“Whenever I think of the past, it brings back so many memories.”

– Comedian Chris Wright

"The trouble with the world today is that the intelligent people are full of doubts while the stupid ones are full of confidence.”

– American poet Charles Bukowski

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

At the end of 2017, Evergreen initiated a special-edition EVA series with excerpts from David Hay’s upcoming book titled “Bubble 3.0: How Central Banks Created the Next Financial Crisis.” The EVA series ended in May 2020, when David finally unveiled his long-running thesis about the Fed’s “End Game”.

Over the past 15 months, David has been working to prep his book for print and has decided to share one chapter ahead of its release titled “The Anti-Bubble Years.” This chapter will run in two parts, with the second part scheduled to run next Friday.

Summary

The Anti-Bubble Years (Part I) by David Hay

Earlier this year, I shocked my eldest son by telling him that I had been a bond bull almost continually over the past four decades. Because he’s not quite forty himself, this means I have been an optimist about lower interest rates and, related to this, controlled inflation since before he was born. Due to the fact we’ve worked together at Evergreen Gavekal for almost twenty years, I was frankly surprised by his surprise. He then asked me why? What caused me to maintain a bullish stance on bonds for nearly all of the past forty years? That also caught me off-guard; accordingly, I thought it might make an interesting story…and one relevant to Bubble 3.0, the third enormous speculative frenzy of the last quarter-century.

First, though, I’d like to discuss the concept of anti-bubbles. Bubbles themselves now get tremendous amounts of press. Their counterparts, however, don’t. In my 42 years of financial market experience, anti-bubbles are where immense amount of wealth are made and bubbles are where they are lost.

Admittedly, the bond market does not leap to mind when you think about bubbles or their polar opposite—an asset class that has been in a long and/or ferocious bear market, what I and some others refer to as anti-bubbles. However, another central part of this book is that bonds today are arguably the biggest bubble of all-time. Realizing how much competition there is for that designation these days—such as from a crypto “currency” like Dogecoin—is why I wrote “arguably”.

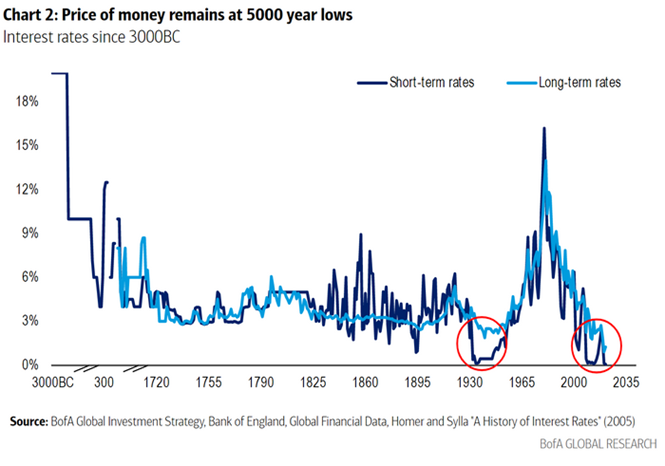

But when you recognize that interest rates are at a 5000-year low, I think it’s fair to say that bond prices are just a tad on the unusual side and have been for years. It’s also critical to be aware that when interest rates fall, bond prices rise. Thus, being at a multi-millennia low in rates means that bonds are also at a 5000-year peak in valuation. Now, I think that qualifies as a top contender for the biggest bubble ever!

Amazingly, though, this doesn’t preclude a long list of experts, many of whom I respect, from continuing to be bond bullish. To the point of this chapter, I was right there with them, at least until Covid struck. It was the Fed’s response to the pandemic that turned me—and turned me hard, as in, toward hard assets—and away from fixed-income. But, as usual, I’m getting ahead of myself. First, we need to go back, way back to when then- President Jimmy Carter made a crucial decision.

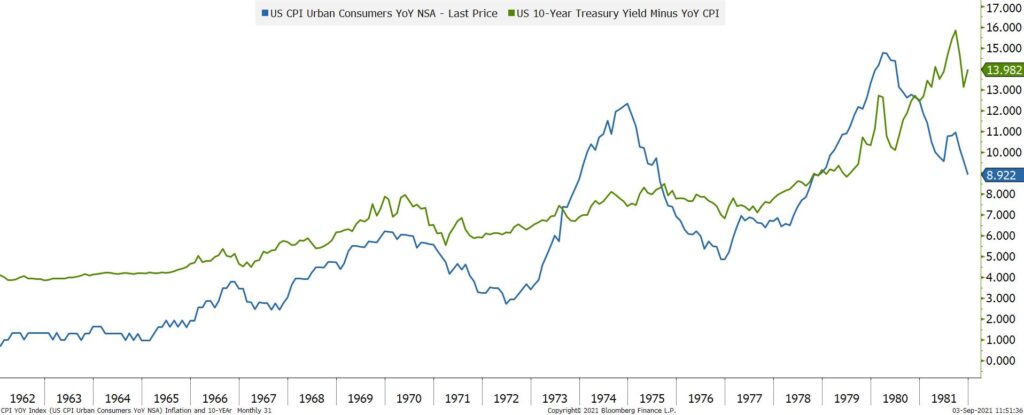

While inflation would erupt under Jimmy Carter, it was already in a jagged but decidedly upward trend in the US from 1966 to 1972 for a variety of reasons: the guns and butter policies of LBJ, increasing unionization, mounting political pressure on the Fed to let the economy run hot, and, the ultimate coup de grace, Richard Nixon’s removal of the Gold Standard in 1971.

Once the latter occurred, inflation was off to the races. The twin energy crises of the 1970s only caused it to run all the wilder. As the 1970s came to a close, the US CPI was screaming higher at a year-over-year rate of 13.3%. Shortly thereafter, it briefly receded due to draconian credit controls which were introduced in the winter of 1980, triggering a short but severe recession.

(This author entered the securities industry in early 1979, just in time to witness inflation and interest rates both going bonkers, to use a highly technical term. Later that year, a slightly more momentous event occurred than my employment by the former Wall Street firm of Dean Witter (long ago subsumed into Morgan Stanley): Jimmy Carter’s appointment of Paul Volcker as head of the Federal Reserve.)

In the presidential election year of 1980, the first half recession was political suicide for Jimmy Carter. Predictably, even though inflation fleetingly crashed down near zero, as soon as the credit restrictions were lifted the CPI was back in double-digits as the November election approached (in a flashback to the removal of Nixon’s wage and price controls nine years earlier). Also predictably, Ronald Reagan won in a landslide.

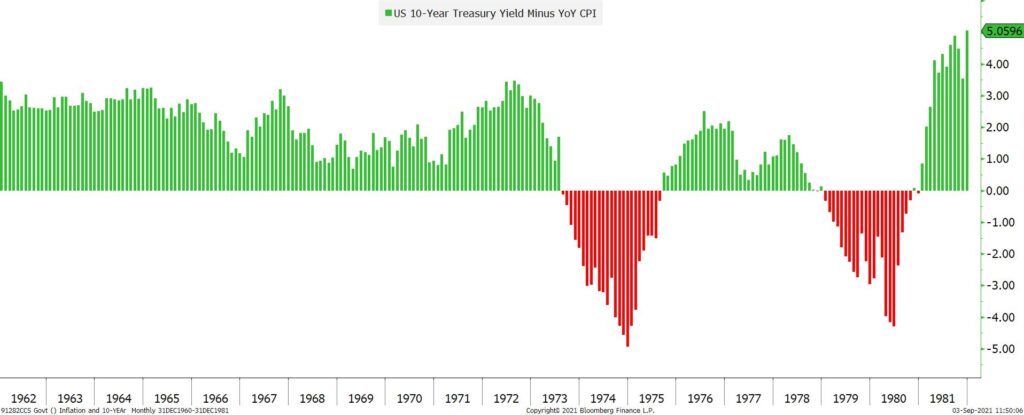

Mr. Reagan’s election did nothing to slow inflation initially. The CPI was still running at a double-digit rate early in 1981 and would stay above 10% for nearly the entire year. However, unlike the Fed chairmen who had preceded him for most of the 1970s, Mr. Volcker vowed to get ahead of the inflation curve. Previously, the Fed was constantly playing from behind, largely unable or unwilling to get its key interest rate weapon—the fed funds rate—above the CPI. Therefore, for most of the ‘70s, short-term interest rates were negligible to negative, after inflation, despite the fact they rose drastically over that decade.

By the end of 1980 and into 1981, it was a very different story. Mr. Volcker pushed the fed funds rate to near 20%. This in turn caused the prime rate (the key borrowing standard) to spike to the previously unimaginable level of 21% by June of 1981. Despite 12% inflation, the real fed funds rate (the stated rate less the CPI) was roughly 8%. This was a real rate of return—or cost of money, depending on whether you were a lender or borrower—never remotely seen in the US (with the exception of during the darkest days of the Great Depression when consumer prices were crashing).

Long-term treasury bond yields were in the mid-teens. Even tax-free bonds were yielding 14% or more (I vividly remember this era because I was buying as many as clients would allow). The period from 1966 to 1981 was without rival the worst bear market bonds had ever experienced. It was the ultimate anti-bubble in US history for the normally tranquil and defensive world of debt instruments.

The dark side of these extraordinarily high real interest rates was the worst recession since the 1930s, with unemployment spiking into double digits. The upside was an inflation collapse. By the end of 1982, the CPI was sub-4%, a level not seen since the Nixon wage and price controls. Unlike then, when the inflation contraction was both artificial and brief, this one stuck.

The inflation implosion allowed the Fed to start drastically slashing interest rates. As 1982 came to a close, the fed funds rate was down to 9%; this was the lowest it had been since 1979. But there was a huge difference in real terms: Inflation was also at 9% in 1979 and rising sharply. Consequently, the real return was 0. This provided a strong incentive for businesses and consumers to keep borrowing and buying hard assets, like real estate and commodities with the proceeds, helping to stoke the inflationary fires.

However, by the end of 1982 the real rate was a still very stiff (or munificent, for lenders) 5%. Therefore, even though the after-inflation rate had come down from its most punitive levels (for borrowers) it remained extremely elevated. Regardless, the collapse in both nominal interest rates and inflation triggered one of the most dramatic financial events in the history of global stock markets. But a bit more market history is in order to fully appreciate what happened in August of 1982.

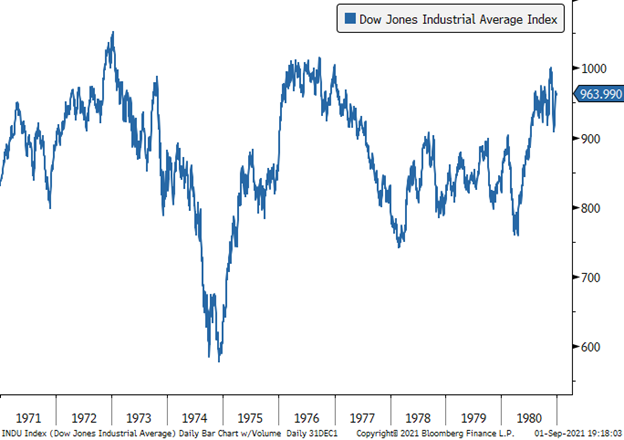

The Dow Jones Industrial average had first essentially hit 1000 in 1966 (995). A sideways market then ensued into the early 1970s, with the Dow barely breaking above 1000 (1052) in 1973. This meant that in after-inflation terms the stock market had generated seven years of negative returns, at least before factoring in dividends. Even with those included, the so-called total return of the Dow was 36.4% from 1966 to 1973.* However, inflation averaged 4.23% per year during this period; thus, the after-inflation return, inclusive of dividends, was a meager 0.4% annually. (The S&P 500 fared better with a real dividend plus price appreciation rate of 21% or 2.75% per year in real terms.) Then things really got ugly.

The Arab oil embargo of October 1973 caused energy prices and inflation to do a moonshot. By the summer of 1974, oil prices had tripled, causing the CPI and the fed funds rate to both hit 12% (note that, once again, even an extremely high headline, or nominal, interest rate was actually zero relative to inflation). The venerable Dow was basically cut in half by this twin gut-punch. Nixon’s Watergate scandal that drove him from office in August of 1974 only added to the national nightmare, as incoming President Gerald Ford would soon call this period.

The Arab oil embargo ended in March of 1974 but stocks kept falling regardless. Even once oil was flowing from the Mideast again, crude prices remained about four times higher than they had been in 1972. Surprisingly, the economy only contracted by 0.5% in 1974 despite the oil shock but that didn’t prevent the worst bear market since the 1930s.

When the market finally hit bottom in December of 1974, the price-earnings ratio on the Dow was down to a microscopic six, thus fully qualifying as a true anti-bubble (the inverse of the conditions prevailing in 2021). This meant the reciprocal of the P/E ratio, the earnings yield, on the Dow was basically 16%. This was the highest it had been since the aftermath of WWII when many pundits believed the US would enter another depression. (This was due to the belief that there would be mass unemployment as a result of millions of discharged servicemen along with the ultimate “fiscal cliff” as federal government spending collapsed with the cessation of hostilities.)

By 1975, inflation had cooled and stocks began a cyclical recovery. The Dow had increased by 76% from the 1974 nadir to the early 1976 peak at 1015. With dividends included, the total return was 96%%. However, the 1973 high of 1052 was not broken for many years to come. As a result, the late 1970s inflation surge would push stock investors’ real return even further into the red.

*Intriguingly, the 4.23% average inflation rate from 1966 to early 1972 occurred while the US was still on the Gold Standard almost the entire time.

The next trough was hit in August of 1982 during the aforementioned severe recession induced by Paul Volcker’s do-or-die war on inflation. At that point, the inflation-adjusted total return on the Dow and S&P 500 since 1966 was a pathetic minus 45% and negative 29%, respectively, -3.6% and -2.1% annually. (On a pure price basis, the Dow lost almost 230% relative to inflation while the S&P eroded 195%. The yawning gap between these real return numbers shows the power of dividends over an extended period. But that was when dividends were far higher than they are today.)

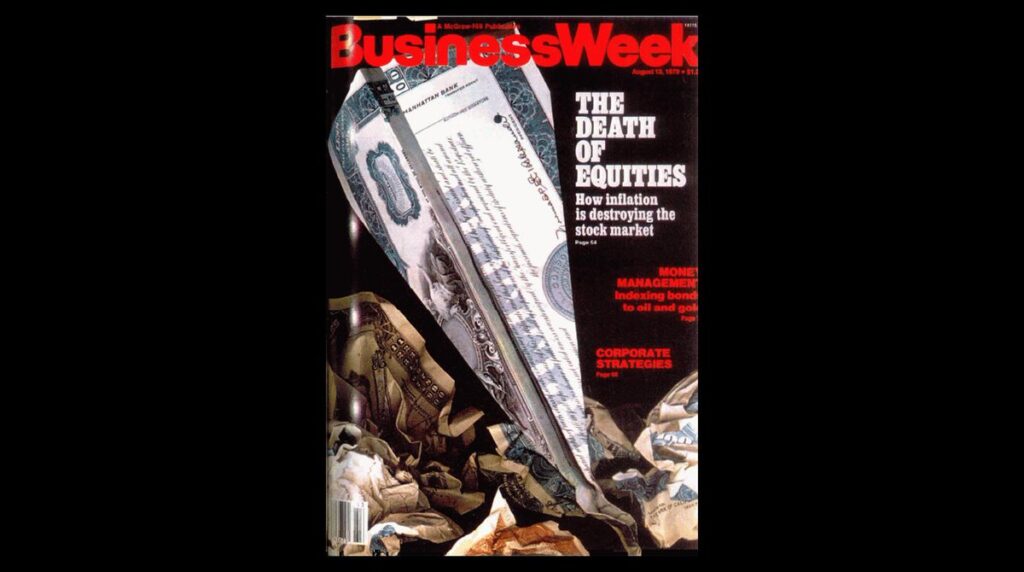

It was during this era that Business Week magazine, as it was called back then (now Bloomberg Business Week), ran its infamous “Death of Equities” cover story. With the passage of time, it has become roundly lampooned and frequently cited as a classic contrarian buy-signal. Forty years later, the magazine conceded it was still catching flak over its bearish message.

However, to be fair, it ran on August 19th, 1979, and it factually warned that inflation was greatly harming the stock market. So factual in fact, that it was merely stating the obvious. And for the next three years stocks continued to struggle. The total net-of-inflation return on the Dow from when the story ran until August of 1982 was a decidedly negative 20%, or about -6% annually. In other words, it was a pretty decent call and certainly not deserving of such enduring historical derision. (Many far more poorly timed cover stories have cursed other big-name publications, especially The Economist.)

Moreover, the basic point of the article was spot-on: Inflation was enemy number one for stocks. It is no coincidence that it was when the CPI became unanchored in the mid-1960s—and was increasingly out-of-control all the way until the early 1980s—that the stock market performed so miserably. Similarly, it wasn’t a fluke that stocks bottomed almost precisely three years after “The Death Of Equities” cover story, at a time when investors worldwide were waking up to the reality that a scourge they never thought would end was indeed being largely eradicated. The twin collapse by interest rates and inflation provided the rocket fuel for “The Great Lift-off” in stocks and bonds.

The stock market surge that began in August of 1982 would go down in the history books for both its duration and its magnitude. Five years after its birth, the raging bull had surged from 776 to 2722 by August of 1987. It would arguably last until the spring of 2000 when the enormous bubble in tech stocks met its pin-prick. The reason that it was arguable is what happened in October of 1987 when the market fell nearly 40% in a matter of weeks and almost 23% on Black Monday, October 19th, alone. (As an interesting side-note, despite the late year crash, the Dow finished plus 5 1/2% for all of 1987; it had been up a bodacious 44% for the year when it hit its August apex.)

Yet, as with the Covid crash in March of 2020, this dramatic interruption of the great bull market was so brief that it’s hard to classify as a true bear market. In hindsight, it was a nasty correction which didn’t interrupt the long-term up-trend.

By March of 2000, when tech turned into a wreck, both the Dow and the S&P 500 had returned a spectacular 19.6% annually, including dividends, since the August 1982 trough. Even after inflation, returns were in the mid-teens. The NASDAQ, the object of the late 1990s bubble, had produce a 21.4% annual return, including returns of 40.2% and 86% in 1998 and 1999, respectively.

As usual, investors projected these returns into the new decade; instead, the first decade of this century/millennium saw a negative annual return of 1% on the S&P and 4.9% on the NASDAQ. On an inflation-adjusted basis, it was an even more depressing loss per year of 3.4% and 7.3%, respectively. (Interestingly, after the exceptional returns since 2009, despite sub-par economic growth and America’s stunning loss of stature, investors are once again projecting unrealistically high returns throughout this decade.)

The epic bull run from 1982 to early 2000 was the biggest of all-time. But it wasn’t just stocks that were superstars. As mentioned earlier, the bond market was in its own way just as spectacular. Thirty-year maturity zero-coupon treasury bonds bestowed upon the handful of intrepid investors who were willing to buy them at their yield peak in 1981--when they were derisively called “certificates of confiscation”—a per year return of 17.6%. On a risk-adjusted basis versus stocks this beat the S&P 500 handily. The ratio of annual return vs. volatility for bonds was 2.27 vs. just 1.36 for the S&P 500. (Bonds are less volatile, or risky, than stocks and, thus, are expected to have a lower return but with much milder fluctuations; this calculation makes that adjustment.)

There is no doubt the collapse in yields during the period from 1982 to 2000 turbo-charged the great bull market. This was despite the fact that long-term treasury bonds were still yielding around 6% in March of 2000 when the nearly 18-year bull market finally expired. This is contrast to less than 2% in August of 2021, as I write this chapter.

In many ways, conditions today seem the polar opposite of what they were forty years ago as bond and stocks were poised to make their historic runs. Yet, investors are positioned as if it’s 1982 all over again. In the next EVA, we’ll consider how likely a repeat performance is based on what’s happening to that highly influential, but long-slumbering, force called inflation.

To be continued next week…

David Hay

Co-Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.