Introduction

The modern venture capital (VC) industry emerged when two venture capital firms were founded in the wake of World War II: American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC) and J.H. Whitney & Company. ARDC was founded by Georges Doriot, the "father of venture capitalism", to encourage private sector investments in businesses operated by soldiers returning from war. J.H. Whitney & Company was founded by John Hay Whitney and his partner Benno Schmidt, who famously invested in Florida Foods Corporation (which later became known as Minute Maid and was sold to The Coca-Cola Company in 1960).

Before World War II, investing in young, growth-oriented companies – originally known as "development capital" before venture capital was a coined term – was mostly reserved for affluent individuals and their families. However, in an effort to spur technological advances and compete against the Soviet Union, the Federal Reserve Board concluded that a major gap existed in capital markets for the long-term funding of growth-oriented businesses. This led to the passage of the Small Business Investment Act of 1958, which allowed the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) to license private "Small Business Investment Companies" (SBICs) to help with the financing of fledgling, entrepreneurial businesses in the United States.

Since the birth of this asset class, there have been four major epochs marked by three boom and bust cycles. Perhaps the most infamous is the second boom-bust cycle which culminated in the massive Dot-com bubble in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Up until that time, private equity and venture capital were almost exclusively located in the United States. However, with the liberalization of regulations for institutional investors in Europe, a mature venture capital market began to emerge “across the pond” in the mid-1990s.

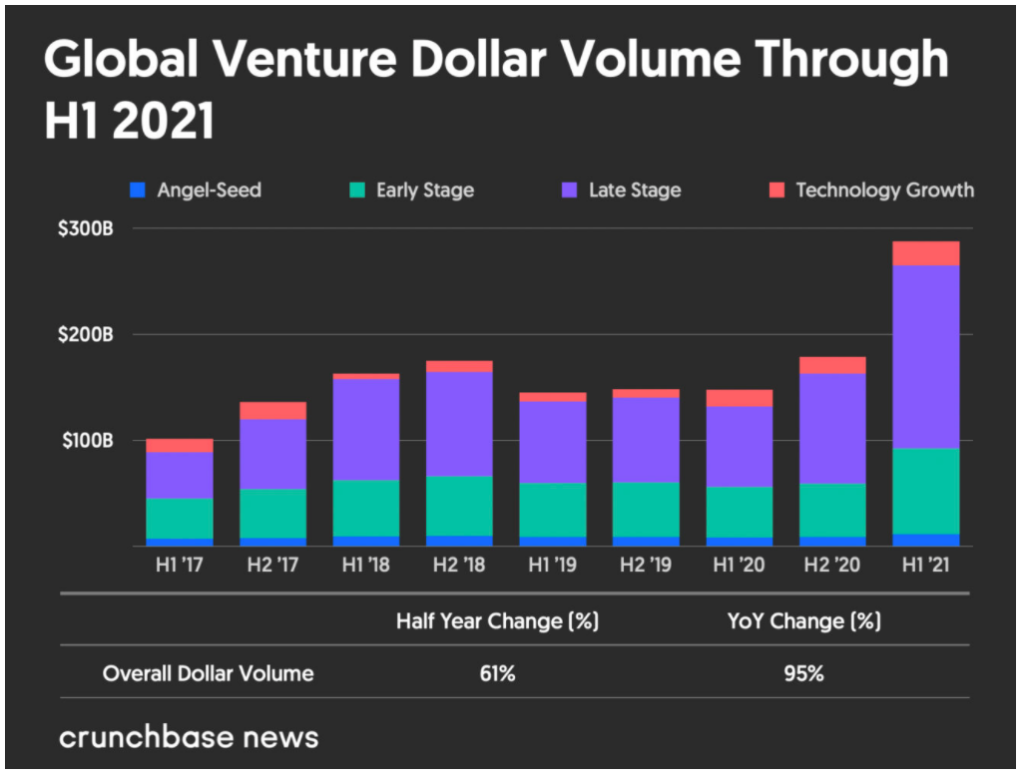

Recently, the venture capital industry has been top-of-mind for global investors. With the support of strategic-growth capital, many companies that were birthed in the wake of The Great Recession ascended from down-on-their-luck garage-concepts to multi-billion-dollar businesses in a matter of years. As a result, this unprecedented wealth creation attracted new capital seeking high-risk, high-reward alternatives to public market investments. Proving how rampant the rise of this alternative asset class has been lately, global venture capital funding in the first half of 2021 shattered records with more than $288 billion invested worldwide. That’s up by almost $110 billion compared to the previous record that was set in the second half of 2020.

Despite its rise in popularity as an alternative asset class, high-net worth individuals still have disproportionate access to venture investments. Much of that is by design, as accredited investor requirements in the United States limit venture exposure to “sophisticated investors” or those with a special status under financial regulation laws. However, this means that the average investor has limited opportunities to invest in a diverse array of securities, specifically privately held, small-to-medium sized businesses. As we wrote about in 2019, the case of the elongated IPO further compounds this issue by bringing companies to market later in their funding cycle, thus introducing them to public markets – and average investors – at pricier and pricier valuations.

A Purely European Model

Recently, European Venture Capital Funds have been in the news – but not only because of the promising startups they’ve funded. Instead, European VCs have made headlines by announcing public listings of their own securities. At first blush, this may seem odd as these firms have traditionally invested in companies that they hope to see go public. However, at second pass, the concept is quite intriguing for a couple of reasons:

Despite the rising popularity of these public listings in Europe, US venture funds are nowhere to be found in the emerging landscape of publicly-listed VCs. Interestingly, American Research & Development, the very first modern VC firm mentioned earlier, was actually publicly owned. But, as a listed closed-end investment company, regulators prohibited it from rewarding its employees with equity stakes or options in either the firm itself or their portfolio companies. As a result, the lack of incentives for senior dealmakers led to subpar performance.

The brief history lesson from the world’s first VC may be one reason why US firms have chosen to shun public markets. Another reason is the desire to remain highly confidential in their business dealings. Afterall, the prestige of being listed – and the increased accountability that comes with higher public-market standards – requires regulatory disclosures that can draw unwanted attention to the innerworkings of the industry.

A New Playbook for VC?

One of the questions in the VC space is whether the trend in Europe will gain momentum and eventually make its way back across the pond. The advantages of accessing deeper pools of capital – whether it be from institutional investors who prefer to invest in liquid securities or retail investors – make it possible for VCs to experiment with long-term oriented models where ‘permanent capital’ allows them to be even more patient with their investment selections.

However, with the recent burst of capital into the space, new entrants, and incumbents that are raising bigger and bigger funds to stay competitive, US-based funds are less likely to rewrite the VC playbook anytime soon. On the other hand, European VCs lack the same deep-pocketed institutional investors, pension funds, and endowments that back the elite US funds on Sand Hill Road (in the heart of Silicon Valley). This makes turning to public markets much more attractive, despite some of the obvious disadvantages mentioned above.

In the coming years, it will be interesting to see if some of the middle-tier, US-based VCs lean into the European model to remain competitive and raise their profile in an attempt to access better deals. When investment banks started going public in the 1970s, it was the niche players that jumped into public markets first. The industry’s leading firm, Goldman Sachs, waited until May 1999 to list its shares on the New York Stock Exchange.

So, while the average investor is unlikely to gain access to deal-flow from Sequoia Capital or Andreessen-Horowitz anytime soon, the new European model cracks the door open to the possibility that retail investors might be able to access the United States VC asset class someday. The timing of the industry’s next boom-bust cycle might have a lot to do with that. For now, boom away…

Michael Johnston

Tech Contributor

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.