“Gold is forever. It is beautiful, useful, and never wears out. Small wonder that gold has been prized over all else, in all ages, as a store of value that will survive the travails of life and the ravages of time.”

– James Blakely, Eureka Mine discoverer

“Gold is a constant. It’s like the North Star.”

– Steve Forbes, Editor-in-Chief of Forbes magazine

Introduction

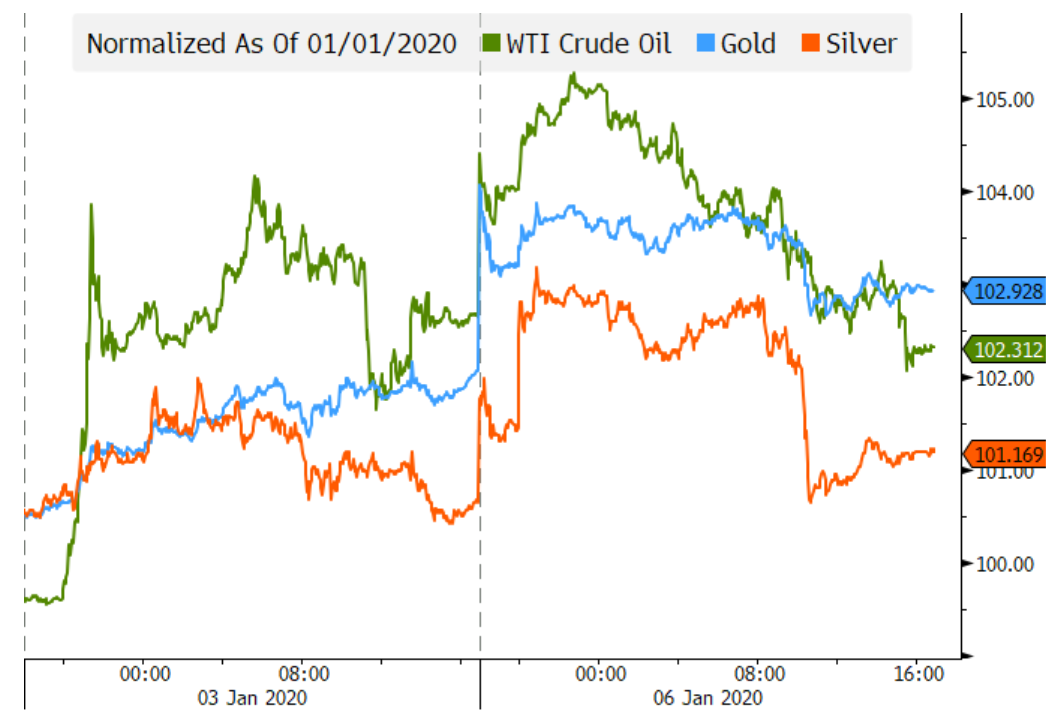

When we published our letter on hard assets in late-December, there was no way of knowing what geo-political events would unfold only a week later. But, when the US attacked one of Iran’s most beloved and decorated generals on January 3rd, shockwaves reverberated around the globe, stoking fears of further conflict in the Middle East. This fear immediately drove the price of hard assets higher, as gold, silver, and oil all spiked in the days following the death of Qassem Soleimani.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

On Tuesday, Iran retaliated to the killing of Soleimani, firing rockets at two military bases in Iraq that house thousands of American and Iraqi troops. Again, the price of gold, silver, and oil ran higher, only to reverse course the next morning as President Trump deescalated the ensuing war, signaling that the US is “ready to embrace peace”.

Despite the call to end hostilities, the question still sitting at the forefront of many minds is whether the situation in the Middle East will deteriorate further in the days, weeks and months ahead. Should the conflict intensify, there is little doubt that hard assets will be major beneficiaries. However, even when looking beyond the current crisis, there is still a strong bull case for gold, silver and oil (among other hard assets), with the caveat that they do appear over-bought on a near-term basis. (As an important side-note, the Fed continues to aggressively monetize the US treasury’s debt which means it is using money from its digital printing press to finance the government. This is another very positive factor for precious metals over time).

This week, we are presenting a bull case on gold from Evergreen’s partner, Louis-Vincent Gave. In his article, Louis reiterates and expands upon many of the points that David Hay made in his latest missive titled “Taking the Hard Way Out” on the same shimmering asset. For those growing weary of our recent fixation on gold, we ask you to bear with us for another week. The allure of the precious metal is simply too hard (pun intended) to ignore…

Gold Beyond the Iran Crisis by Louis-Vincent Gave

Gold ripped higher [between January 3rd and 6th], climbing 3% after the killing of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani [last Friday]. But that price spike cannot compensate for the undeniable fact that the last 10 years have been a tough decade for the yellow metal. After a terrific 2011, the gold price mostly range-traded in 2012, collapsed in 2013, ground lower in 2014-15, then broadly range-traded again between 2016 and 2018. In the spring and summer of 2019, gold did spring back to life, only to fade away in the fourth quarter. The latest geopolitical crisis in the Middle East has again jump-started gold’s price action, but that support may yet prove short-lived. So, what can we expect from gold going forward?

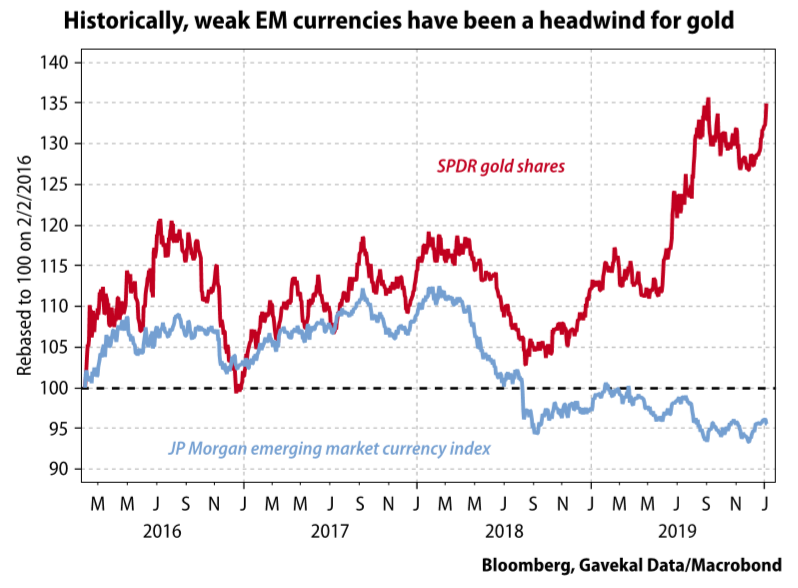

One long-held bias is that gold is just another (lower beta) way to play growth in emerging markets. After all, over recent decades most of the demand for physical gold has come from developing economies—mostly the Indian subcontinent, China, and the Middle East. So, when emerging markets boom, gold tends to do well, and vice versa. Of course, fluctuations in the US dollar reinforce this relationship; a weak US dollar tends to be good for emerging markets, and also for gold (with the opposite equally true).

This may be the first—uncomfortable—explanation for the weakness of the gold price over the closing months of 2019. Even though the US Federal Reserve launched a new round of quantitative easing, emerging market currencies continued to make new lows, reflecting the aggressive monetary and fiscal stimulus also taking place across the emerging world. And weak emerging market currencies are a genuine headwind for the gold price.

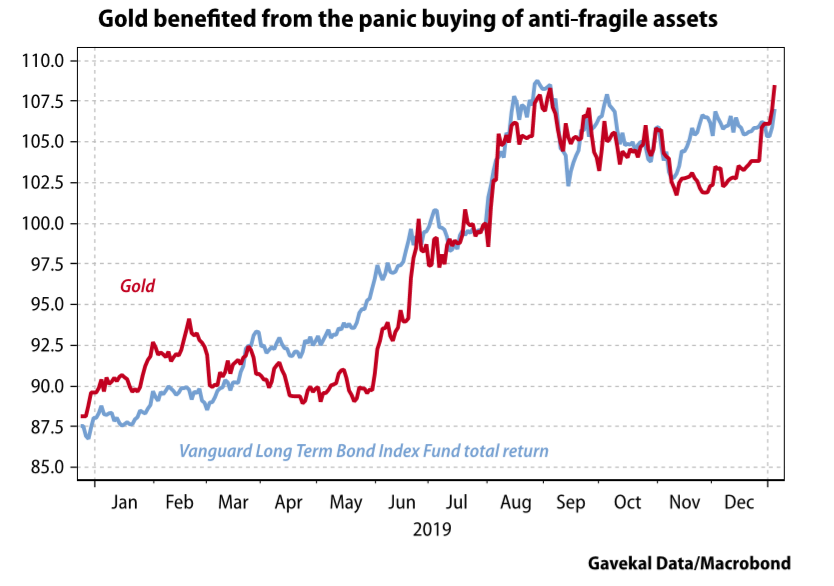

In fact, perhaps the right question shouldn’t be why was gold so weak in the fourth quarter of 2019, but why it was so strong in the spring and summer while the broad emerging markets continued to struggle? The answer is obvious enough: gold, like bonds and the Japanese yen, benefited from the panic-buying of “anti-fragile” assets. And this panic buying was driven by:

Fast forward to today and it is now fairly obvious that China has little interest in sending the People’s Liberation Army into Hong Kong. Instead, Hong Kong’s problems will continue to be handled by the city’s 31,000-strong police force. Meanwhile, the latest flare-up in US-Iran tensions notwithstanding, there is no advantage to the US administration in getting embroiled in a full-scale Middle Eastern conflagration, least of all in an election year. And while the Saudis may be willing, in the words of former US defense secretary Robert Gates, “to fight Iran to the last American,” without the US on point, Riyadh has no appetite at all for open conflict with its neighbor across the Gulf.

In addition, India’s fiscal and monetary stimulus may have encouraged Indian investors to reallocate savings away from gold and into domestic financial assets. On top of that, the Aramco shakedown likely forced some prominent Saudi families to forego gold investment in order to buy their quotas of the rather unpopular IPO. Together these factors could help to explain the lackluster trajectory of gold in the last quarter of last year.

For let’s face it, beyond weak emerging market currencies, the end of the antifragile buying panic, and the likely reallocation of emerging market savings into other assets, gold really should have done better. Consider the following:

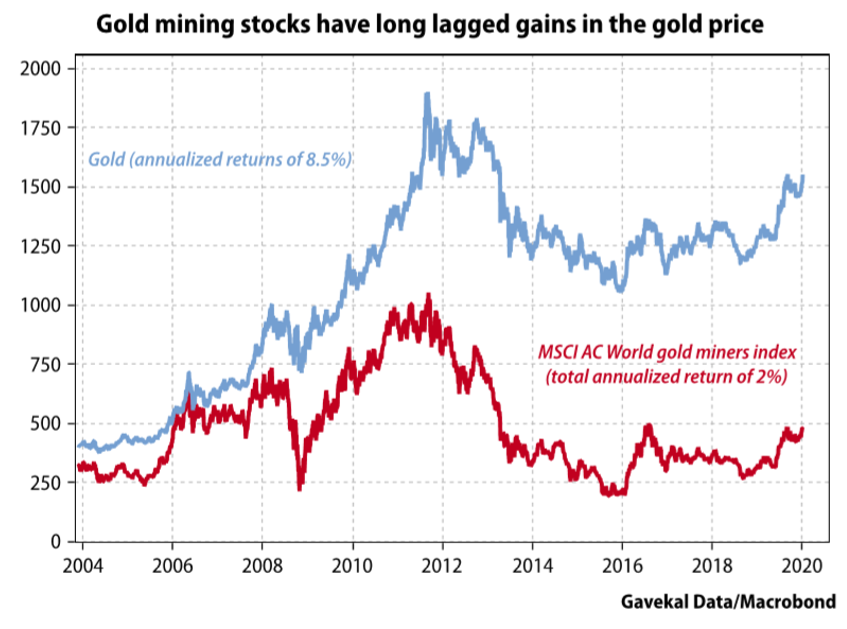

Perhaps unsurprisingly given this dismal performance, gold miners now find themselves starved of capital. This means the only path to growth left for them is industry consolidation and takeovers. Therefore, in the past few months, we have seen mergers between Newmont and Goldcorp, Barrick and Randgold, Pan American Silver and Tahoe, and Kirkland and Detour.

To some extent, this is reminiscent of the mergers that took place in the energy sector at the end of the 20th century—BP-Amoco, ExxonMobil, Conoco-Philipps, etc. It’s a textbook sign of a bottom in any given commodity’s cycle. When commodity extractors, who tend to be among the worst stewards of capital, would rather take out the competition and streamline costs than dig new holes in the ground, it tends to mean that future production is unlikely to soar. This should be supportive for gold prices.

If central banks are no longer selling gold, but are instead buying it, and if the number of gold miners continues to shrink by the week, while their inability to raise new capital suggests that new discoveries and the exploitation of large new mines are highly unlikely, then who will be the marginal seller of gold in the future? And at what price?

So, without going into the outlook for the US dollar at a time of active debt monetization by a central bank which has, for all intents and purposes, handed “the keys to the truck” to the US Treasury, and without going into the outlook for inflation at a time when the US median CPI already stands at 3%, it is possible to make a constructive argument for gold simply on future supply and demand.

As a result, it seems likely that the weakness towards the end of 2019 was nothing more than the counter-trend pullback following last summer’s panic buying of anti-fragile assets. With this in mind, even assuming the situations in Hong Kong and the Middle East deteriorate no further, it is possible to conclude that gold not only remains firmly supported—very likely at its 200-day moving average—but that it remains in a bull market.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.