“The most common cause of low prices is pessimism…We want to do business in such an environment, not because we like pessimism but because we like the prices it produces.”

–WARREN BUFFETT

At the beginning of 2018, we initiated a new EVA series titled “Bubble 3.0” with excerpts from David Hay’s upcoming book tentatively titled “Bubble 3.0: How Central Banks Created the Next Financial Crisis”.*

If you are just joining us in the middle of this ongoing series, which will eventually culminate in a full-length publication, please take a few moments to review the prior installments in the series:

This week, the Federal Reserve was front-and-center in the market, as two little words from Fed Chairman Jerome Powell sent the S&P up 2.3% on Wednesday. Those two words – “just below” – gave investors hope that the central bank might be closer than previously assumed to ending its push to drive up interest rates. Whether the sentiment holds, or whether it was simply Mr. Powell’s best attempt at job preservation in the face of increased POTUS scrutiny, is anyone’s best guess. What’s not up for debate – at least in our opinion – is that the slide in market values over the past couple months is emblematic of a longer-term reality created by the same folks (i.e. the Fed) who fueled the asset price inflation over the last 10-years.

True to recent form, Wednesday’s Fed comments might have bolstered the likelihood of the year-end rally we predicted in last week’s EVA. But – as also stated in last week’s EVA – we believe it’s a rally worth selling into because it’s very hard to buy low if you don’t sell high.

*We do realize the book version will require significant revision to modify it from its current topical form.

BUBBLE 3.0: THE UPSIDE OF DOWNSIDE (CHAPTER 7)

The pain before the gain.

Because I’ve been in the investment business longer than a lot of EVA readers have been alive, I can personally attest that bull markets are much more fun than bear markets. On that point, this bull has been stomping for so long that many financial professionals have never seen a deep and lasting bear market. Recently, I met with a bright young broker from one of the leading Wall Street firms who has been “in the business” for 5 ½ years. He was shrewd enough to admit he had no idea what it would be like to live through a serious market decline, and he was also wise enough to realize he would have to—possibly sooner than later.

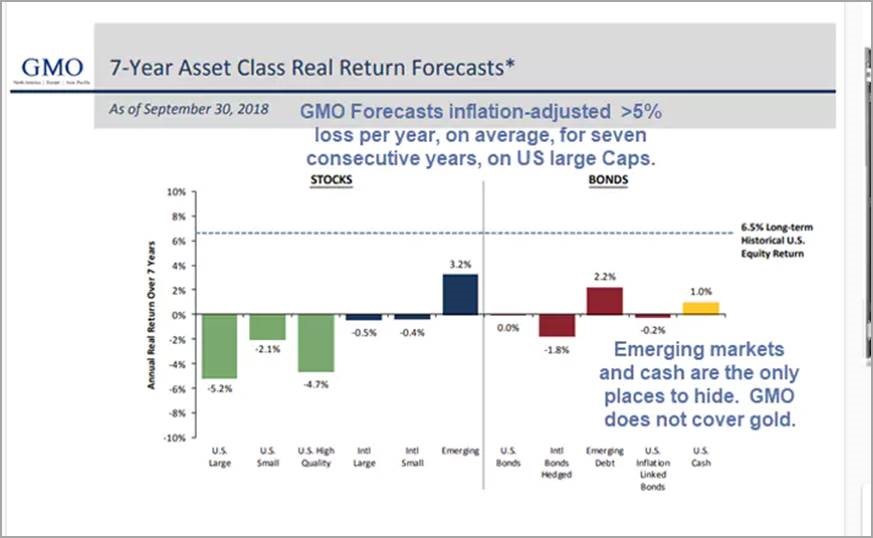

Previous EVAs have often cited the long-term return forecasts by the Boston-based money management giant, GMO. As the S&P has steadily risen from undervalued back in 2009 to fairly valued by 2012 to overvalued by 2014 to extraordinarily pricey by the summer of this year, GMO has methodically lowered their return expectations over the next seven years. The reason you should care about what GMO has to say on this subject is because they have one of the finest forecasting records in, once again, “the business”.

Per the below chart, their forecast through 2025 is rather sobering reading. Even though these are real, or after-inflation, numbers the implications, if they’re right, are enormous. This is particularly true for the tens of millions of Baby Boomers who need to live on the fruits of their portfolios.

Source: GMO as of 9/30/2018

Source: GMO as of 9/30/2018

As you can see, what they are projecting is anything but fruitful. Essentially, with a 50/50 mix of US stocks and bonds, GMO is looking for around a 2 ½% average annual negative return, inclusive of inflation.

One of Warren Buffett’s classic adages, “Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful” is predicated upon a crucial and rather obvious notion: you need to have cash on-hand to capitalize on others’ fears. But often, people become too complacent during boom times and allow their capital to remain in investment sectors, areas, or asset classes that are way beyond their sell-by date. Moreover, there is a strong and highly destructive tendency to move funds from underperforming vehicles into the hottest areas which then sets the stage for actual losses once the sky-rocketing sector, style, or stock inevitably succumbs to the laws of gravity.

If there is a devil-like being at work in the financial world, one of his nastiest tricks is making the most dangerous (i.e., grossly over-priced) asset classes look irresistibly attractive. Often, these slices of the investment universe have been generating outrageous returns for several years. The action in tech stocks back in the late 1990s was a graphic, though long ago, example of this. More recently, it has been the relentless rise in the S&P 500, with nary a single down year for nearly a decade. (As I write these words, in late November of 2018, this streak is in jeopardy. However, there’s still a good chance we will see ten consecutive up-years in the US stock market for the first time in recorded history—going all the way back to when shares were traded under a Buttonwood tree in New York shortly after the Revolutionary War.)

Bull markets, especially when they are particularly powerful and/or long-lasting, create a situation where investors become afraid to sell. We humans have been programmed over the eons to pursue activities which provide an immediate reward and avoid those that produce near-term pain or disappointment. That reality has helped us survive endless adversities (why it is we keep voting for our feckless politicians would seem to be an exception to this rule). It goes against every helix of our DNA to pull out of an activity that’s earning money even when wisenheimers like this author trot out a copious collection of charts and graphs to show that the S&P 500 circa late 2018 is dangerously inflated.

Thus, in a way, late-stage bull markets become like an elaborate con job. Perhaps some older readers of this newsletter might recall the entertaining film from the early 1970s, starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, “The Sting”. Messrs. Newman and Redford played thoroughly likeable con men who came up with an elaborate scheme to bilk a rich crime boss, played by Robert Shaw. The key to making their ploy work was to let their mark win. Once he banked a bunch of easy money, he was ripe for the plucking.

And so it goes with investors. When we’re sitting on years and years of double-digit gains, we become convinced that: A) the market is safe and B) the high returns will continue. As I’ve written before, in these situations investors act as though the lavish profits they’ve “earned” in recent years are somehow securely in the bank. They lose sight of the historical fact that returns during late-stage bull markets are about as lasting as a politician’s campaign promises. In reality, those gains tend to be wiped away almost overnight and the more inflated the market has become, the more years of “in the bank” gains are suddenly repossessed.

Frankly, most of the foregoing has fallen on deaf ears—until recently, that is, starting in early October to be specific. While no one could rightfully call what happened in October of this year a crash, or even a crashette, it nonetheless has catalyzed some serious repricing of risk. Additionally, it got me once again thinking back to another October, 31 years ago.

Flash crash flashback.

As noted in earlier Bubble 3.0 chapters, the 1987 crash was the first time that computers played a starring role in a major market collapse. Since then, of course, we’ve seen a number of those computer-driven cliff dives, although they’ve been limited to, thus far, the “flash crash” variety. These now-you-see-them, now-you-don’t panics happened in 2010, 2011, and 2015. In the latter instance, during August of that year, one ironically classified “low-volatility” ETF plunged 43% in less than an hour!!!

Today, as we all know, or at least we should, computer- or algorithm-based trading is dominant to a far greater degree than it was in 1987. Estimates are that these now represent 80% to 90% of New York Stock Exchange volumes. What is less well understood is that these systems generally don’t try to anticipate the future, as financial markets typically have in the past.

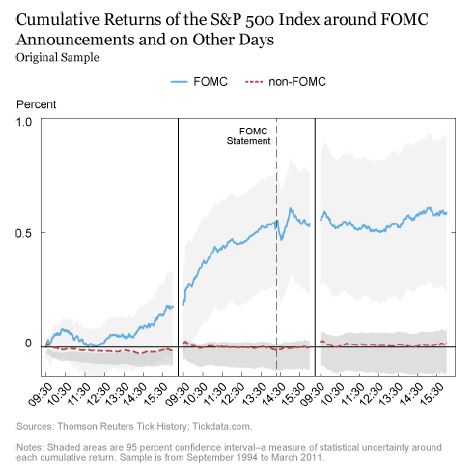

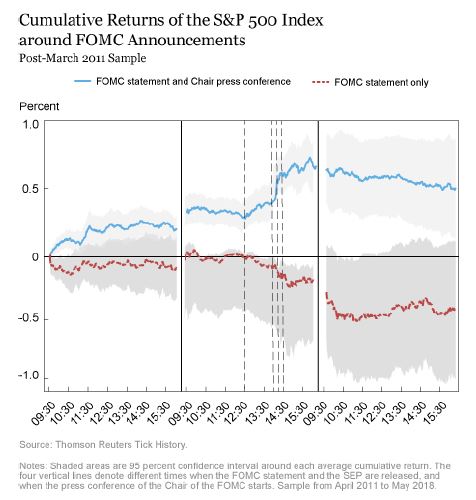

For example, if certain words in Fed press releases have led to market rallies, the same relationship is projected by the machines to happen again. One fascinating factoid in this regard is how much more the market has risen, like 80% of all returns, on Fed press conference days—even if those brought rate hikes—than it has the rest of the time. But don’t ask me to explain why. My only insight is that it simply shows that perhaps the only force driving the stock market these days that is more powerful than the “algos” and computers is the Fed.

Source: Liberty Street Economics as of 11/26/2018

Source: Liberty Street Economics as of 11/26/2018

This is definitely not how markets formerly behaved. As the celebrated economist Paul Samuelson once quipped, the stock market at one time had discounted nine of the last five recessions. In my opinion, the enormity of this shift has not been even close to fully appreciated. Most investors, in my view, continue to believe the market’s discounting mechanism is largely unchanged. Yet, as my astute partner Louis Gave--founder of the acclaimed institutional research firm Gavekal---has repeatedly pointed out, this is decidedly not the case. Rather than a market driven by myriad individuals spending endless hours analyzing economic, corporate, and geopolitical information, most of the movements these days are caused by the way in which computers react to current news events. This is not to say research isn’t still conducted but rather that it is overwhelmed by computerized-trading and, of course, passive investing.

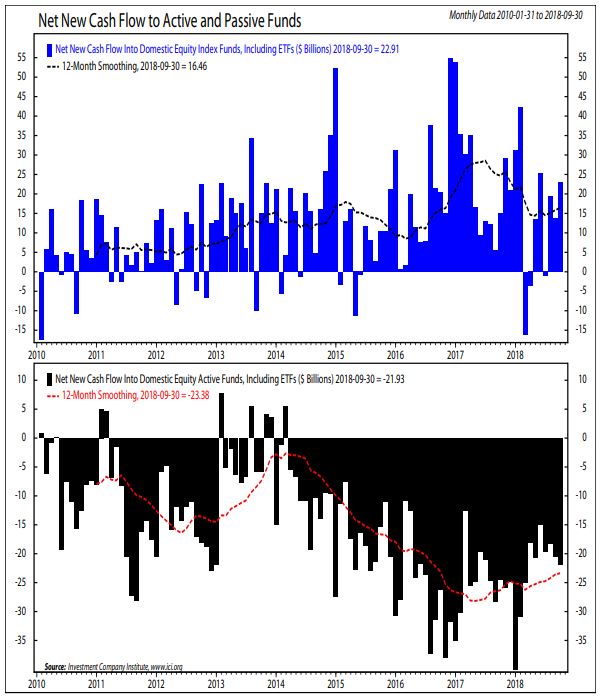

It’s common knowledge that the active investing community has been losing hundreds of billions, if not trillions, to its passive counterparts over the past two decades. The chart below makes that abundantly clear, courtesy of Ned Davis, founder of his eponymous firm.

Source: Ned Davis Research as of 11/21/2018

Source: Ned Davis Research as of 11/21/2018

By definition, there is no research performed by these index-type vehicles. In the “good old days”, the assumption was this was not a problem since markets were dominated by active managers who performed intensive analysis. This was the cornerstone of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) which, in turn, was, and still is, the cornerstone of passive investing. (Even back then, markets would become highly inefficient during bubbles and anti-bubbles—i.e., panics—which is why stock prices have always been more volatile than underlying fundamentals would indicate.)

But think deeply about current conditions in this regard. Active managers are no longer the elephants, they are the fleas. The monster pachyderms today are computers and passive funds. In other words, most money now is pushed around by entities that are not conducting much forward-looking research, if any at all. If that doesn’t raise red flags in your mind, you are way too invested—literally—in the current “don’t worry, be happy” mindset of the moment (though, admittedly, there does seem to be a jarring wake-up call ringing these days).

For years and years, this paradigm has been investment nirvana, at least for all those who have gone with the flow. The computers have almost exclusively been on the buy-side due to things like serial quantitative easings (QEs) from the planet’s central bankers, massive and deficit-financed corporate tax cuts, mostly rising earnings (especially in the US), the highest profit margins in history (again, in the US), and, most important of all, zero, and even negative, interest rates that made almost every risk-asset (like stocks) look irresistible.

Since early October, however, there is definitely a tide-shift underway. The uncanny string of events breaking the right way, particularly for the S&P and NASDAQ, has been broken. A key flow reverser is that interest rates have staged a comeback in many countries, especially the US, while the overall tone of headlines has become much more mixed, with a noticeable negative skew to them of late.

Consequently, the computers are no longer constantly churning out buy orders whenever there’s a dip. Instead, it appears as though their programs are concluding it’s now time to sell the rallies. This is a radical departure from the process that’s been in place for years and has played such a vital role in creating Bubble 3.0, also known (by moi) as the Biggest Bubble Ever and, most dangerous of all, the Longest Bubble Ever. It’s the length that has particularly duped investors into believing the stock market is no longer a volatile beast, capable of destroying vast amounts of wealth in breathtakingly short-order.

Even though October of this year didn’t produce a crash, it’s strange that the weakness experienced last month has continued into November. Of unique peculiarity was the weakness seen during Thanksgiving week, which normally tends to be levitated by holiday-related good cheer. This in no way precludes the cherished “Santa Claus Rally” which seems to be in the process of unfolding this week. Regardless, it is fair to say that what were exceptionally favorable conditions at the start of 2018 have deteriorated markedly. As a result, a seriously down-market year in 2019 looks much more plausible than it did just seven weeks ago.

But let’s now try to accentuate the positive…

What about that upside stuff?

If my belief that Bubble 3.0 is rapidly deflating is correct, this is actually great news for prudent investors—like those who systematically reduce risk late in a bull market. The CNBC regular and exquisitely articulate Jim Grant, proud bearer of his trademark bow-ties, is referring to what we are going through now as “a value restoration process”. I couldn’t agree more and it’s been long overdue.

To best illustrate this point, let’s once again return to bonds and interest rates, a kissin’ cousin pair of topics that I addressed in detail in the September 21st EVA. While it beggars the imagination, I suspect a handful of EVA readers may have missed the bond factoid we cited in last week’s special edition “Did You Know?” EVA. Specifically, I am referring to the item on the past six-year return from the main bond market benchmark, the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index, which was been a less than titillating 1.3% per annum (it’s also less than the inflation rate over that timeframe).

The reality is most financial assets are owned, directly or indirectly, by the Baby Boomer generation, with a decent slice still held by the parental generation thereof (though with an accelerating transfer process under way due to the efforts of the Grim Reaper). Most of the former and nearly all of the latter need to invest fairly conservatively and with an income orientation, especially for the growing number that are presently living off their capital. Bonds typically cover those investment bases but for years now when it comes to generating cash, high-quality fixed-income has been a dud—as in a 1.3% a year dud. But that was then and this is, well, not then.

The great news for risk-averse and income-needy investors is that these days you can lock in 3% per annum for several years with the safest of bond vehicles. Admittedly, 3% isn’t a lavish return but it sure beats 1.3%. Moreover, if the folks at GMO are right, it’s going to vastly outperform the total earnings from stocks over the next seven years. (In Evergreen’s view, a 12-month treasury could be one of the best performers in 2019 and, actually, that’s already been true in 2018. As a related side note, per Ned Davis Research, 2018 is on track to be the first year since 1972 with nary an asset class returning 5%, though that could change by 12/31.)

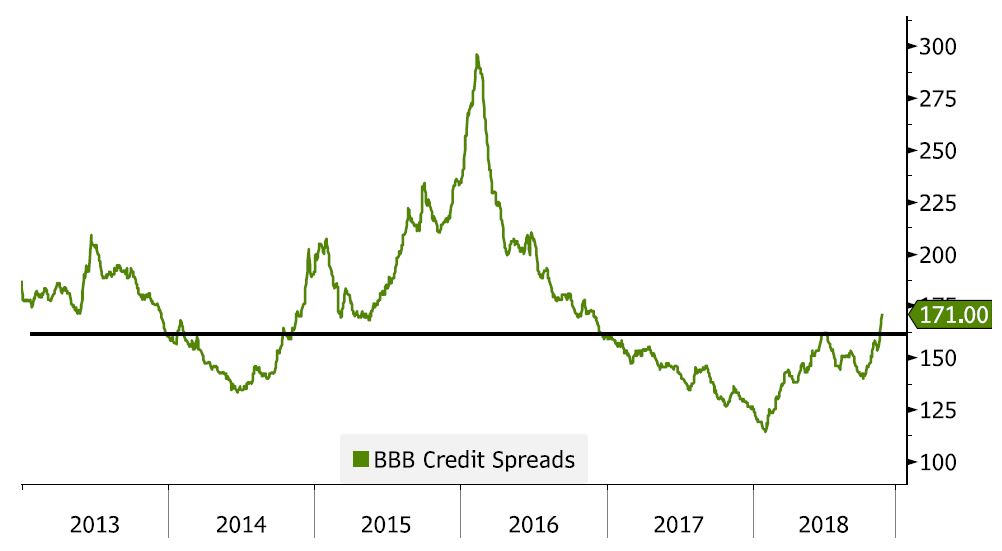

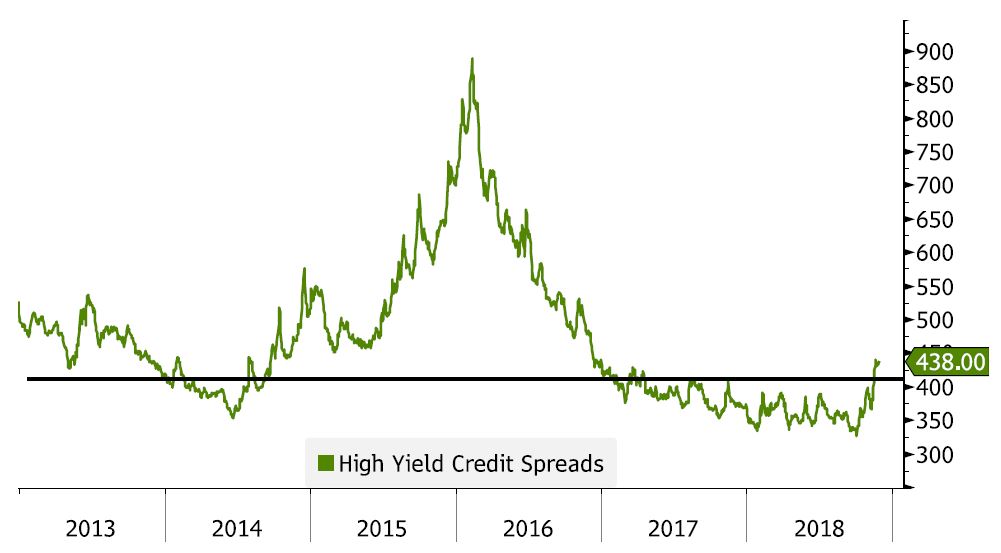

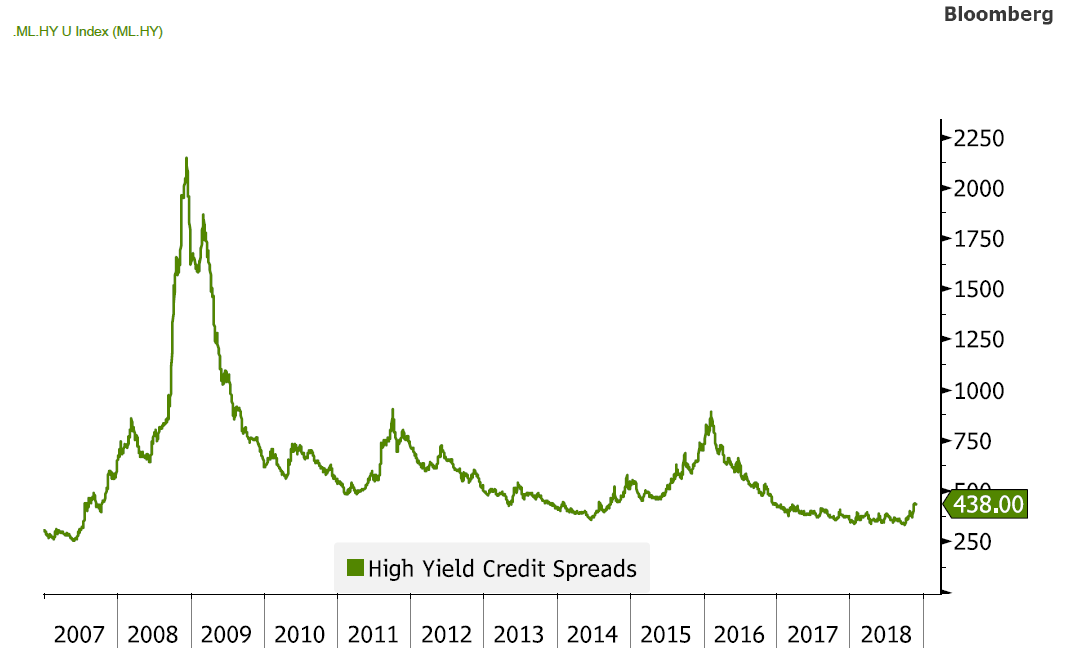

The other potentially very positive news, at least for income investors who play it safe in the near-term, is that credit spreads are beginning to widen out most decidedly. (Credit spreads represent the extra yield paid out by private sector debt issuers over and above the comparable maturity US government bond.)

BBB and High-Yield Credit Spreads 2013-2018

BBB and High-Yield Credit Spreads 2007-2018

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal as of 11/28/2018

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal as of 11/28/2018

Based on the above graphic, it’s inarguable that there is a new up-trend in place. What’s much more arguable is if it’s likely to lead to a reprise of the 2014 to early 2016 experience which saw credit spreads soar (though, of course, not to the same degree as during the global financial crisis when these exploded to Great Depression type levels).

It is Evergreen’s strong suspicion at this time that a much more severe up-move in spreads is probable as we move into 2019. Part of our reasoning rests on the aforementioned confluence of bad things happening simultaneously in America and around the world. For sure, there are still some considerable pockets of strength in the US but the earlier thesis expressed in prior chapters of Bubble 3.0—that America is likely to play catch-down with the rest of the world rather than it catching up to us—seems to be playing out.

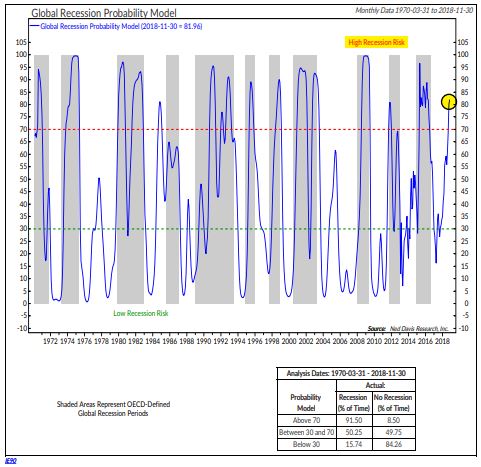

As you can see below, Ned Davis Research Global Recession Indicator is now very much in the danger zone. Further note that it is still heading in a northerly direction.

Source: Ned Davis Research as of 11/15/2018

Source: Ned Davis Research as of 11/15/2018

The last time it was this high was in late 2015/early 2016 when credit spreads were going vertical. What’s a bit ominous this go-around is that credit spreads have much further to rise to get in synch with this recession warning.

You may be wondering how this is good news. Well, if you are heavily exposed to the S&P 500 or high P/E tech stocks, it’s not. A significant rise in credit spreads has consistently been bad news for equities. By definition, it’s also tough on most longer-term corporate bonds since rising spreads almost always mean declining non-government debt prices (unless treasury yields are falling fast, which is definitely not the case—yet).

However, if you are an investor who holds hefty amounts of cash-equivalent type securities, credit spreads in blow-out mode is exactly what you want to see. For example, if we get a repeat of the 2014 -2016 episode, it will be possible to lock in yields of 6% or more—possibly even in double-digits—from investment grade securities (or those just a notch below) once fears of the next recession’s on-set become widespread. To be clear, in our view the credit spread eruption is in its early stages so it’s best to stay short-term and ultra-high quality for now.

But in the not-too-far-out-future, it’s going to be time to make some much different moves.

The potential sequential plan

In this section, it’s time to get right to the heart of the “upside from downside” thesis. To convey this, I will give our best guess on what the sequence of events is likely to be as the Fed continues to raise rates AND—very critically but mostly ignored—rapidly contract its massive balance sheet. As this tightening cycle nears a crescendo, it’s probable it will set off a powerful chain reaction that may rival what we saw 10 years ago.

First, though, the Fed’s balance sheet contraction is worth a brief digression. Per the foregoing, there’s been scant coverage of how meaningful this is but the November 26th, 2018, Barron’s had a telling statistic on why it is such a big deal. In an article “Will the Fed Back Down?” by Randall Forsyth, in his “Up and Down Wall Street” column (written for so many decades by the late and very great Alan Abelson*), he cited the work of Benn Stell and Benjamin Della Rocca. Their studies indicate that the Fed’s Quantitative Tightening, or QT (selling rather than buying government bonds, the opposite of the now-notorious QE), has been the equivalent of a 68 basis points (0.68%) series of rate hikes.

Moreover, if the Fed stays on pace with its now $50 billion per month sell-down program, that will equate to an additional 220 basis points (2.2%) of rate increases. Full stop! Let that sink in for a moment. If they are right (and I suspect they are in the ball park), that would mean nine conventional rate boosts (at ¼% per) PLUS another nearly 12 bumps. That equate to over 20 hikes! Yikes!!

You may remember the old Wall Street adage about “three steps and a stumble”. This means that when the Fed steps up rates three times, the stock market tends to trip. But how about 20 steps and a complete face-plant? As this newsletter has noted many times—and my old boss and hero Jamie Dimon has also emphasized--we’ve never gone through a double-tightening (rising Fed funds rates and a balance sheet shrinkage) before. No one knows how this is going to turn out but it’s a safe bet that it’s not going to be bullish for riskier assets.

Market veterans believe that it’s not the known problems that cause the whopper down moves but, rather, those that are off the radar of most investors. With the Fed’s rate hikes commanding so much press attention, its QT could be the real deal (and bull) killer. Illustrating how stealthy this is, when did you ever hear Donald Trump tweet against the Fed’s balance sheet dispositions? In other words, if the Fed wants to take some political heat off itself (and I’m not sure they do), it could raise in December, then announce it will only boost rates in the future if global markets calm down, and the US continues to grow at a decent clip, while maintaining its low-profile QT.

Thus, even if this is the last overt rate increase, there is a LOT more tightening coming down the pike unless the Fed also suspends QT which seems highly unlikely to me. All of Mr. Trump’s caterwauling against the Fed means that a double pause would look like total capitulation to political pressure, thereby greatly undermining the Fed’s vaunted independence, something it clearly holds dear.

Putting this all together, it seems to me that despite some inevitable against-the-grain rallies, this muy grande toro es terminado (i.e, stick a sword in the bull, he’s done). What we are likely to see in 2019 is credit spreads further escalating, more overleveraged borrowers (see GE) continuing to struggle, triggering a rising cycle of defaults, causing banks to clamp down on lending standards, putting further downward pressure on real estate values, and forcing the liquidation of record-high margin debt (along with the stock positions connected to it). In other words, the usual end of boom times-type domino effect. Unfortunately, this “value restoration process” is likely to be even more damaging due to the amount of debt (and its twin, credit) built up over the (too) long good years and the tight interconnectivity of almost everything these days.

On that latter point, these end-of-cycle events create problems as far away as India (where a banking crisis is already underway) which eventually feeds back to John Deere, that then lays off workers due to falling overseas orders, causing home prices to fall in Moline, Ill, and lenders to become nervous which is when they tighten credit. Eventually, this all feeds back into the corporate bond market which has the highest level of leverage in history and especially the trillion-dollar leveraged loan market, the latter having all the right stuff to become the next sub-prime mortgage fiasco.

As these stresses multiply and amplify each other, it will soon become time to come out of short-term treasuries and do something that very few will want to do: extend maturities. This will almost certainly be when short-term rates are just as high, or even higher, producing the usual objection that I’ve heard countless times over the last 39 ¾ years of my career: Why should I buy a 10-year treasury when I can get the same yield on a one-year treasury?

The answer is, of course, that as conditions become increasingly precarious (and recessionary), stocks will crater and the Fed will panic. It will begin cutting rates first and then soon, perhaps simultaneously, halt its QT process. At that point, long treasury yields will plunge.

Therefore, Evergreen’s first anticipated order of business is to move out of some of our cash equivalents into longer-maturity treasuries. This serves to lock in a decent yield but more importantly positions for capital gains as riskless rates plunge (falling rates causes rising bond prices), which consistently occurs after the gross stuff hits the fan.

If history is any guide, however, most longer-term medium grade (A/BBB-rated) corporate bonds are almost certain to hugely lag extended-maturity treasuries. This is part and parcel of the typical spread-widening process. Again, based on the staggering amounts of debt that have been piled on during this maniacal quest for higher returns up-cycle, we could easily surpass the 2016 peak (though we doubt spreads will blow out to 2008 levels). If so, this is when one of my old predictions might come true, namely, that in the next panic the Fed will seek to bring down credit spreads.

Some have derided this as a bad call since it hasn’t happened yet, but they missed the part about “in the next crisis”. Because the European Central Bank has already rolled out this tool, I believe the Fed will follow suit when the situation gets scary enough. In other words, it might sell more of its still multi-trillion dollar government bond and mortgage stash in order to fund the purchases of massive sums of A and BBB corporate debt (presumably, the higher rating levels won’t need the help). Frankly, I think this will be one of the best stabilization moves it can make under dire circumstances. If so, it could prevent the next bust from turning into the second coming of the Great Recession/Global Financial Crisis.

Regardless, it will be once spreads have zoomed up around the 2016 peak that it will be time to begin buying BBB- and even the better BB-rated bonds. As we’ve demonstrated multiple times in the past, it is possible to generate equity-like returns from corporate debt coming out of these convulsions—and with much higher income and much lower risk than with stocks. Any Fed intervention would only accelerate this outcome.

As credit spreads near a peak (never a precise point to determine in real-time and particularly in a panic), it will then be time to move close to fully invested in equities. As a reminder, presently Evergreen is around 50% of that for most equity portfolios. It’s been painful to be thusly oriented in recent years though it is noteworthy that we’ve now had two very difficult years (2015 and 2018) over the past four. Moreover, we still haven’t even had a “proper” (many would say “improper”) bear market in the S&P 500.

Supposedly, all good things come to those that wait, but this has been one whale of a waiting period. Yet, as these pages have often conveyed, that is likely to make the reward all the more lucrative—if we stick to our plan AND buy into the carnage. Undoubtedly, this will be very hard to do as we expect the intensity of negative news at that time to be extreme--just as it’s been excruciating to be cash-heavy during the late stage of this bull run. However, once again, our track record indicates we will be buyers when the computers and the passive funds are selling en masse.

To reiterate an oft-stated message, we expect to skew our purchases more internationally than we would normally due to the much better valuations overseas and the related multi-year lag those markets have had vis-a-vis the US. We further expect the midstream energy sector (MLPs and the related C-corps)—already so battered and high-yielding—will become even more so. (As a related side note, we anticipate a robust rally soon for this group giving us another chance to take profits and position for the next downside overreaction).

Obviously, we’ll adapt to conditions as they develop so some of the above sequence may change. But the essential message is that we strongly believe that the ONLY way to achieve high single-digit returns—much less double-digit—is to follow a strategy similar to the above. A standard balanced buy-and-hold approach simply isn’t going to cut it. In fact, it might be doing well just to break-even over the next five years.

Could we be wrong? On the timing, of course. Heck, we already have been! But unless every valuation method that has worked over time is wrong, US stocks are poised to seriously disappoint their legions of fans. And a 3% or 4% yield on treasury bonds will only soften the blow if they are just 30% or so of a portfolio.

At times like this, it’s going to require some radical measures to cope with all the years of market price distortion caused by the planet’s monetary mandarins, as Jim Grant calls them. In case you’ve forgotten, and I wouldn’t blame you if you had, the sub-title of this book-in-progress is: “How Central Banks Created the Next Financial Crisis” If I’m right, a lot of folks are going to be remembering that before too long.

*Over the years, in the hundreds of EVAs I’ve written, I’ve tried to at least faintly emulate the acerbic, but jaunty, writing style of Mr. Abelson. Now you know who to blame though, from what I’ve heard, he’s hard to reach these days.

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

Changes highlighted in bold.

LIKE *

* Some EVA readers have questioned why Evergreen has as many ‘Likes’ as it does in light of our concerns about severe overvaluation in most US stocks and growing evidence that Bubble 3.0 is deflating. Consequently, it’s important to point out that Evergreen has most of its clients at about one-half of their equity target.

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

* Credit spreads are the difference between non-government bond interest rates and treasury yields.

** Due to recent weakness, certain BB issues look attractive.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.