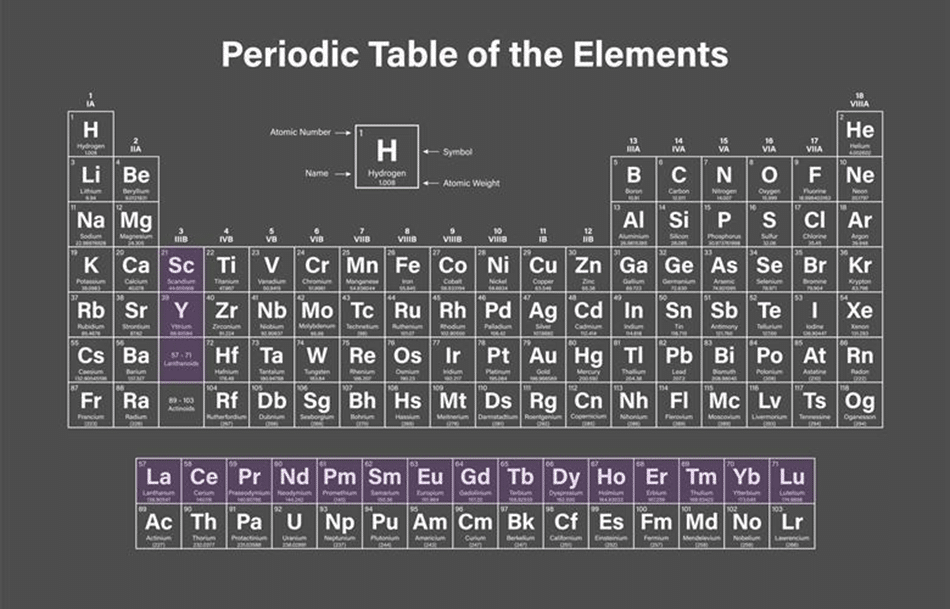

Rare earth elements (REEs) are the unsung heroes inside smartphones, electric vehicles, wind turbines, and modern defense systems. Though not actually “rare” in the Earth’s crust, these elements—shown in purple on the periodic table—are difficult to mine, separate, and refine in economically viable concentrations. While rare earth elements may not be household names, they are embedded in countless high-tech products that underpin daily life and modern economic growth.

As one U.S. government report notes, rare earth elements are integral to a wide range of commercial and national security applications, from smartphones and computers to electric vehicles, wind turbines, and missile guidance systems. As global demand for electrification, digitization, and advanced defense capabilities accelerates, so too does demand for rare earths.

Global Supply: Who Holds Reserves and Controls Production?

When it comes to rare earth supply, one country towers above the rest in both geological reserves and current production: China.

China controls approximately 44 million tonnes of rare earth reserves—nearly half of the global total—and has been the world’s dominant producer for decades. In 2024 alone, China mined roughly 270,000 tonnes, accounting for about 70% of global rare earth output. Just as important, China also hosts nearly all of the infrastructure required to process these minerals into usable materials.

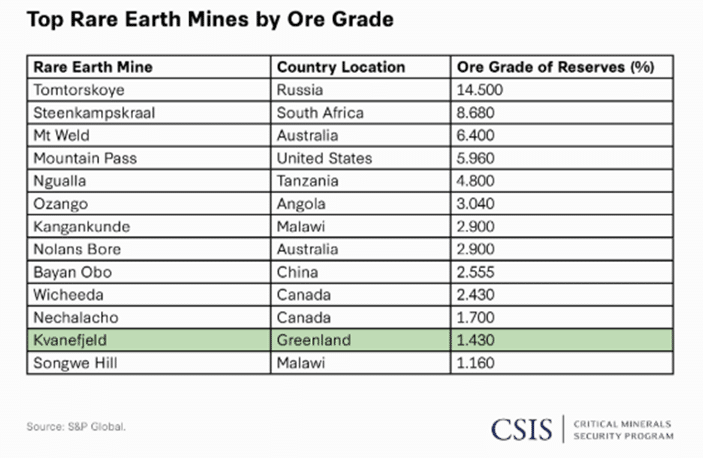

Other countries with significant rare earth reserves include Russia, South Africa, Australia, the United States, Tanzania, Angola, Malawi, Canada, and Greenland. Collectively, however, these countries account for only about 30% of global rare earth mining output. Large reserves do not automatically translate into production. In many cases, deposits remain underdeveloped due to high capital costs, regulatory hurdles, or technical challenges.

China is therefore the undisputed heavyweight—not just in the ground, but in actual mining and production. Even countries such as Vietnam, Russia, and Greenland, which hold millions of tonnes in estimated rare earth deposits, have yet to convert that potential into meaningful extraction.

This dynamic has brought rare earths back into the public spotlight. Recent coverage of President Trump’s interest in Greenland highlighted the territory’s strategic mineral potential. Greenland ranks eighth globally in rare earth reserves and is home to two of the world’s largest known deposits: Kvanefjeld and Tanbreez. To date, however, these deposits remain largely unmined due to the harsh Arctic climate, infrastructure limitations, and environmental concerns.

Refining: China’s Near-Monopoly

Mining is only the first step. The true choke point in the rare earth supply chain lies in refining and processing—the conversion of raw ore into oxides, metals, and magnetic alloys. This process is technically complex, capital intensive, and environmentally challenging. It is also where China’s dominance is most pronounced.

China is the only country that has built a fully integrated rare earth supply chain, often described as “mine to magnet.” It controls the vast majority of global separation and refining capacity, as well as downstream manufacturing of rare earth permanent magnets.

Even the United States, despite being a relatively large rare earth miner, exports over 95% of its raw rare earth concentrate to Asia—primarily China—for processing. For investors, this concentration cuts both ways. It reinforces the strategic value of rare earths and the urgency of developing non-Chinese supply chains, but it also means that any disruption within China—whether geopolitical, regulatory, or environmental—can reverberate quickly through global markets.

Geopolitics and National Security

Rare earth elements have been called “the vitamins of modern industry,” but they have also become a flashpoint in global geopolitics. Control over rare earth supply chains is now widely recognized as a national security issue, particularly as competition intensifies between the United States and China.

Discussions surrounding Greenland’s strategic importance to the United States and NATO have brought rare earths to the forefront, as major powers—including the U.S., China, Russia, and the European Union—seek influence over the Arctic and its resources. The logic is straightforward: rare earths are critical inputs for advanced technologies that underpin economic competitiveness, energy transitions, and military capability.

Stepping back from the geopolitical headlines, the core reality is simple: rare earth elements operate quietly in the background, but they are essential enablers of the modern, tech-driven economy.

Conclusion: What This Means for Investors

For investors, rare earth elements represent a sector where technology, geopolitics, and supply-chain fragility intersect. Several companies in the United States and Australia are actively attempting to gain market share and reduce Western dependence on China. Government support, long-term offtake agreements, and national security priorities all serve as potential tailwinds for these efforts.

That said, the primary headwind for Western producers remains environmental and regulatory intensity. Stricter environmental standards increase costs and slow development timelines—one of the very reasons rare earth mining migrated to China decades ago. Cleaner production improves sustainability and political acceptance, but it also makes competing on price more difficult.

The long-term outlook is therefore nuanced. Demand for rare earths is structurally rising, supply chains remain highly concentrated, and geopolitical incentives favor diversification away from China. These forces create opportunity—but not without volatility and execution risk.

For investors, the takeaway is not that rare earths are a short-term trade, but that they are a strategic industry worth monitoring closely. As global supply chains are reshaped and governments prioritize resilience over cost efficiency, rare earth elements are likely to remain at the center of industrial policy, technological progress, and investment opportunity for years to come.

DISCLOSURE: Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. The information provided is general in nature and should not be considered legal or tax advice. Consult an attorney, tax professional, or other advisor regarding your specific legal or tax situation. The items included in this publication are our opinion as of the date of this piece, not all encompassing, and are subject to change without notice. Any tax or legal advice contained in this communication is not intended as a thorough, in-depth analysis of specific issues, nor a substitute for a formal opinion, nor is it sufficient to avoid tax-related penalties.