“Every decision on trade…will be made to benefit American workers and American families. We must protect our borders from the ravages of other countries making our products, stealing our companies, and destroying our jobs. Protection will lead to great prosperity and strength.”

–DONALD TRUMP

“We should keep on going along the path of globalization. Globalization is good... when trade stops, war comes.”

–JACK MA, founder of Alibaba

Nearly two years after the US launched an investigation into Chinese trade policies, it seems as if the battle for pole position of the global economy has reached an inflection point. Aside from the tariffs, the threats of tariffs and, yes, the threats of even more tariffs, that have continued back-and-forth between the two countries like a painfully long ping-pong match, the Trump administration upped the ante last Friday by blacklisting Huawei. As a result, US chipmakers, including Intel, Qualcomm, Xilinx and Broadcom, have suspended supplying Huawei with semiconductors – a devastating blow to the Chinese telco.

What’s still unclear is just how far each country will go in this war of attrition. With no end – or deal – in clear sight, the jury is out on how this story will conclude. One historical parallel is the War of 1812, which was birthed out of a trade war between Britain and France and fought partially as a trade war between Britain and the US. In that war, the US wanted to reduce its dependence on Britain, which was seen as a powerful economic and military threat. Sound at all familiar?

While all hopes – and expectations – are that the current clash won’t escalate past the point of trade, the more pressing threat is that the ongoing spat will upend nearly ten years of economic expansion. However, those keenly focused on the idea that the US-China trade war will be the thing that sparks the next global economic meltdown, may want to consider diverting their attention to an unseen trouble lurking in the European banking system. But more on that below…

TRUMP'S TRADE WAR CALCULUS

By Arthur Kroeber

Keeping track of all the pieces of the US-China confrontation has become a full-time job. But the chaos and uncertainty of the past couple of weeks has begun to resolve itself into fairly clear patterns, even if the outcomes remain in doubt. Three main conclusions emerge from last week’s activity. First, a trade deal now looks unlikely to happen until much later this year, if at all. Second, Donald Trump’s administration is obviously trying to turn down the volume on other trade conflicts so that it can focus on China; but there is still material risk that Europe gets hit with tariffs or quotas on cars and car parts at the end of the year. And third, the US-China technology war is intensifying (with Huawei now the main target) and will continue to do so, regardless of the ultimate result of trade talks.

The main thing that has changed in the trade negotiations is the political dynamic. Until two weeks ago, it seemed that Presidents Trump and Xi Jinping, for their different reasons, both had strong incentives to cut a deal. Now the reverse seems the case.

Trump evidently feels his political standing benefits more from taking a tough posture against China than by striking a deal that will be attacked both by the hardliners in his administration and by Democrats in Congress. A strong US economy and an outperforming US stock market so far give him comfort that this position is a low-cost one. Xi, meanwhile, cannot possibly sign a deal that seems like a total capitulation to a long list of American demands, with no benefit to China. And China’s economy is strong enough that he might think he can risk a no-deal outcome.

With both sides painted into corners, there is little chance of a deal before the June 28-29 G20 meeting in Japan, which both Xi and Trump are expected to attend. This can only occur if Trump changes his mind, decides he wants a trade deal trophy from the meeting, and orders his negotiators to patch up an agreement with enough tariff relief to make it palatable to Beijing. Trump is mercurial, so this is not impossible. But it is unlikely.

Assuming the G20 comes and goes without a deal, there are two possible paths. One is that the two sides resume negotiations and try to resurrect an agreement before the economic and market damage of the trade frictions becomes too acute, sometime later this year. The other is that they conclude the gap is unbridgeable, and the existing US tariffs become permanent, along perhaps with additional levies on the roughly US$300bn of imports from China that remain untariffed.

Which of these two courses gets followed depends largely on the direction of the US economy and markets. So long as US markets hold up and the economic cost of the trade war to Trump’s supporters seems manageable, he will see little downside to a hardline strategy.

This logic also applies when handicapping the risk of auto tariffs on Japan and Europe. One reason US markets were so sanguine last week was that it was clear that Trump was scaling down conflicts in other areas, at least in part to ensure room for keeping up the pressure on China.

The auto tariffs on the EU and Japan—apparently recommended by the Commerce Department’s Section 232 investigation of the supposed impact on national security of car imports—were deferred for up to six months. Aluminum and steel tariffs on Canada and Mexico were lifted, paving the way for ratification of the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement that will replace Nafta. And Trump also made clear that, despite moving an aircraft carrier into the Straits of Hormuz, he has no interest in escalating the conflict with Iran (although in a subsequent tweet on Sunday he sounded a more bellicose note).

But as far as auto tariffs are concerned, the risk is still alive, even if on a longer time horizon. The most consistent error people have made in analyzing Trump is in underestimating his commitment to protectionism, and his belief that protectionism is an end in itself, not just a negotiating tool. Trump evolved these ideas three decades ago and has never wavered. In 2016 he campaigned on withdrawing from the TransPacific Partnership, renegotiating Nafta, and imposing a big tariff on Chinese imports. He has delivered on all three.

Moreover, Trump’s animus on trade started with Japan and has long included Germany, for which he seems to harbor greater hostility than towards China (and while he boasts of a great relationship with Xi, he has never shown warmth to Angela Merkel). His proclamation on the auto issue makes clear that he wants a fight, with the aim of reducing imports of cars and parts either by tariff or by quota. Given the intensity of his views and his track record of doing what he says when it comes to protectionism, there is every chance that car imports could be hit with sanctions, so long as economic and market conditions put the US in an apparently strong position.

Finally, we should prepare for an intensification of Washington’s ongoing efforts to stem the flow of technology from the US to China by investment restrictions, export controls, and limits on visas for tech-oriented students and workers. This agenda is driven by hardliners in the US security establishment, not Trump, but he is doing nothing to rein them in.

This war is being waged on many fronts, but the biggest one at the moment is Huawei, which was put on a US export-control list last week. I am skeptical that this move has anything to do with increasing American leverage in the trade talks. The US already has plenty of leverage via tariffs, and threatening to destroy one of China’s national champion firms will if anything make China less willing to come to the table on trade.

A better explanation is that many in the US government have long felt Huawei to be a security risk because of its allegedly tight links to the People’s Liberation Army and Chinese intelligence services, and now believe this risk to be unacceptably high given Huawei’s leadership in 5G network technology. They therefore want to cripple the company, or at least prevent it from installing networks in allied or friendly countries. So long as the trade talks seemed headed for success, action against Huawei was put on hold, to avoid torpedoing a deal. But with the trade deal now in ruins, there was an opening for an aggressive move.

If the US cuts off all exports of semiconductors and components to Huawei the company most likely will not survive. This outcome may be too costly given that Huawei is a big revenue-spinner for US hardware firms, and its destruction could retard the rollout of 5G. But Washington will surely push hard to subject it to vastly tighter constraints, and will strongly resist any effort to link what it considers a core national security issue with the trade negotiations.

THE TROUBLE UNSEEN

By Charles Gave

The world and its dog are suddenly worried that the growing US-China trade war may be the event that sparks the next panic, and ends this economic expansion. Might I suggest that the looming iceberg that could yet sink the good ship Global Growth may not lie in the obvious spot where spy glasses are focused? Could I have everyone’s attention just for a moment and suggest that the real menace may still lie in the European banking system?

Central bankers are first and foremost bankers, and their main job is to prevent a systemic meltdown similar to those seen in the 1930s and in 2008, when the Federal Reserve foolishly let Lehman Brothers fail. It is also clear that the euro’s creation in 1999 was a grave policy error and banks in the single currency area are only alive due to life support from their central bank. In my view, the next panic will come not due to the fight unfolding between China and the US, but from European lenders plumbing new depths.

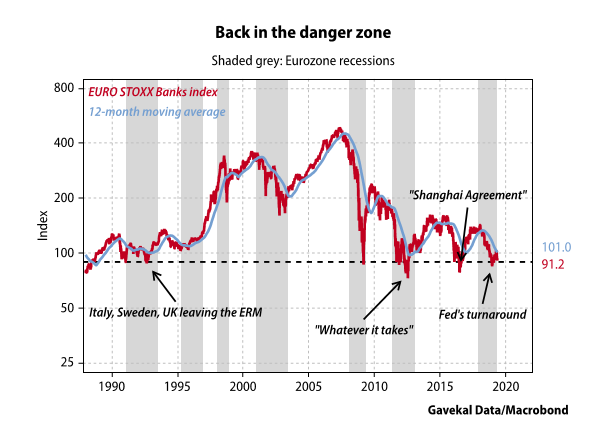

This argument is best made using the chart below. It shows a remarkably consistent floor for Europe’s main banking index. I have noted before the long history of central banks intervening when this index falls to about 90. Most recently, this was seen in the dark days of last December. My point today is that the benchmark is slipping, almost unnoticed, back towards the danger zone, and the threat posed means there must be a massive intervention, or a bust.

Consider some past flirtations with disaster. In 1992, as Germany reunited, the Bundesbank responded to the generously priced merging of the Eastern ostmark and Western deutschemark by driving up real interest rates to very high levels. This led Sweden, the UK and Italy to exit the fixed exchange rate mechanism that preceded the euro’s creation. As this crisis culminated, the European banks equity benchmark fell from 120 to 90. In the ensuing decade, things calmed down and the index more than quadrupled.

Roll forward to the global crisis of 2008. In the course of a year the same index fell from about 450 to about 90. On that occasion, the relief valve was the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing program and China massively expanding credit creation. European banks again dutifully rebounded smartly.

A couple of years later, it became clear that Greece was bankrupt and the eurocrisis started in earnest. The European banks equity index plunged from 223 to 77, and the only thing averting a full-scale collapse was the promise by the European Central Bank’s new chief, Mario Draghi, to do “whatever it takes” to save the system. In the aftermath, the index bounced to 154.

Fast forward to 2015 as China’s economy swooned and a surprise renminbi “devaluation” sparked fears of a global deflationary bust. European banks broke below the 90 level, only to bounce as a currency “agreement” was put in place at the February 2016 meeting of the G20 in Shanghai, and the ECB said it would buy European corporate bonds. You know what happened next!

That brings us to December 2018, when the European banking index had fallen from 133 to 90. This time the turnaround was sparked by the Fed dramatically reversing its policy and the banks benchmark duly rebounded to 110. Today, however, we are back in the red zone with the index at 93.

The thing to note is that the recovery from each sell-off seems to be getting shorter and smaller. What this says is that the world’s central banks are starting to run out of ammunition. If the index duly breaks below 90 in the coming months, as a new recession hits Europe, all bets really would be off.

If I could only use one chart to monitor world financial markets, this would be it, although I may add the share prices of Italy’s UniCredit and Germany’s Deutsche Bank, as they look especially sick. I would also keep an eye on Turkey as its central bank is obviously running out of foreign exchange reserves and a lot of loans to Turkish entities were made by European banks.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.