“Most investors are not well-equipped for an analysis of that kind (political risk). They built their careers crunching numbers, not pondering social science.” -The Financial Times’ GILLIAN TETT

“The roughly $275 billion in legal costs for global banks since 2008 translates into more than $5 trillion of reduced lending capacity to the real economy.” -MINOUCHE SHAFIK, deputy governor of the Bank of England

-Could Congress create consecutive crises? Before answering this question, was it complicit in the housing fiasco and the resulting global financial crisis?

-Between the Community Reinvestment Act (forcing banks to issue high-risk mortgages), the Glass-Steagall repeal (allowing them to enter riskier non-banking related areas), failure to reform Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (both took on enormous credit risk on a small capital base), and congressmen and women like Barney Frank (who publicly stated he wanted to “roll the dice on housing”), the answer in this author’s mind is a resounding yes.

-This time, Congress has used the Fed’s Big Easy monetary policies as an excuse not to enact crucial reforms. But, while it has had reform paralysis, it has been hyperactive in creating new regulations (560 additional major new regulations in the past 8 years).

-Small businesses are particularly vulnerable to this regulatory onslaught.

-Perhaps even worse, Congress is now proactively attacking the private sector. A key example has been the strident attacks on one of America’s best banks: Wells Fargo.

-Wells clearly made mistakes, but the total cost to consumers was around $2 1/2 million. Calling it a “criminal enterprise” and “a school for scoundrels”, as some in Congress did, seems way over the top, especially for a mega-bank that was one of the few not needing a bail-out during the financial crisis.

-It’s almost certain that there will be more companies and senior management teams called on the congressional carpet, with huge fines and more regulations heaped on the private sector. This is becoming a major drag on growth.

-Some in Congress obviously hold capitalism—and, especially, capitalists—in very low esteem. Unfortunately, this attitude seems to be spreading, despite the collapse of numerous socialistic systems around the world.

-The stock market is ignoring this escalating governmental hostility, as it is with so many other risks.

The 5 Cs—Could Congress Create Consecutive Crises? Sorry for the admittedly hokey mnemonic but aren’t all of those memory tricks kind of that way? Most of you probably remember the old algebra version for the orders of operation: Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally (powers, exponents, multiplication, division, addition, subtraction). Fewer, but no doubt some, will recall the similar trigonometry mnemonic, Soh Cah Toa.*

Math isn’t your gig? Well, it’s not mine, either, but I force myself to study it anyway, and I have to admit it’s a late-in-life “acquired taste”. But when it comes to politics, there’s no up-there-in-years growing appreciation of our government and its ways. In truth (a quaint notion, long banished from the halls of Congress), the older I get, the more I am appalled by our country’s sickening descent into tastelessness and, even worse, ever increasing irrationality. Moreover, on a daily basis, it’s becoming virtual-reality clear that the victim of this near-insanity is America’s private sector. It’s an escalation of the extreme—and extremely toxic—meddling with the economy’s ecosystem Congress has been engaged in over the last fifteen years or more.

Let me defend my foregoing tirade. First, I need to make a case for my belief that Congress played a leading role in the 2008 disaster flick known as the “global financial crisis”. As time has passed, our precious legislative body has sought to pin that debacle on nearly every company and senior management team in the financial services industry. This includes the recent inquisition of Wells Fargo CEO Jon Stumpf, despite the fact Wells was one of the least culpable major banks in that fiasco (more on this topic in a bit). Yet, with a duplicity that is shocking even by congressional standards, the Hill has granted itself a free pass—one that is most definitely not deserved.

First, let’s consider the Community Reinvestment Act. It was first passed in 1977 and, like so many laws promulgated by Congress, the intent behind it had a laudatory objective. It was intended to encourage regulated financial institutions to service the credit needs of the communities within which they operate, including low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. In essence, it was seeking to eliminate discrimination in the extension of loans. The most extreme abuse of this was in the old “red-lining” policies, which blocked lending to perceived dodgy areas.

Suffice it to say that over the years, especially during and in the immediate wake of the early 1990s savings and loan crisis, the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was consistently expanded. This included making a full embrace of it by banks a precondition for regulatory approval of the wave of mergers that occurred in the aftermath of the S&L disaster. In 1999, the CRA crossed paths with what would become, in another eight years or so, one of the most notorious pieces of banking legislation ever passed: the Financial Services Modernization Act.

Never heard of that innocuous-sounding law? In the fullness of time, it proved to be anything but harmless.

Shattering the Glass-Steagall ceiling. Way, way back in 1933, during America’s worst banking crisis, Congress passed the Glass-Steagall Act. This law forced banks out of areas like investment banking and insurance services. It was meant to prevent the conflicts and cross-related risks that were believed to have played a role in the market crash which brought on the Great Depression.

It stayed in place until the late 1990s when Congress, under pressure from Wall Street behemoths like Citigroup, passed the Financial Services Modernization Act. This effectively defanged Glass-Steagall, allowing banks to expand into a wide range of other theoretically profit-making opportunities. But there was one catch.

In order to be allowed to break free of Glass-Steagall, said banking institution would need to agree to be CRA-compliant as it completed its metamorphosis into a full-service financial entity. (Previously, the legislation seeking to abolish Glass-Steagall also sought to require full disclosure of CRA-type deals banks had made with community groups on the grounds these amounted to de facto extortion; i.e., banks were being pressured into making bad loans by special interest groups.)

Therefore, the price to get Glass-Steagall shattered was a further expansion of CRA while blocking examination of the dangers it might be posing to the banking system. Ultimately, the effective repeal of Glass-Steagall was widely believed to have allowed banks into risky areas of the financial markets, further aggravating the impending cataclysm.

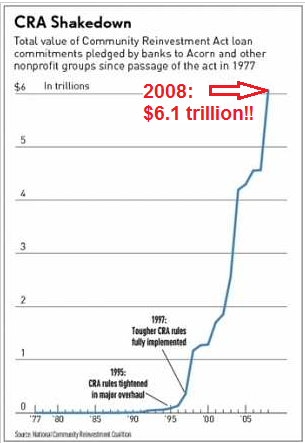

However, the real neutron bomb (where the people are wiped out but the buildings are left standing) was how CRA morphed into sub-prime mortgages. These were, of course, ground-zero in causing the housing bubble and eventual implosion that nearly took down the Planet Earth’s financial system. As you can see on the chart below, the outstanding amount of high-risk loans truly went vertical in the first half of the 2000s, hitting $6 trillion by 2006, on the eve of the collapse.

This is not to say that greed on the part of banks was non-existent. Corporations are in business to generate profits and with the government aggressively egging them on, this had to seem like a no-brainer. This was especially the case since banks were able to package these iffy loans into pools and sell them off to yield-hungry investors (known as “securitization”).

Consequently, the belief was that they had off-loaded their credit risk. Former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan eventually confessed his amazement (and, embarrassingly, cluelessness) that even as banks were furiously selling off these ticking time bombs, their investment divisions were just as feverishly accumulating them.

Also, playing a feature part in this horror film were the Government Sponsored Entities (GSEs), popularly known as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Both were under increasing congressional pressure to insure ever larger amounts of low-income mortgages. They also doubled-down on this soon-to-be indecent exposure by holding such loans in their retained portfolios.

To be fair, not all congressmen and women were blind to the escalating risks.

The lonely voices. Rep. Richard Baker (Lou.) was an early and outspoken critic of the GSE business models. Due to the implicit government guarantee of their debt, both Fannie and Freddie were able to operate with half of the equity required of other lending institutions. Of course, Congress wanted something in return for this implied backing: more low- and moderate-income loans. Fannie and Freddie were happy to comply—as were their shareholders who, for years, enjoyed spectacular returns (both were publicly-traded until their collapse, despite their quasi-government status).

As the sub-prime mania really got rolling in the mid-2000s, Fannie and Freddie were also under pressure from their shareholders to participate even more in the fun and games. They loosened credit scores and began permitting smaller down payments.

Meanwhile, Rep. Baker’s reform efforts ran into the buzz-saw that was the Fannie/Freddie lobbying machine. As this mechanism went into hyper-drive, it was able to overcome efforts by the Bush II administration to rein in its riskier activities. Even Alan Greenspan, whose “beer goggles” view of the housing bubble would eventually tarnish his once maestro-like reputation, attempted to lend a hand in the fight to de-risk Fannie and Freddie. But he wilted under the firestorm of indignation from their supporters. As the Wall Street Journal recently put it: “The housing-industrial complex denounced him for failing to understand mortgage finance and ran devastating TV ads to deter members of Congress from supporting Mr. Greenspan’s calls for regulatory intervention.”

It didn’t require much deterrence for most members of Congress, who, for various reasons, were rock-ribbed (or, more accurately, rock-headed) in the defense of Fannie and Freddie, including the GSEs’ efforts to trash their own lending standards. Among the most infamous examples of this was none other than Barney Frank whose name would—in an ironic twist worthy of Hitchcock—eventually go down in history as a co-sponsor of the post-crisis legislation meant to prevent another disaster, Dodd-Frank. The esteemed representative from Massachusetts literally told the world that he wanted to “roll the dice on housing”. Well, he did, they came up snake-eyes, and the world paid a staggering price for his reckless gamble.

Ok, have I given you enough evidence of the government’s complicity in the last crisis? So, what about the one that I believe is already unfolding?

Killing the golden goose. Prior EVAs have made the case that the Fed’s “Big Easy” monetary policies that have stayed in place for an incredible eight post-crisis years created a series of asset bubbles. The best proof of my contention is that a number of these have already popped, or, at least, have seen a lot of air leak out of them: small-cap stocks, biotech, commodities, high-end art, collector cars, luxury real estate in certain urban markets, emerging market equities and bonds, to name some of the higher profile examples.

The Fed’s monetary incontinence has also enabled Congress to avoid addressing its equally profligate budgetary behavior. As we all know, at least those of us who are looking at the facts, the entitlement crisis is nearly upon us, as even the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office has disclosed. Yet, Congress has done virtually nothing substantive to address it.

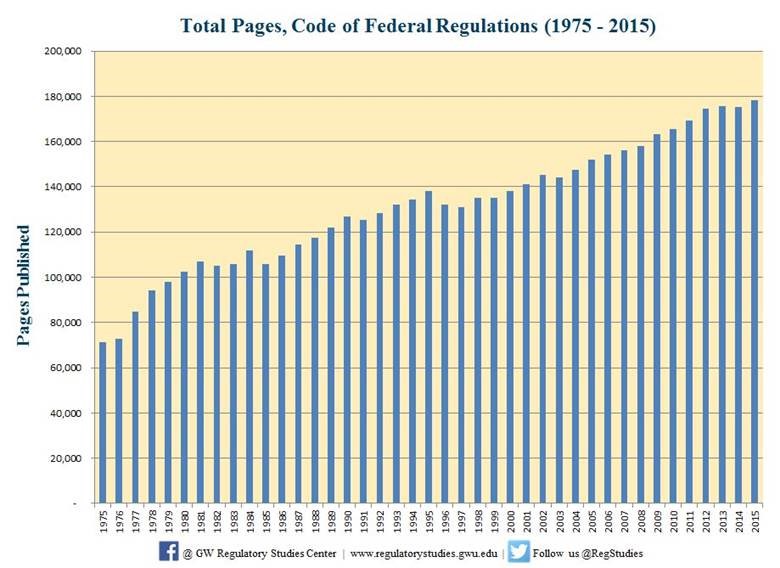

What it has done—on a most hyperactive scale—is continue to pass regulations at a rate that makes your head swim, creating a hurricane-force head-wind for the private sector. The Code of Federal Regulations now runs nearly 180,000 pages (at year-end 2015), up about 30,000 pages from ten years ago.

560 new major regulations have been enacted in the last 8 years, double the amount during the “W” Bush administration. (In fairness, many of these were instituted by the Administration, bypassing Congress, though the most onerous, including Obamacare and Dodd-Frank were approved by the House and Senate.) Smaller businesses are the least capable of being able to cope with this tsunami of dos and don’ts, and they are the primary drivers of job growth. The chart below on the trend of new business formations may be one of the scariest out there in its implication for future employment and economic well-being.

THE SHRINKING PRESENCE OF NEW COMPANIES

But in addition to the regulatory suffocation, there is a rapidly proliferating government-led attack on Corporate America. Virtually every day, another company is being sued for a breach of conduct with enormous fines almost always being assessed. In some cases, the amount requested is so large as to force the company into bankruptcy if, as has been the case, the Feds require a bond to be posted—well before a verdict has been handed down. (However, political pressure on pharma companies that have egregiously raised drug prices is, in my view, completely justifiable.)

If you happen to be a financial institution—even one that aced the ultimate stress-test of the global financial crisis—you’ve really got a sniper light on your head.

Totally Stumpfed. Unlike almost every other major US bank, Wells Fargo managed to navigate the housing crash with comparative ease, almost aplomb. Despite the fact that its home state of California was the epicenter of the monstrous housing earthquake, Wells didn’t need a government rescue (i.e., TARP funding). In reality, it did its best, like JP Morgan, to refuse taxpayer money. But for the good of the system, newly appointed CEO Jon Stumpf accepted the funds (the political pressure for all banks to partake was based on the belief that if only the weak ones did so it would further stigmatize the accepting entities).

Stumpf had been named CEO in 2007, just as the ground was beginning to buckle underneath the formerly booming housing industry. But because Wells had insisted on underwriting its own mortgages, it had used appropriately cautious lending standards. Perhaps this prudent lending was due to the fact it retained most of its originations versus opting for securitization (where the belief was someone else would be left holding the bag). Regardless, Wells got through the crisis without serious damage. This further burnished the image of one of Warren Buffett’s biggest and more famous long-term holdings.

Yet even though Stumpf survived the housing Armageddon, unlike so many of his peers, he was unable to keep his job after Congress got through with him this month. Again, in contrast to his compatriots who never relinquished their lavish pay, despite the collapse or near-collapse of the banks they ran, Stumpf voluntarily returned $41 million to Wells. Certainly, no tears are in order as his total compensation was $250 million since 2000, when his firm first started disclosing senior management earnings. That works out to about $15 million per year, which strikes me as plenty high, though not egregious in today’s world of bloated executive compensation.

In his defense, Wells itself produced nearly $150 billion in after-tax profits since he ascended to the throne, while its market value increased by almost $125 billion. These considerable feats were notwithstanding the worst financial crisis since the 1930s and at the same time that former powerhouses like Citigroup, B of A, and AIG, have all seen their stock prices whittled down to a fraction of what they were in 2007.

This commendable record didn’t stop the Congressional panel from blaming Wells for the housing crisis (nice hypocrisy there), calling it a “criminal enterprise”, and a “school for scoundrels”, among a plethora of similar scathing slams.

Really? A criminal enterprise? Was Wells truly that awful? For sure, their internal controls were weak, they reacted too slowly, they were tone-deaf on how irritating this incident was to the American public, and Stumpf didn’t grovel enough in front of accusers like Elizabeth Warren (who is now making the extraordinary demand of firing the head of the SEC). But they did fire 5300 offenders over a period of years (realize this is out of work force of 268,000), or about 1/2% per year, during the period in question. It does sounds like more supervisory heads should have rolled but the fact is it was the employees who committed the fraud, not the bank, which actually paid out unearned incentive bonuses. The grand total of the bogus fees charged to customers: $2.6 million. Wells has already paid $185 million in fines.

(By the way, this was very much of a bipartisan attack-fest. Some pundits commented that it was the first time in years Democrats and Republicans formed a united front. Great! With all the grave geopolitical and economic threats we are facing, Congress is only able to achieve a spirit of bipartisanship by ripping apart one of America’s finest banks.)

Several years ago, J.P. Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon was hauled before Congress to testify over its multi-billion “London Whale” trading losses. The once revered Dimon, often rumored to be in the running to be named Treasury Secretary, had his reputation severely sullied but he kept his job. His bank ended up paying a $1 billion fine.

Isn’t it ironic that the two CEOs who most successfully guided their mega-banks through the worst financial and economic tempest since the Great Depression, would be treated so savagely by members of an institution that had such culpability for the crisis?

It’s my absolute belief that there are many more companies, both inside and outside of finance, that are destined for a similar fate. The perceived political capital these Congressional men and women are gaining will almost certainly encourage them to keep at it—with seriously negative consequences for our economy at large.

(If you really want to get your blood boiling you might dig into the government’s jihad against ITT Educational, which totally collapsed after demands to put up $150 million as a bond against a lawsuit by federal prosecutors. This was more than it had in total cash, meaning game over—with 4000 employees out on the street and some 40,000 students left high and dry. By all accounts, ITT Educational was a schlocky operator, despite once having a market value of $5 billion. However, it does seem to me they deserved their day in court. Moreover, one of its competitors with worse academic metrics, per the Wall Street Journal, has remained untouched by government prosecutors. It must be just a coincidence that said entity has paid a former US president $17 million over the last six years to be “Honorary Chancellor”, no doubt a most demanding and time-consuming position.)

Let’s close with the investment implication of this escalating war between the sectors…

Bonfire of the inanities. The reality is that political risk is more pronounced than I’ve ever seen in my nearly 38-year investment career. In fact, I don’t believe there’s been another time in American history that has seen the public sector as mobilized against the private sector as it is now. This includes the darkest days of the 1930s, when the US economic model was under assault from the dual forces of fascism and communism. As Gillian Tett wrote in the Financial Times last week, in a smashing article on this topic (show link), “A decade ago…political risk was only something that emerging market investors worried about.” Kiss those days good-bye!

Fortune 500/S&P 500 type companies have the resources to fight this endless series of battles, though profits are likely to suffer—possibly severely—in the process. Financial institutions are the easy targets. They are already staggering under the bureaucratic burden of the Dodd-Frank Act, an 849-page pretzel palace of complexity (the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, in the wake of the Enron and Worldcom accounting scandals, was a mere 66 pages). Additionally, they are increasingly being squeezed out of formerly lucrative business lines. (To see today’s front page article in the Wall Street Journal on this topic, click here.)

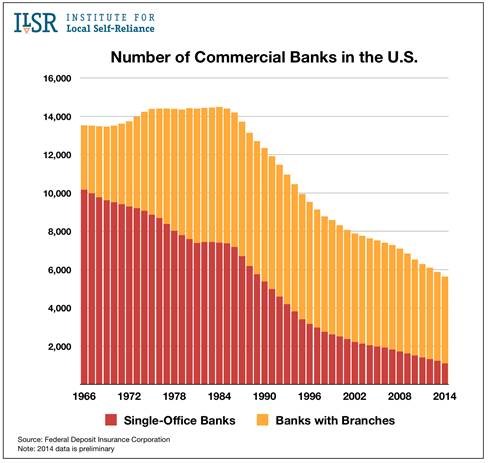

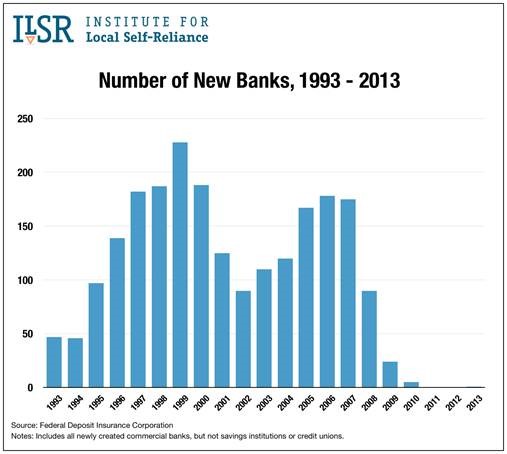

Certainly, making banks less risky is rational but it’s also rendering them less profitable—and less inclined to make loans, an inherently risk-based activity. Community banks, which tend to be the lenders to small businesses, are even less able to cope with the requirements of Dodd-Frank. There’s little doubt this is a key reason why nary a community bank has been started in the past five years. It’s also likely what has caused the number of total community banks to dwindle like insurance companies willing to cover Kim Kardashian’s jewelry.

As we all know—or should—small businesses are the main drivers of job growth. In addition to their dwindling financing options, they are at serious risk from the ever-increasing crush of regulations that squeezes them like they’re being caught between two converging tectonic plates. It’s why I believe there is such a vicious downtrend in new business formations, as seen earlier.

This is especially true if you happen to own, or work for, industries that are viewed as politically incorrect. For example, how many coal companies have survived the last five years? Yes, I know coal is a dirty word and a dirty industry but a lot of middle class Americans lost their livelihoods in the war against that sector (with some estimates that recent legislation will kill off another 125,000 coal-related jobs).

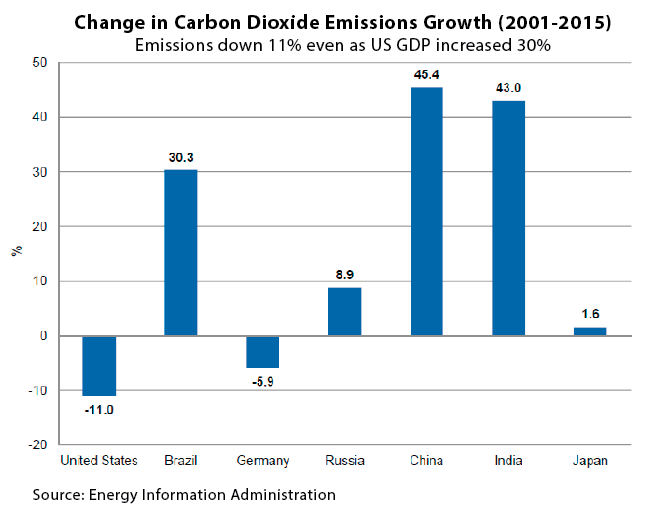

Chillingly, similar tactics are now being directed against oil companies—and even natural gas enterprises—despite the fact that nat gas is such an essential bridging fuel to the time when renewables can carry more of the burden. (The latest tactic is to halt pipeline connections to the new fields, thereby stranding the new production; unlike with oil, gas can’t be railed.) Do we really want to curtail natural gas output, especially since it has helped dramatically reduce carbon output?

Actually, I think for some, the answer is yes. There are many in our government who obviously hold capitalism and, particularly, capitalists in very low esteem. These individuals would like to see far greater control by the State apparatus over the private sector. Every transgression by for-profit individuals and entities is put under an unrelenting spotlight while the truly shocking failures by our political class go largely unexamined and unpunished. Each of these real or imagined errors by the private sector then unleashes another torrent of growth-retarding rules and regulations.

This is a tremendous threat to future economic growth and, in turn, to the long-term earnings outlook for the S&P 500. Yet, the stock market remains serenely oblivious to this risk, as it does to so many others. This is just another in a long list of what many others have aptly referred to as “The Great Disconnect”. To my eyes, it’s getting more and more disconnected every day.

Color me concerned, very concerned. Also, color me an unrepentant capitalist, one who watches the total implosion of State-controlled economies around the world and is incredulous that our political elites are steadily moving us in that depressing direction. It’s about time for an immediate about-face. Any bets about whether that’s going to happen?

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

*Sine: Opposite/hypotenuse; Cosine: Adjacent/hypotenuse; Tangent: Opposite/adjacent. My apologies if that triggered an unpleasant flashback!

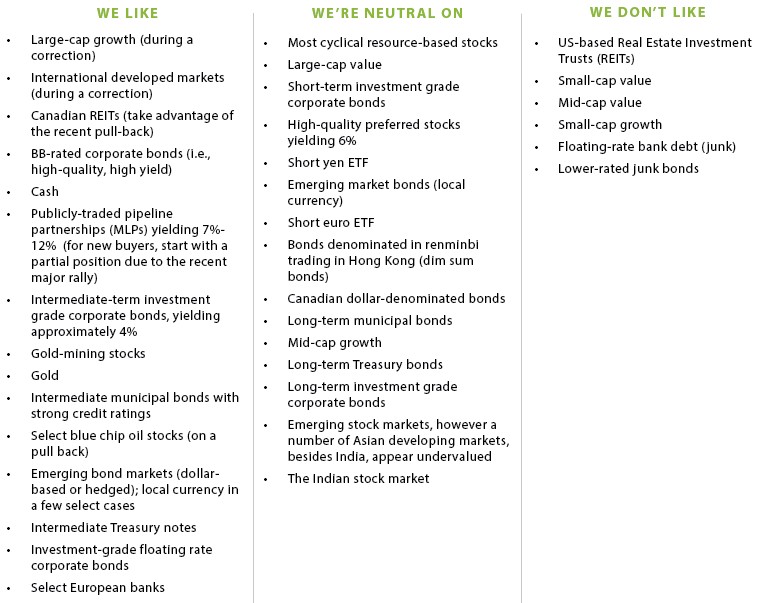

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.