Not-so-safe assumptions. One of those simple but clever old sayings goes, “You know what happens when you assume: You make an ass out of you and me.” Despite that admonition, we all continually make assumptions every day. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in the oft-intersecting worlds of investments and economics.

For example, there are certain bed-rock assumptions about finance that are too obvious to question, such as lenders will always receive a positive rate of return on the funds they extend (at least from a safe borrower who doesn’t default.) In a healthy economy, this means an actual real yield (i.e., net of inflation).

It’s also assumed that during times of easy money—and none could be easier than right now—lending longer term would yield much more than lending short. For those EVA readers with a bit of economic theory in their backgrounds, you would recognize this as the steep yield curve scenario, where short rates are considerably lower than long rates. This is a classic situation when central banks are seeking to stimulate the economy by driving short rates down. The inverse is the dreaded inverted yield curve when short rates are higher than long rates, a condition that almost always precipitates a recession.

Yet, as investors are slowly and uncomfortably accepting, this fundamental belief about the return on lent capital is being increasingly disabused (and those with money to lend are also feeling a growing sense of being badly abused). Even stranger, it’s become ever more common to accept a negative return on money placed with a purportedly safe borrower, even before inflation is considered.

Lenders to governments in Europe are particularly getting the short end of the deal—even when they invest long. Yields on government debt in Switzerland are negative out to 10 years, in Germany out as far as seven years. Meanwhile, Sweden and Denmark are seeing negative yields on even shorter maturities. In numerous other countries around the globe, yields seem to be heading that way with sub-1% 10-year bond yields for even less-than-stellar credits like France, and barely over 1% for countries that not long ago were in the pariah category, such as Spain and Italy. Of course, there is also debt-drenched Japan where rates are essentially zero all the way out to 10 years. Japan was long believed to be a special oddity but now we are finding it was, in actuality, merely ahead of its time.

It’s true that if there is an expectation of deflation, as has been so often the case in Japan, a zero interest rate might be a good deal. However, that brings up another basic assumption that is under siege these days: Fabricating vast sums of money was supposed to render falling prices a virtual impossibility. Instead, endless experiments in quantitative easing (QE) have made it a virtual reality in some countries, one that is more real than virtual—and certainly not virtuous.

Even those nations not enduring deflation are flirting with it. A prime case in point is China, which not long ago was dealing with the high inflation that hyper-growth often brings. Lately, inflation in that land of the 1.4 billion mouths to feed (not to mention several hundred million palms to grease) has tumbled down to the eurosclerosis-like level of 1%.

Truth be told, many of the assumptions that prevailed when central banks first discovered the “thrills of trills” (i.e., printing money by the trillions), have turned out to be as inaccurate as the Club of Rome’s infamous 1970s assertion the world would run out of oil by 2000.

The lengthy list of assumptions-gone-awry includes the one that seemed to be a lead—not to mention zinc, copper, and steel—pipe cinch.

A most unlikely victim. Few would have suspected that when the Fed launched QE1, as it valiantly and desperately sought to avoid the second coming of the Great Depression, it was opening the floodgates to over $10 trillion of global QEs. Even fewer would have believed that if such an unlikely chain of events were to transpire, it would sound the death-knell for the so-called “Commodity Super-Cycle”.

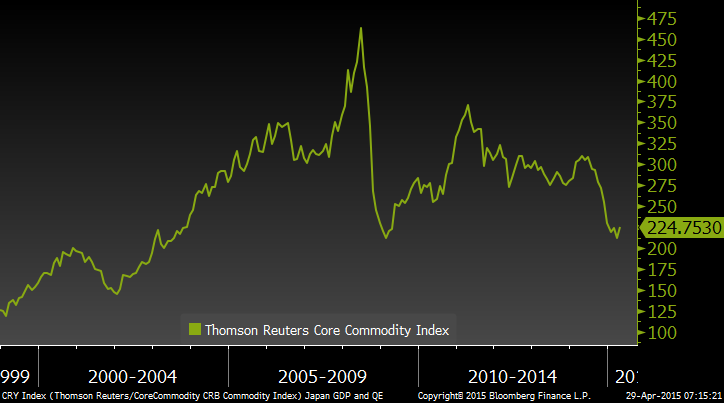

This referred to the epic rise in the price of “real” resources such as metals and energy. The commodity lift-off began around the time the Greenspan-led Fed allowed short-term interest rates to fall (and stay) far below the economy’s growth rate in the early 2000s. As you can see, this cycle was super indeed—at least until 2008—and, undoubtedly, it was heavily influenced by China’s consumption of around 40% of almost every resource known to man.

FIGURE 1: THOMSON REUTERS CORE COMMODITY INDEX Source: Evergreen GaveKal, Bloomberg

Source: Evergreen GaveKal, Bloomberg

After commodities were massacred during the Great Recession, they managed to stage a spirited rally into 2011. At the time, as you may recall, the silver ETF was trading more heavily than the S&P 500 version (the SPY) and you could barely have your TV on for a few minutes without seeing an ad about buying gold.

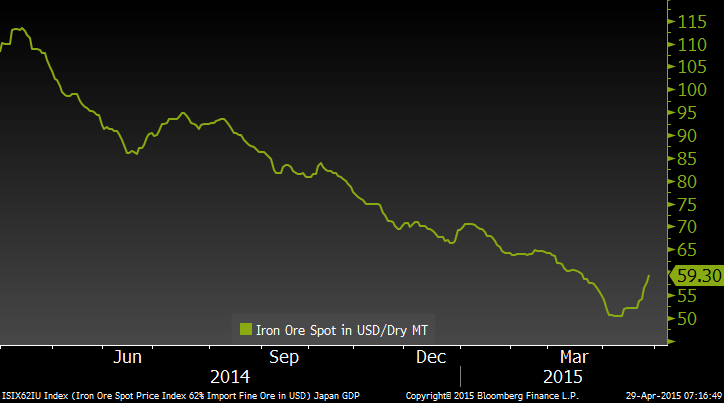

This seemed logical enough given the assumption that massive money printing simply had to drive up finite resources like precious metals—and even not-so-precious metals such as iron ore. But, over the past year, that essential steel-making ingredient has been melted down to a mere ingot of what it once was. While the S&P/Goldman Sachs Commodity Index has held up better, it is still down 34% over the last 12 months, tumbling to the lowest level since 2009 (when the planet was still in the throes of the global financial crisis). In the process, almost all industrial metals having been taken to the wood shed (or should that be metal shed?)

FIGURE 2: IRON ORE SPOT PRICE (USD/DRY MT) Source: Evergreen GaveKal, Bloomberg

Source: Evergreen GaveKal, Bloomberg

Although not many of us care much about the price of iron ore—or even gold and silver these days—another commodity is a far different story. Oil is top of mind for almost everyone, particularly when we head to Costco to “fill ‘er up”. After trading in a narrow range around $100 for years, crude has been cracked like so many other run-of-the mill commodities, plunging over 60% from peak to trough. This is certainly great news for consumers worldwide but, once again, such an outcome would have seemed impossible during an era of central bankers gone wild. (Perhaps this staid collection of eggheads is making up for missing all the fun during the spring breaks of old when their classmates indulged in sex, drugs, and rock and roll).

As the Wall Street Journal observed in a recent front page headline, the “World Is Awash In Too Much Of Almost Everything.” Oversupply does keep consumer prices down, but not everything about this glut is a good thing. Unquestionably, one item that the world is awash in is debt.

Another widespread assumption was that when the financial crisis ended, a deleveraging cycle would begin, lowering debt relative to the size of the global economy. Instead, in the world’s three most important economies, government, business, and consumer debt has swelled. In the US, it has risen from 167% of GDP to 180%; in the eurozone, debt has expanded from 180% to 204%; in China, the increase has been much greater, from 134% to 241%. Overall, global debt is up a cool $57 trillion over the last eight years. These figures highlight why numerous past EVAs have asserted that what many pundits predicted would be The Great Deleveraging was, in truth, The Great Illusion.

Also, as pointed out in the WSJ article—and, once again, not a felicitous factoid—total US inventories of manufactured durable goods have lately risen to the highest level in nearly 25 years. Generally speaking, high inventories imply lower future production and output of long-lived items has already been chronically disappointing in this expansion.

This latter statistic is another reality that almost no one, especially the print-meisters, would have assumed when they began their grand experiment in monetary magic.

O productivity, where art thou? Central bankers are certainly not stupid people. In fact, they are among the planet’s most academically-accomplished individuals (the key word being “academically”). They knew they were taking a big risk with QE, but the assumption was there was no other option with most governments in a perpetual state of paralysis. Ergo, they felt compelled to test the theory that by flooding the world with money, they could lower interest rates, force asset prices up, and eventually trigger a healthy economic cycle. (Two out of three isn’t bad, but the last one does matter most.)

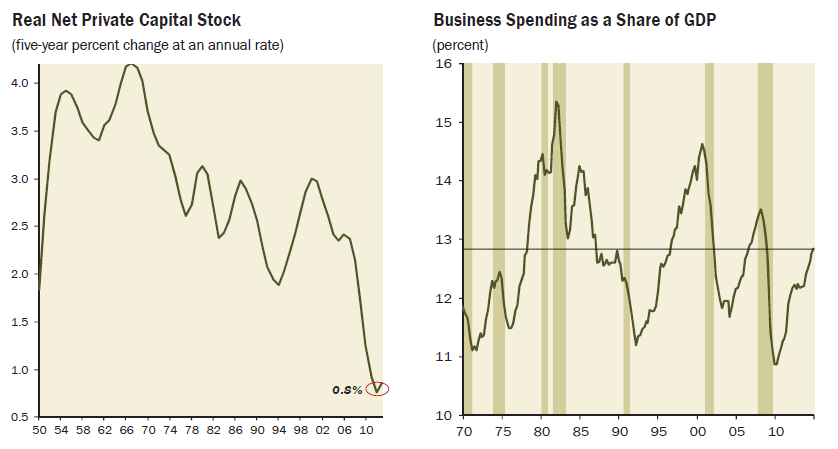

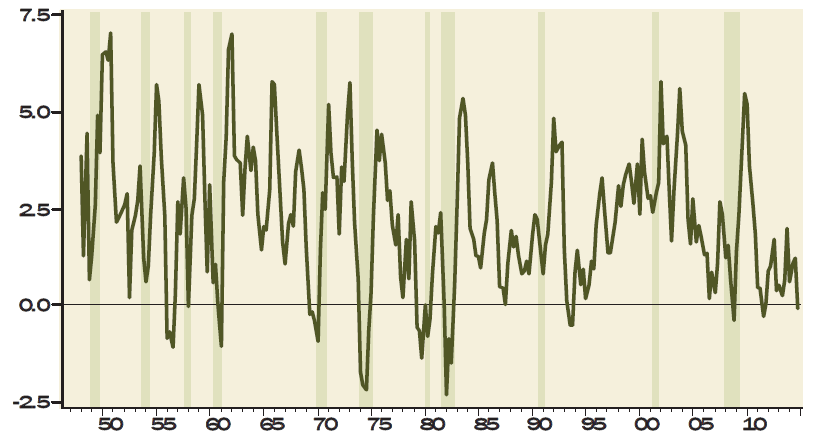

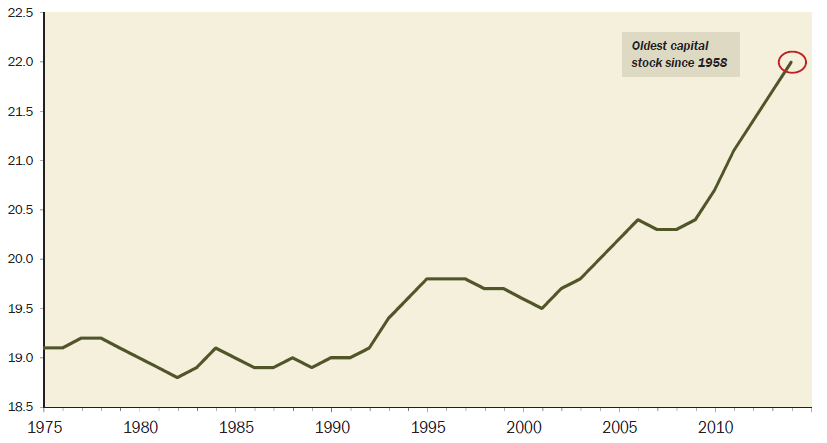

This sequence was also presumed to ultimately cause businesses to invest in those fixed assets that promote productivity (think: computers and new industrial machinery). Yet, as discussed in numerous past EVAs, that’s another assumption that has gone down in flames. Both capital spending and productivity are in long-term downtrends, with the former development rendering America’s capital stock ancient in the extreme.

FIGURE 3: WEAKEST GROWTH IN PRIVATE CAPITAL STOCK IN 60 YEARS Shaded regions represent periods of US recession

Shaded regions represent periods of US recession

Source: Federal Reserve Board, National Bureau of Economic Research, Gluskin Sheff

FIGURE 4: REAL OUTPUT PER HOUR OF ALL PERSONS (YEAR-OVER-YEAR CHANGE)

Shaded regions represent periods of US recession

Source: Haver Analytics, Gluskin Sheff

FIGURE 5: UNITED STATES, AVERAGE AGE OF PRIVATE FIXED ASSETS (IN YEARS)

Source: Haver Analytics, Gluskin Sheff

There may be multiple reasons for the relentless bear market in productivity but I do agree with the theory (OK, assumption) that a major factor is that it’s safer for a company to goose earnings through share buy-backs than via making long-term investments (which may or may not be rewarding). Investors have certainly celebrated this approach but it’s reasonable to question just how healthy it is for the sustainable growth of our nation’s economy. It’s hard to overstate the importance of productivity to sustaining economic vibrancy, though I’ve given it my best shot. In an aging society, which almost all the leading economies are these days, it’s the only way to achieve the kind of growth rates needed to extricate us from our debt traps.

The assumption has been for years that it was only a matter of time until companies, flush with cash and emboldened by low interest rates, would open their checkbooks on capital projects. Yet, the years go by and the “cap ex” numbers continue to erode. Without robust capital spending, it’s nigh on impossible to generate adequate productivity.

The only thing that might be more out-of-favor right now than commodities is the reputation of one of my favorite sources for cogent thinking: John Hussman. Many EVA readers know that John was once among the most radiant stars in the investment firmament, but has now been relegated to village-idiot status due to his poor performance over the last six years. However, I don’t know how anyone can read the following and not be moved to question the assumptions of those currently pulling the monetary levers:

“All securities are essentially a way to trade current saving for a claim on future output. The value of all the securities in the economy derives from the claim on future output that this stock of real and intellectual capital can generate over time. During speculative bubbles and periods of malinvestment (my note: like companies buying back their own stock at ever higher prices) saving is invested in unproductive projects that essentially result in unintended consumption (my note again: think massive write-offs due to overpaying for acquisitions). This means that the stock of outstanding securities is essentially ‘backed’ by a smaller stock of productive capital to service those securities over time. This point is fundamental, because it is a part of the reason the US economy has been failing much of its population. The economic policies we’ve pursued have put a premium on current consumption and have encouraged yield-seeking speculation, while discouraging saving and productive investment in both the private and public sectors.”

As former perma-bear, turned quasi-bull, David Rosenberg, wrote last month, “the private sector capital stock has eroded so much that productivity is not only slowing, but contracting outright.”

It could be argued that another reason companies are engaging in short-termism and not investing for the future is the aforementioned glut in so many real assets. Yet, that means there is insufficient demand and the assumption by those Jim Grant calls the “monetary mandarins” was that such a shortfall could be eliminated by whipping up enough ersatz money. Stoking demand has for sure worked with stocks and bonds (hence the reason investors are willing to settle for yields that are an insult to the word “pathetic”). But where’s the beef when it comes to the real economy?

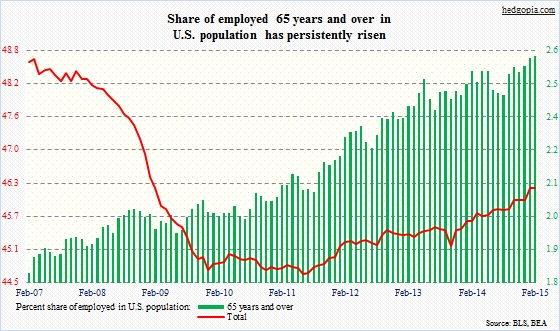

Yes, I realize the labor market looks healthy, with “looks” being the operative word. If it’s as good as it seems, though, how come there are over 100 million employable Americans not working? And why are 46 million US citizens using food stamps, up from less than 7 million in 2000 (before the Fed began its uber-easy money policies)? Why is the share of 65 year olds in the labor force continuing to rise?

FIGURE 6: SHARE OF EMPLOYED 65 YEARS AND OVER IN USPOPULATION HAS PERSISTENTLY RISEN Source: BLS, BEA, Hedgopia.com

Source: BLS, BEA, Hedgopia.com

Perhaps the pervasive belief that the central banks have carried the day--and the related attitude deriding those who are wary of the stock market—are both as ill-founded as so many other assumptions of recent years?

Bull market, you say? Those in the economic intelligentsia who have been promoting the war on interest rates, and other cheap money tactics, are feeling pretty full of themselves these days (I’ve heard several of them waxing victorious this week at the annual Altegris/Mauldin Strategic Investment Conference). Their proof positive is the soaring stock market. Some of them are prone to ridicule those who quibble with valuations and sustainability (in my case, guilty, as charged).

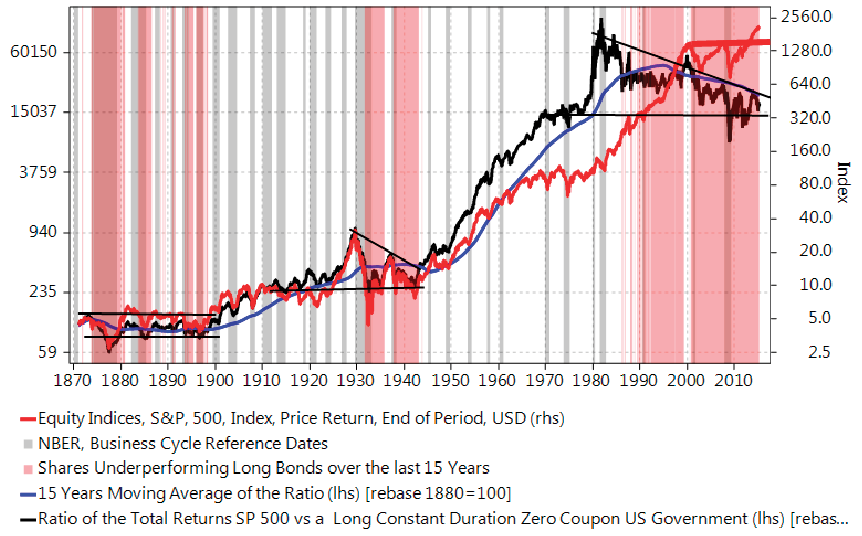

Incredibly, though, despite the S&P currently being among a handful of the most expensive markets ever witnessed, the return on US stocks has been just 4% annually this century/millennium. That’s 15 years of not much, and most foreign markets have done worse. Coupling that with the fact America’s GDP growth has run at about half of its multi-decade average in that same time period, a neutral observer might wonder why the bulls are feeling their oats.

While stocks have limped along since 2000, despite the rousing rally of the last six years, long-term treasury bonds have left them in the dust, roughly doubling the return on equities (that’s not the kind of ROE the bulls like to discuss). And, as the formidable Charles Gave has written, even if you go all the way back to 1980, at the dawn of the greatest bull market of all time, stocks have lagged long-dated zero coupon government bonds.

FIGURE 7: TOTAL RETURN US SHARES VS. US LONG DATED GOV. BOND BASE 100 IN 1880 Source: GaveKal Data/Macrobond

Source: GaveKal Data/Macrobond

This is certainly not to say bonds are a compelling investment currently. A few years ago, it was fashionable for many market mavens to bandy about the phrase “bond bubble”. Lately, that term has largely disappeared from the financial media, but if there was ever a time to bring it out, this is it. (However, there are some pockets of decent value in the US bond market, one of the last bastions of livable cash flow anywhere in the world).

For nearly all financial assets, the dominant assumption currently is that the central banks can prevent bear markets in stocks and bonds. In the Evergreen view, that mindset is precisely why we believe we are skating on thin ice during a spring thaw right now. With such a long list of assumptions gone awry over the last five years, such an extreme example of group-think should cause a rational investor’s skin to crawl. The financial wagers are so skewed in the direction of assuming (there’s that word again) limited downside that any negative shock will almost certainly cause massive reverberations.

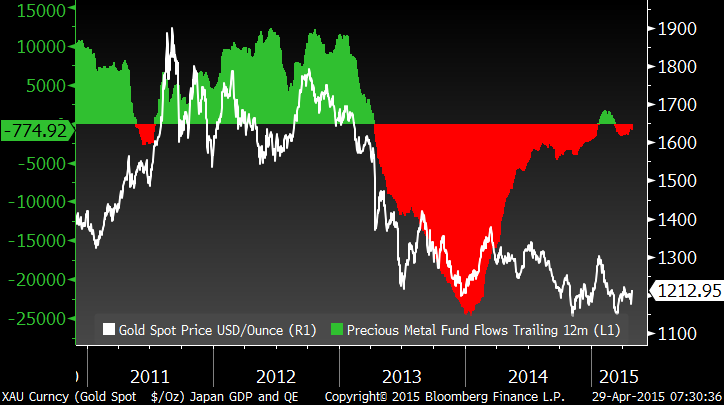

On the other hand, those areas, such as commodities—where the popular assumption now is that they are victims, not beneficiaries, of QEternities--appear much safer (as ironic as that it to say about commodities). We would suggest looking at those that have stabilized, like gold and silver, and where sentiment has once again soured. Encouragingly, outflows from gold-related funds and exchange traded products have been occurring for years, meaning trend-following investors are long gone.

FIGURE 8: GOLD SPOT PRICE (USD/OUNCE) AND PRECIOUS METAL ETF FUND FLOWS Source: Evergreen GaveKal, Bloomberg

Source: Evergreen GaveKal, Bloomberg

At some point, oil-related investments will be attractive as well, but the combination of their recent recovery and crude inventories being literally off the charts leaves us cautious for now. The fact that hedge funds have, of late, made major bullish wagers on oil also leads us to believe another shakeout looms.

FIGURE 9: US CRUDE OIL INVENTORIES

Avoiding participation in so-called “crowded trades” is essential in our view. Since all investors, including us, are in totally unfamiliar terrain, following in the hoof marks of the herd is a sure way to get trampled when it realizes it is heading in the wrong direction and suddenly reverses course.

As I close this EVA edition, I would be badly remiss if I didn’t admit that many of my assumptions of the last few years also didn’t turn as expected. For example, I never imagined that the Canadian dollar could fall back to its Great Recession low, relative to the greenback, given the much sounder fiscal and monetary policies north of the border. Similarly, I couldn’t envision in 2012 that gold, with so much fake money spanning the globe, was poised to enter a full-blown bear market, rather than just correct its overbought condition at the time. Nor did I believe investors would be so gullible as to once again pay high P/Es for top of the cycle S&P 500 earnings (which look to have peaked last year) when our country’s long-term growth rate has been essentially cut in half.

The fact of the matter is, as I’ve noted before, this is a world none us have ever seen before, particularly when it comes to the cost-free cost of capital. Since money is vital in the extreme, when it is as blatantly mispriced as it is today, it doesn’t require a daring assumption to realize a lot of things must be out-of-kilter. If you are assuming that’s not the case, you might be sticking your hind-end out much more than you realize.