“We believe this is the last stand for our future and freedom. We'd rather die in the fight than slowly suffocate to death after we lose the fight.”

– Hong Kong protester

With so much happening politically, economically, and militarily around the globe, it can be challenging to grasp the full magnitude of any one incident. News seems to come and go almost instantly, quickly leaving a once-pressing subject in the rear-view for a flashy new headline. Former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has even quipped that “it’s not a 24-hour news cycle, it’s a 60-second news cycle now.” Given that the nature of news today is fleeting, it becomes even more remarkable when a topic has staying power over a long period of time.

Such is the case with the mass demonstrations in Hong Kong which reached a new escalation this week after over 250 days of protests. For those that have tuned out the noise until now, the protests started in March when the Hong Kong government introduced a bill that would have let local authorities detain and extradite criminal fugitives to territories that Hong Kong does not currently have extradition agreements with (including Taiwan and mainland China). As the protests have progressed, demonstrations and demands have grown louder, blossoming into a broader movement in opposition to a semi-autonomous government (from Beijing) that has resisted calls for democratic reform.

On Tuesday, the U.S. Senate showed support for the Hong Kong democracy protesters, unanimously passing a bill that would amend the United States-Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992. In its original form, the Act outlines an agreement for the U.S. to treat Hong Kong differently from mainland China in terms of trade and commerce. The policy pivot comes in defiance of the Chinese government, who has urged the U.S. to stay out of Hong Kong affairs, and could very well threaten an elusive trade agreement between two of the world’s most dominant trading powers.

This week’s newsletter comes from Evergreen’s partner Louis-Vincent Gave who has a distinct vantage, having lived in Hong Kong for two decades. Louis’ article, which was originally published on November 12th, provides musings on three relevant questions:

Given the United States’ support of Hong Kong protesters this week, it is probable that the impact of these demonstrations will extend beyond the South China Sea – as Wednesday’s hiccup in US markets suggested. The extent to which the temporary trade truce between the US and China begins to unravel is still very much an open question, but tensions are undoubtedly beginning to boil again which will likely carry over into what has historically been the most wonderful time of the year for markets.

In Evergreen’s view, we believe Singapore might be a long-term winner from Hong Kong’s potential demotion as the leading Asian financial center. History is clear that there are always beneficiaries in the wake of true crises. For Hong Kong, this is the most serious crisis since the handover from the UK to China back in 1997.

When writing Q&A On The Hong Kong Dollar Peg back in May, there was no inkling that trust between the police and much of Hong Kong’s population would fully break down. Today, there is a parallel with the 1992 riots in Los Angeles, for as in LA after Rodney King’s beating, Hong Kongers are saying: “We don’t trust the police to do the right thing, or even speak the truth”. This situation does, however, remind me of a quote from Gone With the Wind when Rhett Butler turns to Scarlett O’Hara and says: “I’m going to be a rich man when this war is over, Scarlett, because I was farsighted—pardon me, mercenary. I told you once before that there were two times for making big money, one in the upbuilding of a country and the other in its destruction. Slow money on the upbuilding, fast money in the crack-up.”

Hong Kong’s situation is hardly comparable to the US civil war (thank God for small mercies) but there are wannabe Rhett Butlers out there. And bearishness on Hong Kong has typically been expressed in two ways: (i) bets against the currency peg, and/or (ii) shorting property developers. And for proponents of both trades, the money to be made in the crack-up isn’t coming fast enough. In fact, in recent meetings a recurrent question has been the resilience of both the linked exchange rate system and stock values. Yet, in light of the November 11th -2.6% fall in the Hang Seng Index, it is fair to ask if the market is finally shifting its view. Consider the following:

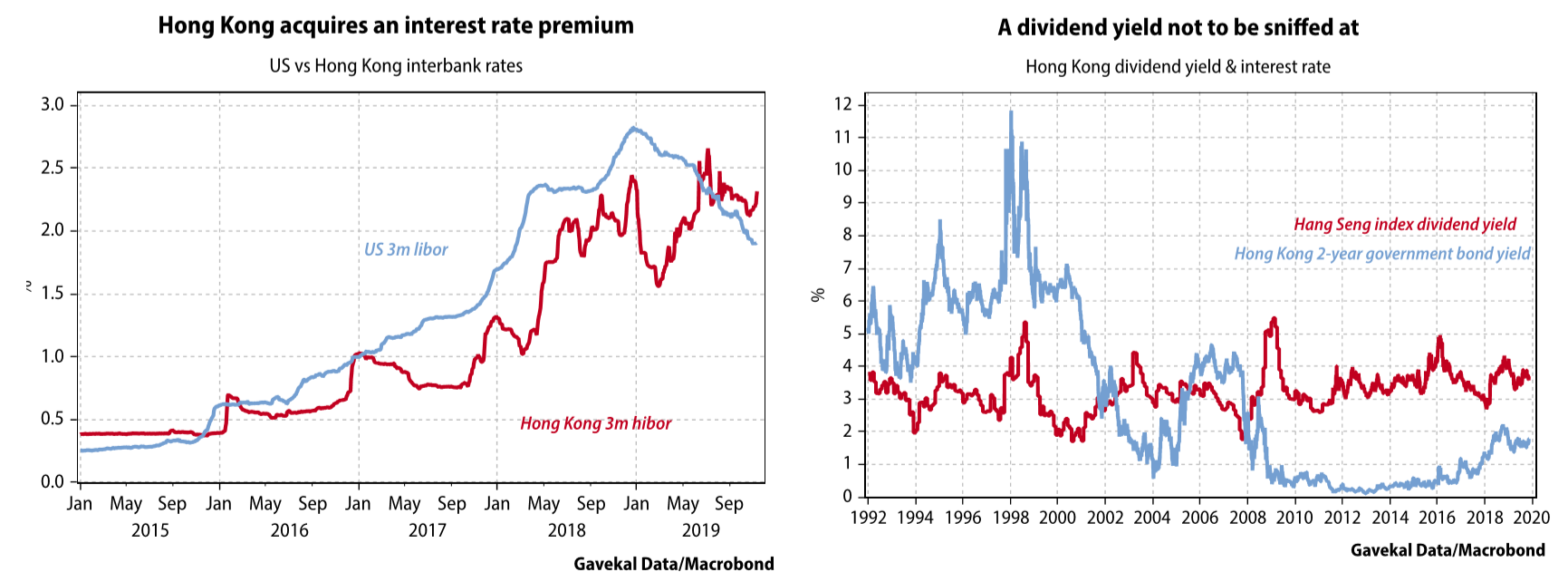

Why hasn’t the Hong Kong dollar peg broken down? After all, in the last six months pretty much everything that could go wrong for Hong Kong has done so. Perhaps the more interesting question is why, in spite of capital outflows, have local interest rates remained so stable? The idea of the peg is that as capital leaves Hong Kong, interest rates should rise relative to US rates. It is this rise that should attract capital back, and so cause the Hong Kong dollar to strengthen. During the 1997-98 Asian Crisis, the HIBOR* rate soared, sparking an eventual -70% fall in property prices and a -20% decline in wages. In this year’s crisis, however, local rates have remained fairly steady.

Still, for the first time since 2016, local interest rates have risen meaningfully above US rates (40bp** as shown in the left-hand chart below). This means that the short Hong Kong dollar trade—which in the spring offered a positive carry trade of 60-100bp—now costs 40bp to run. This is occurring at a time when the Federal Reserve has moved from shrinking its balance sheet and raising interest rates to expanding its balance sheet and cutting rates. i.e. the Fed has stopped shrinking the supply of US dollars (bullish dollar) to aggressively expanding the supply of US dollars (bearish dollar).

Why have Hong Kong stocks, especially property stocks, been so resilient? It is fairly obvious that Hong Kong real estate prices are downright stupid compared to incomes, population growth or comparable cities. This situation persists because the Hong Kong government continues to constrain the supply of development land. Depending on one’s perspective, this can be variously explained by (i) the government preferring to fund itself with land sales rather than taxes (without representation, no taxation), ii) a tycoon oligarchy is, in fact, running policy, or (iii) the government not wanting to upset a highly levered middle class, even if that means sacrificing the working class.

Whatever the reasons for the bone-headed supply restrictions, it seems fairly clear that such policies must now end. The supply of new homes will have to rise, but this will happen in an overall economy that is likely to be rendered moribund, even if the riots die down (tourism from China is not likely to rise any time soon given the anti-Mainland venting of recent months).

But if this is the case, why haven’t Hong Kong stocks been hit harder? So far this year MSCI Hong Kong has underperformed MSCI World by about -10pp***. This isn’t ideal, but pales in comparison to the face-plants in markets like Chile and Lebanon, which have also seen political strife. What I’ve learned from two decades of living in Hong Kong is that the currency rate is never the variable of adjustment for cycles, but asset prices almost always are. This time, however, asset prices (whether equity or real estate prices) have yet to register any meaningful pullback. Possible explanations for this include:

An interesting parallel can be found in Australian banks, which at the start of this decade were a favorite short of hedge funds: real estate prices in Australia were falling, the commodity cycle looked to have peaked, leverage ratios were high and the regulator was coming after them. Yet despite these problems, Australian banks offered a high dividend yield, which made them a favorite for retail investors (it also made shorting them expensive). As a result, the trade tended to be disappointing (at least in Australian dollar terms).

This isn’t to say that Hong Kong is the obvious place to deploy the marginal dollar of investment capital. While Hong Kong equities usually do well when the Fed eases and the US dollar rolls over, recent events will negatively impact domestic capital spending, real estate prices and tourism. Yet at the same time, an adjustment through the exchange rate remains unlikely given that interest rates remain low and local assets are mostly in local hands.

*HIBOR stands for Hong Kong Interbank Offered Rate and is the benchmark interest rate, stated in Hong Kong dollars, for lending between banks within the Hong Kong market

**bp stands for basis points; a single bp represents one hundredth of one percent

*** pp stands for percentage points and is a unit of one percent

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.