"The problem is a moral hazard. If the Fed responds when markets turn down but doesn’t suppress exuberance when market are up, private actors will have an incentive to take on more risk than they otherwise would."

-DANIELLE DIMARTINO BOOTH, regular guest on CNBC, former senior advisor to ex-Dallas Fed president Dick Fisher, and author of Fed Up

The ongoing EVA series with excerpts from my upcoming book (tentatively titled “Bubble 3.0, How Central Banks Created the Next Financial Crisis”) is getting a lot of attention from clients and readers. Depending on which camp people sit in – see-no-trouble bull or too-lightly-invested bear – the responses either strike a dispiriting or encouraging tone.

However, regardless of pro or con feedback, I feel compelled to continue to write on with conviction that we are currently in the midst of the Biggest Bubble Ever (BBE). And, as I’ll cover in a future chapter, I believe the evidence is persuasive that it’s also the LBE—Longest Bubble Ever.

If you are just joining us in the middle of this ongoing series – which will culminate in a full-length publication – please take a few moments to review the prior installments in the series:

For those continuing on with us in our journey to inspect and dissect the BBE, we will be moving on with Part II of last week’s chapter by completing our examination of the two most recent bubbles and busts. This is much more than an academic exercise. The crucial point is how the reaction to those disasters has now pushed the major asset classes—stocks, bonds, and real estate—to their highest collective valuation in history, leaving us exposed to yet another painful return to reality.

BUBBLE 3.0: HOW DID WE GET HERE? (PART II)

As the “Roaring ‘90s” came to a close, and the calendar (and computers) flipped over into a new century and millennium, tech stocks displayed no evidence of suffering an early-year hangover. Y2K turned out to be a non-event and the Nasdaq kept rocketing. By early March of 2000, the “NAZ” was up another 24% (or at about a 208% annualized rate), bringing its surge from the lows of the 1998 Asian crisis trough to a mind-blowing 257%. Incredibly, this monster move occurred in less than a year-and-a-half. Then, virtually overnight, the tech world shifted on its axis.

There are typically multiple pin thrusts that puncture a bubble as immense as the one created by the tech/internet mania and this explosive deflation was no exception. The first prick was, in hindsight, the failure of several new issues by dot.com entities. Even as early as April, 2000, the 149 initial public offerings (IPOs) that had already occurred so far that year were down an average of 45% from their first-day close (though this was typically up, sometimes considerably, from the IPO price). Suddenly, the initial public offering (IPO) market was no longer a gullible supplier of limitless funding—not to mention a fabulously lucrative exit strategy for the original investors.

The shockwaves reverberated quickly through the start-up ecosystem. With the IPO market on its heels, venture capital-types became increasingly choosy about which business plans they would finance. The torrent of money that had been sloshing through Silicon Valley and Seattle stopped almost as if someone had closed the gates of a giant sluice. As always occurs when a boom goes bust, the losses came fast and furiously. By the summer of 2000, the Nasdaq was down an ulcer-producing 35%.

Another factor behind the plunge, ironically, was good news about Y2K. The uneventful transition removed the Fed’s rationale for not hiking rates further to cool off the ripping economy and equity markets, at least when it came to tech and certain blue-chip growth stocks. (As an interesting side note, most stocks peaked in early 1998 and value issues in particular entered into a stealth bear market that lasted for roughly two years.) In January of 2000, the Fed hiked its overnight rate to 5.75% (yes, those were the days when holding cash wasn’t penalized; in fact, it was earning a net-of-inflation yield of 2%).

This would prove to be the first of seven tightening moves the Fed initiated from mid-1999 through mid-2000. Despite the accelerating tech meltdown, the Fed hiked again in June, 2000, pushing the fed funds rate up to nearly 6 1/2%. With inflation running at 3 ½% that year, the real return on money market-type accounts rose to roughly 3%. In those days, cash was definitely not trash and this obviously posed a competitive threat to the stock market—especially once the thrilling gains had turned into chilling losses.

As 2000 came to a close – and what would turn out to be the world-shaking year of 2001 began – hopes were high that the worst was over in tech land. This seemed a reasonable conclusion given that the Nasdaq finished 2000 down a stunning 61.2%! Yet, unfortunately, for all those true believers in the glorious future for the internet and high-technology (of which there were legions), the carnage in tech intensified.

Even prior to the horrific events on September 11th, 2001, the Nasdaq fell another 31.2%, leaving it down 66% from its March 2000, apex, before a feeble rally occurred that summer. The utter nightmare of the 9/11 terrorist attacks—which would reverberate around the planet for years to come (and still does)—only intensified the tech devastation. From the peak of the summer bounce to the post-9/11 low, the Nasdaq melted by another 35%, before a vigorous year-end recovery erased most of the losses caused by the 9/11 panic. Regardless, for all of 2001 the Nasdaq had swooned an additional 20.8%, on top of the 61.2% shellacking in 2000. Once again, many assumed the worst was over. They were once again wrong.

Notwithstanding some rousing rallies during the two and a half year bear market in almost all things tech, once the “NAZ” finally hit bottom in the fourth quarter of 2002, it had fallen from 5000 to 1100, a monstrous contraction of 78%. Not since the Great Depression, when thousands of banks failed and America looked to be on the brink of sheer collapse and/or a social revolution, had a major index declined by this magnitude.

The Fed’s earlier unwillingness to put out the raging speculative fire by raising margin requirements had come back to haunt it—and the world—as nearly all stocks markets were ferociously mauled. Alan Greenspan’s “Maestro” reputation was in serious jeopardy and his failure to follow-through on his 1996 “irrational exuberance” message was widely criticized. The Greenspan-led Fed then proceeded to make a difficult situation much, much worse.

With hysterical pressure from high-profile sources, especially the New York Times’ Paul Krugman (who, in 2008, ironically, would win a Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions to New Trade Theory and New Economic Geography), the Fed kept cutting its overnight rate until it got down to the unheard of level of 1% by June, 2003. Despite the fact that the US economy only endured a mild recession in 2001—most remarkable given the twin shocks of the tech bust and September 11th—Mr. Krugman literally begged for the Fed to create another bubble. Intentionally or not, Mr. Greenspan and his esteemed colleagues at the Federal Reserve Board—which included future Fed chairman Ben Bernanke—did exactly that.

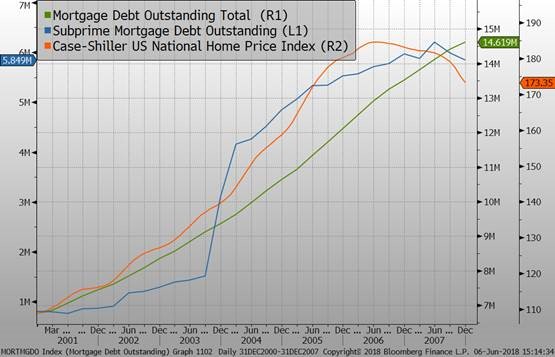

Even as the US bounced back from its technical recession (GDP actually rose 1% in 2001 and 1.8% in 2002, despite the tech crash and the terrorist attacks), the Fed left its overnight rate at 1% through May of 2004. This negligible cost of short-term money further inflamed an already red-hot housing market. With adjustable rate loans (ARMs) becoming all the rage, in order to fully exploit the collapse in short-term interest rates, the stage was set for lift-off into the bubblesphere.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal (as of June 7, 2018)

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal (as of June 7, 2018)

It was at this point that both the mortgage industry and Wall Street formed the unholy alliance that would become immortalized in Michael Lewis’ blockbuster chronicle of this era, “The Big Short”. Mortgage originators were lavishly incentivized through their cornucopia of fees to extend credit to nearly anyone who could fog a mirror. Unlike in by-gone days when traditional banks and S&Ls would create loans and often hold them on their balance sheet (thereby, ensuring a fair degree of prudence), the new breed of “originate and securitize” mortgage players had no residual skin in the game. By securitizing (i.e., bundling a large number of mortgage into a package and selling them to Wall Street), the originator off-loaded the credit risk. Ergo, a tremendous moral hazard was created at the initial level where the loan was created.

The next moral hazard was Wall Street (I know, what a shock!). Its clients, both institutional and retail, were clamoring for yield. As usual, The Street was thrilled to comply—and supply. After all, it had only been a couple of years earlier when savers and investors were earning 6 ½% on cash (and longer-term investment grade corporate bonds and preferred stocks were yielding 8% to 9%). In what was to be a sneak preview of the conditions that would last for so many years in the following decade (what this book refers to as Bubble 3.0), Wall Street showed extraordinary ingenuity in creating vehicles to satisfy the ferocious appetite for yield. It began to create CDOs by the droves, those securities more formally known as Collateralized Debt Obligations that would be at the epicenter of the coming 9.0 planetary financial earthquake. Increasingly, these CDOs were populated by the subsequently notorious sub-prime mortgages. Why? Because of their lofty yields and, incredibly, as we will see in a moment, their perceived low-risk.

To that point, and next up on the moral hazard list, were the rating agencies. Entities such as Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s (the Big Two, with Fitch’s a distant third), were compensated not by the buyers of the securities they rated but by the issuers—meaning the Wall Street underwriting machine. To reprise a quote from the start of this book by Warren Buffett’s long-time partner, Charlie Munger, “show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.” In this case, the outcome was a steady stream of AAA-ratings on mortgage securitizations comprised totally of sub-prime loans. The logic, such as it was, for this seemingly absurd alchemy of turning junk into gilt-edged securities had to do with the supposed magic of “tranching”.

In plain language, this meant that a given pool of dodgy mortgages was sliced into pieces from the most- to the least-protected. It also meant that once the inevitable defaults began to roll in during the next recession, the lowest-rated tranches would take the first hits. Considering the increasingly toxic credit characteristics of mortgage lending during that era--“Liar’s” and “Ninja” (No Income, no job…no problem) loans, and negative amortization mortgages, plus the very widespread use of ARMs)--it didn’t take a financial wizard to realize it wouldn’t require much of an economic downturn to totally nuke the riskiest tranche. But that wasn’t to be the big surprise of this egregious example of mass greed.

One could make the argument that the rating agencies’ failure to do its job was the most indefensible. After all, the mortgage industry is in the business of making and selling as many loans as the markets and the regulators (more on them shortly) would allow. The same is true with Wall Street. But the rating agencies are supposed to be the safeguard, warning professional and amateur investors if securities are high risk—or has the potential to be under adverse conditions.

Certainly, in the past, the assumption was that if a security was rated AAA, as so many of the sub-prime CDOs were, that it could withstand even a serious recession. In fact, it was common for a very high- grade debt instrument to actually rise in value during tough times, the well-known flight-to-quality phenomenon. But, regardless, the belief was that they should at least hold their own during hard times, as they had during the 1930s. The crisis of 2008 shattered that precedent.

The operating assumption in bestowing a AAA-rating on sub-prime CDOs was that the home default experience would be similar to past down-cycles. Few, other than the cranky renegades who were to become stars of “The Big Short”, were connecting the dots between incredibly lax and reckless mortgage underwriting, home prices that were the furthest above their trend-line in history, and, as a result, affordability that was off-the-charts awful.

In his after-the-crisis apologia, Alan Greenspan would muse that it shocked him how financial institutions could have been so imprudent (despite the fact that history was loaded with recurring examples of exactly such imprudence). He had also assumed that securitization was a good thing as the leveraged banking and lending system was off-loading its credit risks to entities like mutual funds who typically were cash buyers. What he somehow missed was that the banks’ investment departments were as furiously accumulating these “securities” as their mortgage divisions were disposing of them.

Meanwhile, regulators like the SEC, the FDIC, and the Comptroller of the Currency, were in a deep-REM slumber. Nothing was done to slow down, much less stop, the craziness. It wasn’t like they couldn’t see what was happening with home values and mortgage debt. The numbers were hiding right there in plain sight.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal (as of June 7, 2018)

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal (as of June 7, 2018)

The New York Fed, given its proximity to Wall Street, should have been in its grill, pushing back vigorously on the blatant shenanigans. Instead its president (and future Treasury Secretary) Timothy Geithner gave a speech in 2006, close to the top of mania in which he said: “You are meeting at a time of significant confidence in the strength of the global economy and in the overall health of the financial system…the core of the US financial system is stronger than it has been in some time. Capital levels are higher and earnings stronger and more diversified…We have seen substantial improvements in risk management practice and in internal controls over the past decade.”

The fact that Mr. Geithner could be appointed Treasury Secretary AFTER the crisis that he had no clue was brewing, and it had morphed into the worst financial panic since the 1930s, is certainly testament to the inherent job security in working for the government. But it is stunning—and more than bit terrifying as an American–to think that just two years later, everything he had spoken turned out to be complete nonsense. (In a later chapter, we will examine similar language being used by senior Fed officials in recent years.)

Sadly, nearly all Wall Street strategists and money managers were oblivious or in total denial. (The smug portfolio manager portrayed in “The Big Short”, who completely blew-off the concerns of the housing bears, has an uncanny resemblance to Legg Mason’s former star, Bill Miller.) However, there were a few brave and insightful exceptions. My good friend Danielle DiMartino Booth, who is cheering me on as I write this book, was one of them. Danielle is the author of the critically acclaimed book “Fed Up” and was a senior advisor to the then-president of the Dallas Fed, Dick Fisher. As such, she had a courtside seat to the inner workings at our country’s central bank during the lead up to the crash.

In her words, which she emailed to me this week, “In late 2006, after having written extensively on the potential for the housing bubble to unleash systemic risk across the global financial system, I arrived at the Fed just as home prices were beginning to crack. I was blown away by the calm and the blind acceptance of Alan Greenspan’s misguided creed that the economic benefits of homeownership, regardless of buyer qualification, outweighed the financial stability consequences precious few within the Fed saw coming.”

(Author’s Note: Danielle just launched her new service, The Daily Feather, at only $25 per month, written by her team of insiders, analysts and thought leaders. These brief “dailies” are rich with deep understanding of how the Federal Reserve and worldwide central banks think and operate. Danielle and her associates have an extensive network of Wall Street heavy-weights feeding their team with unique insights. Please check out an example of the Daily Feather here.)

David Rosenberg, then chief North American economist at Merrill Lynch, and Pimco’s Paul McCulley were other lonely voices of caution. This author had the privilege of hearing both of them speak at John Mauldin’s Strategic Investment conference in the years leading up to the housing crash. It was a key reason why I began to repeatedly warn readers of this newsletter in 2006 and 2007 that housing posed a grave threat to markets and the economy.

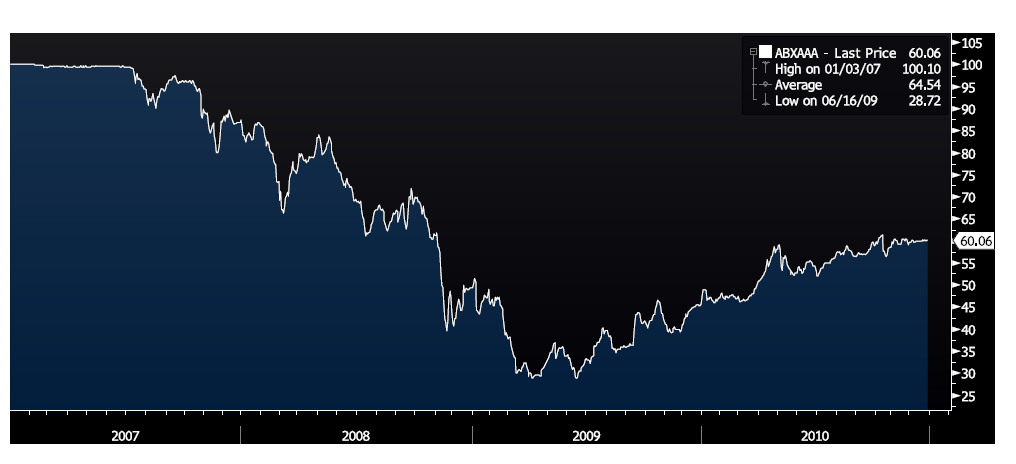

The aforementioned lowest-rated slices (tranches) of sub-prime CDOs became the first—and worst—casualties of the housing bust. Most were wiped out during the first phase of the housing melt-down. But what was really shocking—and began to threaten the global banking system—was the utter collapse of the AAA-rated tranches.

By late 2008, many of these were trading at around 30 cents on the dollar, meaning holders who typically had purchased them at or around par were sitting on losses of 70%. Since many of the owners of these instruments were banks with thin amounts of equity capital (especially in the pre-crisis days), losses like this were life-threatening. Moreover, because these were AAA-rated mortgage-backed securities (MBS) vs traditional home loans, banks were only required to have 1.6% in reserves set aside vs. 4% for traditional “whole” mortgage loans. Obviously, the 1.6% reserve was just a tad on the light side.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal (as of June 7, 2018)

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal (as of June 7, 2018)

Greatly compounding this debacle was a formerly obscure accounting rule that had been enacted in 1993, Financial Accounting Standard 115. It required financial institutions to use “fair value accounting”, more popularly (or, by 2008, very unpopularly) known as “mark-to-market” accounting. In other words, banks and insurance companies were required to value their held assets at fair market value. From 1993 through 2007, this new rule didn’t pose any serious problems (the banking industry was not a significant holder of tech stocks). But once the bottom fell out of the housing market in 2008, it quickly became catastrophic.

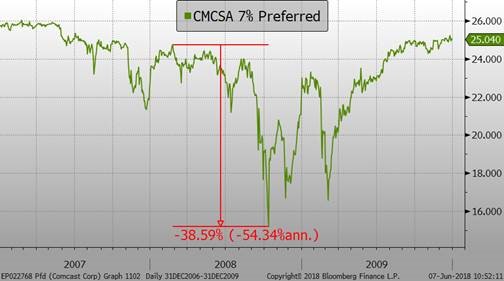

It soon became clear that the financial system was loaded with sub-prime CDOs and other derivative securities whose values had collapsed. Even traditional investment-grade bonds and preferred stocks, from companies such as Nordstrom and Comcast, plunged 20% to 40% as the planet was essentially engulfed in a global margin call.

NORDSTROM BONDS

COMCAST PREFERRED

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal (as of June 7, 2018)

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal (as of June 7, 2018)

With the new mark-to-mark rule requiring financial institutions to value these formerly low-risk assets at fire-sales prices, it became apparent than nearly all US banks and insurance companies were imperiled. Short sellers were circling even America’s strongest financial entities. The more the panic intensified, the lower stocks and bonds went. It was a classic doom loop.

Lehman failed, as did Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, along with Washington Mutual. Massive insurer AIG was saved only due to a government rescue that effectively wiped out shareholders. It truly looked like no big bank or insurance company was safe.

During this terrifying time, in the fall of 2008, this newsletter repeatedly urged the Fed and/or the US treasury to borrow (note: not print) a huge sum—like $1 trillion--and then invest the proceeds in the open market in highly-rated corporate bonds and mortgages. Because T-bill rates had crashed to almost nothing, this was virtually free money and the yields the government would be securing were in the high single digits and often above 10%. As I argued at the time, the Fed would have made a killing, an opinion which future events proved out. It also would have almost certainly arrested the panic virtually overnight.

Instead, crucial terror-gripped months went by as the government clumsily rolled out TARP which initially did very little to restore confidence. The Fed, for sure, did some wise things like guaranteeing money market funds and that did lower the panic level. And it executed the trillion dollar intervention I had pleaded for, but it resorted to the aforementioned QE (creating the funds from its computers, initiating a series of these digital money fabrications that continues to this day in many countries). Further, instead of investing the trillion where it was needed most—and where yields were astounding and prices were crushed—it invested that immense sum in the most overpriced debt securities on the planet—US treasuries and government-guaranteed mortgages.

In spite of these splashy but clumsy efforts, it wasn’t until the mark-to-market provision was defanged in mid-March of 2009 that markets began their spectacular rise from the ashes. This included bonds such as the Nordstrom’s issue shown above which, by July 2009, was back at face value, providing a 58.6% return to those brave enough to buy into the teeth of the panic. In fact, for several years after the turn, securities such as those matched or even exceeded the returns from stocks. For investors intrepid enough to buy the debt securities from AIG at 10 cents on the dollar, the return over the next four years was 754%. (By the way, Evergreen was vehemently urging readers at the time to buy these types of corporate income securities.)

Even today, there are highly intelligent investment professionals who believe the government made a monstrous error by intervening. I do not count myself among them. Despite the ham-fisted way it was done, it worked and I shudder to think what would have happened had they not resorted to measures that no one would have dreamed of mere months earlier. It was truly a near-death experience for the world’s financial system.

However, that does not exempt the Fed nor the government’s regulatory bodies from the primary responsibility for the disaster that still haunts us today. By allowing bubbles to rise to astronomical heights without trying to cool down markets (raising margin requirements, tightening lending standards, requiring more capital to be held by banks, preserving the separation of underwriting and banking, to name a few), American policymakers blew it big time.

The multi-trillion dollar question is if they have learned from their past disastrous misjudgments and should investors trust in their assurances that the financial system is now safe and sane? We will only know for certain during the next bear market and/or panic. However, the rest of this book will attempt to provide a plausible answer—hopefully, before it’s too late – to that most pressing of all questions.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.