“[Accommodative policy] for too long could... encourage excessive risk-taking and thus undermine financial stability.”

-JANET YELLEN, Federal Reserve Chair

Market cycles tend to swing between two extremes: periods of growth and decline. On any given day, a market can be up or down; however, generally, we bucket long-term periods of performance into “bull” and “bear” terms. It should come as no surprise to those who keep their eyes fixed on the happenings of the market that we have been stuck on one side of this polarizing pendulum for a very (very) long time. In fact, there have been few instances in history where the market has experienced greater sustained growth.

Overarching market performance is driven by many complicated factors so it’s difficult to call out a specific catalyst as singularly important in contributing to these extremes. However, in the case of this great bull market, the main prod is pretty obvious: central banks.

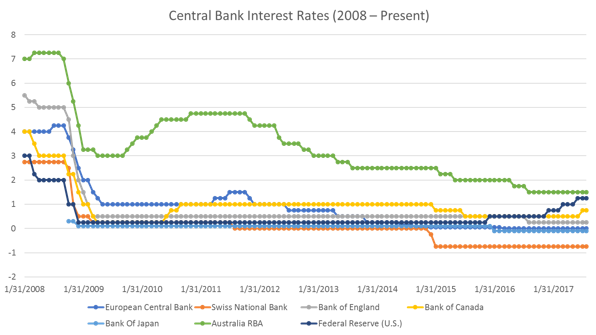

Specifically, several central banks around the globe drove their interest rates to artificially low levels to support growth in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis. The chart below shows just how far (and quickly) these rates came down:

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

But what has been good for big business over the past decade has not necessarily been good for everyone else. Small businesses have suffered in their ability to access less expensive capital as easily as their counterparts, which has had the unintended effect of stunting the foundation this country was built on: true American enterprise.

This week’s Gavekal EVA comes from a good friend and partner of Evergreen Gavekal, Charles Gave. While the piece is relatively short compared to many EVAs we run, the content on low interest rates is dense and full of relevant wisdom we think you’ll enjoy.

Michael Johnston

Marketing & Communications Manager

Zero interest rates have made a great many people a great deal richer. But paradoxically they have strangled wealth creation. The reason for this is that enterprise is overwhelmingly a phenomenon found among smaller companies. Among big companies it is a rare quality. Quite simply, the overriding goal of every big company is to transform itself into a monopoly, so it can move away from having to earn its profits towards collecting risk-free rents. And for a big company to become a monopoly, smaller more enterprising companies must be denied access to capital. Zero interest rates achieve exactly this objective.

It works like this. In an economy there are two interest rates:

According to the great 19th century Swedish economist Knut Wicksell, the economic cycle is created by the differences between these two rates.

Now, let us assume that the market rate is much too low at 1%, either because the banking system is misjudging the real cost of capital or because central bankers mistakenly believe they can boost economic growth by tampering with short rates. What will happen?

A good number of existing assets, whether buildings or companies or even private jets, will have a return higher than 1%. It will then pay to borrow at 1% in order buy an asset yielding, say, 3%. But of course the people who can borrow are, pretty much by definition, those who already own assets—big companies and the rich—and not those who are trying to build assets—entrepreneurs. So banks will extend their lending capacity not to those who invest, but to those who speculate.

The prices of existing assets will go up tremendously, but not the capital stock of the economy. And since capital spending is not increasing, productivity growth will fall, and with it the structural growth rate of the economy.

Because over the long term the marginal growth rate of the economy equals the marginal growth rate of profits, sooner or later the marginal growth rate of profits (which is equal to the natural rate) will fall below the market rate, even if the market rate is very low. On that day, the fellows who have borrowed at 1% to buy existing assets will be unable to service their debts. The result will be a massive financial crisis, as described by Irving Fisher in the 1930s.

Now let us imagine that a wise and prudent central bank keeps short rates at 4%. There will be no incentive for speculators to borrow at 4% to buy existing assets yielding 3%. In this case, the only people who will borrow will be those who expect a marginal return on invested capital higher than 4%—entrepreneurs. Their borrowing will go to fund investment in new assets, productivity will go up, and the structural growth rate of the economy will follow, which will make repaying the debt easier.

Ensuring that the market rate is no lower than the natural rate is the only way to prevent unproductive leverage from developing in an economic system. It is also the way to make sure that creative destruction is actually taking place and that savings are employed profitably, since companies with low returns will not be able to access the capital they need to survive.

In today’s world, those who can borrow to buy existing assets are the big companies with positive cash-flows and little growth, and their shareholders, the rich. They borrow to buy back their own shares or other readily available assets, such as existing buildings. This increases the unproductive leverage in the system, whether through the leverage of big and mature companies, through the leveraged clients of investment banks, or through the big leveraged buyout firms, which would not be able to exist and prosper if rates were at 4% or 5%.

In contrast, entrepreneurs, the people the economy relies on to build tomorrow’s assets, are unable to obtain capital, since the banking system finds it much less risky to lend to GE to buy back its own shares than to lend to some lunatic with a bizarre project to build a better mousetrap, or a new quantum computer, or whatever it happens to be. Needless to say, this combination of increasing financial leverage and declining investment in productive assets greatly increases the vulnerability of ordinary workers and the poor when the next downturn occurs.

So, to conclude:

It is hard to imagine a more disastrous policy.

Scared by what they have done in keeping interest rates at stupidly low levels for the last 20 years, developed world central banks have decided to buy the resulting overvalued assets themselves in order to prevent a ferocious bout of debt liquidation. At best, their policy solves nothing and just buys time.

The only place in the world where interest rates are at more or less sensible levels is in emerging Asia, where the People’s Bank of China is attempting to organize a system resilient enough to survive the impending deflationary bust in the developed world. Good luck to them.

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

CHANGED HIGHLIGHTED IN BOLD.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.