“Whenever I hear numbers like this, I look back to my childhood growing up in Hungary, where…[the] value of money meant nothing. I’m very worried this is an unstoppable situation because the longer the Fed waits, the more they will have to raise rates. So, we’re basically painting ourselves into a box, and I don’t see how we’re going to get out of it.”

– Thomas Peterffy, chairman and founder of Interactive

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

It seems as though wherever one looks, soaring prices are in the news. Everything from the rising price of lumber to oil, to housing, to food is dominating headlines. This week, key inflation data was released, and let’s just say it wasn’t pretty. The Consumer Price Index (CPI), which measures a basket of goods as well as energy and housing costs, rose 4.2% year-over-year, surpassing expectations from a Dow Jones survey that anticipated a 3.6% increase. The month-to-month gain was also much higher than expected – at 0.8% versus 0.2%. Additionally, the Producer Price Index (PPI) – another key inflation indicator – spiked 6.2% for the 12 months ended in April, which marked the largest increase since the Bureau of Labor Statistics started tracking the data in 2010. The PPI rose 0.6% month-over-month, which was twice the rate expected in a FactSet survey.

Markets were rattled by the data – as nearly everything sold off on Wednesday after CPI data was published. Markets gained back some of the losses on Thursday morning, before selling off slightly mid-day when PPI data was released. Despite these key inflation indicators signaling trouble ahead, economists and policy makers have attempted to quench fears by signaling that the rising prices are “transitory.” Federal Reserve Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic said Wednesday that he expects bouts of inflation volatility through September. And according to one government official, the White House sees this “transitory” period of inflation pressures lasting potentially through the end of the year.

This week, we are presenting musings from our partner Louis-Vincent Gave on whether there are any lurking deflationary shocks supporting the view that that the inflation readings we’re seeing are “transitory”. Given the importance of inflation on macro-economic and market conditions, we will be following up with two additional thought pieces over the next couple weeks. Next week, we will share a superb presentation from Louis Gave at John Mauldin’s 2021 Strategic Investment Conference (SIC) before hearing from Evergreen’s Chief Investment Officer, David Hay, on the subject the following week. (Sneak preview: David is seeing signs of peak inflation in many commodity prices but there’s much more to the long-term story than just temporary shortages of building supplies, semiconductors, and other key materials.)

The 1986 oil price crash, to an extent, fired the starting gun on 30 years of global deflation. As commodity prices collapsed, so did the Soviet Union, giving the West a deflationary peace dividend. By the early 1990s, Japan’s real estate and equity market busts threatened its banks. The rollout of the North American Free Trade Area and the 1995 “tequila crisis” helped make Mexico a competitive manufacturing hub. Soon after, the 1997-98 Asian crisis made producing abroad even cheaper, while China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization greatly simplified outsourcing. In 2008, the US mortgage bust spurred China to build more infrastructure, unleashing 500mn more workers into the global economy. Europe’s 2011-13 crisis caused another deflationary hit, while the US’s shale energy boom stopped oil and gas prices rising. So today, as inflation expectations move toward generational highs, a relevant question is: where might the next deflationary shock come from?

Europe. If vaccine rollouts let Europeans vacation freely this summer, it is unlikely to spur deflationary forces. The effect should be steeper eurozone yield curves, outperformance by financials and a firmer euro. Yet, if Europeans are told to stay home, another deflationary eurozone crisis could still ensue. Citizens deprived of a vacation may register their protest at the ballot box or, more likely, on the streets. For this reason, the odds are high that Europe re-opens, just as last year’s large fiscal stimulus gets rolled out. We should thus assume that—for now at least—Europe will not be a deflationary black hole.

Commodities. With Europeans set to hit the beach and Americans looking to crank up the vehicle miles, energy prices should stay well bid. And as about a third of the cost of producing commodities is attributable to energy, the broader complex is unlikely to provide any kind of deflationary shock in the near future.

The US dollar. As big projects in emerging economies are mostly funded in US dollars, any strengthening of the unit reduces their growth and depresses commodity prices. So, could a rising dollar unleash deflationary forces? For now, the US currency is making lower highs and lower lows, in spite of higher yields. This is perhaps not surprising, as the Federal Reserve has promised to add US$120bn of fresh dollars to the global system each month. Given such generosity, the threat of a US dollar short squeeze has now greatly receded. Hence, the dollar seems unlikely to be a deflationary force in the near future.

The renminbi. With so much production capacity centered in China, the renminbi’s value is vital for manufacturers. When it is weak, few Western industrial firms can compete with China but when strong, foreign producers can expand margins and/or compete on price. Whether viewed on a three-year, five-year or 10-year basis, the renminbi has been the world’s best-performing major currency on a total return basis, which shows that, structurally, there is little appetite in Beijing for a devaluation. Moreover, as China’s trade surplus hits new highs and the authorities there tighten both fiscal and monetary policies, there seems little reason, cyclically, for this to happen.

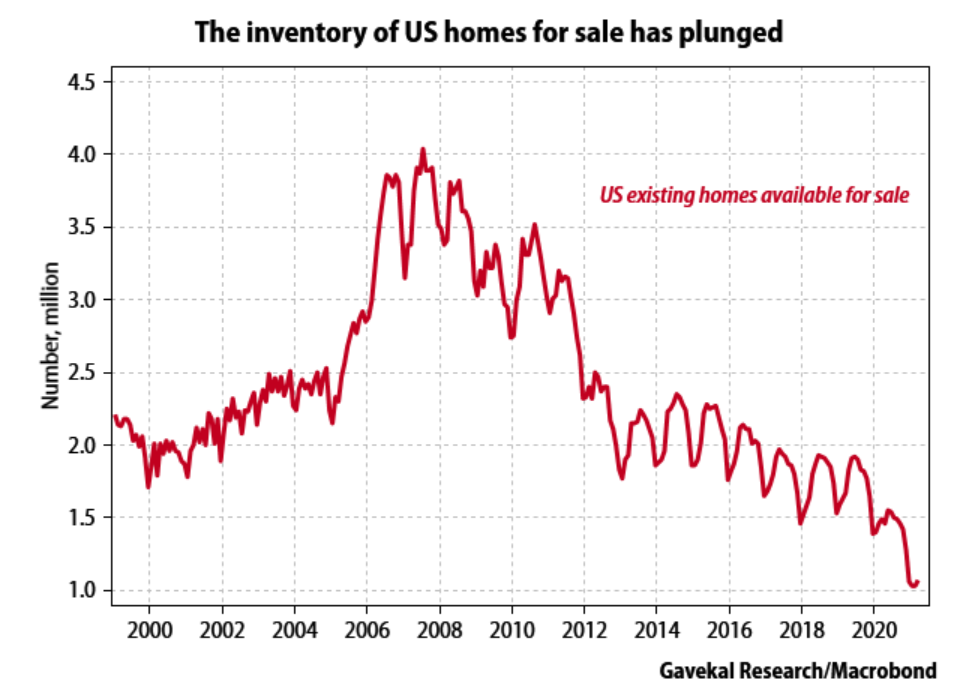

US real estate. Homes are getting expensive, with median prices relative to incomes near the highs seen in 2006-07. The difference now is low supply as the stock of existing homes available for sale is at an all time low. Add into the mix the soaring cost of skilled labor and surging prices for building materials and it is hard to see why US real estate prices should crater anytime soon.

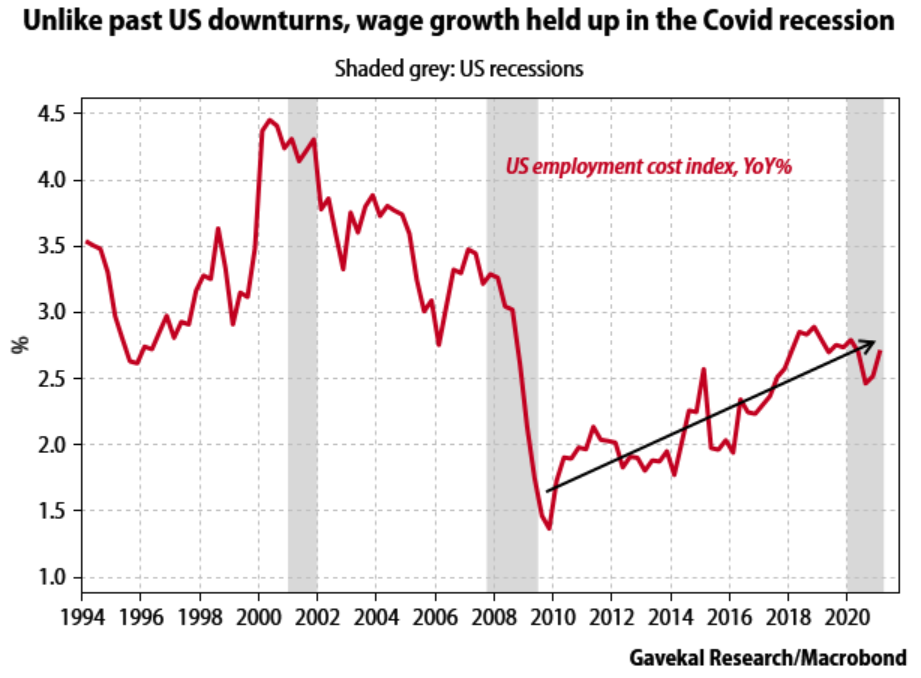

Putting it all together, in the coming few years those “usual suspects” that previously unleashed deflation are now more likely to raise the inflationary temperature. Hence, if deflationary forces are going to carry the day, there will need to be impressive productivity gains. Somewhere in the system, someone will have to produce a whole lot more, with a whole lot less. But is this likely given the following trends that have been covered in recent Gavekal reports?

This leaves us in the situation of seeing the price of everything from meat, corn, gasoline and lumber to shipping rates rise without a clear countervailing deflationary force. In an environment of rising government intervention, expanded public hand-outs, higher corporate taxes and more protectionism (and that is just the US!), it is possible that a surge in productivity provides an offset to the growing inflationary wind. But like an Elizabeth Taylor marriage, this seems to represent the triumph of hope over experience.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.