A political deal may have been cobbled together to keep the US government operating until November, but on Monday treasuries kept selling off. As investors game out what the funding deal means for monetary policy, they are unlikely to find succor in the US’s poor fiscal outlook.

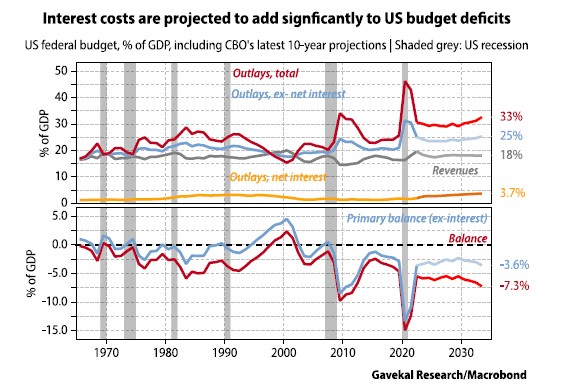

Some analysts blame this fiscal deterioration on past tax cuts, but government revenues have been stable at 15-20% of GDP since the 1960s. Today, revenues are at the high end of that range and not expected to vary much in the next decade. The real issue is rising government outlays, with two types standing out: (i) public pension and health care spending and (ii) interest expenses. With bond yields pushing higher, the second factor is worsening by the day.

As is well known by now, an aging population will increase outlays for Social Security and major health care programs, from 10.9% of GDP this year to 12.6% of GDP in 2033, according to the latest projections from the Congressional Budget Office. However, with other types of government spending projected (but not guaranteed) to be restrained, the primary balance (excluding interest costs) is expected to be stable at around -3% of GDP for the next decade, give or take 60bp in any given year. That is nothing to be proud of, especially at a time when unemployment is near record lows.

Add in rising interest costs, however, and the overall fiscal outlook becomes downright worrying. Louis has warned of this for a while (see The Three Prices: An Update On US Treasury Yields), but his concerns have not been a major worry for the broader market. Indeed, the US’s total budget deficit (including interest) is projected to run at almost double the primary deficit for the coming years, or around -6% of GDP from today through 2030. It is then projected to blow out to more than -7% by 2033.

A decade from now, interest expenses are projected to total 3.7% of GDP, exceeding “discretionary” spending on defense (2.8%) and non-defense programs (3.2%). As an aside, it strikes me as odd to call public pension and healthcare programs “mandatory”, while dubbing defense a “discretionary” activity, when a core role of the government is to provide national defense. The real point is that interest costs are becoming one of the biggest components of government outlays, as shown in the chart on the prior page.

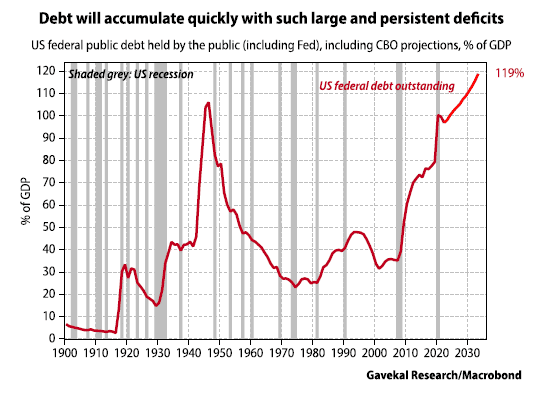

Such large and sustained deficits mean that debt will accumulate rapidly, with the CBO projecting a rise in the US’s debt-to-GDP ratio from about 100% today to almost 120% in 10 years time. More worryingly, the CBO made these projections in May, when bond yields were some100bp lower. If yields hold up, or rise further, the next set of projections will be even worse.

What happens when r > g?

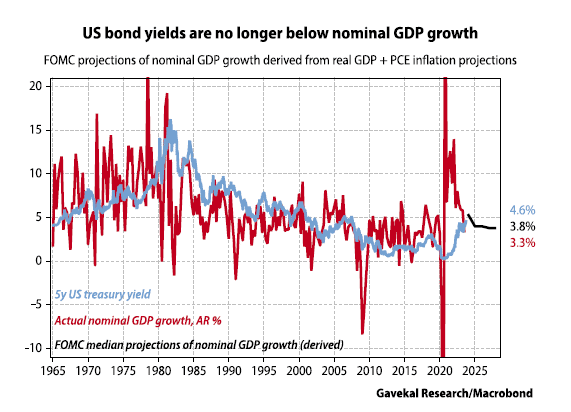

The rise in bond yields is concerning given that it has coincided with a decline in nominal growth rates. When interest rates (r) are above the nominal growth rate (g), interest costs rise relative to GDP. And if that interest is financed with additional debt, interest alone will increase the debt-to-GDP ratio, even if the primary budget is balanced. Add in a primary budget deficit, and the outlook gets worse still. Absent a change of policy, on current trends for interest rates and nominal growth such a “debt trap” dynamic seems set to play out.

This situation marks a change of circumstances, since most of the pandemic period saw low interest rates and high nominal GDP growth (r < g). Budget deficits blew out due to large-scale primary deficit spending, even as benign interest rate dynamics kept the debt sustainable. In recent months, however, nominal GDP growth has slowed while yields have risen, such that rates now exceed nominal growth (r > g). (Five-year treasury yields are used in the chart overleaf because the average maturity of outstanding treasuries has ranged from 4-6 years since the 1990s).

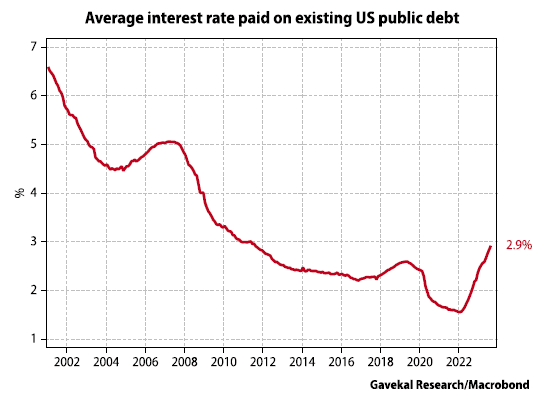

Actual interest rates paid by the US government will rise gradually as it issues new debt to refinance maturing debt, pay interest on existing debt, and finance ongoing primary deficits. But it won’t be too gradual given the scale of primary deficits ahead, the fact that the average maturity on existing debt is not that long, and given significant exposure to short-term rates (either directly, or via the Federal Reserve, which has kindly converted a bunch of US bonds into zero-duration, interest-bearing liabilities of the consolidated government—more on this in part two). The bottom line is that while there is a lag, rising market rates will eventually translate into higher interest rates paid on government debt—as is already starting to happen (see chart below). And that will raise more questions about the sustainability of US debt.

The US’s fiscal outlook will vary if the recent trend of rising nominal interest rates and slowing nominal growth continues apace. Consider three scenarios:

Whatever scenario unfolds, the fiscal outlook will be poor due to ongoing primary deficits. But interest rates will put more pressure on the government to act, should scenario #1—or even scenario #2—prevail.

What can the US government do?

With debt funding becoming increasingly costly, how will the US government respond, if at all? There are a few options:

DISCLOSURE: Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.