“Right now, the Fed would love a little more inflation, which has persistently fallen short of its 2% target. But what if it’s headed well past 2%? The Fed knows what to do, because it’s done it before: raise rates and cool the economy.”

– The Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip on 4/23/20

“History clearly indicates that there will be some limit to the market’s willingness to tolerate increased deficits and rising public sector debt ratios, particularly when the latter (even excluding off balance sheet items), are already at unprecedented levels.”

– Bill White, former chief economist of the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), considered to be the central banker for the planet’s central banks

“The more we look to over-optimize everything (supply chains, balance sheets, portfolios) and not keep any safety cushions because the ‘governments and central banks’ have our backs, the more fragile we make the system.”

– Louis-Vincent Gave

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

At the end of 2017, we initiated a special-edition EVA series with excerpts from David Hay’s upcoming book titled “Bubble 3.0: How Central Banks Created the Next Financial Crisis.” If you are just joining us at the end of this series, which will soon culminate in a full-length publication, please read the prior installments in the series here:

Last week, Dave kicked off Part I of his final chapter from “Bubble 3.0”. This week, David puts the finishing touches on his long-running thesis and finally unveils the Fed’s ultimate “End Game”.

This book has clearly been an indictment of Fed policies over the last twenty-five years. Some will no doubt think it has been unfair, particularly when, like now, the Fed is in its fire brigade mode. In other words, its popularity tends to soar during times of crisis that cause it to use its limitless money manufacturing machine to save the day.

As we have repeatedly seen, it doesn’t take much of an emergency to catalyze yet another Fed monetary deluge. Currently, however, this is a five-alarm fire and the Fed is right to be fire-hosing the conflagration with its endless supply of liquidity. Yet, this is not to excuse its role in starting the inferno, a point I attempted to make in “End Game (Part 1)”. To requote Jim Grant, the Fed has repeatedly played both arsonist and fire-fighter.

In order to directly confront the many who disagree with my take on our seemingly all-knowing and all-powerful central bank, consider this reality: each of the Fed’s rescue efforts in the wake of Bubbles 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 have become larger and further outside of its original charter. A cynic might say it has become increasingly desperate.

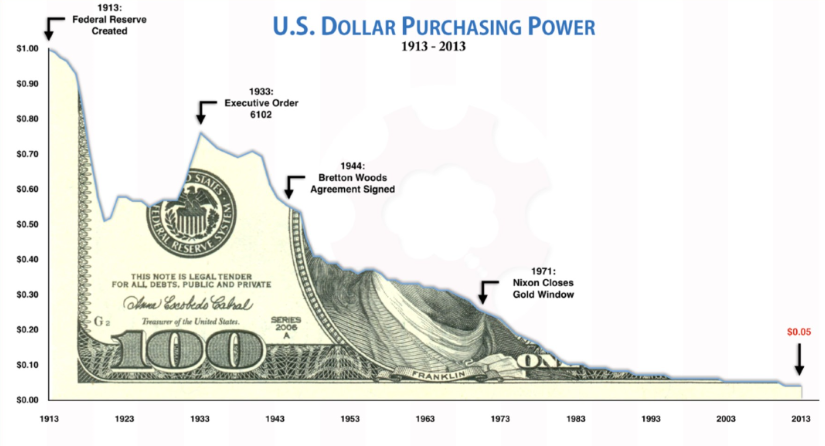

But let me make an even more damning and irrefutable assertion: the Fed has been, for most of its existence, a deplorable protector of our nation’s currency. If being a credible defender of the US dollar involves protecting its purchasing power, there is simply no other conclusion than the Fed has failed the country miserably.

As earlier EVAs have conveyed, the US dollar admirably retained its purchasing power from the early days of America’s founding until WWI when the Fed came into being. There was one high-inflation period during the Civil War but in the following decades deflation was more common. There were also numerous panics and busts in the years from 1865 to 1914 (when WWI broke out in Europe) but it was also a time of strong economic growth. In fact, it was in these years that the Gilded Age occurred, and the country’s first great fortunes were created such as those of the Rockefellers, the Carnegies and the Mellons.

Unquestionably, the first 130 years of our country’s existence were tumultuous. The spectacular economic growth seen in that century-and-a-third was erratic and typically inequitably distributed. It was a time of repeated booms and busts with the last of the latter—the panic of 1907—producing a groundswell of support to create a central bank that would smooth out severe economic ups and downs.

Consequently, at a seaside resort on Jekyll Island, Georgia in late 1910, the plans were laid for what a few years later would become America’s Federal Reserve Bank. It was a momentous development, to say the least (some might say “monstrous”, but I believe that is too harsh).

For the first twenty years of its existence, the Fed didn’t do much at all; however, during the late 1920s it did accidently provide a sneak preview of its behavior some 80 years later. The Roaring Twenties gave birth to the first great bubble the Fed faced since its formation—the epic stock market mania that famously crashed in October, 1929. So catastrophic was this event that it scarred the entire planet for the following decade and arguably set the wheels in motion for WWII.

The Fed’s next great challenge was after the crash as America and the world entered the Great Depression. Staggering sums had been wiped out in the stock market plunge and then the banking system began to collapse in an era when there was no deposit insurance. By 1932, there was very little money left to be spent or invested. The Fed allowed the money supply to collapse in the early 1930s, an error so grievous that even left- and right-wing economists agree on its enormity. And, thus, it had two chances to prevent a calamity yet it whiffed both times.

For the next 40 years or so, the Fed returned once again to the periphery, other than to help finance WWII with its first debt monetization program (where it used money it created to buy government bonds). It then employed various tools to keep rates suppressed after the war was over, allowing the US government to use gradually rising inflation to lower the real value of the unprecedented sums it borrowed to defeat the Axis powers.

During the 1950s, characterized by a jagged but powerful recovery after WWII, one of the great Fed chairmen took the helm - William McChesney Martin. It was he who coined the now iconic phrase: “it’s the Fed’s job to take away the punch bowl just as the party gets going”.

Source: Wall Street Journal

In other words, once the economy was roaring, stocks were booming, and everyone was feeling giddy, the Fed’s job was to take away the hooch of easy money. It needed to act in what economists call a “counter-cyclical” way. That one simple concept gets to the core of how a responsible central bank should operate, in addition to the other necessary counter-cyclical action of infusing as much money as necessary to deal with panics and crashes. The first part of this ideal mission statement gets to the heart of what I believe the Fed has failed to do over the last quarter-century.

To reiterate a point made in “End Game” Part 1, citing the ever-astute Mike O’Rourke, the Fed has become asymmetrical. In plain English, this means that it excels at money creation to fight busts but it has forgotten Bill Martin’s admonition about taking the punch bowl away just as the party gets going. The emphasis was added to underscore the concept that the joy-juice removal needs to happen early, not after everyone is falling-down drunk. At that point, the damage has been done.

Bill Martin’s successor at the Fed, Arthur Burns, ignored this golden rule of central bankers. He was harassed by a GOP president obsessed with getting re-elected (sound familiar?). In allowing easy monetary conditions to persist for too long, Mr. Burns helped accelerate the inflationary fiasco of the 1970s. After a brief stint by another ineffectual Fed-head, the next great Fed Chairman, the recently deceased Paul Volcker, was given the keys to the Mariner Eccles building. As most EVA readers know, Mr. Volcker did what was popularly thought to be impossible: he crushed inflation. He also triggered a brutal recession which some hold against him to this day, typically economists and politicians who support perma-easy money policies, inflation be damned (this is a key point that I’m definitely going to come back to later in this closing chapter). Others would argue, myself included, that Mr. Volcker set the stage for the remarkable performance of the US economy from 1982 through 1999.

Mr. Volcker resigned in 1987, reportedly due to his anger at being pressured into easy money policies by the Reagan Administration. His successor was Alan Greenspan who would “reign” for eighteen years and preside over most of the golden years of the ‘80s and ‘90s. His reputation would become so lustrous that he was dubbed “the Maestro” by an adoring media. Unfortunately for his legacy, Mr. Greenspan chose to stay on the job a bit too long. The worst bear market of the post-WWII era happened on his watch, triggered by the 2000 to 2002 tech stock collapse. The internet frenzy of the late 1990s was, of course, Bubble 1.0, as mentioned in numerous past EVAs.

To further tarnish his once impeccable curriculum vitae (CV), Mr. Greenspan was also instrumental in the inflation of Bubble 2.0, the great housing frenzy that characterized the first decade of this century/millennium. Without a doubt, Mr. Greenspan ignored Bill Martin’s fundamental rule of central banking. This is despite the fact that he did raise rates in the late 1990s. Any credit he gets for that was undercut because he cut rates during a relatively minor market setback in 1998. Worse, he left them reduced as the tech bubble swelled to immense proportions through the first half of 1999. Additionally, in the second half of that year, he injected huge sums into the US financial system due to Y2K fears.

Then, bizarrely, as the absurdly over-owned tech sector vaporized, the Maestro kept raising rates before doing a radical mid-course adjustment, slashing the fed funds rate down to the lowest seen since the Great Depression (outside of a brief stretch in the 1950s). As mentioned in “End Game (Part I)", Mr. Greenspan kept rates at panic levels even as the economy was recovering from the shock of 9/11 and Gulf War II. This catalyzed housing to enter a full-fledged bubble. But before that explosively burst, he had the good sense to retire and leave the next bust on the resumé of his successor, Ben Bernanke. (However, many learned sources correctly blamed him for much of the resulting cataclysm.) Which leads us to the current decade and the ultimate end game I see heading our way…

It was Mr. Bernanke who came up with the idea of Quantitative Easings (QEs) once he’d cut interest rates so close to zero that any further cuts would have been ineffectual, if not counterproductive. (We have seen ample evidence of the latter in Europe where negative interest rates have been in place for years and have devastated its banking system.) Frankly, I was in favor of QE1 though, as expressed at the time and in this book, I’d hoped it would have targeted corporate bonds and non-government mortgages. But subsequent QEs did precious little to help the economy and they created extreme asset price inflation, aka, bubbles. And, hopefully, one takeaway all readers will get from this book, is that EVERY bubble meets its pin prick at some point. The bigger and longer the bubble, the more painful the aftershocks tend to be.

So, now we are on the fifth iteration of QE (I’m not giving the Fed a pass on QE 4 per last week’s EVA, which was launched due to turmoil in the overnight bank repo market*). As noted in that issue, QE 5 is almost certain to be bigger than QEs 1 through 4 combined.

Is the Fed wrong to be doing these things under today’s panic-stricken conditions? It may shock you to read this, but I don’t think so. In my opinion, it doesn’t have any other choice, though I would also argue it should never have come this—such radical measures could have been avoided by diligently following Bill Martin’s golden rule. Moreover, I think recent market action confirms a point I’ve tried to make for years: if the Fed had targeted the most at-risk and problematic areas of the financial markets in the fall of 2008, right when that meltdown began, we would likely have avoided most of the carnage that came in its wake. This, in turn, caused the worst economic downturn since the 1930s (again, until this spring, that is).

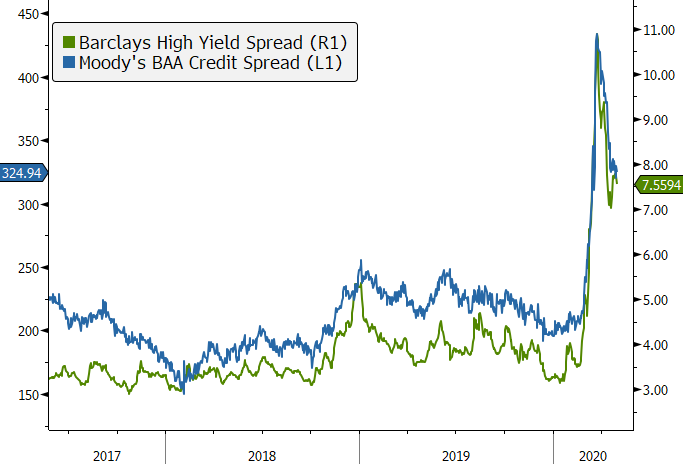

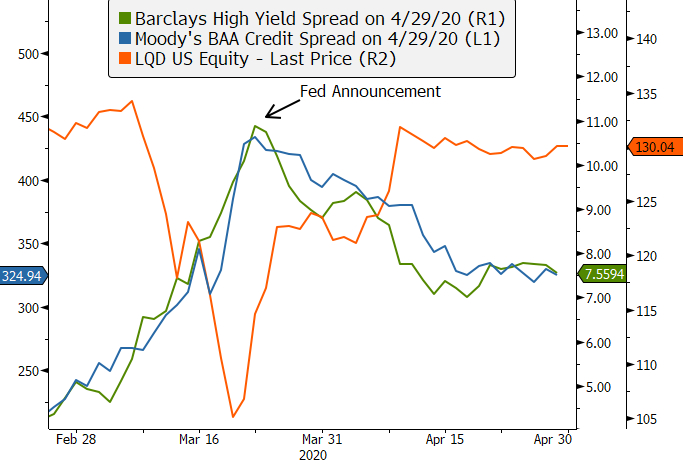

The proof is, I think, in the extraordinary rally both stocks and corporate bonds have had since late March when the Fed fulfilled my long and much-derided prediction that it would seek to bring credit spreads* down in the next crisis. At one point last month, the investment-grade corporate bond ETF (LQD) had swooned by 20%. That is a shocking decline for a high-grade bond vehicle, especially at a time when government bond yields were collapsing (driving up the value of Treasury bonds). This meant credit spreads were exploding, as you can see from the following chart.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

But note what has happened to both the ETF price and credit spreads since the Fed trained its big guns on this market. By the way, it’s not a coincidence stocks have rallied hard since then because dramatically falling credit spreads have always trigger a powerful up-move in equities.

*Credit spreads represent the difference between the interest rate on government vs corporate bonds.

LQD (orange line) is the Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

In my view, it’s nearly inarguable that this rapid and unprecedented move by the Fed is why we have the odd situation that was described by Schwab’s Liz Ann Sonders as “… a monster mash-up of the Great Depression in size, the crash of 1987 in speed, and a 9/11 attack in terms of fear” and yet a stock market that is technically back in a new bull market! No matter how long you’ve been in the financial game, this is like nothing we’ve ever seen before. But in my mind, it is proof-positive of the power of the Fed’s printing press, particularly when applied to something as meta-critical as credit spreads. (The other reality is that the corporate bond market is not nearly as large or liquid as the stock market, making it much easier for the Fed to bring about its desired outcome; again, it’s too bad they didn’t realize this in 2008.)

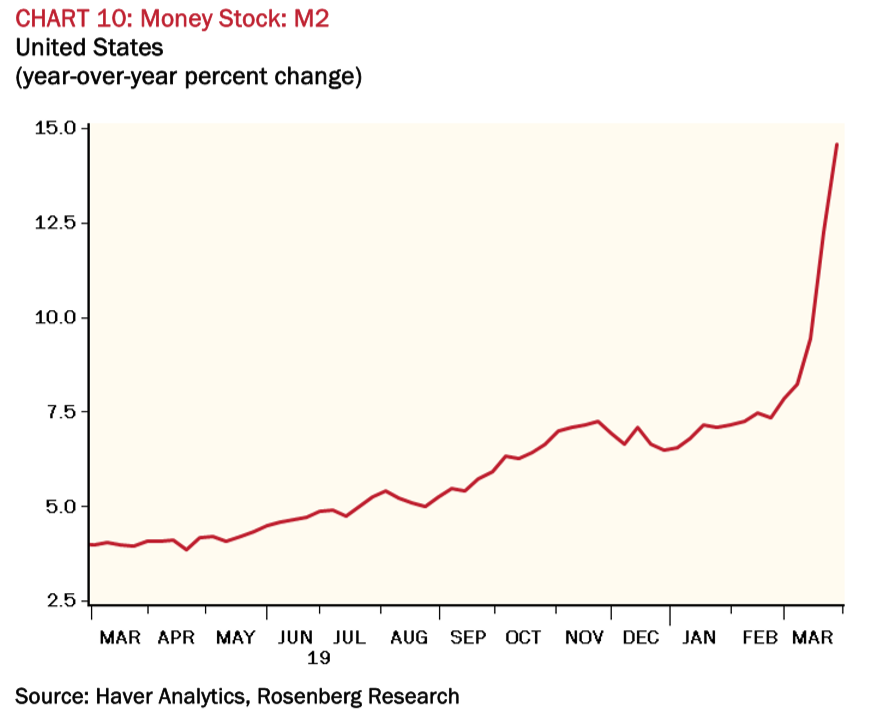

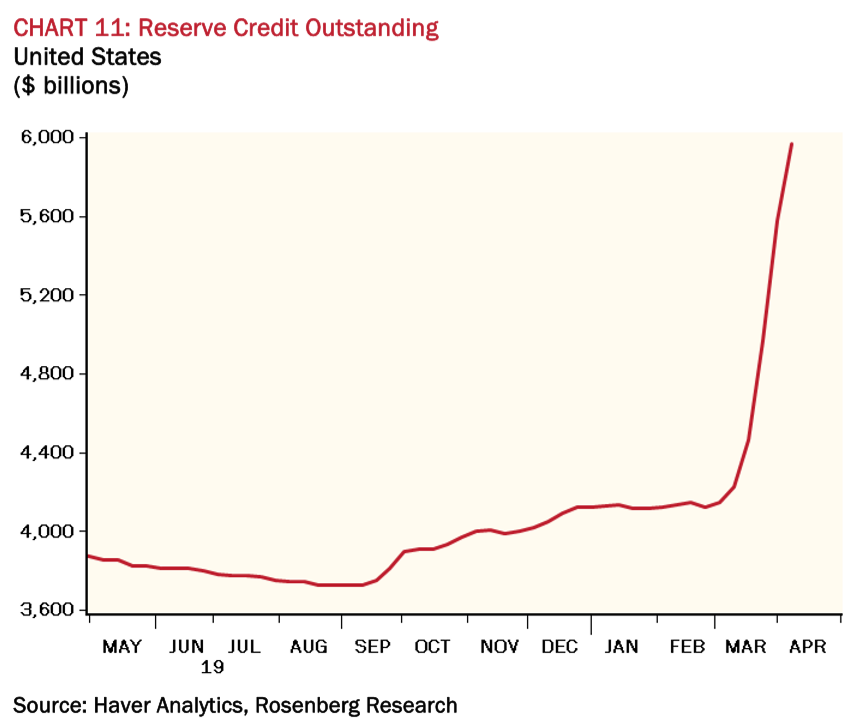

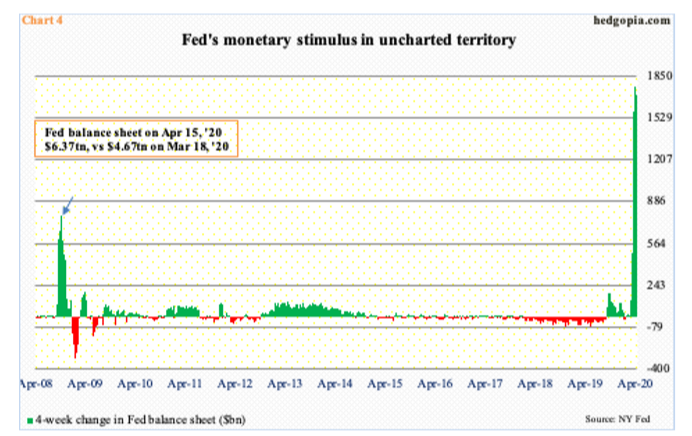

So, how extreme is the Fed’s reaction to the pandemic panic? In this regard, a few images are worth a barrage of verbiage.

Since mid-March, the Fed has increased its balance sheet (all with fake money) by $2.1 trillion. Over the prior 7 months, its holdings of government bonds and mortgages has surged by 100%, while the money supply (M2) has exploded by 90% in just a month. The Fed has said it will do all it can to prevent a liquidity crisis and it definitely is walking its talking (or printing its hinting).

This hyper-inflation of the Fed’s balance sheet has caused some independently minded types, such as billionaire hedge fund manager Ray Dalio, to remark: “I think a lot about what money is worth and believe that is has no intrinsic value…I believe that increasingly there will be questions by bondholders who are receiving negative and nominal rates while there is a lot of printing of money about whether the debt assets they are holding are good stores of value.”

What he’s effectively saying is that currencies like the US dollar are only backed by the taxing power of the US government. Further, based on the present unprecedented peacetime debt issuance and related money printing by the Fed to ensure that is done at very low interest rates, government bondholders are likely to wake up some day to the Ponzi scheme in which they are involved. In my view, and I think it’s just stating the obvious, there is no way the US can service its current debt load plus the much, much greater level of unfunded entitlements (more to follow on this subject).

Now, this is where we get into highly controversial terrain. Most pundits today think that the trillions and trillions the US government is spending, and the Fed is hoovering up via QE5, is not a problem and is certainly not inflationary. They often cite Japan’s experience of much greater deficit spending and central bank debt monetization, where, in that case, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) printed vast sums to buy up a far greater percentage of Japanese government debt than the Fed has…thus far. Remarkably, the BOJ was able to achieve this without triggering even mild inflation, much less of the hyper-variety.

It’s a valid point well-summarized by Ned Davis Research’s Joe Kalish in an email he sent me last week in response to a question I posed him about the unsustainability of the US debt situation: “There are options other than inflation, depreciation, or default. Default is not an option, since we do not owe federal debt in other currencies, like Argentina. Inflation will not be an issue since there has been a huge demand (and supply) shock. Dollar depreciation will be slow, since currencies are relative value and every country is facing the same issue, so nobody has a real advantage. Post WWII we essentially grew our way to a lower debt/GDP.

But why do we need to pay it down? Japan has carried a large amount of debt with the BOJ owning much of it with no inflation, so what’s the problem? The problem comes if and when the private sector fully recovers (eliminates the output gap) and the federal government competes for resources. That’s when you get inflation and crowding out. We’re a long way from there.”

There’s much I agree with in Joe’s analysis. Certainly, he’s totally correct that the US government can’t explicitly default on its debt because it’s all in US dollars and, as we’ve seen, the Fed has its magical digital printing press. He’s also on solid ground when he points out that nearly all competing countries, and their currencies, have sovereign debt-servicing problems similar to the US, or even worse. But where things get shakier is with inflation.

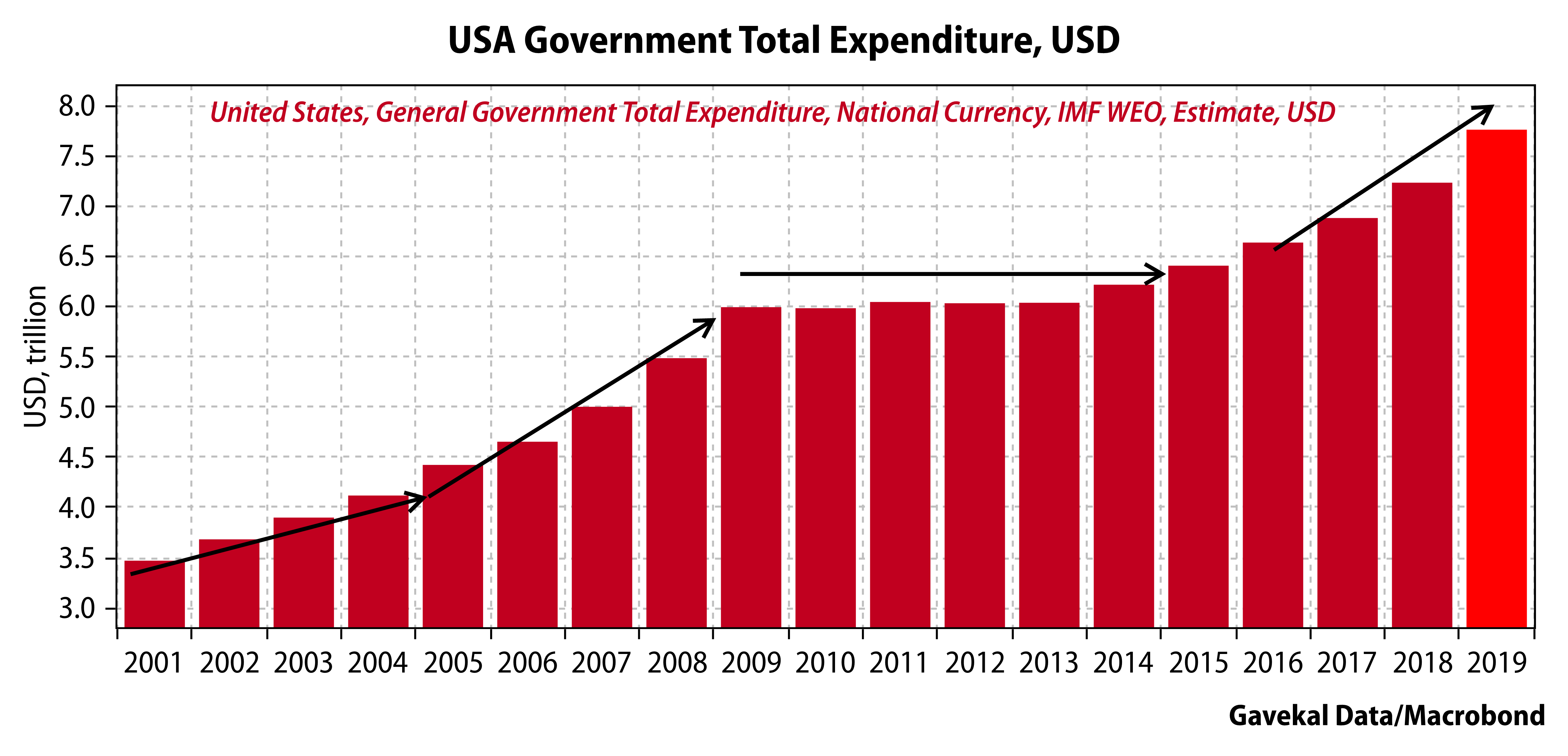

For sure, the dominant view right now is that since QEs 1 through 4 didn’t create inflation, why should QE 5? As long-time EVA readers may remember, I was in the minority back in 2009 who felt that first shocking act of money fabrication would not create an inflation problem. My argument at the time was that the velocity of money was crumbling, and this would make it extremely hard for inflation to rear its coyote-ugly head. The private sector was so shell-shocked by the financial crisis that it wasn’t in a spending mood. In addition, the Federal government enacted a series of spending restraints so that total expenditures flat-lined at around $6 trillion per year—until Donald Trump was elected.

Consequently, what we had was an easy Fed but a somewhat “austere” (at least as far as fiscal austerity goes these days) federal spending environment. But that second part is not at all what we are seeing these days. Per the above chart, the US was already experiencing a worrisome rise in Federal outlays even before COVID19. Now, we may see expenditures nearly double in a year’s time, perhaps two.

My dear friend and partner Louis-Vincent Gave summed this up very well a couple of weeks ago:

“I start off with the reality that what really matters is the interaction of fiscal policy and monetary policy. Specifically, we can have:

And same on the fiscal front

Then, you can have any combination of the above, leaving you with 16 possible outcomes… I think if you look at the US, from 2011 to 2016, you had either “very loose money” or “loose money” and tight fiscal. Then (in) 2017, you had tight money and tight fiscal. Then, in 2018 you had tight money and loose fiscal. You then had the sell-off (the late 2018 near-bear market) which led to 2019 having loose fiscal and loose money. And now in 2020 you have crisis money and crisis fiscal.” (Emphasis added)

That last point by Louis is precisely why conditions are radically different today than they were when the Fed’s QEs 1 through 3 only produced asset price inflation (as its monetary torrents flooded into financial markets vs the real economy). Today, we’ve got the “progressive” economists’ dream of US government money being directly deposited to consumers and businesses, the once only hypothetical “helicopter” money.

However, Joe Kalish is also correct in noting that inflation is MIA for now; rather, we’ve got deflation due to mass unemployment and enormous amounts of unused capacity in the system (empty factories, airplanes sitting on the ground, only 20% of hotel rooms occupied, etc). But fast-forward into next year and conditions could be dramatically different.

Millions of households will have accumulated cash both thanks to limited ways to spend it for now and the historic amounts of Federal support payments. Once the lock-downs ease, the pent-up demand will likely collide with a much slower supply response. One of the first areas this should show up is in food prices where farmers are destroying unsold crops and ranchers are euthanizing their herds. This is due to logistical challenges in getting their products to market and also that grocery store requirements are very different than restaurant needs (packaging, etc). But shortages are probable in a wide range of products and, especially, services (there may be a lot fewer hair salons around when people can finally get out to use them).

Another big difference is deglobalization. The trade wars were already causing manufacturers to want to “re-shore” closer to end markets. Now, with the pandemic, the desire to produce nearer to home for US companies is elevated even further. This is nearly certain to put upward pressure on the CPI (good-bye China price!).

Similarly, the era of “just-in-time” inventories is likely mostly in the rear-view mirror. Instead of businesses running with very lean stockpiles, there will be a much greater tendency to have more inventory on hand to cope with future supply shocks. This, too, adds inflationary upside over time.

The good news, as pointed out by regular EVA contributor Gerard Minack, is that you don’t go directly, without passing “GO”, from a deflationary bust, such as we have now, to an inflationary boom, much less bust. There almost has to be a sweet-spot interlude where deflation turns to mild inflation and growth accelerates without creating capacity constraints. This is the “Goldilocks” scenario so beloved by the stock market. We could be in that dream state—temporarily—in the second half of this year and/or, perhaps, the first six months of 2021.

The reason for the “temporarily” is that I don’t see how we avoid a faster-than-expected inflation burst over time—and I haven’t been worried about inflation since 1981! One of JP Morgan Asset Management’s senior strategists, Karen Ward, summed this up concisely in a recent Financial Times article. To wit: “…there is also a risk that policymakers leave the stimulus in place too long. They have demonstrated in recent years a clear tendency to err on the side of delivering too much, rather than too little. Populations will not tolerate talk of a new wave of austerity so soon after the last. It is possible that the monetary and fiscal taps remain turned on for longer than necessary, allowing medium-term inflationary pressures to build.”

Think of it this way: the US government is vectoring to spend an additional $5 to $7 trillion, the equivalent of 5 to 7 Amazons, in order to merely get GDP back to where it was in February. And what will we have to show for it? Will we have trillions of dollars in new bridges and highways? No. Will we have defeated Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, putting America in a position to re-build Europe and Japan? Nope. Our best hope is to just get back to some semblance of normal economic activity.

What we will have gotten in return is a Himalaya mountain range of debt. Previously, we had K2 and now we will get Mount Everest, as well. This multi-mile-high mass of debt will prove to be the gift that keeps on taking. We are now circling the runway of the Ultimate End Game. At this point, it’s time to do a brief flashback to what was, in hindsight, one of the most important chapters of Bubble 3.0.

In my April 2019 chapter, “Can an Acronym Save the World?”, I focused on the arresting new concept (at the time) of Modern Monetary Theory, popularly abbreviated as MMT. Way back when, ohhhh about 13 months ago, this concept was primarily embraced by Bernie Sanders and, to a somewhat lesser extent, by Elizabeth Warren, as well as an eclectic collection of economists and financial pundits. Shortly thereafter, however, it dawned on some, including this author, that Donald Trump and his reluctant Fed ally, Jay Powell, were already practicing a form of MMT-lite (the aforementioned $60 billion per month of fake money due to problems in the repo market starting last September).

The MMT theory holds that the US government can spend without restraint—save one, discussed below—because, as previously observed, it borrows in dollars and the Fed can create as many of those as are necessary to pay the government’s bills, including interest.

The main proponent of MMT is a telegenic and persuasive economist by the name of Stephanie Kelton. Considering what’s happening today, Ms. Kelton should feel validated in the extreme and, based on a recent interview in The Financial Times, she does. In a stunningly short timeframe, what was considered to be a wild and fringe theory is now the economic law of the land…for better or for worse. And that last phrase is the real kicker.

In the aforementioned interview, Ms. Kelton was quoted as saying: “I think the speed with which Congress has acted, not once, not twice, but three times, without a moment’s pause about the pay-for, the deficit…they’re not even trying to pay rhetorical tribute to the future…I keep saying we don’t have a debt problem, we don’t have a deficit problem. We have a language problem.”

Besides quoting the profound thinkers from Fleetwood Mac: “Don’t stop thinking about tomorrow. It will soon be here,” I’d also like to say: First, I have no illusions Congress is going to stop at three jaw-dropping stimulus programs and, second, I don’t have a language problem with unbridled deficit spending, financed by a print-happy central bank; I have a history problem.

History is unmistakably clear that MMT doesn’t work, even for countries that can issue debt in their own currency (though this ability does allow them to perpetuate the prosperity illusion for a much longer time). The main reason it doesn’t work is that, at some point, bond investors and/or the general populace wakes up to the con game underway. This is when the one restraint mentioned above that MMTers allow—namely, inflation—comes into play. Ms. Kelton and the others, like Greg Ip, assume that should consumer prices begin to rise at a destabilizing rate, the Fed will step in and tighten to bring it under control. To which I say—really??!!

The Fed will actually have the fortitude to raise interest rates when the total Federal debt erupts to around $30 trillion? Each 1% rise in rates will cost the government an extra $300 billion. Not only that, higher rates will also hurt the private sector which has—and will continue to have—far too much debt.

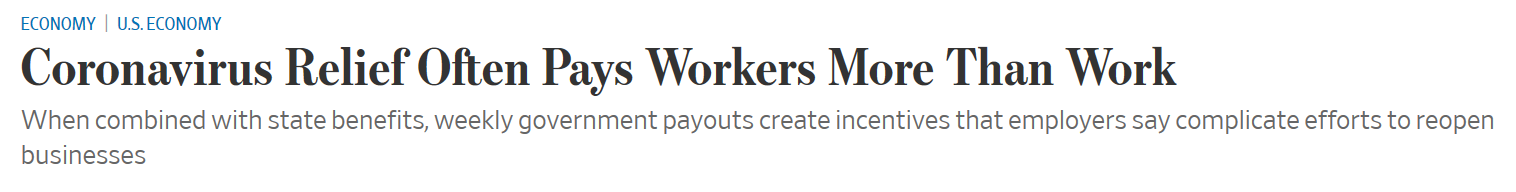

Beyond the Fed, the government is sending out hundreds of billions of income support payments (additional spending will be in the trillions). Millions of workers are actually getting a pay increase not to work due to receiving both state unemployment benefits and federal assistance. Per the Wall Street Journal article below, there are increasing reports of employees telling business owners they won’t return to work when asked. Just as it will be difficult for the Fed to aggressively raise rates to fight any inflation spike, it may be hard for the government to exit income support programs even when conditions improve.

Source: Wall Street Journal

As Louis-Vincent Gave has written on this issue: “Is there any doubt the end result of all this will be: (1) The start of some kind of Universal Basic Income in most Western countries and (2) Financed by MMT (the Magic Money Tree)…For today, the only promise we have from governments is that currencies will be debased and sacrificed.”

Now we’re really zeroing in on the target. The US will survive and eventually thrive but the US dollar, as we know it, may be the sacrificial lamb to avoid class- and intergenerational-warfare. It is likely to be sacrificed on the altar of something I think you’re going to hear much more about in upcoming years: a debt jubilee.

Because total US govt liabilities, including estimates of $50 to $100 trillion in entitlements like Medicare and Medicaid, are simply unaffordable, some kind of debt “reset” is nearly inevitable. (There are those who might challenge that figure, but I’d further add that the government is now assuming countless trillions in additional liabilities from corporations and I have a hard time believing the same won’t happen with municipal debt. Much of it is almost certain to be forgiven.)

It would be political suicide to attempt to drastically reduce the benefits Americans have been promised and have come to expect. Let’s face it – we feel very entitled to our entitlements! Thus, what we’re looking at is an endgame plan along the lines of the Fed canceling half of the Treasury debt it holds (which might soon exceed $10 trillion) in return for a non-interest bearing—i.e., zero-coupon—100-year maturity bond. Presto, chango, debt crisis solved! Was that easy, or what?

Logic would indicate that there will, of course, be a price to pay. One of the most important thought exercises of the next few years is likely to be what form that will take. Will it be like Japan where all the money its central bank has manufactured and used to buy government and corporate bonds, as well as stocks, just sits idle in its financial system? Or will it behave in a much more volatile way? As the venerable Ned Davis recently wrote, the key tell may well be money velocity*—the rate at which money turns over in the economy. For now, that is once again falling and will likely continue to do so for the next few months. After that, it’s a much tougher call.

If the Fed ends up injecting around $10 trillion into the system AND the federal government deficit spends most of that, including in direct payments to consumers and businesses, it’s hard to believe a debt forgiveness in the trillions won’t be highly inflationary at some point. This is NOT the old QEs that printed but didn’t spend. If the Fed magically cancels the treasury debt it has bought, those trillions will still be in the system and if they start circulating, then things, such as inflation, will heat up very rapidly. A far smarter man than I, Bill White, quoted at the top of this letter and one of the few to see the last financial crisis coming, has observed that countries can move from deflation to hyper-inflation quite quickly once they resort to the type of actions being taken today. (He further believes some type of debt moratorium will be needed.)

Yet, putting aside the inflation argument, the fact of the matter is there is simply way, way too much debt in the world these days and governments are frantically piling on more by the nanosecond. We all know it will never be paid back but the bigger question is can it be serviced? In other words, can the interest on it be covered? With interest rates around zero or below on most government debt, that seems like a non-issue but think about what this means long-term: interest rates gone missing forever. It’s terrible news for the enormous global Baby Boomer investor cohort which is now also seeing dividends cut in growing numbers on their equity portfolio. Talk about a double-whammy!

The story of countries that have resorted to ever-increasing government debt levels combined with non-existent interest rates is one of very low economic growth and depressed stock prices. Both Japan and Europe have stagnated economically for years while the Japanese stock market has gone nowhere since 1990 (except down) and the European stock index has flat-lined since 2000. That’s why I don’t find the “sunny” view of Japan’s experience with these policies to be comforting.

It’s also clear our economy and financial system have become increasingly fragile. The fact that the kind of sheer collapse we’ve seen since February can happen almost overnight, speaks volumes about that fragility. But as the S&P fights its way closer to even for the year, the attitude is taking hold that the pandemic won’t be a big deal in the long-run. Obviously, I don’t buy that logic. In my view, the repercussions of this disaster will be with us for a great many years, including an increasing loss of faith in policymakers and international organizations (such as the now disgraced World Health Organization).

Many, including Pres. Trump, have likened the battle against Covid-19 to a war. If they’re right, it’s important to remember that wars almost always lead to shortages. We’ve seen a wide range of those with medical supplies and household products. But now we’re also seeing supply deficiencies in items as disparate as wind-turbine blades, gold bullion, uranium, and, as mentioned, certain food categories. Overall, there is still a glut of most commodities, products and services. But 2021 might just be the year of shortages as demand recovers and supply struggles to keep up. Oil might even shock the world by moving from massive excess inventories into a shortfall condition over the next 18 months or so.

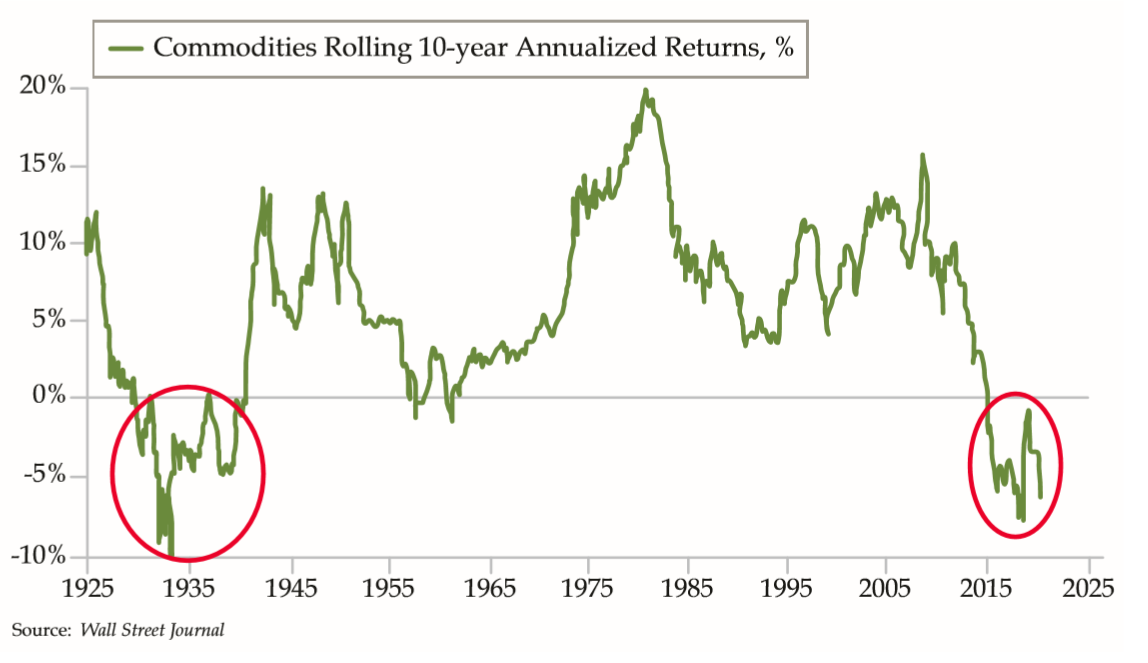

This newsletter has repeatedly urged readers to accumulate gold and gold-related securities over the last year. These have now entered a low-profile bull market as the oldest known money has been making new highs against most major currencies, ex-the US dollar. Even against the greenback, gold has experienced a multi-year upside breakout and is not far from an all-time high. Near-zero government bond yields and de facto MMT create a dream scenario for gold, a reality to which the market seems to be gradually awakening. But there are many other so-called hard assets, besides gold, that may be poised for a surprising surge, with most investors woefully underweight commodities, in general, and precious metals, in particular.

Inflation arises when there is too much money, chasing too few goods and that could be the story of next year. There’s no doubt about the “too much money” part and if shortages do become far more commonplace, the following chart might look very different in a few years time. In other words, we could be on the verge of one of those seismic shifts in the financial markets that seem to happen roughly every decade. Are you ready for that? If not, the good news is there’s still time…for now.

![]()

*For monetary purists/geeks, money velocity is a dependent variable, i.e., it doesn’t drive inflation it merely indicates when the economy is growing faster than the money supply, indicating rising money velocity.

Corrections, clarifications and amplifications from last week’s issue:

In the Likes/Neutrals/Dislikes section, the commentary on pipelines/MLPs should have read:

In the section referring to how the Fed plays both arsonist and fire brigade, the line that read:

Under the amplification heading, the most remarkable statistic I’ve now seen on the coronavirus is that in Taiwan, with a population of 23 million people, there have been just six COVID-related deaths.!

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.