“Boards of directors who are allowing buybacks to occur without being transparent about allowing CEOs to sell into them raise real questions about the leadership of that board.”

– SEC Commissioner Rob Jackson

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

At the end of 2017, we initiated a new EVA series titled “Bubble 3.0” with excerpts from David Hay’s upcoming book titled “Bubble 3.0: How Central Banks Created the Next Financial Crisis”.

If you are just joining us in the middle of this ongoing series, which will eventually culminate in a full-length publication, please read the prior installments in the series here:

In this month’s Bubble 3.0 missive, David discusses how unprecedented share repurchases have fueled this historic US equities run, while examining the dark side – and potential repercussions – of ongoing corporate buybacks.

Do you want to know when the longest bull market in history will end? Dumb question, right? I mean who doesn’t? Certainly, all those aging Baby Boomers with most of their net worth now in the stock market might have more than a passing curiosity about the great bull’s sell-by date.

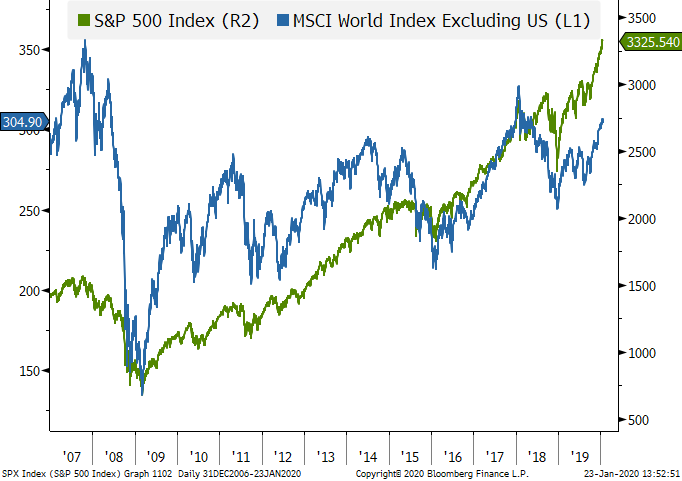

To credibly answer that question, it’s probably worth pondering what has been the main driver of the extraordinary—and extraordinarily singular—run by the S&P 500 since 2009. By “singular”, I’m referring to the fact that US stocks have crushed those from almost any other country. The main international benchmark excluding the US (the MSCI, ex-US) has essentially flat-lined for nearly 14 years.

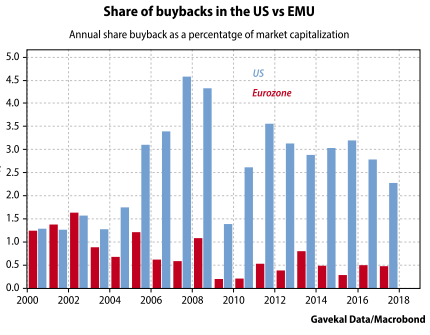

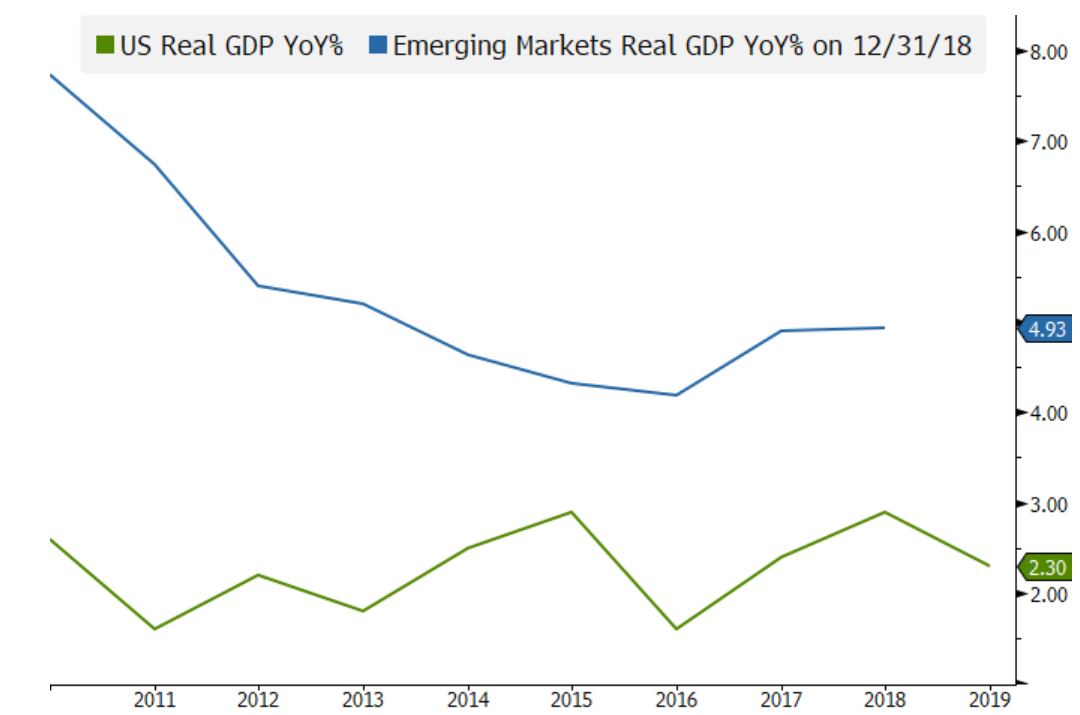

As noted in past EVAs, this is despite, or perhaps because of, the extreme popularity of international stocks, especially emerging market shares, in the early part of the last decade. (Note, per the below chart, how much better those had done up until 2012, from the bear market low in 2009, and then how immensely they have lagged since then.) Perhaps it is mere coincidence that over this timeframe US buybacks have been running much higher than in the rest of the world. Shown below is the US versus Europe but the same is true compared to almost every other country.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

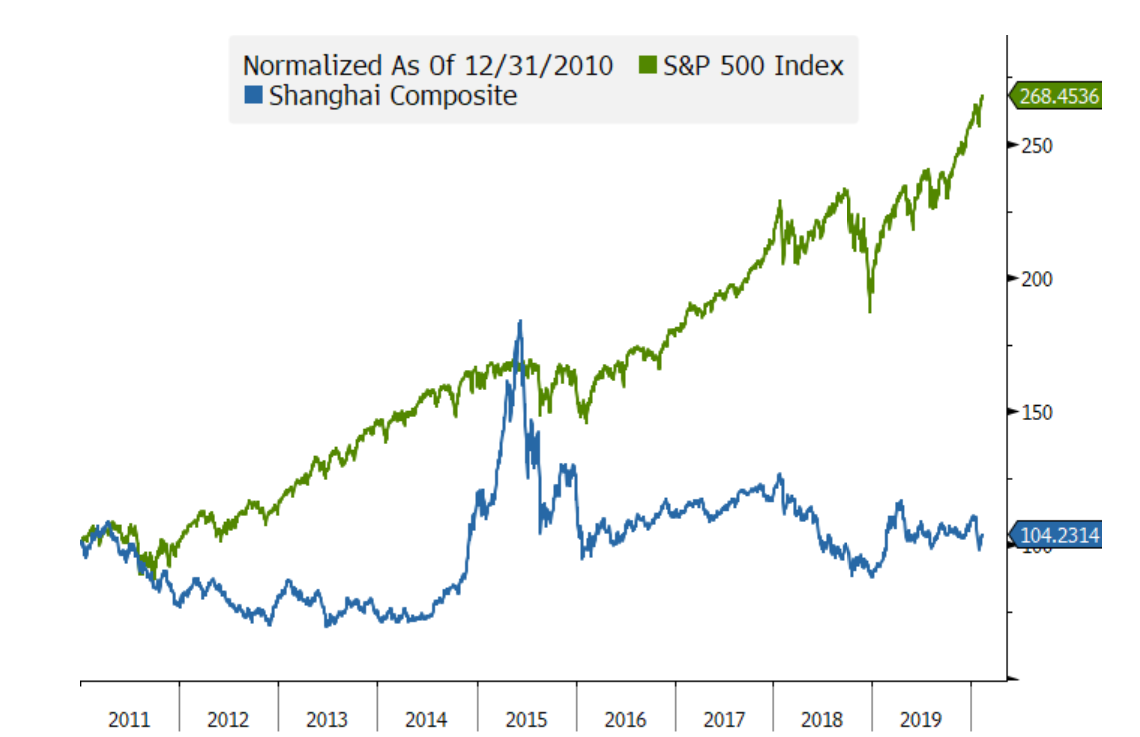

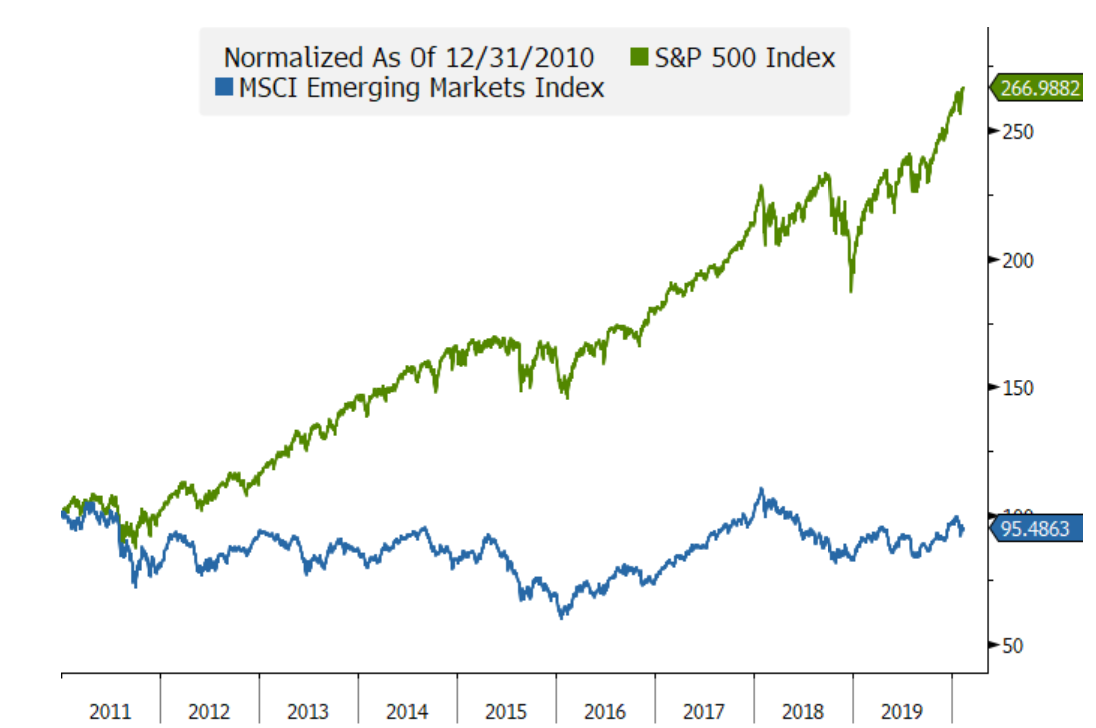

The rallying cry for emerging markets ten years ago was that they offered a “structurally higher growth rate” versus the heavily indebted and increasingly sclerotic developed countries. This included the best of this ossified bunch, the US. The most important developing country for the last thirty years has been, of course, China. And sure enough, throughout the twenty-teens (i.e, 2010 through 2019), its economy grew at an 8% annual rate (with some legitimate questions about the accuracy of this number) vs. just 2% for America, everyone’s new investment darling.

Yet, despite China’s much faster growth—even assuming the real rate was 6% not 8%—its stock market has been a nothing-burger compared to the US. For emerging markets overall, it was largely the same story: superior economic growth and much lower stock market returns.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

This is consistent with a study of 43 countries from 1997 to 2017 conducted by the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority. Its research found, seemingly counterintuitively, that countries with slower economic growth experienced higher stock market returns.

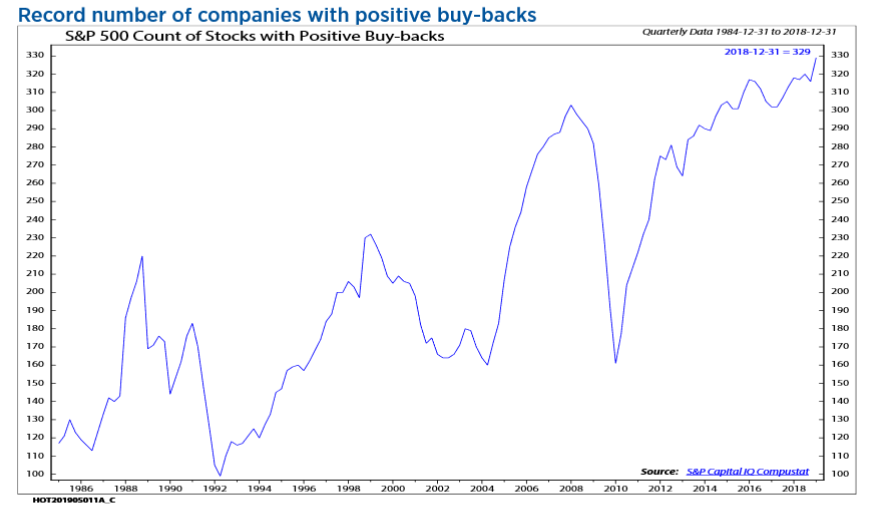

It also discovered that this phenomenon couldn’t be explained by other market-influencing factors such as inflation, currency fluctuations, and profit margins. (The report’s authors referred to these and four other lesser influences as “The Seven Dwarfs”, showing, if nothing else, that Walt Disney’s iconic is culturally relevant even in the Middle East.) The study conceded these dwarfish drivers could influence short-term lags or leads but they tended to cancel out over time. Now here’s the kicker that cuts right to the heart of this latest chapter of “Bubble 3.0”: 80% of the variation was attributable to net buybacks.

A prime reason for this outcome is that faster growing countries need capital to fuel their expansions. This means a combination of debt and equity issuance – or at least it should if a country’s corporations want to keep their balance sheets in order, a point that will be further explored shortly. Ergo, fast economic growth requires large quantities of equity offerings, diluting existing shareholders unless the capital invested earns a satisfactory return. In countries like China, the government often “encourages” investments which are perceived to be good for the nation at large but all too frequently don’t earn much for shareholders. This almost inarguably was a key reason why most Chinese stocks have been such dogs over the past 20 years, despite the economic miracle that country has produced. (This has especially been the case with the big State-owned Enterprises like PetroChina and China Mobile. More nimble and entrepreneurial companies such as Alibaba and Tencent have had rocket rides similar to the US tech stars but they have not been included in the official Chinese stock index.)

In the US, senior management teams have been pikers when it comes to what is typically referred to as “cap ex”. This is despite 2018’s monster corporate tax cut which was supposed to accelerate capital expenditures. In reality, their long downtrend has continued but what has truly exploded is the rate of share repurchases, aka, buybacks.

Source: Ned Davis Research

Source: Ned Davis Research

There is certainly nothing inherently wrong with companies retiring their own shares. In fact, done at low prices, where the effective equity yield is high, they can be extremely rewarding to shareholders. For example, if a company is selling at 10 times its annual profits, its earnings yield is 10%. ($10 of earnings on a $100 market price.) If it can safely borrow money at 4%, or has cash sitting around yielding 1 ½%, buybacks are value-enhancing for shareholders. However, if the P/E is 20, then the earnings yield is only 5% and the benefits become pretty skinny. The latter situation is much more common these days with the S&P trading around twenty times its aggregate profits over the last 12 months.

As the high-profile economist David Rosenberg has repeatedly pointed out, there is a $4 trillion trifecta occurring presently. During the twenty-teens, the Fed has created $4 trillion of – to be blunt – “Bogus Bucks”, or BBs, and those BBs have been used to fund $4 trillion of other BBs, as in buybacks, and yet another $4 trillion has been taken out in additional corporate debt (a third BB, Bubble Bonds?). Kind of a strange coincidence, isn’t it?

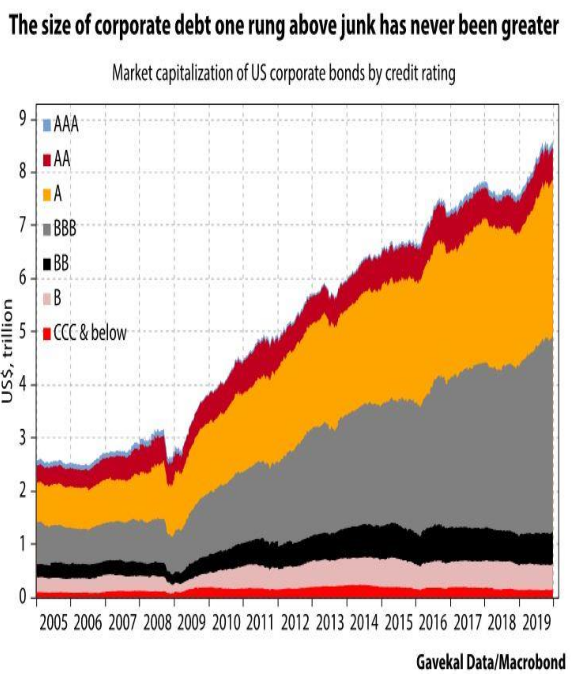

To take the BB play one step further, the largest slice of the corporate bond market, roughly half, is now rated BBB. Thanks to the $4 trillion of buybacks and related leveraging up that has been done, many of these are in grave danger of being downgraded to BB in the next recession. BB-rated is the level considered junk and David Rosenberg estimates that 30% of BBBs actually have a BB-rated credit profile. In other words, they should be rated below-investment-grade now, even before a recession has officially begun. (Please be aware, though, that 2019 saw both an earnings recession—at least two quarters of falling profits—and an industrial recession, with scant media coverage of either.)

To put things in perspective, in 2018 alone companies paid out a combined $1.25 trillion in dividends and buybacks. Per The Financial Times, this is equivalent to the value of all the gold that’s ever been mined (but not quite up to the market cap of Apple!). The dark side of this is that net debt to cash flow is at a 16-year high, as dividend and buybacks have been running above the free cash flow (i.e., excess cash flow) necessary to fund them since 2013.

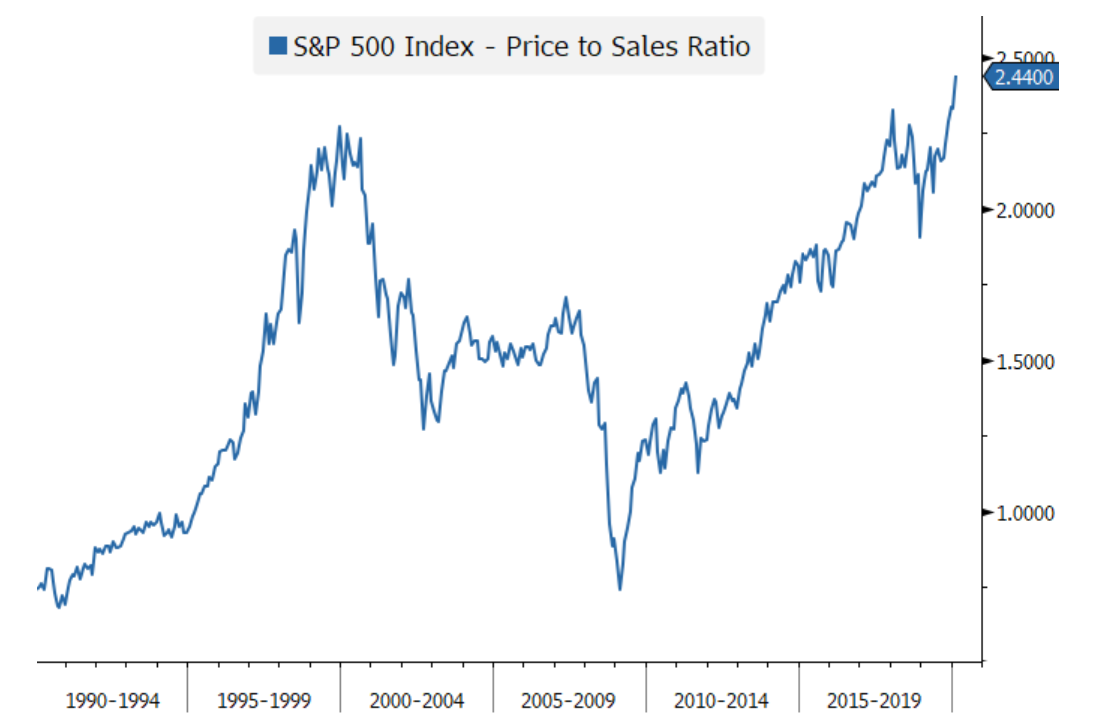

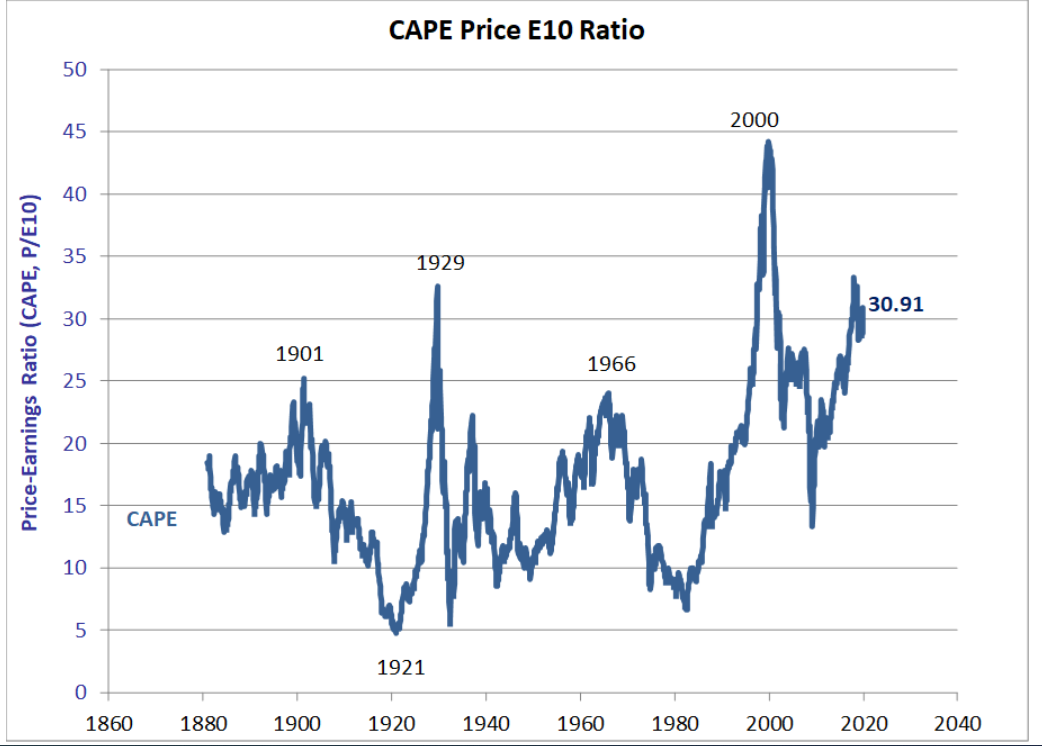

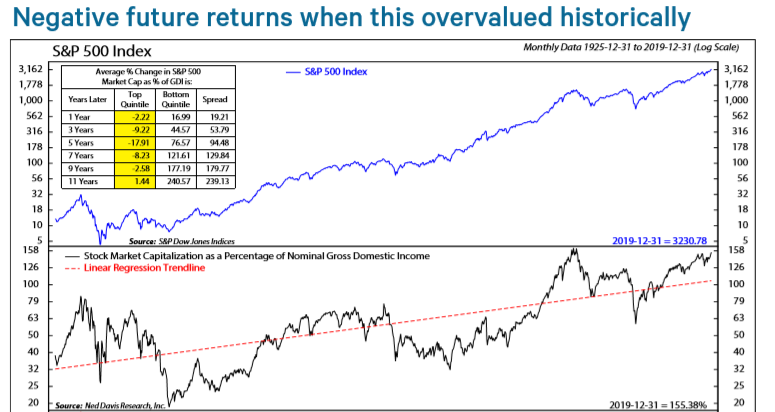

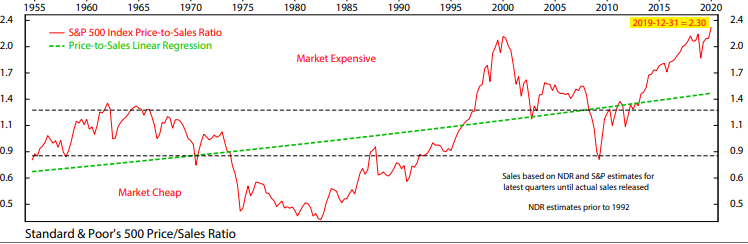

As BofA Merrill Lynch strategist Savita Subramanian has observed: “Buybacks work when there’s scarcity value. Now everyone’s doing it.” To her point, 60% of companies have done repurchases. And they are doing so at a time when the price-to-sales ratio, one of the best metrics for predicting long-term returns, is higher than it was in early 2000 (i.e, the tech bubble apex) and when the Cyclically-Adjusted P/E (CAPE) is around 30. (The latter is also known as the Shiller P/E ratio, named after Yale’s esteemed Prof. Robert Shiller; the good news is it’s not nearly as high now as it was in early 2000, though, compared to all other prior levels it’s extremely elevated, basically where it was in 1929.) Shifting to another tried-and-true measure, stock market returns have historically been negative on nearly a 10-year basis when stocks are this high relative to the size of the economy.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Cyclically-Adjusted P/E (CAPE), aka, Shiller P/E

Source: Online Data Robert Shiller

Source: Ned Davis Research

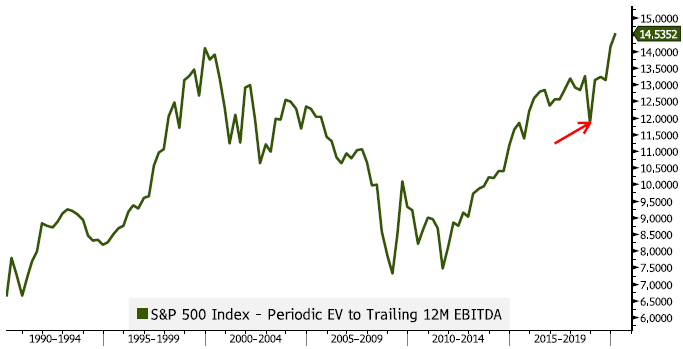

Similarly, the ratio of Corporate America’s enterprise value relative to its aggregate cash flow (EV, equity and debt values combined, to EBITDA, earnings-before-interest-taxes-depreciation-amortization) is at an all-time high. In other words, both debt and equity levels/valuations are extremely elevated. As noted at the outset, prudent companies are careful not to let their debt/equity ratios get out of line even when spending on growth initiatives. Sadly, prudence has been increasingly MIA in corporate boardrooms in recent years.

To elevate debt to dangerous levels to enable share repurchases—which usually lowers profits because of the increased interest costs—is the antithesis of judicious corporate stewardship. Again, this likely won’t become an issue until the next recession—a full-blown one, not just of the earnings and industrial variety. But when that occurs, the trap door will fly open and the plethora of corporate bodies left twisting in the wind will be a gruesome sight.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

When companies are repurchasing shares at one of the highest levels ever relative to the size of the US economy, and also compared to cash flow, they are almost certainly destroying long-term value for their shareholders. Even though this won’t be obvious for years in the overall market, we’ve already seen sneak-previews of the coming horror film. As covered in prior EVAs, GE has been a badly tarnished example of this; it bought back tens of billions of stock at much higher prices and has been forced to issue equity at depressed levels to strengthen its now precarious financial condition.

Mining and energy companies did the same thing. They were aggressive buyers of their own shares during the boom years of the early twenty-teens. After each industry’s bust, many were forced to sell shares on the cheap to shore up their weakened balance sheets.

For all of you Northwest-based EVA readers, our local aerospace juggernaut, Boeing, is another case study in mis-managing buybacks. Fortune Magazine, certainly no foe of big business, pointed out in an article this month that since 2013 Boeing has splurged on $43 billion in repurchases. This is in contrast to just $15.7 billion spent on research and development (R&D) for its commercial aircraft division. The article asserts part of the blame for the 737 Max fiasco – which has already cost the firm $9 billion, a tab that is almost certain to rise much higher – was due to the diversion of resources to buybacks. Now, Boeing appears to be on the verge of compounding its previous errors by borrowing money to pay dividends at the same time that it is reducing R&D spending.

As many have noted, including Efficient Frontier Advisors’ William Bernstein, companies are notorious for their buy-high, sell-low tendencies. Because the normal bull/bear market cycle has been distorted by the Fed’s four QEs, the 2018 corporate tax cuts, and trillion-dollar federal deficits, the day of reckoning, when it is revealed how much over-paying has occurred, has been postponed. Be assured, however, that it’s a case of postponement, not cancellation.

There are those who contend trillions of share buybacks haven’t been the main propellant of this perpetual motion bull market. They insist rising earnings and profit margins have been the key. Undoubtedly, there is truth in that, especially when it comes to the big US tech companies which are beneficiaries of the “network effect”. These included firms such as Apple, Google, Facebook, and Microsoft, where users become either locked-in or quasi-addicted to their services. The cost of acquiring new customers is very low; thus, incremental revenues from adding each new user flows almost totally to the bottom-line.

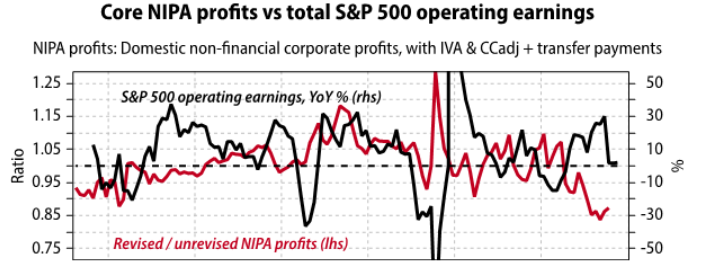

Revealing the disparity between those with a network-effect and the rest of corporate America, the broadest measure of economy-wide profits is the NIPA, or National Income and Product Accounts. We’ve run this before but it’s worth reexamining. You can easily see the contrast compared to S&P profits which have been materially boosted by the tech titans’ earnings.

Source: Gavekal

The reality is that very few companies possess the network-effect, high-margin, and rapid-growth profile of the companies often referred to as the FANGs or FANGMs (Facebook, Apple, Netflix, Google, with Microsoft added in the less catchy second version). Thus, outside of this elite group, most of which have trillion-dollar market valuations, profits have been stuck in the mud for years. Ominously, this has happened despite the longest—though slowest—economic expansion in American history.

In addition to tech being the star of the earnings show, it has also been the headliner in the buyback bonanza. However, there is a dark side to this situation. The fact of the matter is that there has been precious little actual share count reduction for all the trillions expended on repurchases. The tech industry is notorious for lavish options and stock award packages (especially for senior management, of course). As Barron’s reported on this in October of 2018 (and is even more true today): “Some market critics like to say that large corporations are cash-management machines for executives. In other words, companies buy back shares, put them into their treasury, and artificially boost earnings per share. Often, they aren’t all retired and a portion of them return to the pool of outstanding shares via executive stock compensation.”

Consequently, despite expending the aforementioned $4 trillion on repurchases, Corporate America has only retired about 0.7% (be sure to note the zero-point!) per year of the S&P’s share count over the past decade. Said differently, $4 trillion of buybacks has amounted to at least 20% of the market capitalization, yet the share count has only come down about 8%. Where did the rest go, you might wonder?

Ben Hunt is one of the most iconoclastic newsletter authors I read (and he’s got a lot of competition in my world!). Ben recently wrote a piece called “The Rakes”, after the name given to the person in a poker game who skims off a small portion of each betting pot. His short essay is a scathing take-down of the buyback mania and he shines a bright, revealing light on the magnitude of the corporate “rake”. This is basically the portion of a repurchase program that goes to insiders.

Even at some of America’s most iconic and well-run companies, “the rake” amounts to 25%, or more, of shareholder sums expended. Ben singles out one of my heroes in life, something I refuse to do, especially because this is simply the way things are done in the terminal stages of Bubble 3.0.

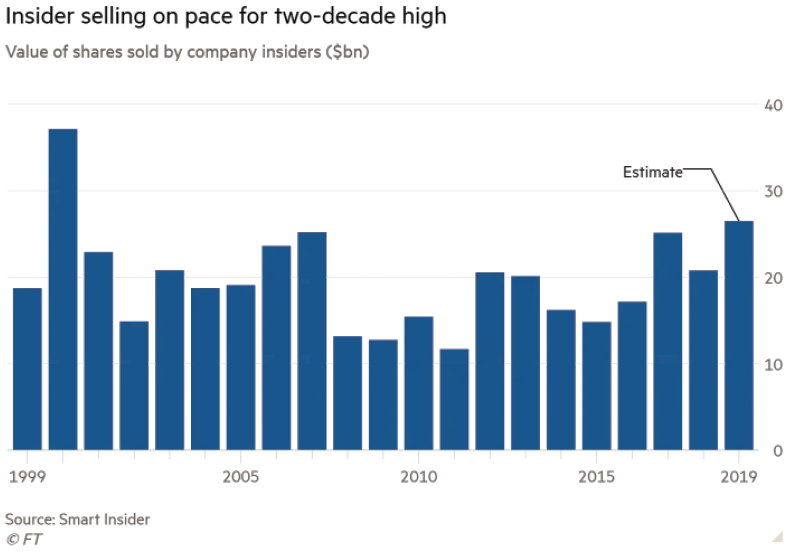

If this isn’t blood-boiling enough, let me share some other relevant factoids on this issue. The SEC has found that insiders sell five times as much stock in the eight days after a buyback announcement relative to ordinary days. Twice as many insiders also dispose of shares in the wake of repurchase declarations. Even more infuriating, the House Financial Services Committee has found that some companies announce buybacks they have no intent of fulfilling in order to juice the stock price just prior to insider sales.

The big picture view of this situation is that we have companies repurchasing their shares at a fever pitch while insiders are dumping said shares at an equally feverish rate.

The fact of the matter is a seemingly endless bull market is a marvelous, though ultimately impermanent, immunization against the various viruses effecting the US economy and financial markets. When everyone is making plenty of money, why be a spoil-sport (unless you’re a congenital contrarian such as moi)?

Now, you might think that “rake” is acceptable if it’s distributing wealth to the rank and file, like through an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP), as well as those at the top of the corporate pyramid. That would be nice, but in the case of this great American company, 97% went to senior management. Because of this entity’s remarkable success in a difficult industry, perhaps this was justified. However, the painful truth is that this happens even at mediocre companies that make up the overwhelming majority of the aforementioned broad profit composite (NIPA). As we’ve seen, this primary measure of America’s corporate net income has pretty much flat-lined since the end of 2012.

Ben’s note has this concise summation of the set of circumstances we’ve seen over the last decade: “One day we will recognize the defining Zeitgeist of the Obama/Trump years for what it is: an unparalleled transfer of wealth to the managerial class. Not founders. Not entrepreneurs. Not visionaries. Nope…managers. Fee takers. Asset-gatherers. Rent-seekers. Rakes.”

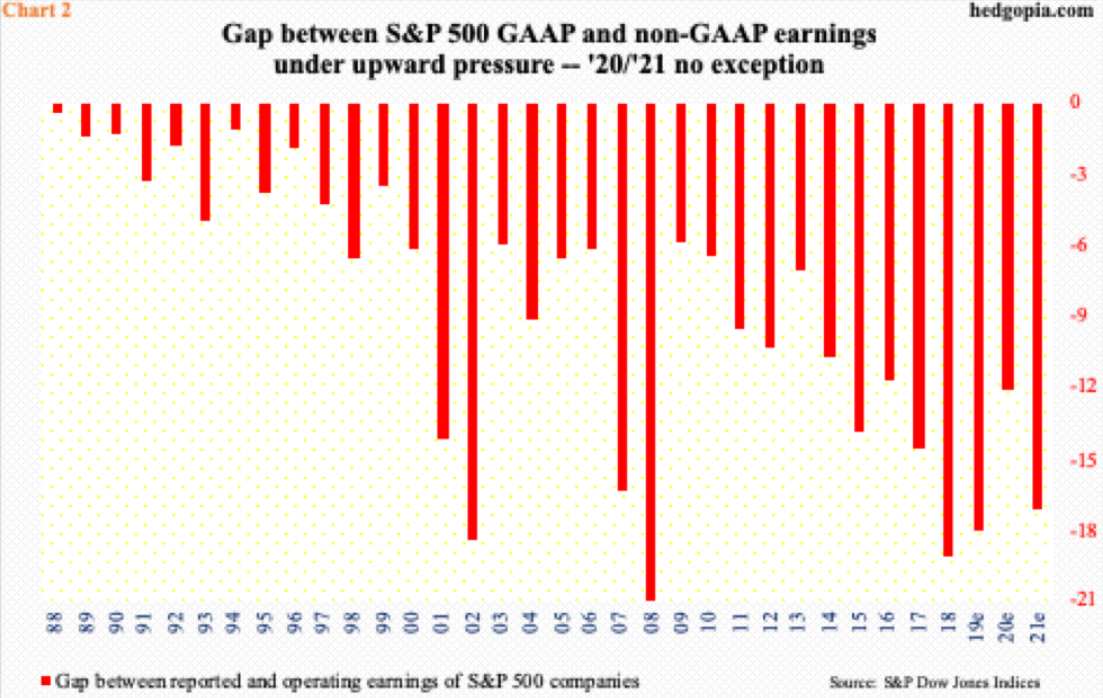

Another gifted newsletter writer is Jess Felder, who recently penned (keyboarded?) a piece called: “Are We Witnessing Another Corporate Earnings Bubble?” (Note the word: “another”.) One of his key points is that the composition of the S&P 500 is different than the overall economy. Highly profitable companies such as tech, financials, and energy (not sure about that last one, at least lately!) are much more heavily represented in the S&P than in the “real world”.

But another leading factor in the divergence is the differing treatment of those pesky stock options that rake off so much shareholder wealth toward senior management. In Jess’ words:

“GAAP accounting, which S&P 500 companies use, allows for a stock option to be granted and then expensed over time using the value of the option at time of the grant. NIPA accounting only expenses the option once it has been exercised, usually at a much later date and with a much higher expense.

The ‘large discrepancies’ between corporate profits and S&P 500 profits then can probably be explained, in part, as a product of the difference in using tax accounting and using GAAP accounting for stock options. Tax accounting has resulted in a much larger expense than GAAP accounting in recent years simply because the value of the options have grown a great deal along with stock prices over time.

These two explanations in tandem probably help to explain why we saw a similar gap in the earnings measures back in 2000. Similar to today, the index had become crowded with ‘high quality’ and ‘growth’ names while many “bricks and mortar” or “value” companies had fallen out of favor and thus out of the index. At the same time, a roaring bull market boosted the value of stock options that served to reduce NIPA profits when they were exercised and inflated the value of GAAP profits by reducing tax burdens (in addition to the preferential accounting treatment).

In short, it seems that the boost in earnings over the past few years in S&P 500 profits could be, to a large degree, merely a product of the bull market rather than the other way around. Investors have crowded into a smaller number of firms that have inordinately benefitted during the current cycle and, in part, due to this crowding, these same firms have been able to report even greater profits by way of a quirk in stock option accounting.

The question investors should now be asking is this: ‘Is this recent earnings trend sustainable or is it merely the product of an equity bubble?’ As the 2000 experience shows, it’s more likely to be the latter.”

Based on the above, it’s reasonable to conclude that GAAP earnings are overstated. If so, this means the market’s P/E is understated—and it’s already among the highest of all-time. Perhaps that’s why there is such a disconnect between a P/E ratio that’s high but not record-breaking and the median price-to-sales ratio that is far above even early 2000, the peak of the greatest equity bubble ever.

It’s even more disconcerting to realize how many companies spoon-feed non-GAAP earnings numbers to the investing community. Some cynics, like this author, consider those to be profits excluding all the bad stuff. The gap (sorry) between GAAP and non-GAAP has been widening in recent years, as it always does late in an economic and market cycle.

Returning to the opening of this “Bubble 3.0” EVA, what might be the death-knell of buybacks? For sure, the highest corporate debt levels relative to the size of the economy are a possibility. However, it would probably take a spike by interest rates, a recession, and/or a surge in defaults to stop this insider enrichment process.

Another more immediate threat might be political. Pols on both sides of the aisle have buybacks in their crosshairs. Unsurprisingly, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have railed against them. But when you hear someone like the GOP’s Marco Rubio saying things such as:

“The justification for corporate buybacks is a company has no better investment available. This may be true for any company from time to time. But what does it say when it is true for many companies year after year? Since 1980 (there has been) a trend of corporate profits flowing back into financial markets and less of these profits invested in increasing productivity through innovation, technology, equipment, etc.

The result is not enough increase in productivity, growth, or widespread prosperity. The argument buybacks are good because (they free up) money to reinvest in other businesses growth isn’t backed up by the facts. Over the last 40 years money back to shareholders has tripled as a percentage of GDP but investment into businesses has dropped by 20%.

Right now, (we) don’t have a ‘free market’. We have a tax code which engineers the economy in favor of inflating prices of shares at the expense of future productivity and job creation.”

Whoa, and you thought I was hard on the prevailing corporate enrichment scheme! Please note the word “future” in Senator Rubio’s closing sentence. What’s tragic today is how few people of influence—be they in politics, central banking, big business, or the financial markets—think enough about the future. Rather, it’s totally about the next election. Or it’s about keeping asset prices levitating to forestall the economy’s natural cycles, not to mention making senior executives obscenely wealthy. It’s all about the now, the future be damned. But the future has a nasty habit of punishing those who ignore the lessons of the past, not to mention the inconvenient truths of the present.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.