“The Greek economy is not in recession. Nor is it recovering. It has collapsed.”

-Wolfgang Munchau of The Financial Times

Much to be humble about… When you write a financial newsletter, it’s easy to fall into a dangerous trap. If you’re not careful, your readers can start to accord you guru status, or, even worse, you can confer that designation on yourself. Of course, based on my stock market forecasts of the last two years, there isn’t too much risk of that happening in my case!

Yet, as I noted in our January 10th Annual Forecast EVA, where we score our forecasts from the prior year, our overall prognostication results haven’t been too shabby lately, despite greatly underestimating the final stage (in our view) of this stock market up-cycle. Regardless, the theme of this month’s “feature-length” EVA is about things I simply don’t get, which no guru, real or imagined, is inclined to admit. And, frankly, right now there are quite a few items that qualify, but let’s start with a situation that I find remarkable in the extreme.

Even if you don’t closely follow events in Europe, you are likely aware that not long ago Greece effectively defaulted on its debt. The reason I wrote “effectively” is because European authorities packaged the default in such a way as to technically avoid the dreaded “D” word. Precisely no one was fooled, however. In reality, that lovely country, with great weather and a most questionable work ethic, went bust in 2012, one year after having received a multi-hundred billion dollar bail-out, or about $20,000 for every resident, that was supposed to preclude the need for shafting its creditors.

As a result, Greece has considerately provided its creditors with a “hair-cut” (read loss) of around 50%, at least to those who are not politically connected like the various European central banks. (As an aside, despite the European Central Bank, or ECB, being the continent’s main central bank, each country continues to have its own national banking institution.) Moreover, this is not an isolated occurrence. Greece has managed to spend roughly half of the past 200 hundred years in some form of default. Clearly, the Greeks know how to make fools out of the international lending community. Perhaps these brilliant financiers need to remember the simple adage, “Beware of Greeks bearing bonds.”

It wasn’t in the distant past, but rather just a couple of years ago, when Greece’s repetitive deadbeat status caused its interest rates to vault into the 35% plus range. Given that it was unable to service its Olympus-like mountain of debt even at low rates, such yields forced the aforementioned stiffing of creditors, especially those from the private sector.

One might rationally conclude that after a costly bailout and a huge debt write-off, Greece would have its overall level of indebtedness down to a manageable amount. Similarly, if that nation was ever able to borrow at reasonable rates it would be logical to assume this would only happen as result of debt being at exceedingly modest levels, especially given its history as a serial welcher. Such reasoning would be thoroughly plausible but, alas, dramatically off the mark.

Notwithstanding stiffing its lenders, which cut its debt-to-GDP ratio by 40% and its total debt outstanding by 20%, Greece government indebtedness as a percent of GDP is back up to close to 180%. This is in contrast to the US, certainly no paragon of fiscal virtue, at roughly 100%. But, you may rush to point out, surely they must still be forced to pay exorbitant interest rates for the privilege of positioning for their next default (which I’ll go out on a limb and say is just a matter of time, and maybe not much at that).

“Surely”, at least if you consider 6% adequate compensation for holding a bond that will likely end up worth 50 cents on the dollar or less. The new math is beyond my comprehension, because that strikes me as a negative return, unless Greece can avoid default for a great many years. (If you believe that, I have some Puerto Rican bonds to sell you at par!)

Remarkably, this bizarre state of affairs goes well beyond the Greek bond market.

When PIIGS fly… In case you think that Greece is a special (though utterly inexplicable) case, I have news for you: The list of “peripheral” European countries borrowing at yields that should be reserved for dependable, if not pristine, borrowers is a lengthy one. In fact, it involves all of those nations that once were known by that affectionate acronym—the PIIGS (now admit it, you haven’t heard that in so long, you almost forgot about what it stood for).

Italy, for example, is not far behind Greece in the debt accumulation derby. It was once one of the top ten stock markets in the world, but it long ago dropped off that table into irrelevance. When it comes to bonds, though, it is a very different story. The little country (and economy) of Italy now represents the third largest bond market on the planet. While that might sound impressive, what it really speaks to is how immense its liabilities are in relation to the country’s economic wherewithal.

Debt-to-GDP is presently 130% and steadily rising. Obviously, this is better than Greece (isn’t that greatly reassuring?), but it is high enough to justifiably qualify for the lethal words “debt trap.” In other words, Italy’s chronically sluggish economy can’t grow fast enough to service the debt on that towering total. When this occurs, there are really only two options: 1. Create high inflation, thus depreciating the outstanding debt, or, 2. Do what Greece did, and stiff your creditors (which is always much more pleasurable if they are domiciled elsewhere).

The problem for Italy, as well as the other erstwhile PIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain), is that it no longer controls its money supply. That privilege and responsibility resides with the ECB. Ergo, it is unable to inflate away its obligations, leaving option 2 as the only viable choice, unless, that is, you believe Italy is suddenly going to start growing at an emerging market-type clip.

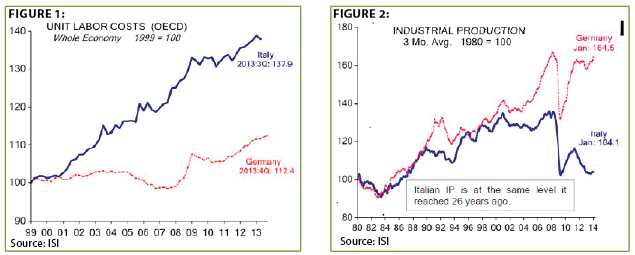

There’s always hope of an Italian growth boom, but given that the euro remains dramatically overvalued in their case (as well as for most of Europe, ex-Germany), the below conditions, as highlighted in last week’s EVA, are not likely to improve, despite an energetic new prime minister. (See Figures 1 and 2)

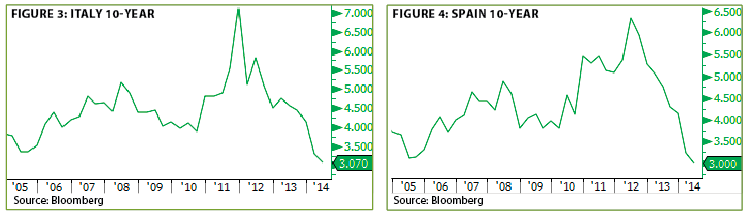

Thus, with an eventual default, at least for external and/or private sector creditors, looking highly probable, you would, once again, rationally conclude that Italy should be forced to pay very dearly to borrow money. Yet, one more time, you would be sadly mistaken. Italy is able to borrow at basically 3% for a 10-year maturity! This is essentially in line with the financing rate for the US Treasury presently. While America has a cornucopia of problems, are we really an equivalent credit risk to Italy, or, for that matter, Spain? Or Ireland? As you can see below, all three are able to issue sovereign debt at rates barely higher than the US, with Portugal not that far above those levels (even Romania recently floated 10-year debt at just 3.7%!). (See Figures 3-6; Figures 5 and 6 below)

If you’re wondering what in the (Old) world is going on, I’m right there with you!

…and the three ways they’ve managed to grow wings. As always, there are reasons why markets trade where they do; in other words, there’s always a narrative. The key in the long run is whether the story is sustainable. For example, in the late 1990s, the tale being peddled by the dotcom bulls was that, as Jeff Eulberg aptly noted last week, the internet was such a revolutionary development valuations didn’t matter. That worked wonderfully for awhile, and then you-know-what hit the proverbial fan.

In the case of “peripheral” European yields, the rationale is that with the ECB ready, willing, and able to buy the government debt of any country that gets in trouble (presumably, with the exception of Greece), then yields should be very low. As I have previously admitted, another thing I don’ t get is how ECB chief Mario Draghi’s pledge to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro could have caused such a yield compression--without his ever buying a single bond!

Consequently, this epic rally in PIIGS bonds has been totally based upon an untested promise. In fairness, I don’t question the fact that the ECB is “ready and willing” to be the bond buyer of last resort; it’s the “able” part I can’t swallow. That’s because Germany would have to go along with the scheme, and I don’t see that happening other than for token amounts.

But there is more to the story than just Mr. Draghi’s now infamous famous pledge. The other factor driving yields down is the specter of deflation. Excluding various tax hikes meant to reduce still-bloated budget deficits, consumer prices have actually declined at an annualized rate of 1.5% over the past 5 months for the eurozone as a whole. This has terrified both the ECB and the IMF (International Monetary Fund). Even Germany’s inflation-phobic central bank, colloquially known as the Buba, appears to be alarmed.

A key reason for these intense fears is the very plausible possibility the Continent is following Japan into an extended episode of intermittent deflation and economic stagnation. Undoubtedly, this is the last thing a persistently growth-challenged Europe needs right now.

And there is at least one more explanation for these seemingly crazy-low financing rates for such questionable credits: Animal spirits. This was John Maynard Keynes’ old moniker for investor risk appetites. When they are voracious, as is the case today, even dodgy borrowers can borrow on thrifty terms.

There you have a trifecta of reasons to explain how the former PIIGS (I would question the “former” qualifier) can float like helium-infused pigs and also float tens of billions of bonds at US Treasury note-type yields. But, as mentioned above, are these factors sustainable?

If you suspect my answer is no, you are definitely paying attention, although I wouldn’t blow off the notion of the Japanization of Europe. But, when it comes to the ECB being able to continue bluffing markets, or that investors’ thirst for risky yields will remain forever insatiable, I definitely am in the long-term disbeliever camp.

Therefore, it’s perhaps a good idea to consider what might happen should financing costs for countries like Greece, Italy, and Spain begin to reflect their true credit risk.

Twilight of the (central bank) gods. Perhaps I’ve become too cynical as I approach the big 6-0, but I can’t help but feel that we are going through the terminal phase of the “Era of Central Bank Omnipotence.” To give credit where credit is due (and where it has been created by the trillions!), the world’s most powerful central banks have unquestionably saved the system from multiple existential threats.

Lehman’s failure, the near-death-experience by AIG, Greece’s de facto default, a veritable bank run on all of southern Europe, and Japan’s twenty-year fling with deflation, required extreme intervention on the part of the Fed, the ECB, and the Bank of Japan. In all three cases, these institutions were faced with governments incapable of making the necessary structural reforms, so they did the only thing they knew how to do: Flood the system with trillions of dollars. As noted, the ECB also threw down the verbal gauntlet about saving the euro at any cost and, at least thus far, all these gambits have worked.

However, an essential element in all of this, that may not get the attention it deserves, is the willingness of markets to go along with the program. For example, in Japan, it is vital that big bond investors continue to be content to hold 10-year sovereign bonds at 0.7% yields (please note the zero decimal in front of the 7!) at the same time that the government is frantically striving to create at least 2% inflation. A sharp run up in Japanese bond rates would pose enormous problems for a government that is even more in hock than Greece, as hard as that is to believe (though, admittedly, to its own citizens).

Similarly, the aforementioned conundrum of 3% type yields on bonds from Italy and Spain, and a mere 6% on default-happy Greece, requires investors to continue to trust in the narrative of the ECB’s unlimited firepower.

In the US, the Fed has gone all-in on the “wealth effect”; i.e., driving asset prices up in the hope that consumers spend freely (despite voluminous research that it doesn’t work, including seminal studies on this topic by the late, great Milton Friedman).

But, what happens if the major holders of Japanese bonds, like the $1.25 trillion Government Pension Investment Fund, decide they have a fiduciary responsibility to their underlying investors and that locking into a negative yield is not in their best interest? Or if those buying Italian debt at 3% realize they are about to get “Greeced”? (Not nearly as pleasant as being “greased” in the sense that so many Greek officials are on a regular basis.)

Or if the stock market in the US decides to undergo a much overdue correction, causing even a fleeting crisis of confidence? Candidly, there are a number of pieces that need to continue falling into their precise places if this whole charade is going to continue playing out as elegantly as that old Cary Grant-Audrey Hepburn movie by the same name.

Another thing I don’t get is the abiding and pervasive belief in the “Great Deleveraging.” Admittedly, there’s been some debt pay-down in the private sectors (mostly, as one astute client pointed out to me last week, due to a plethora of underwater US homeowners doing the Greece to their lenders, aka, jingle mail). But the stark reality is that globally it hasn’t happened. In fact, total credit instruments outstanding are now around $230 trillion vs $175 trillion in 2007. Call me pig-headed (not PIIG-headed), but that doesn’t sound like deleveraging to me.

The connection with this factoid and the number of distressed counties able to borrow at low rates is that once those financing costs begin to normalize, the pain will be intense based on the even more staggering amount of outstanding debt in existence today. This definitely has the potential to upset the current state of investor complacency and reckless risk acceptance. And you don’t need much more evidence of both of those attitudes than to reflect on the ability of the above counties to borrow at such low rates (to add another example to this long list, how about France being able to float 10-year government debt at under 2%?!!).

Accordingly, I think those who say that markets aren’t overheated are wearing the Fed’s old rose-colored glasses. Past EVAs repeatedly attacked the zany valuations of the go-go, mo-mo (momentum) names like Amazon, Tesla and Netflix, and those stocks have come under serious pressure this year. The same is true of another of our repeatedly disliked areas, small cap stocks. But, although they’ve pulled back sharply, they continue to trade at highly inflated prices.

Warren Buffett has often said that wise investors should focus on what will happen not when it will happen. I’m the first to concede I don’t know when this latest era of overpaying for a wide range of securities, almost totally a function of central banks seeking to drive asset prices up to absurd valuations to create pseudo prosperity, will meet its maker. However, I am totally confident about what the endgame will look like—pretty similar to what it was for tech investors in the late ‘90s and real estate speculators in 2007. This time is not different, as even those who control the keys to the world’s print presses are destined to learn.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This report is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any securities mentioned herein. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. All of the recommendations and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions as of the date of this presentation and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Information contained in this report has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, Evergreen Capital Management LLC makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness, except with respect to the Disclosure Section of the report. Any opinions expressed herein reflect our judgment as of the date of the materials and are subject to change without notice. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments or strategies to particular clients. Investors must make their own investment decisions based on their financial situations and investment objectives.