“Awesome! I always wondered what it was like to live during the times of the Civil War, Spanish Flu, Great Depression, Civil Rights Movement, Watergate, and the Dust Bowl. Not all at once, mind you, but ya know, ‘beggars/choosers” and all.”

– Tweeter Juh-G, as quoted by John Mauldin in his June 26th, 2020 newsletter.

Long-time EVA readers may recall the legendary John Mauldin was my inspiration for starting this newsletter back during the housing bubble days of 2005. In fact, the inaugural EVA edition was almost exactly 15 years, and about $15 trillion of Federal debt, ago. John is one of the most popular and enduring financial newsletter writers around and, as these pages have often admitted, his work was a key factor in why I became convinced the mortgage mania back then was a disaster in the making.

To be totally candid, as bad as I thought that situation was going to turn out, in reality, it was far worse than I feared. John would likely admit the same thing. Lately, I’ve been having a déjà vu all over again experience related to my COVID warnings in February of this year. Never in my wildest nightmares dreams did I anticipate the apocalypse it has become. Like most humans, I find safety in the past – and perhaps that’s why I chose one of John’s recent missives to run as this month’s Guest EVA.

One thing you may notice as you read this issue is that he is picking up on the overarching theme of the book I wrote in real-time over the last two-and-a-half years that we published as a monthly EVA series, “Bubble 3.0”. The sub-title was, and still is, “How Central Banks Created the Next Financial Crisis”. As I’ve conceded, and is obviously true, COVID was the precipitating cause of our current calamity. However, Fed policies, along with those of its now not-so-rich country counterparts, rendered financial and economic systems highly vulnerable to an unexpected shock. Something was going to pull down the façade of debt and fake money-driven prosperity; the virus crisis just happened to be the catalyst – albeit an incredibly effective one.

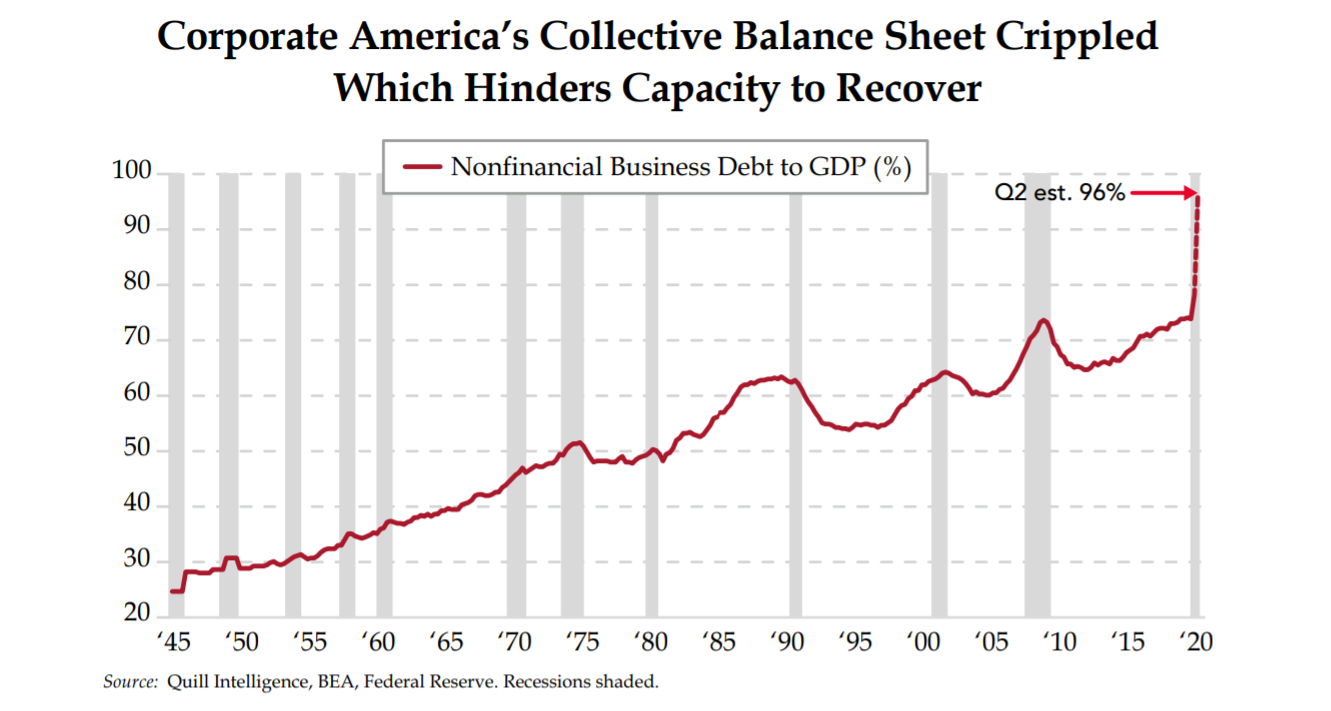

A classic example of this was the highly leveraged status of US corporations leading up to the COVID collapse, a situation this newsletter railed about for years. Per the chart below from John’s and my mutual friend Danielle DiMartino Booth, you can see how dangerous debt levels were for Corporate America even before the global pandemic and economic collapse.

Interestingly, and along these lines, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the official determiner of recession starting and ending points, recently declared the recession started in February; i.e., this was before the COVID-caused lock-downs. This news came out in early June but attracted scant media attention. However, it again shows the vulnerability of the US economy this past winter, despite the hundreds of billions the Fed was already manufacturing (a process that started last September, well before COVID infected its first victim). And, as numerous EVAs pointed out during 2019, there was already a US profits and industrial recession even before 2020 began.

John also covers the topic of debt monetization, which is a fancy way of saying that the Fed is buying the Federal government’s debt with their manufactured trillions (literally from their magical money machine). In my mind, this is THE biggest development of the COVID era, at least from an economic standpoint. If we weren’t so desensitized by a plethora of shocking developments, we would be appalled that the world’s dominant superpower (for now) is resorting to such desperate measures.

Finally, John quotes famed demographer Neil Howe, whose work we highlighted in a Guest EVA back in early June. Like me, Neil is expecting a rocky decade up ahead. My expectation is that it’s going to look a lot like the 1970s, which was very tough on both stocks and bonds, as I’ve opined before. Actually, I hope it’s not worse. However, given the absurd valuations of myriad allegedly high-growth US companies, and with treasury bonds yielding next to nothing, I don’t see how negative returns, after the impact of inflation, are avoidable, as was the case in the 1970s. The good news is that it was a fantastic decade for hard assets. Investors who anticipated the dominant trends at the time did just fine. To that point, you may have noticed gold and silver have been sniffing out this new era of debt monetization.

As John notes, we’ll get through this tribulation, but likely with a massive debt reset—basically, a debt jubilee or forgiveness. (See “Bubble 3.0: End Game (Part II)”.) Then, hopefully, our country and the world can move forward without this increasingly crushing burden.

Some readers might be asking themselves, just how crushing of a debt burden are we facing?

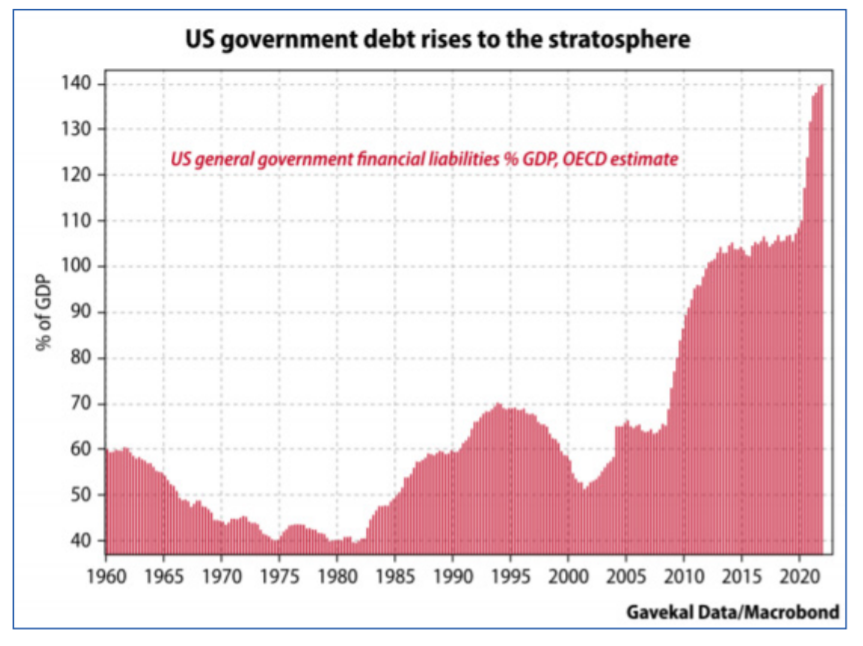

Well, we were originally planning on publishing a very interesting read from one of our long-time friends and author of Things That Make You Go Hmmm, Grant Williams, on the subject. And, although we opted to share John Mauldin’s equally timely letter instead, readers who are interested in reading Grant’s work on this subject can subscribe to his newsletter here. (Those who search extra hard can even find a special shout-out to Evergreen GaveKal on page 47 of his missive “Gradually, Then Suddenly,” where he highlights the ungodly rise of US government debt-to-GPD shown in the chart below).

It goes without saying, though I will do so anyway, that there will be big winners and big losers from this paradigm shift. The latter might be forced to reprise that old line from another past decade, the 1930s: “Brother, can you paradigm?”

We are on the horns of a dilemma, caught between the Scylla and Charybdis, a rock and a hard place, the devil and the deep blue sea, the anvil and the hammer. The walls are closing in. We’re in a tight spot.

All those metaphors (I could list more but will spare you) fit the present economic situation (some are now calling the omni-crisis) and I think will also describe the 2020s.

Thanks to forces that were already in motion and coronavirus as the trigger, we are out of good choices. Every possible fiscal, monetary, social, and political policy will have negative effects, some larger than others. All we can do is choose who gets hurt and in what ways. That’s a bad place to be, but it’s where we are.

This week’s Federal Reserve policy meeting gave yet more evidence that no one, even the mightiest central banks, can restore the growth to which we have grown accustomed. The best the Fed can do is (sorry to use more metaphors) keep the life raft afloat by continuing what they have done for decades.

And that’s the problem. In their effort to improve things/prevent pain, Fed officials past and present financialized the economy. That, along with more unintended consequences from government debt and regulatory interventions (all well-intentioned, you understand) brought us to where we are today. We can’t walk it back without a great deal of pain no one wants to take, including your humble analyst.

So we stumble into the life raft. That’s not nothing. As long as we’re afloat, we still have hope. We can do things that may help. But it’s not ideal.

We didn’t have to be here. But, like I said, we are here. The next question is where are we going? Today we’ll explore that question.

Wordy Intellectuals

In his 1999 book, In the Beginning… Was the Command Line, dystopian sci-fi and cyberpunk author Neal Stephenson (one of my favorites) said this:

“During this century, intellectualism failed, and everyone knows it. In places like Russia and Germany, the common people agreed to loosen their grip on traditional folkways, mores, and religion, and let the intellectuals run with the ball, and they screwed everything up and turned the century into an abattoir.

“Those wordy intellectuals used to be merely tedious; now they seem kind of dangerous as well. We Americans are the only ones who didn’t get creamed at some point during all of this. We are free and prosperous because we have inherited political and value systems fabricated by a particular set of eighteenth-century intellectuals who happened to get it right. But we have lost touch with those intellectuals.”

Now, given current events, I should note those eighteenth-century intellectuals who founded the US didn’t get everything right. They compromised with slavery, although some were vigorous opponents. They thought women shouldn’t own property or vote. Most states required either the outright ownership of land or a certain net worth in order for white males to vote. We are still struggling to escape those legacies, but the Framers broke from the prevailing wisdom of their time in other beneficial ways. They were true revolutionaries for their times, and true intellectuals.

Far be it from me to say that intellectualism itself is bad. Pursuing knowledge and truth is important. The division of labor principle says we all benefit when some people make it their specialty. Problems arise when those people grow too enamored of their knowledge, become convinced of their own superiority, and seek to force their ideas on everyone else. Thinking deep expertise in one area means expertise in many areas is how you get unintended consequences.

The latest example is in central banks, and especially the US Federal Reserve. The Board of Governors and the regional Fed banks employ hundreds, maybe thousands, of highly educated economists. They do some useful work. They also develop ideas that may seem reasonable from their lofty perches, but unleash chaos they don’t even see, even after the fact.

It’s not just that central banks interfere with markets. They do that by their very existence. But they go even further by making capital flow inefficiently. Back in the 1950s, Joseph Schumpeter talked about capitalism’s “creative destruction.” As economies grow and develop, the old ways have to step aside as better innovations appear. Automobiles couldn’t achieve their full potential as long as horses were still in the streets, along with 2.5 million pounds of horse manure a day in NYC.

The economy needed horses to step aside. The horse industry correctly saw a threat to its livelihood. This delayed the transition but couldn’t stop it. That’s creative destruction.

Central banks have always interfered in this process, appropriately so at times, but this year they’re pushing their thumb on the scale (sorry, another metaphor) by actively subsidizing businesses and entire industries via bond purchases and other such programs.

That’s a problem in multiple ways but particularly for investors. My friend Jim Bianco stated it well in a Bloomberg TV appearance this week.

"If we're not allowing capital to flow away from bad ideas and towards good ideas and we're impeding that process with a price-insensitive buyer then we should expect that the traditional ways we invest won't work as well..."

But it doesn’t end there. The Fed’s intellectuals are now headed toward the kind of “yield curve control” (YCC) Japan has had for years. The main result has been to snuff out Japan’s bond market. Nominally, they still have one, but it doesn’t matter because the Bank of Japan simply dictates the “market” rate.

Now, Japan is doing relatively well. Its economy hasn’t collapsed. Maybe YCC will eventually achieve its goals. But it hasn’t happened yet, and I see little evidence it ever will. Meanwhile, their debt keeps growing and their economy doesn’t.

But the broader point remains. It is not “capitalism” in any meaningful sense when people and businesses get bailed out of their mistakes. Repeatedly. Companies that should have failed become zombies, consuming resources and preventing innovation. The result is slow growth and inefficient capital allocation.

It gets worse. With interest rates arbitrarily low, it is now cheaper for large companies to buy their competition than to compete. Corporate debt rose from 250% of GDP to over 300%* in the last 20 years. Many (not all) companies have mortgaged the future for stock buybacks and other financial manipulations, rewarding executives and shareholders in the short term. This is what I mean by financialization.

Financialization has short-circuited Schumpeter’s creative destruction process. Cheap money has rewarded those who have access to it and sharpened the divide between the haves and have-nots. Unintended, but very real.

Ah, but were companies harmed by coronavirus guilty of mistakes or just bad luck? Some of both. If you are smart enough to manage a large business, you should know the economy has cycles. You should know how to prepare for them: have cash reserves, use debt wisely, and so on. If you instead leveraged up on share buybacks in order to pad your own compensation, then yes, you made a mistake and you should pay for it. That is how capitalism works. Government’s role is to protect the vulnerable, not save the elites.

To use another metaphor, extinguishing every small brush fire lets undergrowth accumulate. Eventually, something ignites it and we have an inferno. That is where we are now. COVID-19 lit the fuel the Fed’s intellectuals protected for so long. We are seeing the results with a recession/depression OECD is calling (correctly, I think) the worst in almost a century.

But the Fed isn’t the only culprit.

*EG note: In our opinion, John may have meant to say total US debt-to-GDP versus just corporate debt.

Rocky Rollouts

Even before the pandemic, central bank chiefs were telling their governments, in effect, “We’re running out of bullets over here.” They were correctly recognizing that monetary tools, while powerful, can’t do everything. Fiscal authorities have to do their part, too. Tax and spending policies can accomplish things central bank policies can’t.

Fiscal policy must be executed correctly, or it will be ineffective or even make matters worse. Tax hikes during a recession, for instance, rarely help. The pandemic-related programs are even worse because political leaders, under pressure to “do something” in a crisis, designed them so hastily.

The “Paycheck Protection Program” is a good example. It sounded good in theory: Small businesses could get government loans, all or part of which would be forgiven if they spent it on payroll and certain other expenses. It was supposed to keep people off the unemployment rolls.

Yet the very same bill also raised unemployment benefits to a level far more attractive than the salaries many workers were making. Then PPP’s rocky rollout overlooked many businesses. Congress appropriated more money, but it was too late for some. Now legislators have changed some of the main features and are talking about yet more changes, which may be good, but the instability greatly complicates planning for businesses that already have enough headaches. They can’t use the money effectively unless they know the rules, and the rules keep changing.

That’s the story of many government programs. They have worthy goals but prove less useful once implemented. Yet they still generate debt. That wouldn’t be so bad if the debt at least bought tangible public benefits. We may laugh at China’s debt, but China at least has great airports and railroads. Here, we just give away cash to favored groups, who often use it to buy unproductive goods.

John Maynard Keynes was actually right when he said governments should run surpluses in good times so they can spend more in downturns. Nowadays we just spend more, all the time, and even more in the occasional rough stretches.

The result: more debt, staggering amounts of it, that must at some point be repaid. Debt is future consumption brought forward. You balance the scale by spending less in the future, which is why we talk about “burdening our grandchildren” with debt. Unproductive debt reduces future growth, which is yet another way our children pay for our spending today.

It has reached the point where these future generations can’t bear much more. Our grandchildren have their hands full. So do our children. Which means, if we want to keep spending, we must pay for it ourselves. Which raises the question, not just in the US but all over the developed world, with what?

The answer seems to be with ever-rising debt and increasingly with monetization by the central banks.

The Devil and the Deep Blue Sea

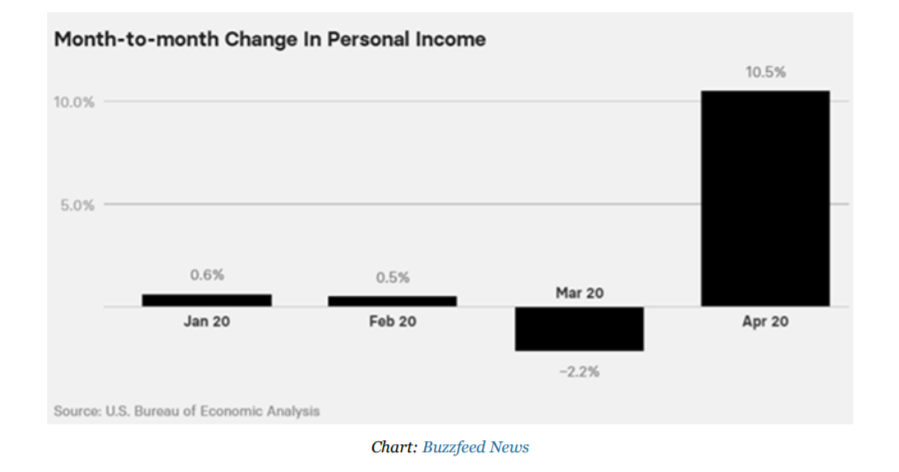

Let’s look at a few facts. Some 40 million Americans lost their jobs in the past few months. There’ve been temporary bans on home foreclosures, with many mortgages given six-month extensions, extensions on student loans, rental evictions have been temporarily banned. An extra $600-a-month federal unemployment benefit helped replace the lost income for many. For some, the unemployment benefit is more than they were making prior. It actually sparked the largest monthly household income jump ever. Who knew?

Savings have actually risen to 33% of income, at least for the short term, which of course is the highest ever on record. All this is the result of legislation passed over the last two months and multiple trillions of dollars spent. According to the US Debt Clock, total US government debt is now $26 trillion, plus $3.2 trillion state and local debt. Federal debt will almost certainly reach $30 trillion in 2021 from a combination of increased spending and reduced revenues.

Most of those temporary benefits will expire soon. Federal unemployment goes away July 31. The various loan extensions/foreclosures/evictions also begin to come back in the third quarter. The theory is that the economy will be back, everyone will have their jobs, and that life can go on.

Except no one really believes that theory. Maybe, with luck, we can be 90% back. But that is still a major recession from where we were in 2019. The OECD and others say it will take five years or more to fully recover. It is easy to imagine 10% unemployment at the beginning of next year. A lot of small business just won’t come back. Some large businesses, too.

Take Hertz. Please. The company now plans to do a stock offering even while it is filing bankruptcy. I read this morning that disclosure documents say that the stock will “ultimately be worthless.” (H/T Peter Boockvar) However, management would be derelict if they didn’t take advantage of the insane stock price.

Hertz will survive. Someone will buy it and with a bankruptcy-reduced debt structure it should do well. It will just be smaller, with fewer employees. That story will be repeated often over the next few years. Same song, different company.

Congress is working on yet more multi-trillion-dollar bailouts to try to keep things moving along. I think it is safe to assume Washington will do everything possible to minimize pain prior to the November election. After that, all bets are off.

So, we are headed toward a really awkward moment. At some point in the future, probably post-election, some combination of people are not going to get what they think they should, and whoever it is won’t be happy. How is that going to work? Not well, I’m afraid.

Fourth Turning

Now consider where we are with the pandemic. Conditions are improving in Europe and Asia. New Zealand seems to have eradicated the virus after weeks with no new cases. In the US, hard-hit New York and New Jersey are on the mend. Cases are rising in some other states, which was expected as lockdowns ended. Now the challenge is to minimize the spread.

At the same time, the pandemic is just getting started in Latin America and Africa. And even in the places where it is under control, economic conditions are not remotely back to normal. Many are still staying home (and rightly so, if they are in a vulnerable group).

It is unclear when large events can return. That means the airline seats, hotel rooms, restaurant meals, and other things associated with conventions and travel will also remain unsold. That, alone, adds up to a major recession. And this is assuming the virus doesn’t resurge and we get a vaccine fairly soon.

That leaves us in a bad spot, just as Neil Howe’s Fourth Turning period approaches its peak in the coming decade. We are at the point in his generational cycle when society’s institutions are shaken, and sometimes destroyed and replaced. George Friedman points to the latter half of the 2020s as a similar cyclical peak, for different reasons. They both agree the next decade will be highly volatile and tumultuous.

Having talked with both Neil and George, they both still see the true problems developing in the latter part of this decade. That coincides with my own concept of The Great Reset, centered around the accumulation of debt.

I have repeatedly demonstrated how large amounts of debt reduce potential GDP growth. We are now past the point of no return. I know Paul Krugman and others say it doesn’t matter, but the data says otherwise.

The world is now run by a cadre of intellectuals (call them elites or whatever) who have theories about how the world should work and are intent on implementing those theories. We will explore it further in the future, but these theories will aggravate the economic divide. Raising taxes on “the rich” won’t have the beneficial results they expect. We’re way past that point.

I don’t see how we get through this without significant pain. I also don’t know how to reconcile that with present political structures. People don’t typically vote to bring pain on themselves, nor do they react kindly when they perceive the winner wants to hurt them.

At the same time, I’m still hopeful. We have been through harsh recessions, pandemics, and political polarization before. We have seen Fourth Turnings before. They aren’t fun. Yet we always get through them. Not without losses, both financial and personal, but the world survives, society rebuilds, and life goes on.

Seriously, you can look at every similar past cycle and if all you focus on is the pain, you miss the incredible businesses and opportunities that developed at the same time. That’s what I expect this time, too.

The Stumble-Through Economy

I coined the term “The Muddle-Through Economy” in the early 2000s to describe what I saw as the economy of the next decade. I kept repeating it this last decade. Sadly, it is time to retire that term. I don’t think we muddle through in the 2020s. It will be more like Stumble Through.

By that I mean the market volatility, political polarization, global discord, and transformational technology and business changes will at times seem overwhelming. Governments will change their priorities with each election cycle. Continuity will become a thing of the past. We will long for the good old days of 2% growth.

But the point is that we’ll get through. The world won’t end, and if you pay attention, there will be opportunities all around. But those are topics for later letters. Stay tuned. And by the way, you really should follow me on Twitter.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.