"The stock market is the story of cycles and of the human behavior that is responsible for overreactions in both directions."

-SETH KLARMAN, American investor and CEO of the Baupost Group

Since the global financial crisis erupted nearly 10 years ago, central banks have drenched the financial system with more than $10 trillion. One of the many consequences of this gigantic money deluge has been the dampening of cyclicality for both the financial markets and the economy.

Since the US was on the leading edge of this unprecedented stimulus, it’s not surprising that it has outperformed… well, just about everyone. That includes Europe, whose business cycle moved in lockstep with the US over the previous two cycles.

But, this time looks different. With many signs that the US economy is very late in this up-cycle, there are reasons to believe that, relative to the US, European equities provide more upside from here.

One of the main reasons for this is that Europe actually suffered a double-dip recession back in 2012 and 2013 before the European Central Bank launched its own version of QE. Consequently, Europe is at a much earlier stage of the economic cycle than is the US, as reflected in substantial underutilization of both European plants and labor. Unemployment, as an example, remains close to 10% in Europe, a level that would likely trigger widespread social unrest in the US.

As millions of these unemployed Eurozone workers get re-absorbed into the labor force, this will trigger a powerful tailwind for the economy. (In the US, John Hussman has estimated the drop in US unemployment has contributed 1.4% of our roughly 2% per annum growth during this not very expansive expansion.)

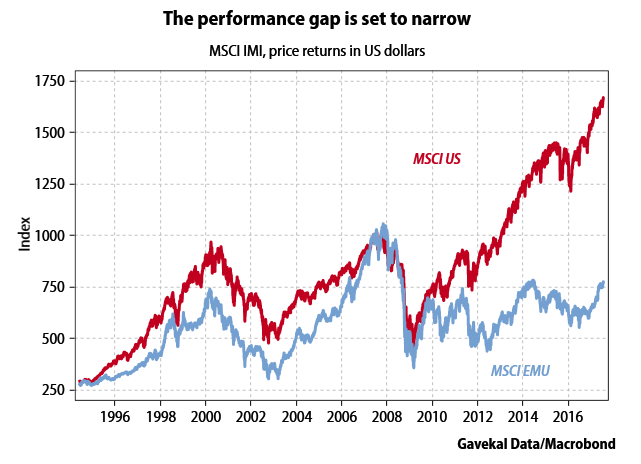

Evergreen wrote extensively about Europe’s long list of problems and threats back in 2011 and 2012, so we are far from Europhiles. But, the reality is that European stocks in US dollars have lagged the S&P by 50% since year-end 2012. Thus, our concerns were pretty reasonable (as was our belief in those days that emerging markets were far too popular and, since then, they have also severely underperformed US stocks).

Moreover, while the Fed is on the verge of a double-tightening (which means that it’s raising interest rates while planning to reduce its balance sheet), the ECB is still in full-blown binge printing mode. This is likely to be more supportive of Continental versus US stocks (though some money will undoubtedly leak over to this side of the Atlantic).

Perhaps the starkest contrast is politically. At the start of this year, euphoria over Trump’s policies was at fever pitch. Since then, reality has bitten—and hard—as we anticipated it would in the immediate post-election timeframe. We also speculated back in January that French stocks would beat the US this year, fueled by the probable election of a popular and reform-minded president, replacing the hapless neo-socialist François Hollande. As we’ve admitted, we were half right. Instead of another François, as in Fillion, 40-year old Emmanuel Macron was elected. His popularity and youthful optimism have allowed him to achieve a dominant majority in the French parliament. He's also forged a strong bond with other European leaders, especially Germany’s Angela Merkel. As a result, confidence and unity throughout Europe are making a comeback worthy of Roger Federer (another European fixture who was assumed to be ready for the ash heap).

So far, our anticipation of French stocks besting the US, at least in dollars, is clearly playing out. But we think that trend has much further to go after so many years of France, and the rest of Europe, playing the caboose to the US market train.

Yet, we also believe a correction is looming for global stock markets. If and when it happens (we definitely think it’s a case of “when”, not “if”), Evergreen will look to add to overseas stocks. Even if the S&P were to fall 15%, US shares would still be very generously valued. But if Europe comes down 15%, some actual long-term bargains would be on offer.

For whatever reason, corrections—or worse—frequently happen in the fall. Should this year follow that pattern, it could be Christmas in October for cash-heavy investors.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

THE EUROZONE IS NOW SO FAR BEHIND THE US, IT'S IN FRONT

By Cedric Gemehl and Tan Kai Xian

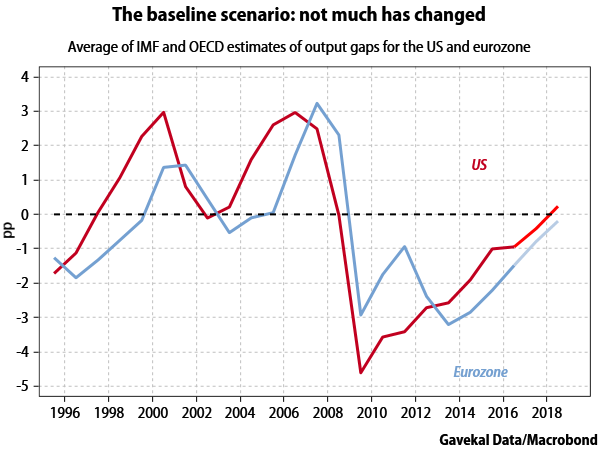

Among the many tricky tasks facing investors is to determine the relative positions of the US and eurozone economies in their respective business cycles. Over the preceding two cycles—the ones that peaked in 2000/01 and 2005/06—the two economies moved broadly in phase, with the eurozone lagging the US by around one year. Estimates from the International Monetary Fund and OECD suggest that that relative position is largely unchanged, with the eurozone trailing the US by one to two years. However, there are good reasons to believe that this time around the eurozone’s lag is much longer—perhaps four to five years— and that the world’s two biggest economies are now moving out of phase.

It makes a degree of intuitive sense that the eurozone should have fallen further behind the US in its cycle. While the US has enjoyed a slow and steady recovery since 2010, the eurozone slumped back into a double dip recession in 2012-13. But to get a clearer, more evidence-based, picture of where the two economies stand in their business cycles, we need to examine the extent of the output gap in each, and assess the trajectory of Federal Reserve and European Central Bank monetary policies.

The starting point for any analyst trying to work out where an economy is in its cycle is to look at the output gap. This measures the difference between actual and potential output. A negative output gap signals that there is slack in the economy—slack which tends to exert disinflationary pressure. In contrast, an output gap moving into positive territory signals that the economy is operating above its potential, a state of affairs which fuels accelerating inflation.

The chart above shows an average of the IMF and OECD estimates for the output gaps in each of the US and the eurozone. It suggests that the US output gap will close this year, while the output gap in the eurozone will close either in 2018 or 2019. If this view were correct, it would suggest (i) that the US economy still has some room to expand before it starts to overheat and (ii) that the eurozone is lagging the US by between one and two years. In other words, this baseline scenario derived from IMF and OECD estimates implies that the relative cyclical position of the US and eurozone economies is little different from that seen in the previous two cycles. We beg to differ.

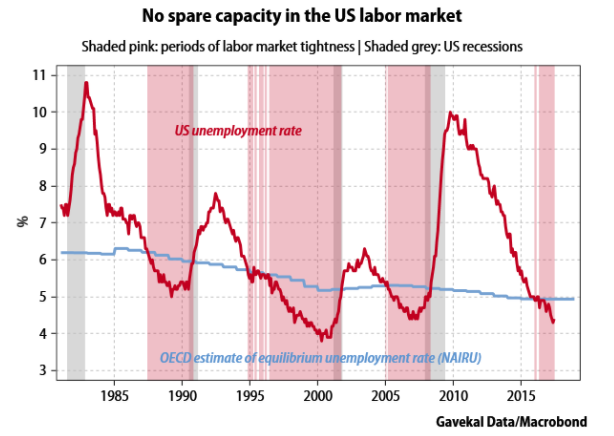

The US: Less than Meets the Eye For several reasons, we suspect that the IMF and OECD measures of the US output gap are misleading, and that the US economy is probably already running above its potential.

First, the unemployment rate has fallen sufficiently below the natural rate of unemployment to suggest that the US labor market is increasingly tight. The gradual slowdown in the growth of non-farm payrolls and emerging, albeit modest, wage pressures appear to bear this out. It is true that the proportion of the working age population outside the labor force has grown in recent years, which could in theory provide a reservoir of spare labor for the economy. However, we doubt that many of these people intend to reenter the labor market, as they consist largely of well-to-do baby-boomers who have opted out of the rat race rather than of “discouraged” workers.

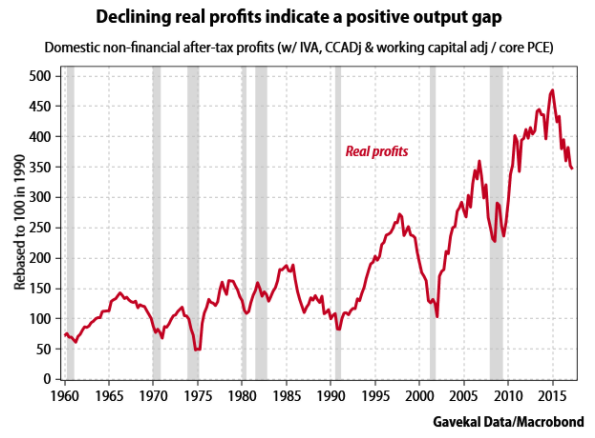

More importantly, assessing the business cycle through an Austrian school lens, falling real corporate profits in the US are partly a reflection of a positive output gap. The idea is that when inflation picks up as more and more resources are utilized, businesses tend to underestimate the increase in cost of replacing capital, which depresses real profits.

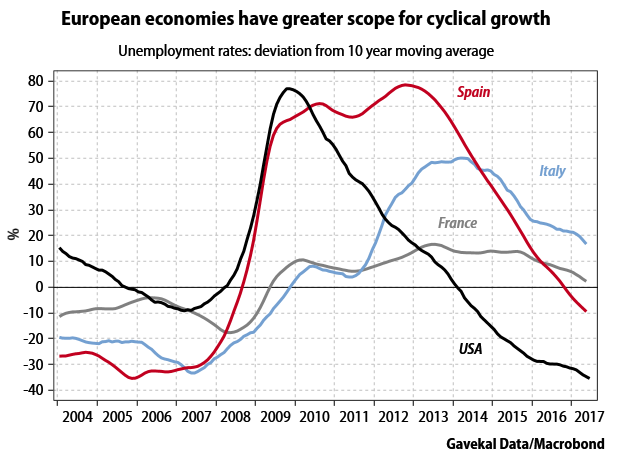

The Eurozone: Slack to Spare In the eurozone, in contrast, our contention is that the output gap remains deep in negative territory, mostly because of the large amount of slack in the labor market. Granted, unemployment rates have fallen throughout the single currency area as economies have returned to growth. From a peak of 12% in 2013, the headline eurozone-wide unemployment rate fell to 9.3% in May, the lowest in eight years. But the headline rate, calculated using International Labour Organization methodology, is a narrow measure of labor underutilization. Using broader measures of unemployment, which factor in discouraged workers and the underemployed, the rate of labor market underutilization in the eurozone rises from 9.3% to 18%. This additional layer of slack in the eurozone labor market helps to explain the near-absence of wage pressures. At 1.5% year-on-year, job creation is now running in line with its pre-crisis average. But eurozone workers have yet to see this strength reflected in their pay packets. As the chart below shows, nominal wage growth has stabilized at around 1.3% year-on-year, not far off its lowest level since the introduction of the euro. It took the US economy almost eight years of growth to reabsorb the post-crisis slack in its labor market. Considering the eurozone only returned to growth at the end of 2013, it could potentially take another four to five years before nominal wage growth starts accelerating appreciably and adding to inflationary pressure.

Divergent Policies The different positions of the US and eurozone in the economic cycle are directly reflected in the divergent monetary policy stances of the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank. Despite the recent slowdown in inflation and diminished prospects of fiscal and regulatory reforms, the Fed is still signaling its intent to tighten. At its last meeting, the Fed hiked short term rates by 25bp and detailed plans to shrink its balance sheet. If the Fed maintains its course— which it is likely to, barring a slump in growth—US money supply growth is likely to slow from here.

Across the Atlantic, the ECB is only now beginning to think about scaling back its extraordinary monetary stimulus. However, with ECB officials highly conscious that the inflation outlook remains subdued even as growth has picked up, any normalization of central bank’s extraordinary loose monetary policy will be very gradual. This suggests the ECB’s situation today is comparable with the Fed’s position in May 2013. If so, then the ECB is lagging the Fed by some four years.

In sum, in the US the long Goldilocks era of stronger economic activity, modest inflation and easy financing conditions is finally drawing to a close. With little cyclical fuel left in the tank, it will likely require either fiscal stimulus or productivity-enhancing structural reforms to procure a further acceleration of US growth. Given the political dysfunction in Washington, neither looks probable. As hopes for lasting tax cuts, deregulation and stimulative infrastructure spending have faded, so have inflation expectations. US breakeven inflation rates are now back below their immediate pre-election level.

In contrast, the eurozone is only just entering its own period of “not too hot, not too cold” economic growth, with plenty of cyclical scope for a further pick-up in activity without a corresponding rise in inflationary pressure. Moreover, Europe is better positioned politically to deliver structural reform. Admittedly, reformers face an uphill struggle in Italy. However, the election of Emmanuel Macron as French president bodes well for reform in the eurozone’s second biggest economy.

As a core plank of his policy agenda, Macron has pledged to reduce the weight of the state in France’s economy and to liberalize the country’s infamously rigid labor market. And despite a plunge in his approval rating following an unseemly spat last week with France’s most senior general, the probability remains good that he will be able to succeed where his predecessors failed. If he can, his progress could help open the way for meaningful reform at the eurozone level.

Conclusion The eurozone economy offers brighter prospects than the US in terms both of cyclical upside and of structural improvements. As a result, we expect the big gap in equity performance that has opened up since 2010 to start closing. Consequently we recommend an unhedged overweight position in eurozone stocks. This is not to say that euro-area equities will be immune to a big sell-off in Wall Street should the US economy tip into recession. But while we think such an eventuality to be likely over the coming years, it is not yet imminent. In the meantime, eurozone equities are well placed to outperform.

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.