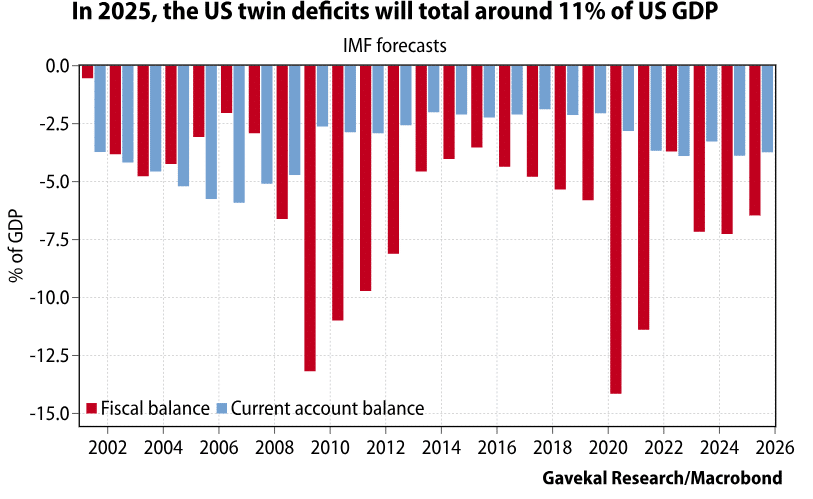

The US runs twin deficits of 10-11% of GDP; roughly 6.5% of GDP on the budget deficit, and almost 4% on the current account deficit.

Conceptually, that is a lot of excess US dollars “floating” around in the global system. So, what can the foreigners on the other side of the very large US current account deficit do with all the US dollars they earn?

There is little doubt that, for the past 10 years or so until the start of 2025, the third scenario prevailed. The US consumer was pushing a lot of dollars abroad, but these dollars quickly made their way back to the US via private equity funds, private credit funds, leveraged bets on Nasdaq or crypto investments.

It is also obvious by now that the Trump administration has shifted the narrative. Re-investing excess dollars into the US is no longer a slam dunk for foreigners. Firstly, because of the uncertainty surrounding policy. Secondly, because it increasingly seems that Trump’s promises to get government spending under control were as empty as a church on a weekday. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, because the one intellectual thread linking all of the various Trump measures is the idea that “foreigners will pay”.

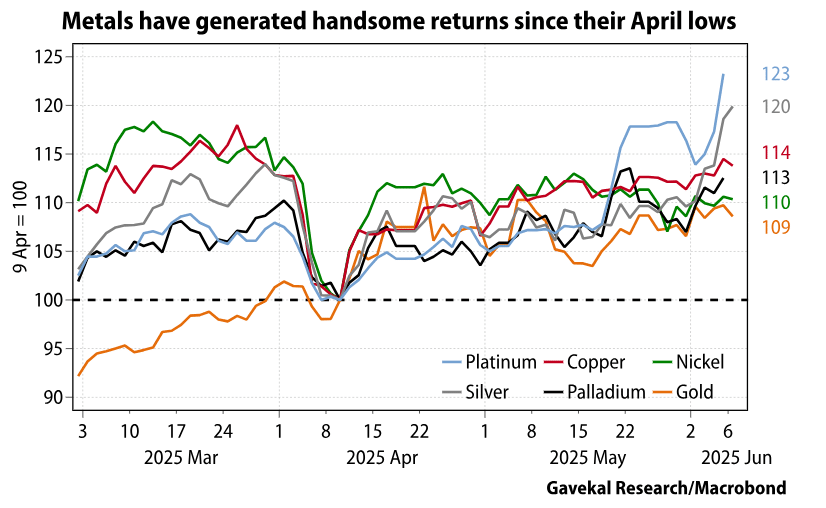

As a result, in recent months foreign exchange markets have shifted from the third scenario, in which foreigners willingly reinvest in the US, to the first scenario, in which they start to accumulate more inventories and more commodities, and the US dollar becomes a hot potato quickly passed from hand to hand. Since the lows that followed “liberation day,” it is no longer just gold that is doing very well among metals. Suddenly, silver is making new all-time highs, while copper, platinum, palladium and nickel are all outperforming gold.

Still, from recent conversations with clients, it feels as if the world’s large institutional investors have not yet fully embraced the second scenario by selling US dollars to invest domestically. This is not out of any sense of loyalty to the US. More often than not, it is because of a lack of opportunity in home markets, which often are too small for Scandinavian or Canadian pension funds, German insurance companies, or Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds.

This brings me to the important question at hand: now that most of the world’s largest pension funds want to buy more domestically and less in the US—an understandable reaction in times of greater uncertainty—will local governments step up to the plate and provide assets that pension funds will willingly buy? And no, this doesn’t mean lame government bonds whose proceeds just go into kicking the welfare-state can a bit further down the road. It means genuinely attractive assets.

Cometh the hour, cometh the former Goldman banker? In Canada, the nepo-baby drama teacher has now been replaced by Mark Carney, who has an unusual window of opportunity to unleash spending on the infrastructure—pipelines to the coast, LNG export terminals—needed for Canada to reduce its dependence on the US; spending that Canada’s massive pension funds would be delighted to fund.

In Germany, the new chancellor is a former corporate lawyer who could structure infrastructure bonds to upgrade Germany’s electricity grid in his sleep. And in the Middle East, plans are already in train for massive AI data centers powered by the region’s abundance of cheap energy.

All this to say that for now, the market remains skeptical that large capital allocators will ever abandon the US. Sure, they may have started to recycle less capital into the US, and at the margin this is weighing on the US dollar. And sure, some money may be starting to go into commodity stockpiling. But we have yet to witness an exodus of foreign investors from the US. And this is in spite of the US newsflow, which from a foreign investor’s point of view has been a lot less than enticing.

It therefore seems that it will take a much greater deterioration in the US newsflow to trigger a full-scale exodus. A US recession? The threat of capital controls? Greater taxes on foreign capital? Or alternatively, perhaps foreign policymakers will step up to the plate, creating domestic assets that pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds actually want to buy.

Today, everyone is focused on the first possibility. But might the probability of the second be greater? In the meantime, it seems that the marginal excess foreign dollar is now more likely to head into commodities than into the Nasdaq, even as domestic US dollars remain wedded to US tech stocks.

DISCLOSURE: Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.