“We’re paddling against the current in trying to sustain public faith in the Fed.”

–Federal Reserve Chairman JEROME (JAY) POWELL

“The FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee, the Fed’s key rate-setting entity) is in panic mode now, facing the Frankenstein monster balance sheet it has created. The FOMC has come to the realization that it cannot unwind it.”

–Jones Trading’s chief strategist MIKE O’ROURKE

“The Fed today is as much a prisoner of the market as the market today is a prisoner of the Fed.”

–Epsilon Theory’s BEN HUNT

At the beginning of 2018, we initiated a new EVA series titled “Bubble 3.0” with excerpts from David Hay’s upcoming book titled “Bubble 3.0: How Central Banks Created the Next Financial Crisis”.

If you are just joining us in the middle of this ongoing series, which will eventually culminate in a full-length publication, please take a few moments to review the prior installments in the series:

In this month’s edition, David looks at how a recent policy pivot from the Fed could create a longer-term crisis with no way out for the US economy or stock market.

BUBBLE 3.0, CHAPTER 10: NO WAY OUT

“Big hat, no cattle”. “All sizzle, no steak”. “Talks a good game”. Those and other popular sound-bites are meant to refer to someone who is, to use another colloquialism, “all bark and no bite”. When it comes to most of the world’s central banks, all of those quips apply.

If you think I’m being excessively judgmental, consider recent developments: The European Central Bank (ECB) has been adamant about its desire to both begin raising interest rates and shrinking its bloated-like-a-Sumo-wrestler-on-steroids balance sheet.

Adamant, that is, until recently. Thanks to weakening inflation and continuing anemic growth on the Continent, rate hikes are off the table. Soon-to-be-outgoing ECB emperor chief Mario Draghi is already making noises about restarting its quantitative easing (QE) program rather than reversing it as its American counterpart, the Fed, has done. This is despite the fact that the ECB’s balance sheet—or stash of European bonds bought with pseudo-euros—is an outrageous 40% of GDP versus “only” about 20% in the case of the Fed (GDP represents a country’s total economic output).

It’s true that Europe’s chronically flaccid economic pulse has faded one more time (European economic “liveliness” almost makes a corpse look animated). As a result, the number of negative-yielding bonds (the ultimate Alice In Wonderland financial condition where borrowers charge lenders to use the latter’s money) is once again swelling. The total value of these legalized investor extortion instruments is now $11 trillion, most of them from European issuers. This is up from the trough of $6 trillion last year when it seemed as though the ECB was serious about at least a feeble attempt at returning to normal monetary conditions (like where lenders get paid to extend credit).

Accordingly, it looks like the rumors of the demise of negative yields have been greatly exaggerated. Per the below, from the Wall Street Journal, almost a quarter of all global bonds outstanding produce, so to speak, negative interest rates.

In Japan, the land of the sinking yen and ever-rising debt, conditions have also flagged lately despite decades of zero interest rates and stupendous deficit spending. One of its most influential business conditions surveys recently noted: “Domestic economic weakness compounded with slowing global growth coincided with the lowest level of business confidence for over six years.”

As the no-nonsense financial commentator Danielle DiMartino Booth, former adviser to ex-Dallas Fed president Dick Fisher, recently wrote: “Not to beat a very dead horse but negative interest rates in Japan and Europe were supposed to have generated virtuous outcomes.” (Emphasis hers.) In other words, these radical policies, that were designed to stave off the ravages of the Great Recession and stimulate healthy economic growth, continue to fail to bring home the mail.

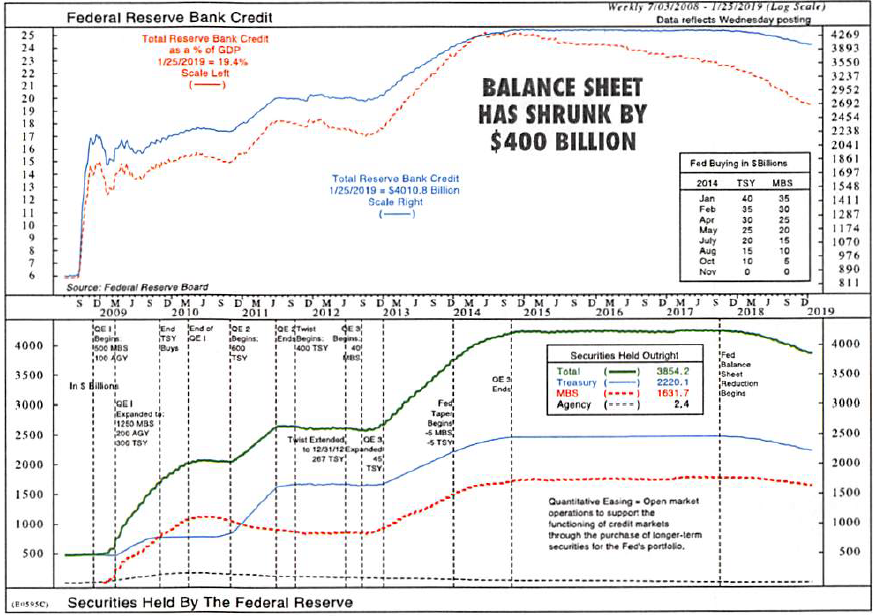

Then there’s America and its relatively new Fed chairman, Jerome Powell (Jerome sounds much more forceful than Jay, the handle he seems to prefer, doesn’t it?). Jerome came in with both guns blazing, raising rates and shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet, what we and others (like Danielle) have called a double-tightening. (As a reminder, increasing the Fed’s balance sheet was popularly known as quantitative easing or QE, which was where it essentially created $3.8 trillion of fake money to buy government debt. Other central banks, such as the ECB, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England, and the Swiss National Bank also engaged in this monumental monetary fabrication.)

As recently as last fall, Mr. Powell “talked a good game” of ignoring market volatility (meaning sell-offs). He even hiked rates in mid-December despite a reeling stock market. He additionally seemed intent on continuing the double-tightening, also announcing in December that the balance sheet shrinkage—or quantitative tightening (QT)—was on “autopilot”. Based on the press conference he gave at the end of January, apparently that autopilot has already been switched off.

Many pundits have reacted to this about-face angrily and are accusing Jay (not Jerome) of caving into political pressure from the meddler- (and Tweeter-)-in-chief. Others have screamed that he has done exactly what he said he wouldn’t do by trying to sooth the stock market with dovish utterances once it was down about 20% from its September peak.

Conversely, the preternaturally bullish crowd on CNBC, especially Jim Cramer, have been delighted with Powell’s almost overnight conversion from hawk to dove. (On that topic, I was interested, but not surprised, to read that when the long-bearish John Hussman appeared on CNBC a few weeks ago, he was told to put a positive spin on his views. Talk about fake news! But to his credit, John didn’t dilute his message.)

Certainly, the stock market has loved the Jerome to Jay metamorphosis. From a selfish standpoint, Evergreen is in the pleased camp since it has been the bombed-out strata of what we’ve been calling the two-tier US stock market that has been in the vanguard of this powerful rally since the late December lows. In fact, energy in general and mid-stream energy assets (pipelines, et al) in particular, have been at the head of the charge, as we had hoped and anticipated, per our early January special message.

But from a non-selfish vantage, I have serious misgivings about how even the most timid attempts at so-called monetary policy normalization (read: getting interest back up to a point where savers care about saving) caused things to fall apart. Also from a self-centered view, that’s a vindication. Whenever I was asked (and often even when I wasn’t) how long the Fed would tighten, my simple answer was: “until something breaks”. It’s fair to say that a lot of things broke—make that shattered--in the financial markets in last year’s fourth quarter and we now believe the Fed is done with actual rate increases. (The continuing balance sheet shrinkage, effectively representing further rate hikes, is a different story.)

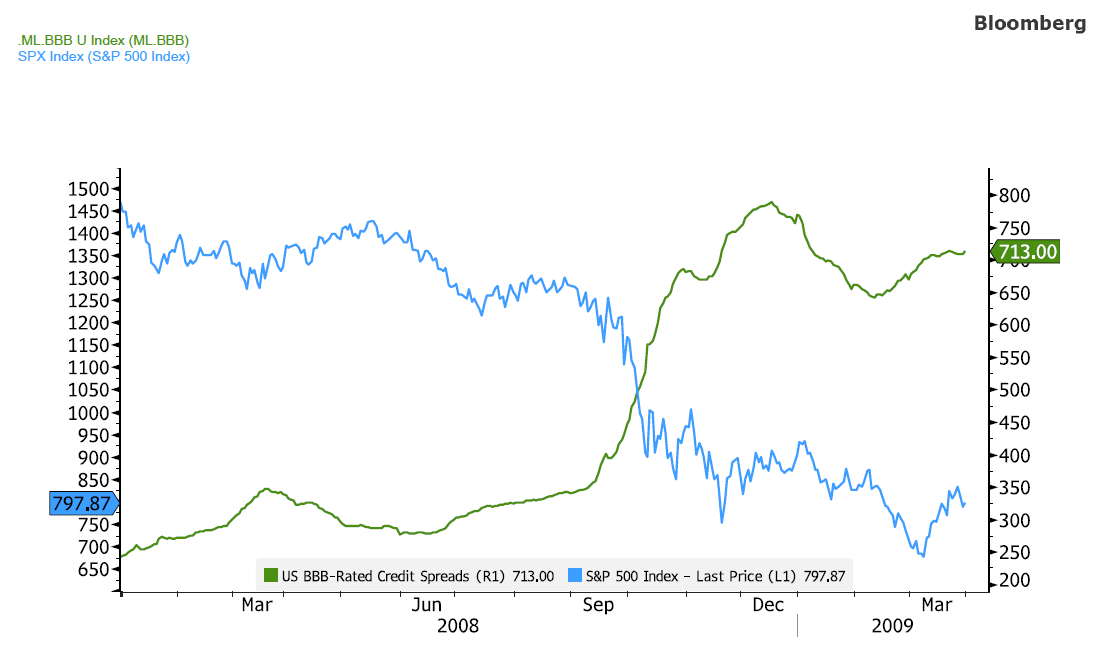

As usual, stocks hogged all the press during last quarter’s crashette but I’d argue another development alarmed the Fed just as much…if not more. EVAs ad nauseum (no doubt nauseating many of our readers in the process) have conveyed the vital role of credit spreads. Also, ad nauseum, we’ve explained that these represent the gap between the government’s borrowing costs and those of Corporate America. We’ve also repeatedly noted that when those contract it’s very good news and when they widen, especially “bigly”, it’s head-for-the-hills time.

The above chart shows what’s been going on with spreads over the last five years. You can easily see that when they’ve been narrowing, or are stable, the stock market does just fine. However, when they zoom higher, red ink tends to flow down the canyons of Wall Street.

What was a bit different this time is that stocks seemed to lead credit spreads rather than the other way around, as is more common. To illustrate the typical sequence, witness what happened to spreads and stocks in 2007 to early 2009, as well as in 2011 and 2012.

But it is probably fair to say that the spike by spreads late last year elevated what was a mere correction into a near bear market for the S&P. Moreover, there was no “near” about it for most overseas stock markets, US small- and mid-cap stocks, and, frankly, most US issues save a few monster-cap names like Amazon, Netflix, Google, and Microsoft (i.e. the majority of the famous FANGM). Said differently, what was an already very painful dive of almost 20% by the S&P was far worse for a wide range of asset classes and individual stocks.

Thus, it’s likely that this darker backdrop was a key reason for the Jerome to Jay, monetary muscleman to monetary milquetoast, changeover – kind of like Superman reverse-morphing back to Clark Kent. As we noted at the end of December, it was becoming an out-and-out panic. Just as we saw at almost the exact same time of the year in 2008, those type of events can get out of hand very quickly. Once they’ve done so, it can be extremely challenging to convince terrified investors to get a grip.

If it sounds like I’m asking for some slack to be cut for old Jay (who’s actually just about my age, so, naturally, I don’t think he’s THAT old), I guess I am, emphasis on “guess”. The fact of the matter is I simply feel resigned to the ugly reality of current conditions. As I noted in the “What Price Prosperity” chapter, the reigning King of Bonds, Jeff Gundlach, summed it up best, in my view, when he said: “The Fed is damned if they do and damned if they don’t.” Ergo, they’re doomed if they keep tightening and they’re doomed if they stop.

Maybe you think doomed is too harsh a word, and perhaps it is. But I think what’s becoming increasingly clear is that the leading global economies are doomed destined to occupy a twilight zone of chronically deficient growth, rapidly rising debt levels, and a constant absence of interest rates. Frankly, I think the Jim Cramer’s of the world salivate over this scenario because they feel it means the US bull market isn’t dead after all. With the Fed on hold, it’s a greenlight for investors to go back into full risk-on mode, as they have most enthusiastically done this year. Or at least that’s how the current market narrative is shaping up.

To repeat, my personal portfolio and those of Evergreen clients are loving this revival of animal spirits. Even our most conservative strategy is off to a very fast start thus far in 2019. But down deep, and not really that deep, it seems to me the market is making a monstrous mistake. It’s not asking another one of those nagging questions—like what price (pseudo) prosperity?—such as, “What’s the ultimate end-game?”

With profuse apologies to all those who put their lives on the line in Iraq and Afghanistan, it feels to me like the financial equivalent of those quagmires. The US and its allies put enormous military force to work in both countries and, in fairly short order, were able to “win” both wars. But it seemed to me at the time, and it still does, that we never thought about an exit strategy. (It was illuminating in this regard to watch the PBS American Experience tribute to the life of George H. W. Bush. In it, several of his top advisers from the first Gulf War were interviewed and they recounted how much heat they took after it was over for not marching into Baghdad and deposing Saddam Hussein. Each of them pointed out they don’t hear those criticisms any longer after the world has had a chance to witness the near-impossibility of fully exiting either Iraq or Afghanistan.)

Basically, the US high command employed a massive military intervention. It had a brilliant plan to win the wars but, apparently, almost no plan to win the peace. Similarly, the planet’s central banks never seemed to have a sound strategy for withdrawing from their decade-long, multi-trillion experiment, one that has never been tried before—perhaps for good reason.

As noted earlier in this series, and we will see again at the end of this chapter, our forecast has long been that it will shock most people how little tolerance even the US has for higher interest rates. The market tumult of last quarter was one vivid illustration. But there’s more at work here and I think this is what the market is missing right now in its “O, Be Joyful” reaction to Jay Powell’s flip-flop. To quote Bill Clinton’s former top political strategist, James Carville: “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Lost in all the anxiety, followed by euphoria, over the Fed’s stance and the market’s response to same – not to mention the confusion of the government shutdown – is what is happening to economies both in the US and the rest of the world. Unquestionably, Germany is the lead sled-dog for the European economy and the industrial production numbers it’s been reporting in recent months have been shockingly weak, now down 4% year-over-year. Even German retail sales have recently done a cliff-dive. This is quite a letdown given the supposed health of the Deutschland consumer. Much less surprising is that Italy is sliding back into recession for what seems like the tenth time in the last ten years.

Spinning the globe roughly 180 degrees, China is experiencing what passes for a recession in that country. So far, it’s a growth version--if official numbers can be believed (and that’s a big leap of faith); if not, then you can remove the “growth” part of the description. Even so, China has been reporting the weakest economic data in 30 years. Naturally, stagnation in China ripples throughout the entire Asian region.

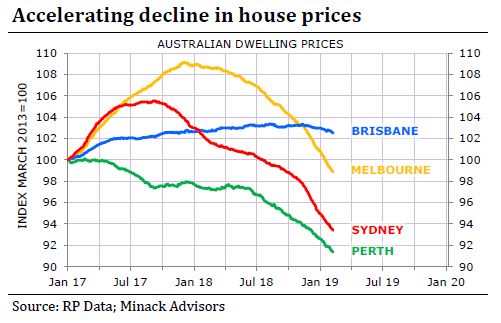

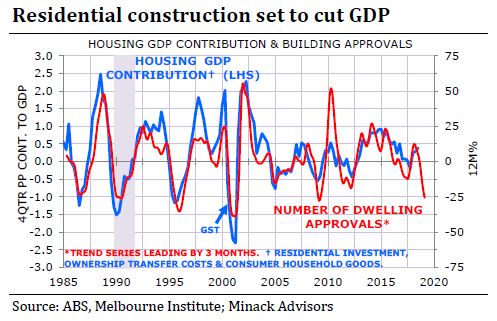

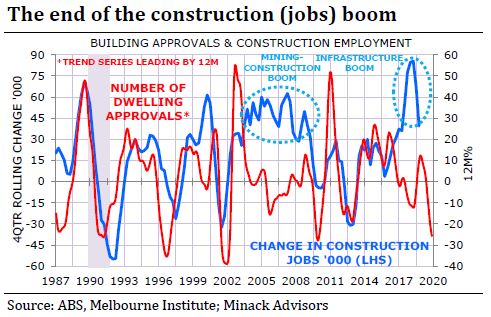

Even the “Lucky Country”, Australia, which has been fortunate enough not to have endured a recession in twenty-five years, looks like its luck is running out. Over that time, it has experienced one of the most outrageous housing bubbles ever recorded. Thus, its economy is at grave risk should housing prices decline precipitously. As Sydney-based Gerard Minack pointed out in his February 8th Down Under Daily, “The risk of an Australian recession is rising.” To back up his view, note a few of the charts he ran in that issue.

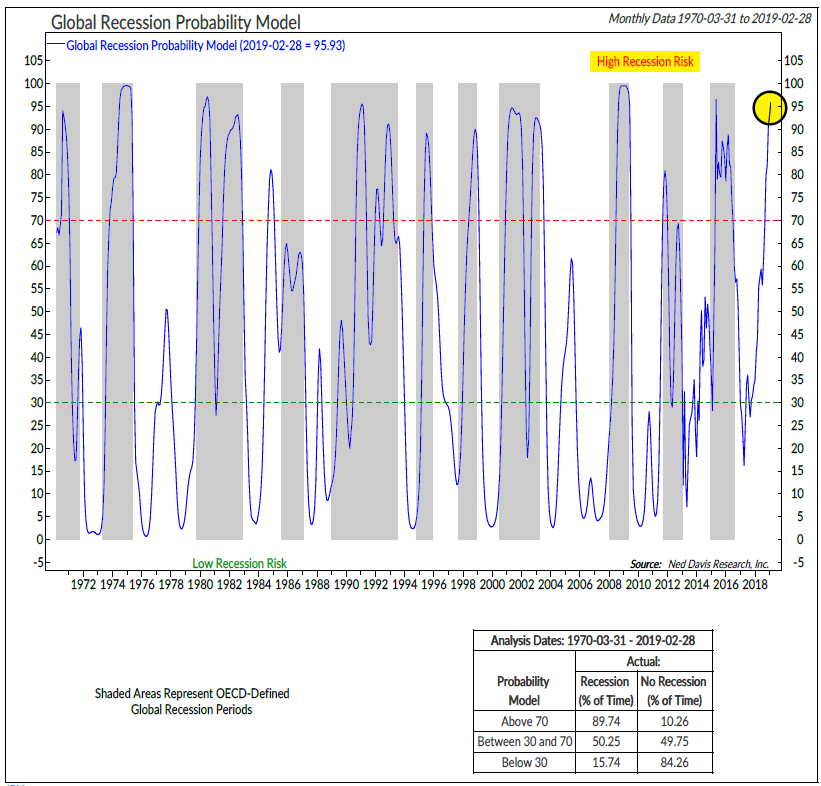

Consequently, most of the planet’s leading economies look to be heading into contraction mode. Prior Bubble 3.0 EVAs have shown the Ned Davis Global Recession Watch chart and here’s an updated version.

Of course, what US investors care most about is our domestic economy. In that regard, it continues to amaze me how much focus there is on the labor market. In case you missed it, the latest jobs report released, on February 1st was a scorcher…at least on the surface. Some 300,000 jobs were created, reinforcing the view that the US has been able to decouple from the rest of the world’s slowdown/recession.

But, as often noted in these pages, the unemployment report is one of the most retro economic measures known to either woman or man. It only tells us about the past and precious little about the future. The closest thing the economic profession has to a media star these days is Gluskin Sheff’s David Rosenberg. David has done a 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea dive on the latest jobs report and he’s come up with a radically different take on the tale it tells.

First, he notes that the Household Survey (vs the official Payroll Survey) has historically been much better at identifying turning points in the jobs cycle. At the same time that the main report indicated strength, David noted that the Household Survey showed 250,000 jobs lost. He also points out there’s something very odd about recent studies of the prime working-age category of 25 to 54 years old. For the first time since April 2009 (i.e., the heart of the Great Recession), it has contracted for three months in a row. Meanwhile, the broader measure of jobs market, known as U-6, has risen from an unemployment rate of 7.4% to 8.1%, nearly as much as it did leading up to the total economic face-plant back in 2008.

The aforementioned Danielle DiMartino Booth is on the same scent on almost a daily basis through her Quill Intelligence service. (By the way, her Daily Feather is a steal at just $25 per month; you can sign up via this link.)

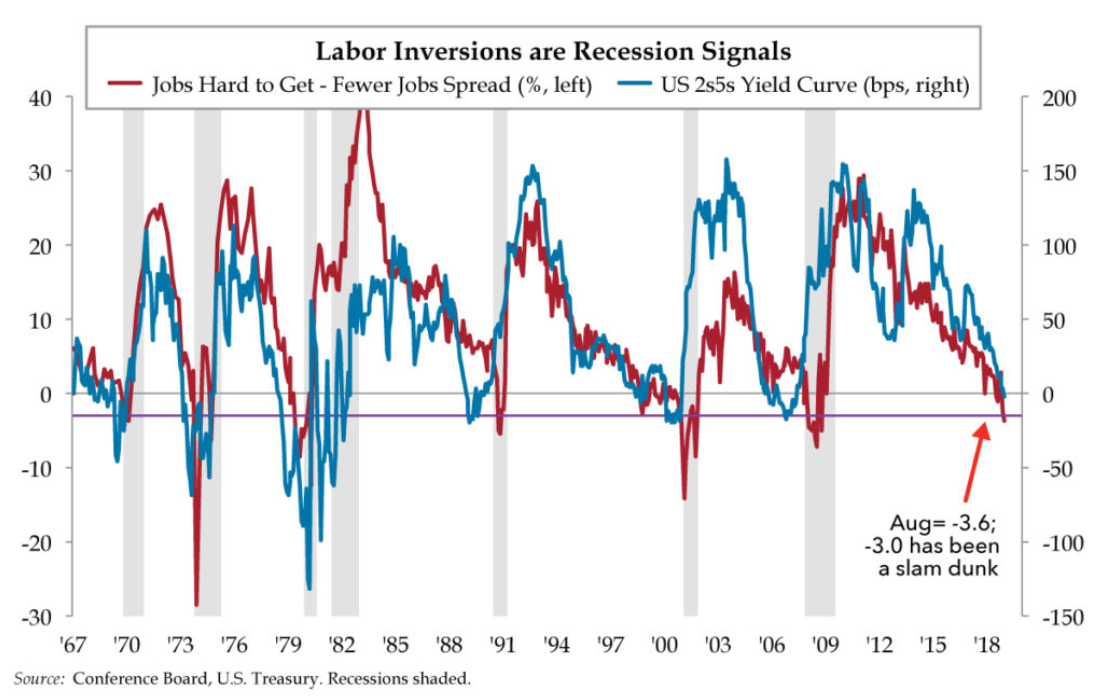

As far as I’m aware, Danielle is the only economic maven who tracks inversions in both the yield curve and the labor market. Most of us are familiar with the former (a yield curve inversion occurs when short-rates are higher than long rates, a condition that has already occurred in parts of the US treasury debt market) but the latter is more obscure. Per the following chart, she tracks “Jobs Hard to Get” minus “Fewer Jobs”.

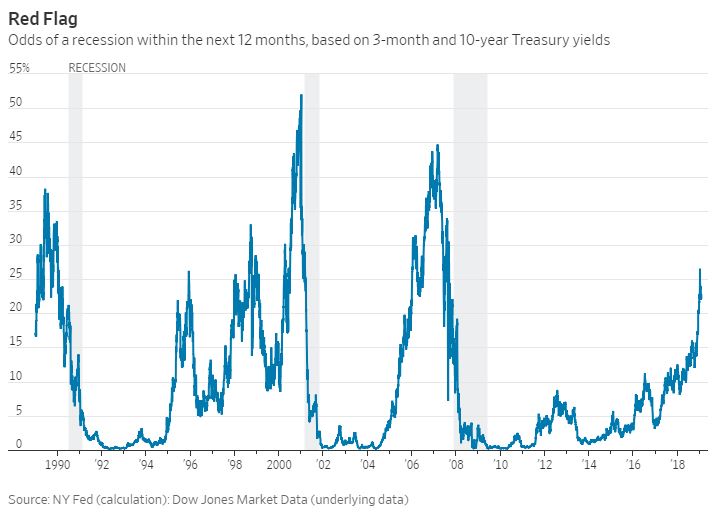

The spread between those has provided a remarkably accurate warning in the past about a turn for the worse in both the labor market and the overall economy, as you can see above. The idea behind this is that when a bottom happens in “jobs hard to get” (i.e., they are easy to get), as happened last August, and then “fewer jobs” becomes a trend, a reversal from expansion to contraction is likely. In fact, over the last 50 years, recessions have been around the corner in six of the past seven times this has happened. As she points out, it’s also no coincidence that these two inversions happen in synch. An inverted yield curve is one of the most reliable advance warnings of an impending recession.

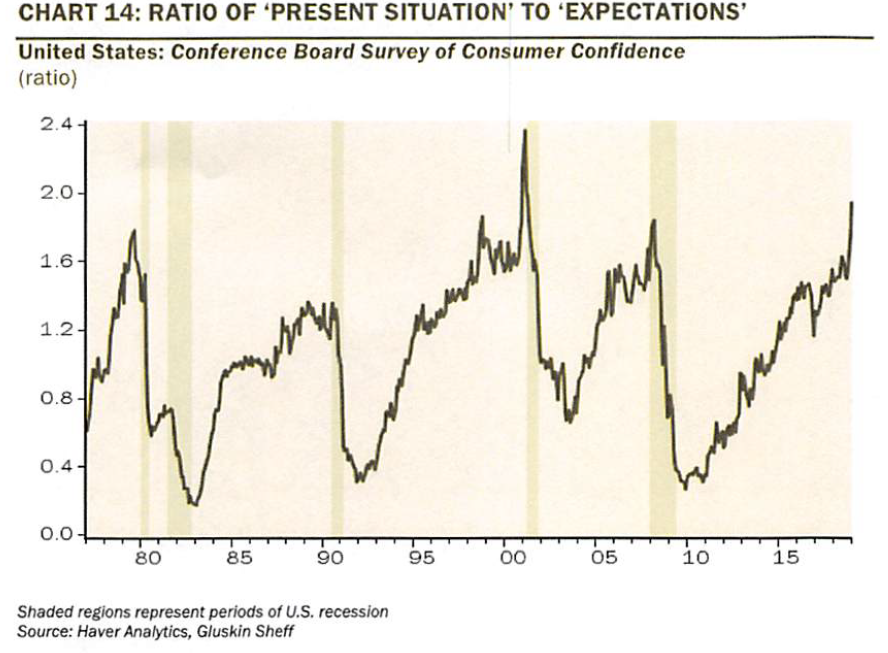

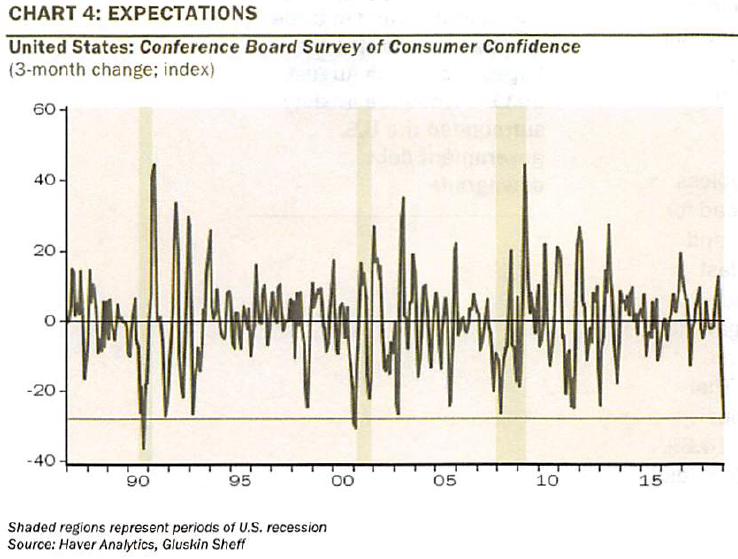

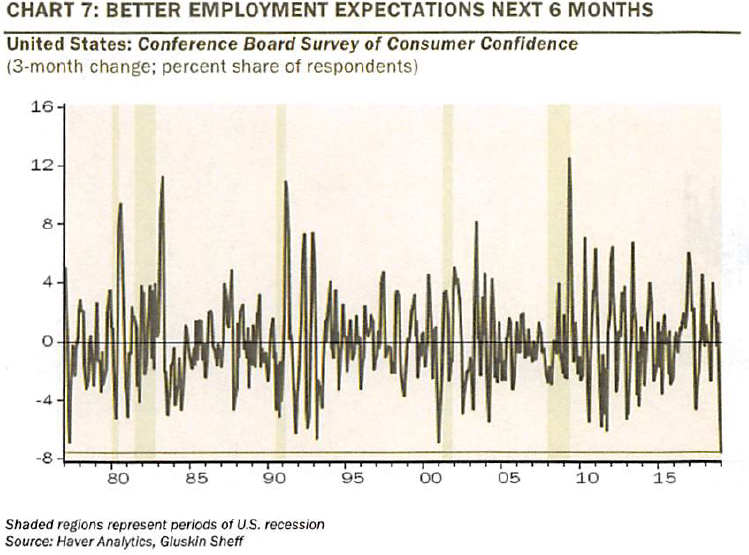

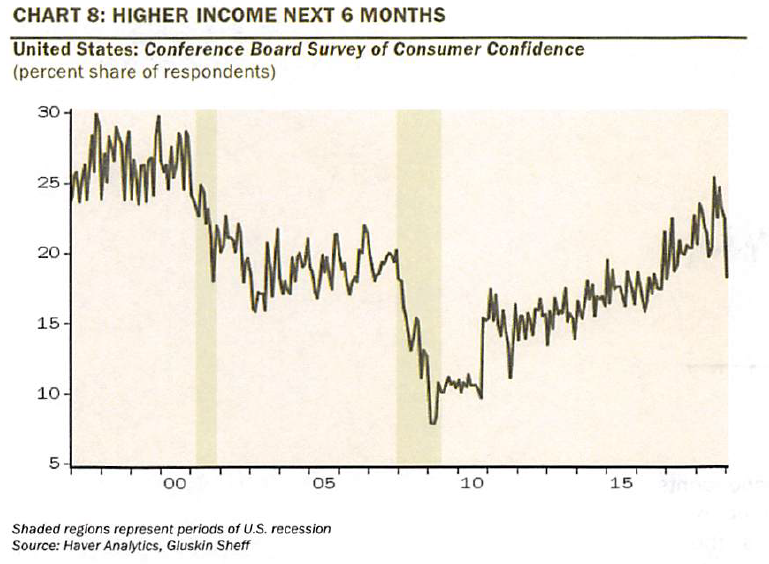

Still skeptical? Well, David Rosenberg, Danielle DiMartino Booth and the new King of Bonds, Jeff Gundlach (the erstwhile Bond King, Bill Gross, just hung up his Bloomberg) all further state that another highly reliable heads-up of an impending downturn is the difference between consumer views of current vs future conditions. The logic behind the theory is that when households feel fine about their present status but are becoming increasingly concerned about the future, an economic pivot point is also nigh at hand.

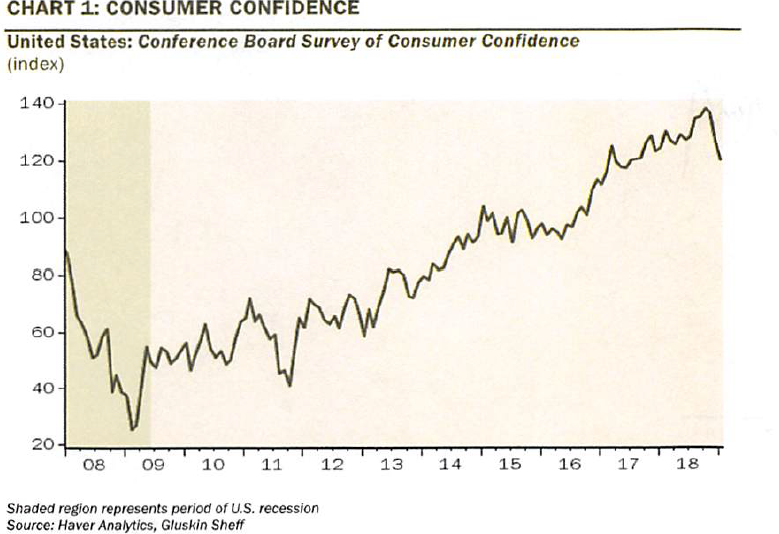

The good news with this indicator is that it hasn’t for sure peaked out. The bad news is that it is looking perilously close to where it was at the conclusion of past expansions. Based on the below charts measuring consumer confidence, it does appear a turn for the worse is looming.

As Danielle has summed it up recently: “Make no bones about it. ‘Recessionary’ best captures the last three months’ decline in the Conference Board’s Consumer Expectations index. The 27.8-point drop through January was the fourth largest on record. The other four declines comprise the top five which presaged past recessions.” (Emphasis hers)

Along similar lines, restaurant sales tend to be a reliable indicator of future consumer discretionary spending. They’ve now fallen in four of the last five months and are dropping at the steepest rate in 25 years. Maybe that’s why articles like this are popping up in the Wall Street Journal.

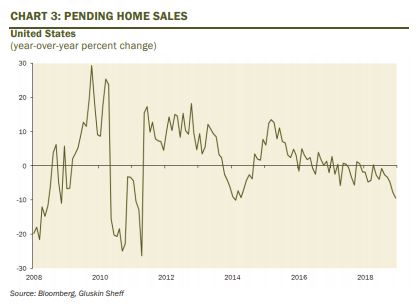

Housing also tends to lead the economy and the trend in home sales is another ominous development. In the Seattle area, home prices are sliding at rate nearly as fast as in 2009.

Besides the fact that almost nary a Wall Street strategist is talking about these realities—yet—all of the above economic factoids are unlikely to have escaped the Fed. This is notwithstanding the recent comment by Jay Powell that “the US economy is now in a good place.” Remember, the Fed has never predicted a single recession in its history. Maybe this is because it feels it must constantly put on a brave face to avoid creating a self-fulfilling situation. But behind closed doors, around its massive gleaming conference table, it’s probable the Fed-heads are looking at the same data I’ve shown.

Therefore, if stock investors are celebrating the Jerome-the-Hawk to Jay-the-Dove conversion, while ignoring the deteriorating economic backdrop, they are likely falling into a trap much as they did in late 2007 and early 2008. Back then, the stock market staged several robust rallies, as the Fed first paused and then eased, before the realization set in that a recession was bearing down on the world.

Putting that aside, let’s consider the plight of the planet’s largest investor cohort, the Baby Boomer generation. Beyond their exposure to another market meltdown like last quarter’s, what about their need for yield? If the world’s central bankers can’t exit from these emergency programs that have been in place for a decade now, when can retired, or soon-to-be retiring, investors expect to ever be able to earn an interest rate above inflation on their income portfolios?

As relayed by Mike O’Rourke in his January 30th edition of The Closing Print, here’s what then Fed chairman Ben Bernanke had to say to Congress back in April of 2009 about QE (quantitative easing, the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet with pseudo money):

Question: “Do you think this extended balance sheet should be maintained permanently or do you think it should be a temporary fixture?”

Answer (Chairman Bernanke): “No. It’s a strictly temporary measure which is being used, given that the interest rates are down to zero…But clearly this is a temporary measure which is intended to provide support for the economy in this extraordinary period of crisis and when the economy is back on the road to recovery, we will no longer need to have those measures.”

As economist extraordinaire, Milton Friedman once wryly noted, “nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program”. He must be smiling down from his cluttered desk in the sky saying: “Told you so”.

What is truly extraordinary is that nearly 10 years and one of the longest expansions in history later, the Fed’s balance sheet is much larger today than it was in April of 2009. If you include all the other central banks’ balance sheets around the world, the effective amount of QE now dwarfs what it was during the worst of the Great Recession.

But the really pathetic part is that current events indicate there is no exit for the monetary mandarins. While the Fed is continuing to reverse its QE—what’s known as QT or quantitative tightening—it has also effectively admitted that its balance sheet will remain much larger than it envisioned as recently as December. Instead of pursing QT for three years, it now sounds like it will finish later this year—or sooner if the stock market craters yet again.

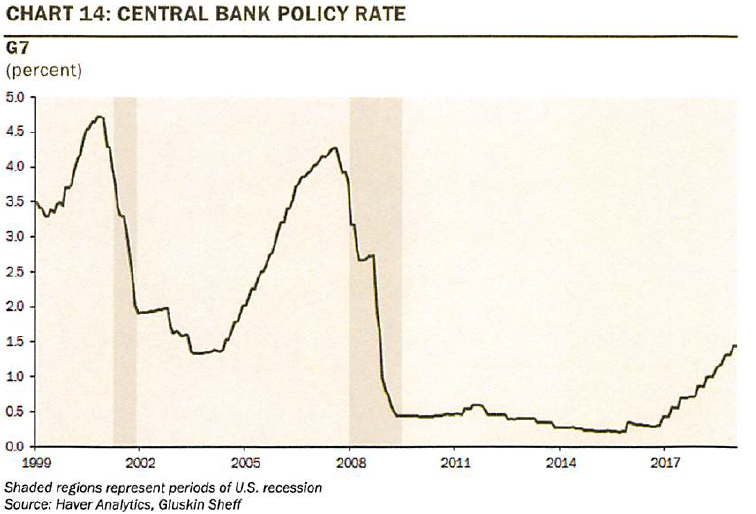

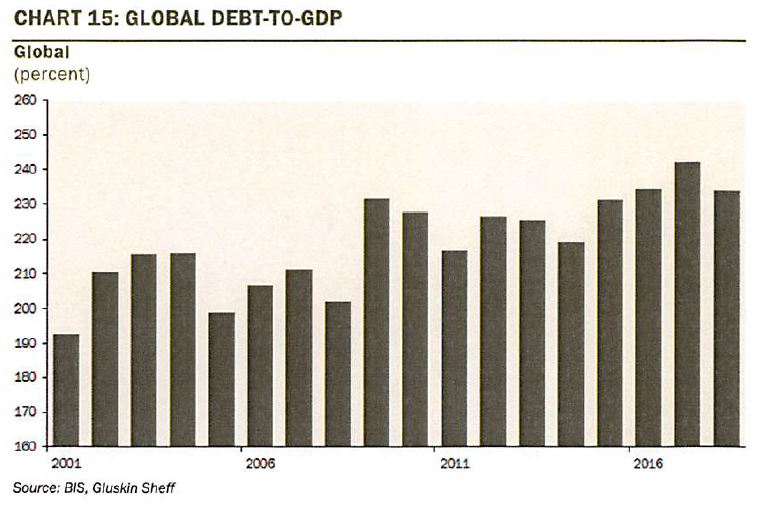

Returning to the less esoteric central bank tool of interest rates, the fact that so much market turmoil—notwithstanding this year’s relief rally--and what looks to be the onset of another global recession, money market yields are still at what used to be recession levels. In my mind, this is totally a function of how over-leveraged the planet has become, making it highly vulnerable to even mild rate-hiking campaigns.

A couple of the important implications from all of the above are as follows:

Further, hopes of ever being able to earn something like 5% on reliable income investments are nil outside of equity-like securities such as mid-stream energy securities (pipeline-type MLPs) or on corporate bonds when credit spreads soar (as started to happen last year and may occur again soon). But there are risks with these investments as we saw vividly in the fourth quarter when both MLPs and corporate bonds took it on the chin, particularly the former. But if Boomers are going to earn a decent cash flow yield on their nest eggs, they are going to need to take some calculated risks. One of the best times to do so is after the Fed has cut rates repeatedly and the economy is clearly in recession. Obviously, we’ve got a long way to go before those criteria are met. In other words, the next great buying opportunity in corporate yield securities likely is a later-in-2019 event. (Past EVAs have generally given decently timely recommendations of when to capitalize on these episodes.)

Unfortunately, with the central banks looking increasingly caught in a trap of their own making, it’s likely we are facing a Japan-like scenario in much of the world. In case that doesn’t resonate with you, this means a multi-decade period of economic stagnation and interest rates gone missing. But it also doesn’t imply the end of the world. You may have noticed Japan is still a prosperous country. Yet, the other reality is that growth has become very hard to come by in what was once a nation that looked to be dominating every industry (and buying up what seemed like the most iconic US trophy properties).

This debt-drenched/low growth/puny interest rate world is certainly not what I want to see but to hope otherwise is to believe folks like Jay Powell have the chutzpah-- and wherewithal--to reset interest rates well above the inflation rate. Frankly, even if they wanted to, I don’t think they can…at least not without triggering an excruciating bear market in stocks, real estate and junk bonds/highly leveraged loans (the latter two continue to be my top vote-getter for the next panic flash point). That, in turn, would almost certainly catalyze a wicked recession. Therefore, cue again, the Gundlach “damned if they do, damned if they don’t” assessment.

To close this chapter of Bubble 3.0, I’d like to quote Michael Lewitt, the unflinchingly candid author of The Credit Strategist. Mike sent this to me in an email at the end of last month and gave me his permission to share it with you: “The Fed is a total joke. It is clear they view their job as protecting the stock market. Powell is just another Yellen who was another Bernanke who was another Greenspan. They will destroy the world.”

The world’s a resilient place, at least for those parts of it that protect free markets, including allowing investors to earn an acceptable return on their capital. But, these days, what’s acceptable in the minds of the central bankers seems to be shrinking with nearly every economic release.

Fascinatingly, though, the main topic for the next chapter of Bubble 3.0 may provide a way out, after all. It’s already beginning to garner significant media coverage with much more likely to follow. To many, it is the only viable exit strategy from this quagmire our dear central banks have created with their fealty to the faulty logic that punishing savers for years and years is a good thing. If you can’t wait a month or so to learn what I’m rambling about…well…sorry. There’s an old show biz saying that you should always leave your audience yearning for more. Just this once, I’m going to follow that advice.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

Changes highlighted in bold.

LIKE *

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

* Credit spreads are the difference between non-government bond interest rates and treasury yields.

** Due to recent weakness, certain BB issues look attractive.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.