“Your success in investing will depend in part on your character and guts and in part on your ability to realize, at the height of ebullience and the depth of despair alike, that this too, shall pass.”

– Jack Bogle

At the beginning of the year, it seemed almost unfathomable to those in the West that the world would change as drastically as it did at the end of the first quarter. In fact, as recently as the end of February when we published “The Virus Heard ‘Round the World,” we received some serious blowback on our alarmist message that Covid-19 was a serious threat to people, companies, and markets. One reader even commented, “I’m no bull, but I can’t buy the Coronavirus being a serious matter. I think you cherry-picked your sources to be pessimistic.”

Just over a month later, the number of confirmed Covid-19 cases has officially – and unceremoniously – surpassed the million-person mark globally. When we published our missive five weeks ago, the pandemic was concentrated in Asia and Europe, with only a very small sprinkling of cases in the USA. Today, the United States leads the globe in the number of reported cases by a pretty unhealthy healthy margin. The point of this quick look-back is not to gloat that Evergreen was ahead of the curve in our understanding of the impact of Covid-19. Rather, it serves as a very important reminder of how quickly this pandemic has evolved – and could evolve further.

While there’s plenty of uncertainty around the long-term impact of Covid-19, what’s clear about the pandemic is that it’s not just attacking people’s physical health. It’s also trickling cascading into the financial, emotional, and mental health of people everywhere.

As such, the question “who will win the war on Covid-19” might seem tone-deaf at face-value. After all, does anybody really “win” a war? You may have heard the old saying that when it comes to war it’s not who is right but who is left! However, the question is a very important one because in the midst of incredible uncertainty and fear is when opportunity presents itself. One of Warren Buffett’s most famous quotes is, “Be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.” Two weeks ago, when markets were in the midst of an unprecedented (and fear-inducing) slide, we argued that it was time to buy depressed securities. Within a week, the Dow roared back into bull territory.

Again, the point is not to gloat in any short-term successes, particularly since we are concerned that this bear market isn’t done mauling the millions of investors who allowed themselves to become over- exposed to stocks. Yet, despite our near-term worries, we’d like to relay the message that “this too shall pass” – and when “this” does, investors who sat paralyzed by fear will have wished they’d sprung into action. (To reiterate a long-standing EVA recommendation, we strongly believe investors these days should be springing into precious metals and those companies that produce gold, platinum and silver. The enormous government expenditures now occurring to win this particular war, combined with equally enormous monetary stimuli, are producing a hurricane-force tail wind for this still very neglected corner of the investment world.)

This week, we are presenting another missive by our esteemed partner, Louis-Vincent Gave, on winners that are likely to emerge following the war on Covid-19. For those anticipating a Special Edition EVA between Louis and Evergreen’s CEO, Tyler Hay, our plan is to publish that discussion in the coming weeks.

Faced with the Covid-19 pandemic, politicians in countries around the world—Sweden and Japan are among the few exceptions—have resorted to the martial rhetoric of wartime leaders, and in many cases have invoked outright wartime powers. Mass media have been mobilized to broadcast that the world is at “war” against this new plague—a total war that will permit no conscientious objectors or draft-dodgers, and which will reshape societies once victory is won. As in any total war, monetary and budgetary constraints have been thrown out of the window. The only thing that matters is victory.

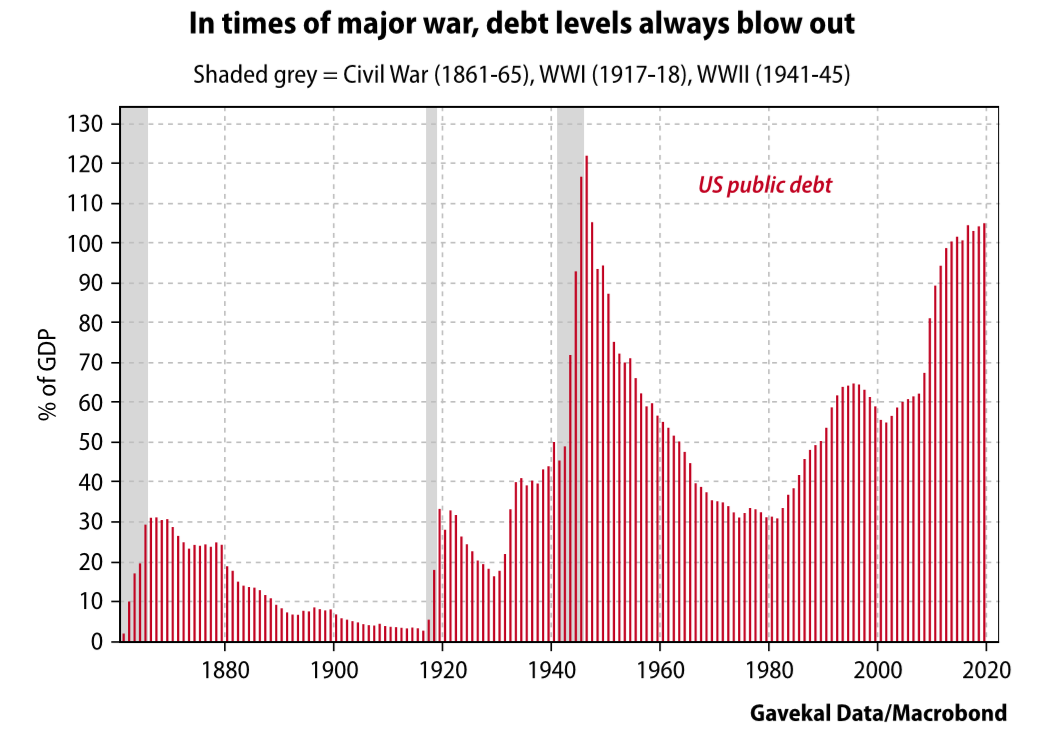

As a result, in the coming months, most countries will register new record highs in public debt and monetary aggregates. For example, take the United States, where US government debt grew to 30% of GDP during the US Civil War, shrank, leapt back to 30% in World War I, and then leapt again to 120% of GDP during World War II. Now, the coming weeks are likely to see that 120% record broken on the back of the stimulus measures already announced and the inevitable collapse in GDP.

The logic of wars is that they destroy enormous amounts of capital (check), ruin lives (check), overturn political structures—World War I saw the end of the Russian, Ottoman, German and Austro-Hungarian empires—and that someone usually ends up winning (even if it is a Pyrrhic victory). For example, at the end of the Thirty Years War, the Treaty of Westphalia enshrined France’s dominance of Europe for the following 140 years until the French Revolution.

In 1815, after Waterloo, Perfidious Albion (Evergreen note: Great Britain) emerged as the superpower that would dominate the whole world through the 19th century. And of course, the two World Wars saw Britain passing this leadership mantle to the US.

So, will the war on Covid-19 have a winner? If we accept that we live in a world with three main powers—the US, Europe, and China—then the Covid-19 war could have four potential winners: the three superpowers, plus the broad idea of “globalization”—the notion that we are all in this together and that global problems should be tackled through greater exchanges, integration and goodwill between the big three blocs. Alas, while the idea might sound nice on paper, it seems today that the world is moving rapidly away from this ideal. So, in the interest of brevity, I will discard this fourth possible “winner”. Right now, further global integration looks not so much a low probability scenario as a fevered pipe dream. This leaves three potential winners.

Europe—a Chernobyl moment

The current crisis has laid bare all of Europe’s warts. Firstly, contrary to the dreams of the Europhiles and Eurocrats, Europe simply isn’t a nation. In the 19th century, to counter Prussian racial views on the origins of the nation, the French scholar Ernest Renan argued that a nation is defined first and foremost by a “willingness to live together”. In time, this leads to the creation of a state, which assumes the role of protecting citizens against enemies, both foreign (whether by diplomatic or military means) and domestic (with a police force and the judicial system). To accomplish these “regalian” functions, the state maintains a monopoly on the legal use of violence and raises taxes in its own currency—within its own borders. And those borders are essentially just the scars of history and geography. Today, Europe, like the rest of the world, is under attack; an attack that warrants a government response. If the European Union was a nation, then the EU’s leaders would be in the vanguard of the counter-offensive. Instead, apart from a video of European Commission chief Ursula von der Leyen washing her hands while humming the Ode to Joy (the European anthem), the response of European institutions to the crisis has been deafening in its silence. This raises several questions.

With a void at the center of Europe, national governments facing economic and social Armageddon have reacted by (i) taking back control over their budgets (Fiscal Compact be damned), (ii) taking back control of their borders and (iii) taking back control of their laws (for example, by prohibiting the export of essential medical equipment, against all EU law).

This raises the question of how long it will be until one or more European governments decide to take back control of their currencies. If, as Rahm Emanuel said, you should “never let a serious crisis go to waste,” then what better time to institute a long bank holiday and reintroduce a national currency than when the national economy is in lockdown anyway, and the year is a complete economic write-off? As William Shakespeare wrote: “When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions.”

A few short weeks ago, Western pundits were asking whether the mishandling of the Covid-19 outbreak could be the Chinese Communist Party’s “Chernobyl moment”—the moment when the man and woman in the street lose confidence in their governing institutions. Forget China. It is far more likely to be Europe’s Chernobyl moment that is unfolding in front of our eyes.

If you wanted to bet on the political structure least likely to survive the current “war”, then surely the European Union would be the bookies’ favorite? Today it would take a courageous politician indeed to argue that the European Union equals strength, and that further European integration is the road to prosperity and happiness.

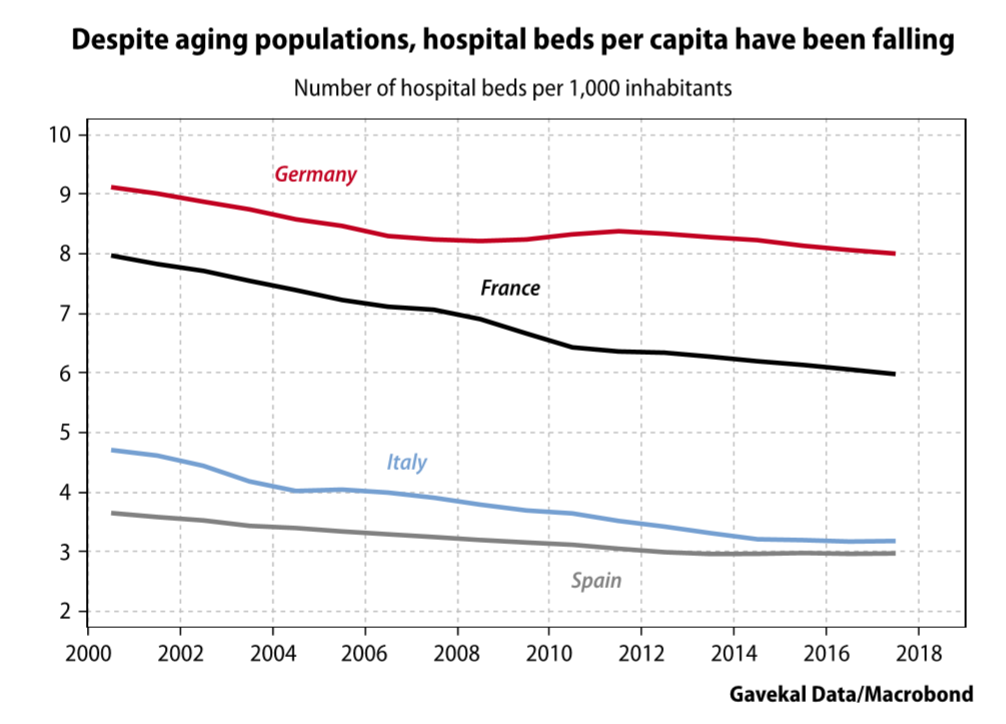

Instead, the question already being asked across Europe is whether the strict fiscal austerity imposed on Spain, Italy, Portugal and others in the wake of the 2012-13 euro crisis sowed the seeds of today’s crisis. People are complaining that to save the sacrosanct euro, national budgets got cut. And as cutting military spending was no longer an option, cutting national budgets meant slashing health care spending. Across Europe, hospitals shut down (especially in the countryside) and the number of hospital beds per capita fell despite aging populations. As a result, when the pandemic hit, medical systems that were already stretched to the limit quickly broke.

This brings me to last Thursday’s ill-tempered video conference of European government leaders. Having failed in epic style to display any kind of European unity, Europe’s leaders fell out over the notion that the current crisis should be midwife to the birth of pan-European government bonds. Such bonds are constitutionally forbidden in Germany (and a constitutional change would require a two-thirds vote in the Bundestag). Yet the Italian prime minister actively (and understandably) pushed for them. For now, European leaders have agreed to disagree, and to reconvene two weeks later. However, by then one of three things may happen.

At this point, which scenario looks the likeliest?

The United States

In any discussion about relative power shifts, the US usually starts with pocket aces. However, in today’s coronavirus crisis, things aren’t going very well for the US.

The combination of these factors will make for an even more emotionally charged November election than anyone expected (and before Covid-19 everyone was already expecting a more emotionally charged election than usual). The upshot is even more uncertainty for investors.

Three months ago, the broad consensus among investors was that in a world freighted with uncertainties, the US was by far the “cleanest dirty shirt”. The question today is whether this belief has now been shaken, and whether it will start to ebb as Covid-19 grips across the country and US domestic politics become even more aggressive and uncompromising.

China

Among the challenges of trying to see through the Covid-19 crisis in China is the reliability of the data provided by the authorities. China claims it identified its first case of Covid-19 on November 17, 2019 in a Wuhan hospital. That may well be true, although it is entirely possible that the virus was spreading across Hubei long before the first patient was admitted to hospital and identified as having something “atypical”. But what we know for sure is that China did very little about the virus until January 23, 2020, when Wuhan was put under lockdown. This means the virus had at least two months, and possibly longer, to spread unchecked around central China and beyond.

This is where it gets interesting. According to China’s official numbers, Covid-19 is responsible for 3,305 deaths out of the country’s 1.4bn inhabitants. In absolute terms, that is fewer than a third of the 11,591 deaths suffered in Italy, and Italy has a population of just 60mn.

So China, with a much bigger population, much greater population density, and a far inferior public health system, suffered just a fraction of the fatalities in Italy, Spain and now very likely France. How can we explain this dramatic divergence?

Reviewing these possible explanations of the divergence in death rates between Europe and Asia, it strikes me that the last three—superior policy implementation in Asian countries, better herd immunity across Asia, and inadequate health care systems in Western countries—all point to the same conclusion: investors should deploy more capital in Asia and less in Europe.

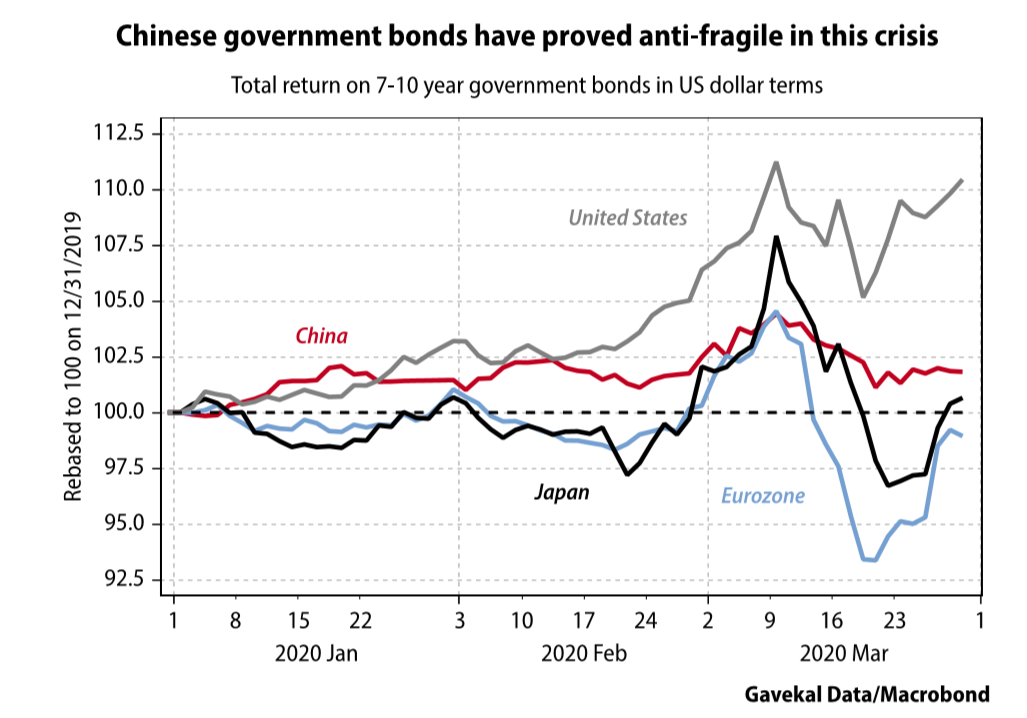

This brings me to a simple observation: this is the first time in my career that in the middle of a crisis Asian asset prices are not only outperforming (usually in downturns, Asian asset prices get beaten like a rented mule), but are outperforming with much lower volatility than Western assets.

Take renminbi debt as an example. In this crisis, renminbi bonds have proved the “anti-fragile” asset we always hoped they would be. Sure, they have underperformed US Treasuries. But renminbi bonds have outperformed US corporate bonds, eurozone government bonds and Japanese bonds. Better yet, they continue to offer a modicum of positive yield—which either promises future capital gains, or which will at least cushion the blow should yields elsewhere around the world start to rise again (see the chart below).

Perhaps more interestingly, while the correlation between US government bonds and US equity markets shifted dramatically in February and March, Chinese bonds continued to deliver uncorrelated returns.

Once the dust settles after a crisis in which cross-asset correlations became even stronger, the Chinese bond market’s near-unique ability to chart its own path will likely attract the attention of asset allocators everywhere. And this will be all the more true because unlike in 2008 or 2016, and unlike other governments in 2020, Beijing has not responded to the current crisis by plunging head first into massive fiscal expansion and monetary aggregate expansion.

In short, in the face of this crisis:

Given all this, should we be surprised that Asian assets are now outperforming Western assets? And is there any reason this outperformance won’t go on?

Conclusion

In 1944, the French Jewish playwright Tristan Bernard was arrested by the Gestapo at his home in Paris. As he was dragged away by the Nazis’ secret police, he enjoined his distraught wife: “Do not cry. We were living in fear. But from now on we will live in hope.”

Today, there is a lot to be fearful about.

The list could go on. But if readers are not feeling as distressed as Mme.* Bernard, it is unlikely they are exactly dancing for joy. Still, amid this disaster, we should remember these points:

*Mme. is an abbreviation for "Madame" or "Mrs."

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.