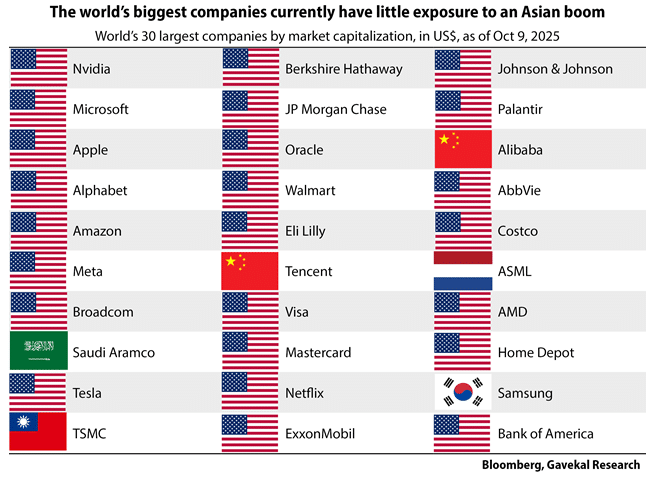

In mid-September, I asked which megatrends will reshape the global economy over the coming decade. Possible answers included the rollout of artificial intelligence and self-driving vehicles, the looming bankruptcy of Western welfare states, a structural bull market in Chinese equities, the second largest stock market in the world, and the growing economic integration of China, India and Russia, the first, third and fourth largest economies in the world in purchasing power parity terms.

Missing from these megatrends was the threat of a cold war-or worse, a hot war-between the US and China. Instead, there are a number of reasons to hope that the US-China relationship will not deteriorate, and will perhaps even improve, from here.

US-China relations started to deteriorate almost as soon as Xi Jinping arrived in power. Early in his first term, Xi started to push a "Made in China 2025" agenda that would see China transform itself from a client of large US multinationals-Boeing, GE, 3M, DuPont, Dow Chemical, Ford, GM-into a competitor. Suddenly, US corporates that until then had always advocated and lobbied for ever-stronger ties with China began to have second thoughts.

At the same time, following the second round of US quantitative easing, which Beijing blamed for causing higher global food and energy prices and triggering the Arab Spring, China announced that it was done with recycling its large trade surpluses into US treasuries. Instead, it would use its excess savings to build infrastructure across the Global South launching the One Belt, One Road program, the Silk Road Fund and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. And it would promote the renminbi as an alternative trading currency, and even as a potential reserve currency. None of this pleased the US one bit.

The US displeasure was manifest in 2018 when Donald Trump's first administration imposed an embargo on the sale of high-end semiconductors to China. This came as a shock to Beijing, which had little choice but to "take the punch;' and hope that a change of administration would lead to a shift in policy.

The Anchorage meeting of 2021 put such hopes to the sword. By 2021, Republicans and Democrats could no longer agree on the definitions of motherhood and apple pie; but in a highly partisan context, being "anti China'' had become the only non-partisan issue in Washington. So China took the 2021 punch, just as it had done three years before.

With little attractive alternative, China kept its head down, worked and invested in order to reduce its dependence on Western supply chains. So that when Trump returned to power in 2025 and took a swing not only at China, but also at Europe, Mexico, Canada, India, Brazil and others, China was the one country able to push back.

A tariff war duly followed. But when the US administration realized that Chinese export controls on rare earths and magnets had the potential to disrupt US weapons manufacturing. A compromise was reached in Geneva. Suddenly, mentions of Taiwan in the US press disappeared (as did visits by US politicians).

This climbdown wasn't all. The Pentagon leaked a spending review paper that argued for a retrenchment of US military projection to the Western hemisphere, even as Beijing ran roughshod over US objections to China's purchases of Russian energy, going as far as agreeing the construction of a new natural gas pipeline from Russia through Mongolia to China.

Finally, in perhaps the biggest tell of all, in the past two weeks US media especially Fox News and The Wall Street Journal-have been relentless in highlighting how China has stopped buying US soybeans, and about how China needs to start buying American soybeans again. This focus on soybeans in the weeks leading up to the planned Trump-Xi meeting in Seoul at the end of October is probably not a coincidence. Instead, it is likely an attempt by the US administration to set a low bar for the upcoming meeting.

When it comes to delivering concrete "wins," is there anything easier for Xi to give to Trump than the promise of more soybean purchases? A large soybean order would allow Trump to declare victory in the unfolding US-China cold war (perhaps even with a ticker-tape parade down Fifth Avenue over Thanksgiving?) and return the US-Sino relationship to a more productive setting for both countries. And just as success has many fathers, there are many possible explanations for this US change of heart:

US attempts to contain China technologically have failed, and may even have been counter-productive (necessity being the mother of invention and all that). This is a point made constantly by Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, and an argument that we have made repeatedly in the pages of our new Gavekal Technologies reports.

Whatever the reason, we still end up in the same place. When Trump and Xi sit down at the end of October, the chance of another Anchorage debacle is very small. On the contrary, expectations have now been set so low that the probability of Trump walking out of the meeting with a big smile and congratulating himself on a beautiful deal is very high.

Of course, whether the agreed-to deal ends up being worth a hill of beans remains to be seen. But the markets, and especially the Chinese markets, will likely cheer any meeting that ends on a positive tone.

DISCLOSURE: Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.