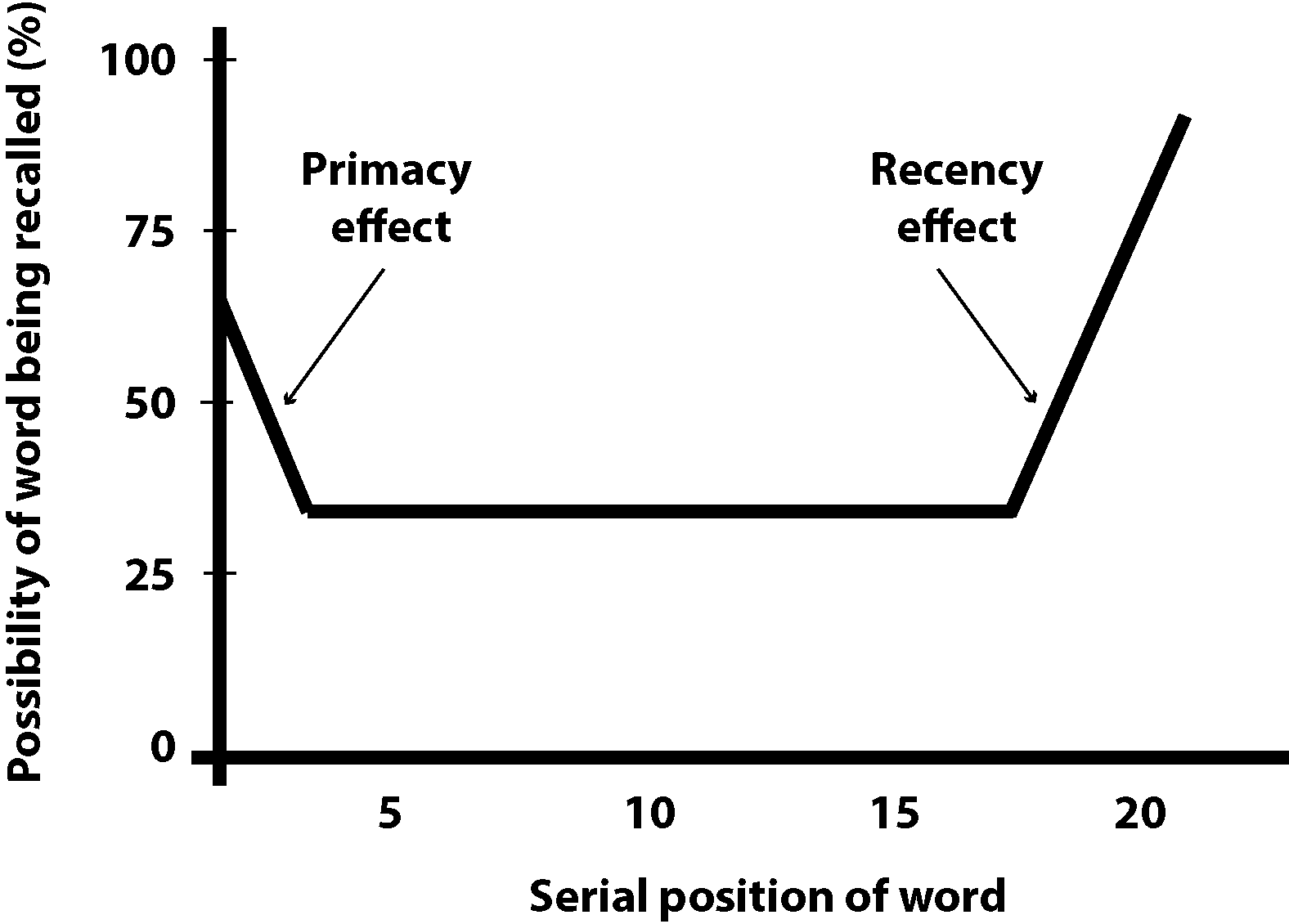

The serial position effect is extremely basic and intuitive. It says people find it easier to recall something that occurs early (primacy effect), they struggle to remember events in the middle, and they best recall what happens to them last (recency effect).

NOT-SO-TOTAL RECALL Source: University of Washington

Source: University of Washington

But why is this? Well for starters, it’s easy. Whether you prefer the word efficient or lazy, it takes less mental energy to recall recent events. Marketers use this all the time in advertising in hopes of leaving consumers with a vivid memory. One powerful concept of the recency effect is how automatically it occurs. It’s our default way of thinking. If I ask you to recite your favorite hotel or bottle of cabernet, most of us, without conscious intent, begin the process of answering by recalling a recent experience. (For readers interested in a deeper look into the conscious and subconscious thought process, Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman wrote a terrific book that explores this in fascinating detail called Thinking Fast and Slow.)

When it comes to investing, the implications of the recency bias are obvious. If investors place too much weight on recent events, they tend to make decisions that extrapolate the current environment too far into the future. We certainly saw this mistake firsthand during the financial crisis. In fact, when the markets plummeted by 5% on a single day in 2008, a client called to tell me that if they lost 5% for 19 more days they’d be broke. Regrettably, I glibly replied that if the markets go to zero the problems facing everyone would be far beyond simply financial ones. (I don’t remember if that helped the client calm down or infuriated them!) It’s critical to understand that projecting what’s happened recently into the future is deeply ingrained into in the human psyche. Even worse, that seems to be most prevalent when markets are in extreme conditions.

Today’s environment is a perfect case study. If you ask investors their favorite asset class, they would likely say stocks. In 2009, it was quite the opposite. As a result, the recency effect makes it very hard for humans to follow Buffett’s advice of being fearful when others are greedy and greedy when they are fearful. Projecting recent events into the future may not be a conscious attempt to be greedy or fearful, but it’s absolutely devastating to managing money.

Cognitive biases aren’t something that some have and others don’t. We all have them—some more than others. Don’t despair; there are two pieces of good news for investors. First, it’s possible for investors to setup guidelines or rules, to minimize cognitive biases that can impair financial prosperity. Second, these biases create market inefficiencies, which is really another word for opportunity. At Evergreen, we have developed an investment strategy that has allowed us to identify when markets fall under these cognitive spells. I’m partial to it because it’s not a bet on how well we can forecast or make sense of markets. Instead it operates under the assumption that people are human and that we can’t perfectly balance our emotions with rational thought. There are many out there who think that markets are efficient because people are rational. Have they watched the evening news lately?

Our job as investment managers is part financial expert and part psychologist. And when markets are at extremes, low or high, it can lead to some difficult discussions with clients. I often think the best way to protect clients from the recency effect is to invoke the words of medieval Persian poets, often mistakenly attributed to President Abraham Lincoln: “This too shall pass.”

Being fearful when others are fearful. For most of my teenage years, the game of football was my primary focus. Now, don’t get me wrong, my mom made sure I still earned good grades, but when I wasn’t studying, I was doing something football-related. Today, with a young family, priorities have certainly changed. While the game is no longer my only focus, it’s still often involved in a good amount of my limited free time.

Every summer, a group of my very close friends get-together and, although we call it a golf weekend, it’s really just a way to celebrate the start of football season. At the end of the football season, we all get back together and enjoy the Super Bowl in Las Vegas as a grand farewell. The last two years, with my beloved Seahawks in the Super Bowl, I found myself making emotionally-driven wagers on the outcome.

In 2014, even though I wasn’t convinced that the Seahawk defense could slow down the legendary Denver Bronco offense, I had to place a small “punt” on my favorite team. Fortunately, my uncertainty was misplaced; I won my bet and had a successful Vegas weekend. This year, when the Seahawks made it back to the Super Bowl, I was convinced we were the better team. So, I took half my winnings from the year before and again bet on the Seahawks. The Hawks ended up a yard short, as we all know, and I lost my wager.

In spite of my confidence in the team, I only bet half of my winnings from the year before. In this case, my desire to avoid losing money, and preference to keep what I had already won, helped me avoid making a bigger mistake. Loss aversion is the human tendency to go to greater lengths to avoid losses than to reach for potential gains. As any Seahawks fan can attest to, we are wired to feel losses more deeply than victories. Studies have actually shown that loses are twice as powerful, psychologically, as gains. In the example above, this tendency actually helped me. However, this behavioral investing flaw has led many investors to miss market opportunities and is a key reason market crashes happen so suddenly.

In 2008, when the market was plummeting, many of the prospective clients I met with wanted out. I remember attempting to explain why valuations were attractive, and how, in the long run, that was actually the time to buy. I often heard the rebuttal, “I don’t care, I can’t handle seeing my account go any lower.”

Loss aversion was first proposed as an explanation for another behavioral investing flaw called the endowment effect. The endowment effect is the human tendency to place a higher value on something that we own, even if there is no reason for attachment. Essentially, we are wired to believe that our investments are worth more than the markets price them at. Further, when markets sell off, we often believe that they are mispricing our prized assets and the losses will eventually be recovered. Thus, the fear of losing keeps us from recognizing an error in judgment until our primal survival instinct forces us to abandon ship and avoid further losses.

Humans tend to do this even when our rational brain tells us we are making a costly error. Basically, our irrational fears overwhelm our rational thinking. We believe this is a key reason markets go down faster than they go up. Fear is a more dominant emotion than greed.

For now, the painful memories of 2008 have dissipated, and clients feel like I did heading to Vegas with gains from the previous year in my pocket and willing to reach a bit more. Most investors I meet with today have accounts above their 2007 peaks. Due to these perceived gains, and in spite of significantly stretched valuations, investor’s are willing to take on more risk. (This is where another costly bias that Dave is writing about—overconfidence—begins to kick in. In a way, being excessively confident during good times is the opposite side of the same coin of acting with extreme loss aversion in a market panic.)

The trouble happens when losses start to occur. When investors are positioned more aggressively, they eventually experience painful and rapid losses, and often fully liquidate after reaching their maximum tolerance for losses. For others, the endowment effect will kick in, and they’ll believe the market is mispricing assets and it’s only a matter of time before the recovery happens. Some investors will hang on for the ride; others will liquidate at the worst possible time. Usually, the more volatile the asset mix, the more inclined the investor is to bail.

At Evergreen, we have systems and processes in place to avoid these common mistakes, or at least minimize their impact. We have sell disciplines to help us from falling victim to the endowment effect, our investment decisions are thoroughly researched by our investment committee, and we believe deeply in paying a reasonable valuation for every investment. Due to this belief, and because markets over-shoot in both directions, we will rarely call the top or bottom of a market. We will keep our clients appropriately invested by understanding their individual risk tolerance and maintaining appropriate asset allocations.

Today, the once shocking losses of the great financial crisis are barely visible in many investors’ rear view mirror. But once accounts start to decline, the same old self-preservation instincts will reassert themselves. Many investors will wish they didn’t reach for those late-stage bull market gains, as the losses they incur will be too much for them to stomach. At that time, when valuations present better odds for greater long-term returns, and excessive loss-aversion has replaced overconfidence, we will be buyers. We don’t expect to have much company.

Before the Fall. To err is truly human, and I believe it’s fair to say that our biggest face-plants happen when we become too full of ourselves. Perhaps nowhere is this more true than in the financial markets where hubris might be the most deadly sin. Consequently, I’m focusing my section of the Evergreen Exchange on the behavioral investment flaw (also known as a cognitive bias) of overconfidence.

It may seem like stating the obvious to say that cockiness becomes particularly prevalent late in a bull market (such as after six years of mostly steady appreciation, like now). But, in every up-cycle, it seems as though markets indulge in a case of mass amnesia. Years of making money cause memories of excruciating losses to fade. As a result, investors become more risk-tolerant and, ultimately, overconfident.

To anyone who has gone through a few full market cycles, this is far from an “Aha!” moment. But according to the orthodoxy of the Efficient Market Theory (EMT), it is a false observation. After all, based on EMT, emotions don’t influence investors. Right!! Actually, that precept has become so preposterous with the passage of time that the EMT apologists have tweaked it along these lines: To the extent emotions influence investor behavior, they tend to off-set. In other words, if a subset of market participants become too greedy—or too confident—and drive prices up excessively, an approximately equivalent cohort will become fearful of the inflated values and sell to bring them back in line.

It’s a nice twist on the basic theory and, most of the time, that’s probably what happens. Markets stay in a kind of rough equilibrium between buyers and sellers. But then there are those odd events that really drive EMT believers bonkers: bubbles. These aren’t supposed to happen in efficient markets, yet even a casual observer would realize these have occurred relatively frequently in various asset classes over the last two decades. There certainly could be multiple causes for the increased occurrence of speculative manias, including the Fed’s over-easy (they are a bunch of eggheads) monetary policies. However, it’s my contention that overconfidence has played a starring role. And one of the reasons for that might be gender. Come again?

The money management industry continues to be a bastion of male domination. Certainly, women have made substantial in-roads in recent decades, just as they have in Corporate America overall. But, the reality is there are a limited number of high-profile investors who belong to the fairer sex. This is unfortunate for several reasons, but relevant to my topic at hand, it’s because they are actually better suited to the job. My logic—with several recent and not-so-recent studies to back me up—is that women are less susceptible to falling prey to hubris.

Whether it’s genetic or a socially acquired trait is beside the point. Women don’t exhibit nearly the degree of arrogance when it comes to investing as do men. Overconfident investors are overactive investors. Over-trading is a well-documented path to investment underperformance, and men are much more willing to go down it, causing their returns to suffer relative to female investors. According to a study of 35,000 discount broker clients conducted in the late 1990s, men trade their brokerage accounts 45% more often than women, costing them nearly 1% a year of comparative return from this bad habit alone.

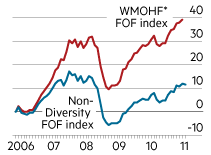

DIVERSE HEDGE FUNDS RULE CUMULATIVE RETURNS (%)

Source: Barclays Capital; *women and minority-owned hedge funds

Interestingly, this isn’t just the case among amateur investors. Hedge funds, which are supposedly (emphasis on supposedly) managed by the shrewdest investment pros extant, reveal much the same phenomenon. Per The Financial Times’ John Authers, quoting a Barclays study, in the five years through March 2011, funds run by women and/or minorities dramatically outperformed those run by men. (It’s my suspicion women are also much more judicious in their use of leverage; excessive debt has brought down many a hedge fund.)

Notice that this study also includes minorities. This reveals another element that leads to overconfidence, namely, homogeneity, or said inversely, lack of diversity. If you’ve ever been to a Wall Street trading floor, you’ve seen they’re largely comprised of young white males. (The average age is 30 and about 30% started within the last five years, meaning around one-third have never endured a bear market!).

Many have attended the same schools and have been indoctrinated with the same theories—including oodles of EMT. In fact, that’s often how they’ve gotten hired—knowing an alum of say, Wharton, who works for Goldman. Often times, they were part of, as Howard Cosell was known to disparagingly refer to it, the “jockacracy.” In other words, they excelled at football, hockey, or basketball at their schools.

Certainly, there’s nothing wrong with being a former athlete at a prestigious university and leveraging that into a Wall Street career. But it does produce a dangerous tendency toward homogeneity, and, similarly, group-think. And if you’ve always been a success in academics and sports, you generally are pretty confident in your abilities and those of people similar to you.

Accordingly, there is a strong desire to keep up with one’s peers and to assume they know what they are doing. The thought process goes something like this: “If my frat brother, Joe, is buying small-cap stocks, they must be good. Besides, he’s been crushing it lately. He’s got a hot hand now just like he used to get on the basketball court. I can earn a bigger bonus if I get in on that.” Thus, it’s not merely overconfidence in one’s own ability, but also in those who are part of your “tribe.”

Here’s a quote from one of the studies that I read on this dynamic that rang true to me: “In a modern market, where competition is key, undue confidence in others’ decisions is counterproductive. It can discourage scrutiny and encourage imitation of others’ decisions, ultimately causing bubbles…Moreover, empirical evidence shows that people surrounded by ethnic peers tend to process information more superficially.”

And one more: “Such superficial information processing can engender conformity, herding, and price bubbles. As the term implies, herding is not the outcome of careful analysis but of observational imitation.”*

Therefore, perhaps the reason women are so important in money management is the diversity they bring to the investment process—male money managers are from Mars and female money managers are from Venus. As the study notes, diversity creates friction and anyone who has ever been married knows about male/female friction!

Various studies have shown that women are far more humble and risk-averse than men. It’s my belief they are also less inclined to trade like their peers than are men. They are clearly not predisposed toward “macho investing”, reducing the odds they will pile into an overly-popular and over-valued investment theme or sector. According to a State Street research paper, 69% of investors in 16 different countries (predominantly men) exhibited pervasive overconfidence. Men also had the unattractive tendency to take credit for their investment triumphs and blame others for their flame-outs. Women tend to do the opposite—ergo, less ego, less hubris, better results.

It’s fair to note that the investment world has always been male-dominated, and yet, bubbles were relatively rare prior to the late 1990s. To reiterate, I have little doubt the mostly incontinent Fed policies since then deserve much of the blame. But technology, and the instantaneous connectivity that it has brought, is likely a major factor as well. All of those male hormones and well-honed competitive instincts, linked together in nano-seconds, plausibly rendered market conditions much more combustible.

Yet, most of the greatest investors of all-time were men. Obviously, they were able to overcome their own overconfidence. For years, Warren Buffett never even had a quote machine on his desk. He intentionally chose to remain in Omaha to be far removed from the thundering—and often blundering—Wall Street herd. Similarly, John Templeton worked from his enclave in the Bahamas.

Considering that Evergreen’s investment team is mostly white males, several of whom are ex-star athletes (that second category excludes yours truly!), we are certainly not above succumbing to overestimating our abilities or following our peers into crowded trades. But, as believers in behavioral finance, not the efficient market theory, we work very hard to resist the siren song of imitating others, particularly when they’ve been on a hot streak. We are who we are: contrarians. This often means we are prepared to look stupid in the short-term to look smart in the long run.

Believe me, being a contrarian you learn a lot more about humility than hubris. Who knows? Investing as a contrarian might mean becoming more in touch with your feminine side. I’m okay with that. Perhaps a lot more male investors should be, too.

Clarification: Last week’s EVA alluded to a leading oil service and transport entity that has a $600 million asset entering service later this month. The actual total value, including assumed debt, is roughly $1.25 billion. (For those who track the MLP space closely, this ship is technically known as a FPSO—a Floating Production Storage and Offloading vessel.)