“Doing well is the result of doing good. That’s what capitalism is all about.”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

“Capitalism has not always existed in the world and will not always exist in the world.”

– Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

“Communism can’t survive the captivating allure of capitalism.”

– Rand Paul

Capitalism is an economic system where private individuals or corporations own capital goods and/or provide services. In a market economy, the production of these goods and services is based on supply and demand, rather than through planning by a central government. While the system is not without fault, its principles have long-formed the foundation upon which the “American dream” was built.

Over the last several years, this dream has come under increasing attack, with many questioning its ability to provide equal opportunity to all corners of the socioeconomic and demographic spheres. The United States seems to be ground zero for these discussions, especially as an already contentious federal election is fast-approaching.

In this week’s newsletter, Evergreen’s partner Louis-Vincent Gave makes the case that, historically, there have been three waves that have driven capitalism forward. He argues that each of these waves tend to dominate markets for a short period before ceding to another force. One particular example he homes in on is oil, which led markets at the turn of the last decade when fears of “peak oil” persisted. However, as the waves of capitalism have turned over the past ten years, technology stocks are now in force, while massive sums of capital have left energy stocks, leading to numerous mergers and bankruptcies. It’s our belief that should a far-left-leaning candidate win the US presidency next November and ban fracking (as has been proposed), natural gas prices could quadruple, and oil prices could double or triple. The beneficiaries of such a scenario will likely be overseas while the economic fall-out could be devastating. Thus, as Louis also concludes, it’s likely that the next big wave of capitalism will not come from within the United States but rather in emerging markets in South Asia, South East Asia, Russia and Africa. We are also becoming increasingly fond of Canada as a refuge for US investors seeking shelter from what may be an escalating war on capitalism in America.

Historically, three waves have driven capitalism forward, each dominating in turn:

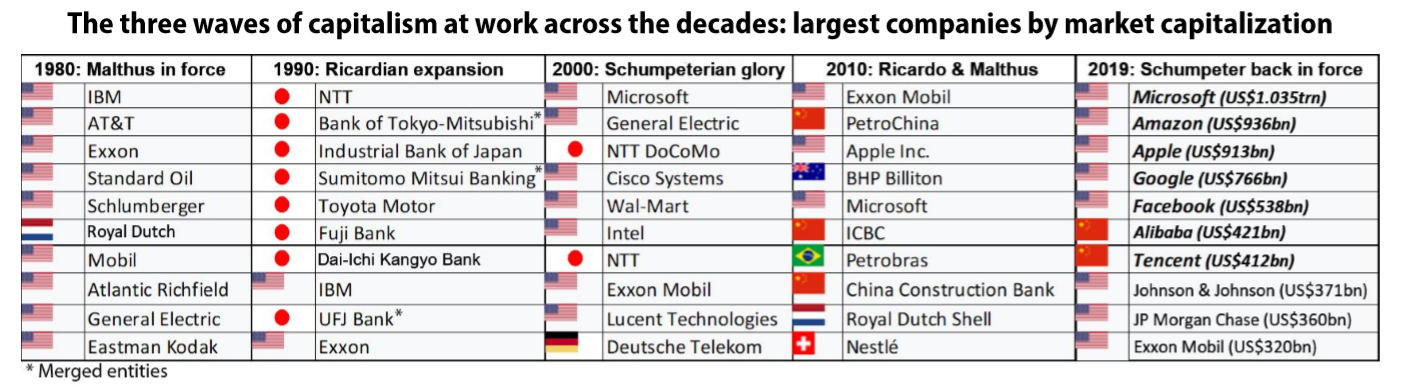

Given today’s prevailing belief that the world has now gone ex-growth, investors are currently piling into Schumpeterian plays. Not only are the top seven companies in the world by market capitalization technology plays (the first time the top seven all come from the same sector), but the sums of money flowing into venture capital funds, private equity tech funds and the like over the last decade dwarf the amounts invested over the previous 30 years.

What will the returns on all this invested capital look like? To the casual observer, it might seem that:

Of course, capital destruction is nothing new. Take the oil industry as an example: 15 years ago, one of the dominant driving forces of capitalism was the Malthusian concept that there “wouldn’t be enough to go around for everyone”. Not enough copper. Not enough wheat. And most of all, not enough oil. In the quarters that preceded the Lehman Crisis, but also in the months that followed, most investors firmly believed in the danger of “peak oil,” and feared a “commodity super-cycle.”

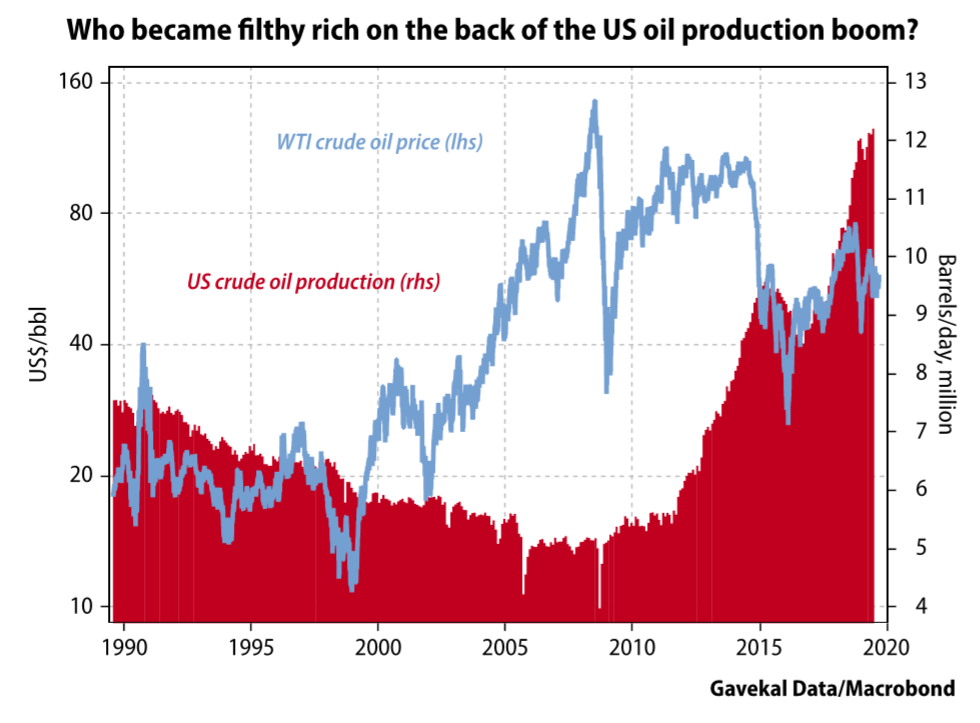

Capital poured into the energy-extracting industries: high-yield debt was issued, and private equity and VC funds were raised. At the time, the idea that the US could go from producing 5mn bpd of crude oil to 12.5mn bpd would have struck most investors as highly fanciful. At the start of 2006, US producers were painfully extracting 5mn bpd, and their oil sold for roughly US$60/bbl. Fast forward to today and US oil production now stands above 12mn bpd, and the price still hovers around US$60/bbl. Therefore, you might have expected US oil producers to have become filthy rich over the last decade or so. They are producing more than twice as much oil and continue to sell at roughly the same price. So, US oil stocks must have been the best investment ever, right?

Wrong! Take the US oil services sector. You might have thought it would be a big beneficiary of the massive capital inflows into exploration and production, and of the consequent surge in production. Yet, as the left hand chart overleaf shows, today stock prices in the sector are scarcely higher than the lows seen in the aftermath of the Asian crisis—a time when WTI crude touched US$10.80/bbl, and when The Economist came out with its legendary March 1999 “Drowning in oil” cover.

Note that the left-hand chart above is in absolute terms. As the right-hand chart shows, in relative terms, over the last decade the oil service sector index has shed a cool -91.3% of its value relative to the S&P 500!

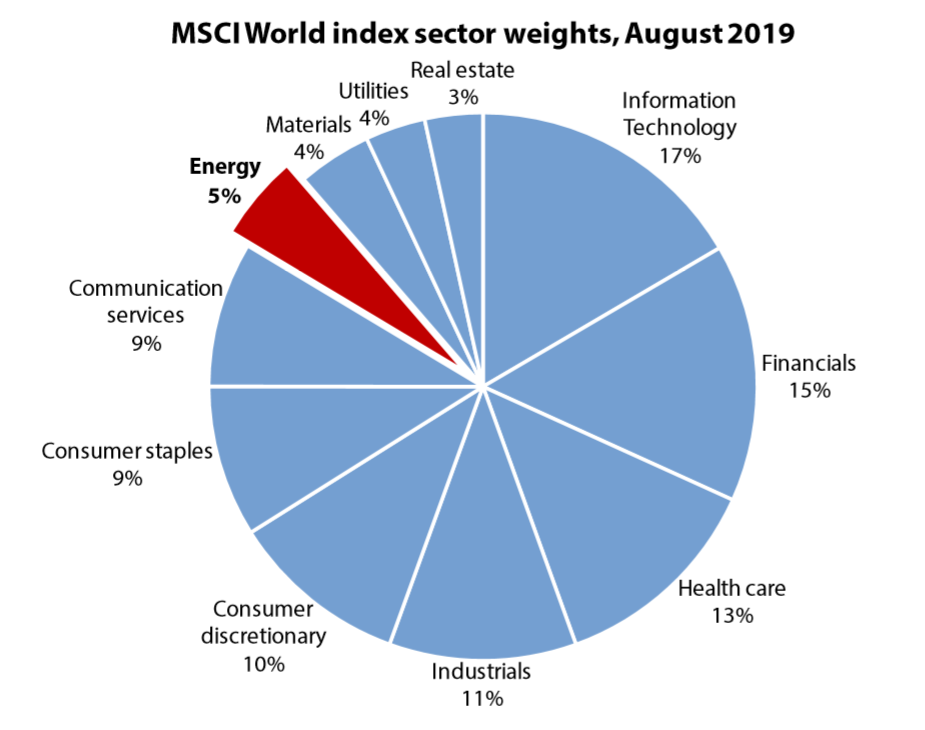

You could say this is what the aftermath of a bubble looks like. Yet a decade ago, who would have thought that with an oil price that has remained broadly flat, and with production that went through the roof, the weight of energy in the S&P 500 or the MSCI World index would fall to all-time lows of around 5% of total outstanding market capitalization?

In short, a decade or so ago, investors poured capital into the US energy industry in the hope of (literally) striking oil. Oil was found, all right. But investors were left a whole lot poorer for it!

Back in 2006-10, an observer who had been told of the coming oil production boom in the Permian or the Bakken might have been tempted to load up on West Texas or North Dakota real estate. Or maybe he or she would have assumed that the hit television shows of the coming years would have featured rapacious oil tycoons plotting each others’ downfall, drinking themselves silly, and fending off (or not) the advances of blonde man-eaters, as in Dallas or Dynasty in the early 1980s. Instead, we got shows like Silicon Valley, following the lives of bland San Francisco Peninsula computer geeks: no murders, no drinking, no sibling rivalries, no affairs; just plot lines about finishing lines of codes before deadline and who gets to own what copyright.

What conclusions should we draw from this?

This “iron-rule” of capitalism may help to explain why it is so hard for any of capitalism’s three big waves to last for much longer than a decade, as shown by the table above.

This brings me back to today. As I write, it seems the general consensus among investors is that the modern world is first and foremost characterized by weak, and falling, economic growth. And behind this weak growth there are a number of structural factors that are unlikely to change any time soon: aging and demographic decline in the West, over-leveraged consumers highly dependent on sky-high property prices, a change in the zeitgeist towards less showy consumption and environmental responsibility, etc. From here, the view among investors is that they should deploy their capital in the one area where they know they will find growth: the Schumpeterian quest for greater productivity gains.

But is this view forward-thinking, or are investors looking backwards?

No doubt, the tech sector has been very strong at raising capital over the past decade or so—just as the energy sector raised billions in the days before and after the Lehman crisis. The question today is whether—for all the capital raised—returns from the technology sector will rise from here or fall. Most stocks seem to be priced for a continued rise in returns. But a rise in returns on invested capital, just as the amount of invested capital has surged, would defy all historical precedents.

And if returns from the tech sector fall from here, the question will then becomes: Where will the growth come from over the next decade?

Perhaps the best bet is that investors will once again become excited about deploying capital across the expanding borders of capitalism—in emerging markets. This may make sense, if only because as things stand emerging markets are actually priced to deliver at least modestly attractive returns. So perhaps the next big wave will be Ricardian, playing out across South Asia, South East Asia, Russia and Africa.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.