“To combat the depression by a forced credit expansion is to attempt to cure the evil by the very means which brought it about.”

-Economist FREDERICH HAYEK, as relayed by William White in his Adam Smith prize acceptance speech last month.

No BS from the BIS. Few non-professional investors have heard of the Bank from International Settlements (BIS), yet it is routinely referred to as the “central banker for central banks”. Even fewer have heard the name William R. White although Mr. White was essentially the chief economist for the BIS from 1995 to 2008, as well as a member of its executive committee.

The low-profile of the BIS and Bill White is unfortunate since they were among the few prominent members of the financial oversight system that presciently warned of the impending disaster a decade ago. The Canadian-born Mr. White now serves as the chairman of the Economic and Development Review Committee for the supra-national Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Last month, he was awarded the prestigious Adam Smith prize (named after the 18th century Brit considered the father of economics), the highest award bestowed by the US National Association of Business Economists.

This month’s Guest EVA is a transcript of a portion of his speech given upon receiving the Adam Smith prize. In it, he provides a brief overview of the conditions that produced the last crisis. But more significantly, he explains why he believes another—possibly more severe—convulsion is possible.

When people tell me that they are confused by all the conflicting opinions out there—some extremely bullish and others equally pessimistic—my usual response is to suggest they listen to those who got the last blow-up right. As I’ve written before, it amazes me that almost exactly the same individuals who were saying “no worries” back in 2006 are repeating that message today. And those who were raising neon-red flags ten years ago, are, in almost all cases, running them up the flag pole again.

For example, in 2007, Wharton professor and perpetual stock market cheerleader Jeremy Siegel debated Jeremy Grantham, co-founder of $118 billion money manager GMO. In the battle of the two Jeremys from nine years ago, Mr. Siegel argued why stocks were still bargain-priced while Mr. Grantham warned of a major shakeout pending due to the housing bubble, among other concerns. Today, they are back at it, with Mr. Siegel forecasting an on-going bull market contrasted against Mr. Grantham’s, and his firm’s, prediction of many years of flat to slightly down after-inflation returns. Perhaps it’s no surprise, based on past history, but Mr. White comes down very much in the GMO camp, per the last line of our excerpt (you won’t hurt my feelings if you skip right to that part; on the other hand, to read his entire speech, please click on this link. Less technical readers may also want to skip most of the footnotes).

As one who warned of bubble conditions in the late ‘90s (about two years too early, my typical “two and too”!) and again in 2005 (ditto), I can personally attest that pointing out the emperor’s nudity is not a pleasant experience. It’s human nature to want bull markets to keep running and, as Buffett often says, it’s in our DNA to take things to extremes. In Mr.White’s view—and mine—the facts are virtually undeniable we homo sapiens have done it again.

To conclude my intro, I’d like to end with two quotes. The first is from the philosopher-king and thought-leader, Yogi Berra, and the second is from Bill White. As Mr. Berra once said: “In theory, there’s no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.” And per Mr. White: “In practice, ultra-easy (monetary) policy has not stimulated aggregate demand to the degree expected but has had other unexpected consequences. Not least, it poses a threat to financial stability and to potential growth going forward.”

Somehow, the elegant theories of the Fed and the other central banks have failed in their practical application. But that doesn’t mean they will stop practicing their theories anytime soon.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

By: William White1

The global situation we face today is arguably more fraught with danger than was the case when the crisis first began. By encouraging still more credit and debt expansion, monetary policy has "dug the hole deeper". The fundamental analytical mistake has been to model the economy as an understandable and controllable machine rather than as a complex, adaptive system. This mistake also implies that the suggestion that central banks should necessarily reduce the "financial rate of interest", in response to a presumed fall in the "natural rate", is overly simplistic. In practice, ultra-easy policy has not stimulated aggregate demand to the degree expected but has had other unexpected consequences. Not least, it poses a threat to financial stability and to potential growth going forward. Further, "exit" threatens to be delayed in many countries, underlining the dangerous fact that the global economy has no nominal anchor. Much better would be policies, introduced by other arms of government, that would recognize that the fundamental problem is not inadequate liquidity but excessive debt and possible insolvencies. The policy stakes are now very high.

Let me begin by saying that it is a great honor to have been awarded the Adam Smith prize. I am conscious of both the importance of the awarding body and the distinguished list of previous recipients. Perhaps even more important, I recognize that my policy views diverge significantly from what has, at least to date, been mainstream thinking about monetary policy. I thank you for your open mindedness and the opportunity to bring these views to a wider audience. There should be no monopoly on “truth” in this crucially important area, particularly given how frequently and radically views about the conduct of monetary policy have changed over the last fifty years or so2.

It is broadly agreed that the decline in US house prices late in 2005 was the initial phase of the subsequent economic and financial crisis in the United States. Since then all parts of the world economy have come to bear its imprint, with many harboring fears that the Second Great Contraction3 is by no means over. The duration, scope and magnitude of what has happened cannot be explained by a process of contagion. Rather, there were credit driven “imbalances” accumulating in the complex, adaptive system we know as the global economy. The collapse of the subprime mortgage market in the United States, and the complex financial instruments based on such mortgages, was simply the trigger that revealed a prevailing systemic fragility.

In this presentation I will try to trace the origins of the crisis, and the particular contribution made by expansionary monetary policies before (unnaturally easy) and after (ultra-easy) the crisis broke. I will contend that the situation we face in late 2016, both in the advanced market economies (AMEs) and the emerging market economies (EMEs), is arguably more fraught with danger than was the case when the crisis first began. By encouraging still more credit and debt expansion, monetary policy has dug the hole still deeper. Accordingly, I will finish by suggesting some government policies that might be more effective in restoring the “strong, sustainable and balanced growth” desired by the leaders of the G20.

I am aware that the current consensus is that global economic prospects are likely to improve next year. I would remind you, however, that actual outturns have generally been weaker than predicted (as of the previous spring) in each of the last seven years. This is not surprising since the models underlying most forecasts (including those of the Fed, OECD and IMF) do not adequately recognize the vital importance of credit and the financial system. The fundamental ontological error has been to model the economy as a relatively simple machine, whose properties can thus be known and controlled by its policy operator. In reality, it is an evolving system, too complex to be either well understood or closely controlled. Moreover, it is a system in which stocks and “imbalances” build up over time in response to monetary stimulus. This reality makes future prospects totally path dependent, and we are on a bad path.

For the same reason, it is also overly simplistic to suggest that central banks should reduce the “financial rate” of interest in response to a presumed fall in the “natural rate” of interest (the expected rate of return on capital) since the crisis started4. If expected profits have collapsed as a side effect of monetary policies followed in the past, this hardly seems a justification for maintaining such policies. A simple, single period model, stripped of all policy side effects except near-term inflation, is simply not adequate to deal with such dynamic processes. It will be argued below that other side effects, particularly those affecting supply potential and financial instability, demand much greater attention.

Looking at the individual regions in the global economic system also reveals potential weaknesses. The United States is furthest ahead in the recovery but faces declining labor participation rates and (like others) weak capital investment. With “potential” lower, the risks of inflation are higher. Europe faces its own idiosyncratic problems, not least a still weak banking system and potential fallout from the vote on Brexit. Japan is conducting an unprecedented experiment with “Abenomics”, but inadequate results to date suggest even greater experimentation going forward. China must make a transition to a different growth model, based on internal consumption, but all transitions are difficult and carry significant risks.

Moreover, in our increasingly integrated global economy, problems anywhere will quickly become problems everywhere. As an example, think of the implications of China’s slowdown for other emerging markets and beyond, particularly for commodity producers. Note too that the EME’s have expanded markedly in recent decades and developments there are now likely to have a big effect on AME’s. In sum, there are valid reasons for concern about the prospects for the global economy.

How did we get into this mess? I want to suggest that monetary policy, guided by flawed theory, has played a big role even if other agents also contributed materially5. The flawed theory is, essentially, that growth and job creation deemed to be inadequate are solely due to inadequate demand and that this can always be remedied with expansionary monetary policy. Moreover, it is assumed that such policies do not have significant undesirable side effects. They are, therefore, the proverbial “free lunch”.6/sup>

This theory was first tested in the early 1960s, when people still believed there was a long-run tradeoff between unemployment and inflation. However, one significant side effect of monetary stimulus soon revealed itself. The expected “slight” increase in inflation turned into the massive inflationary pressures of the 1970s, as predicted by the theoretical insights of Friedman (1968) and Phelps (1968). The Volcker regime of the early 1980’s dealt with this problem, but the tendency to turn to “easy money” as a cure-all soon reasserted itself.

The “Greenspan put” that followed the stock market crash of 1987 was followed by similar episodes of sharp monetary easing in 1991, 1998 and 2001. Moreover, periods of monetary easing were never matched by symmetric restraint when the economy was recovering. As a result, nominal interest rates ratcheted downwards over the years and debt levels, both public and private, ratcheted up7. These monetary policies were made possible by the persistent downward pressure on global inflation arising from the process of globalization and the return to the market economy of China, the countries of Central and Eastern Europe and many others.

The principal analytical mistake made by domestic policymakers in the AMEs was failing to recognize the importance of these positive, global supply side shocks8. Disinflationary pressures ought not to have been interpreted as indicating the need for ever increasing domestic credit expansion. On the one hand, this outcome was a byproduct of excessive fears about the negative effects of deflation9. On the other hand, it reflected an underestimation of the costs associated with easy money, in particular the buildup of a host of other imbalances in the domestic economy. In the successive cycles noted above, monetary easing generated “rational exuberance” which then slowly and inconspicuously transformed itself into “irrational exuberance”; a boom and bust process10. This set the scene for the next downturn, the perceived need for still more monetary easing, and the generation of still more imbalances. These imbalances are perhaps best treated by looking in more detail at the years just preceding the crisis.

The easing of AME monetary policy in 2001, in response to slowing growth and the stock market crash, was of unprecedented speed and magnitude. Taylor (2007) contends that, in the US, at least it far exceeded the requirements of a Taylor rule (Taylor rule is a monetary-policy rule that stipulates how much the central bank should change the nominal interest rate in response to changes in inflation, output, or other economic conditions). Moreover, rates were also kept down much longer than such a rule would have suggested. This led to a whole host of imbalances, both real and financial, in many AME’s. In the English-speaking countries, household saving rates fell to unprecedented levels and there was a further buildup of household debt. As the price of houses rose, investment in the housing stock also took off. Similar developments were occurring in peripheral Europe as sovereign credit spreads over German Bunds collapsed.

Financial institutions dramatically increased leverage as they increased loans, and the price of financial assets also rose to unprecedented highs. Given that increases in policy rates were being clearly telegraphed in advance, and Sharpe ratios11 raised accordingly, speculation on further increases was strongly encouraged. Finally, via the mechanism of semi fixed exchange rates (to which I will return), the EMEs actively contributed to an explosion of global liquidity and imbalances in their own economies. In short, by 2007 the global economy was an accident waiting to happen and the policy makers all failed to see it coming. How could this have happened?

I would contend that all the relevant policy makers were seduced into inaction by a set of comforting beliefs, all of which we now see were false. Central bankers believed that, if inflation was under control, all was well. As a corollary, in the unlikely case that problems were to emerge, monetary policy could quickly clean up afterwards. Regulators believed that, if single institutions were all healthy, the system as a whole would stay healthy. Nor was the private sector without fault. Bankers and other lenders believed their large profits were due to talent (alpha) rather than risk-taking (beta), and so became ever more exuberant. Borrowers believed house prices and the prices of other financial assets were a one-way bet. Even governments were seduced. Buoyant tax revenues were believed to be “structural” rather than cyclical and were quickly spent.

When the crisis hit, policymakers in the AMEs initially pulled out all the stops. They used a variety of polices to stabilize the situation and in a fundamental sense succeeded. However, each of these policies shared a major shortcoming. Their positive short-run effects were offset by negative longer-term effects. For example, most AMEs allowed their fiscal deficits to expand rapidly in 2009. However, this quickly led to a rapid increase in debt ratios and, in some cases (e.g. peripheral Europe), market pressure to reverse these developments soon developed.

Similarly, measures to support the financial system were needed and were initially successful. However, with the US arguably an exception12, they did not address the underlying problems of an over-extended financial sector and the need for debt write-offs. In effect, most AMEs have chosen the Japanese path rather than the Nordic path to restoring the financial system to good health. Finally, as the weakness of the economy became ever more apparent, the appetite for structural reforms to the real economy also faded.

In short, in the aftermath of the crisis, ultra-easy monetary policy soon became “the only game in town“. Unfortunately, monetary policy shares the shortcoming of all the other policies. Its effectiveness decreases over time, while its negative side effects increase over time. Let me treat these two phenomena in turn. I will distinguish, however, between the undesired side effects in AMEs and those in EMEs. Finally in this section, I will make a few comments about global liquidity. The bottom line is that countries are increasingly interdependent but, sadly, we lack a global governance structure that recognizes this fact.

Central banks have resorted to unprecedented policies in response to the crisis. However, they have sometimes differed in their peculiarities, attesting to the highly experimental nature of these policies13. First, policy rates in most countries were lowered very quickly to almost the Zero Lower Bound. Subsequently, a number of countries even introduced negative rates on reserves held by financial institutions at central banks. Forward guidance, mostly implying policy rates would stay “low for long”, was also used to lower the yields on medium term government securities. In addition, central banks massively increased the size of their balance sheets, generally in an effort to lower longer-term rates, while often altering their composition as well in order to affect credit spreads.

These policies were first directed to restarting financial markets that seized up early in the crisis. With time, however, the focus of AME central banks shifted to emphasizing the need to stimulate aggregate demand14. The policy essentially succeeded in achieving the first objective, in that markets quickly began to operate more normally. Credit and term spreads also fell sharply from previously high levels, with over ten trillion dollars of government bonds carrying a negative interest rate by mid-2016. Some alternative hypotheses about the sustainability of these developments are addressed below.

However, the second objective of stimulating spending has been much harder to achieve, particularly in continental Europe and Japan. Inflation and inflationary expectations have also remained stubbornly below desired levels almost everywhere,15 although the US is somewhat of an exception16. While many central bankers seem to have been surprised by the lack of response of spending to date, both economic history and the history of economic thought should have given ample warning.

In previous downturns after a credit bubble, at least in those cases where the financial sector itself had been weakened, history records that recovery can take a decade or longer17. Moreover, losses to the level of potential are commonly large and permanent. Evidently, to the extent that monetary policy contributed to the financial “boom” and the subsequent “bust”, this conflicts with the conventional belief in the long run neutrality of money.

Turning to this particular crisis, a number of reasons can be suggested for the lack of monetary traction. It clearly has less to do with the signal not getting through (since yields and spreads fell and asset prices rose sharply) than with there being an unusually muted spending response18. Profound uncertainty about the future, not least the future stance of monetary and fiscal policies, might have suppressed “animal spirits”. The experimental nature of current policies, suggesting “panic” to some, might also have worked in the same direction. It is particularly worrisome that corporate investment has been falling sharply, with the proceeds of record bond issues rather being used to buy back stock (or increase dividends) and/or hoarded as cash. I return to the supply-side implications of this below.

Perhaps most important, a lower discount rate works primarily by bringing spending forward from the future to today. In this process, debts are accumulated which constitute claims reducing future spending. As time passes, and the future becomes the present, the weight of these claims grows ever greater. Some part of the weakness of current investment might be due to corporations recognizing the importance of such “headwinds”, particularly the overhang of consumer debt. Why increase productive potential when future demand is likely to be constrained? In short, easy monetary policies are likely to lose their effectiveness over time - and eight years seems rather a long time by anyone’s standards.

These are not just theoretical considerations. The BIS Annual Report of 2014 sounded the alarm when it noted that the level of debt in the AMEs (sum of corporate, household and governments) was then significantly higher than it had been in 2007. Moreover, it has since risen further, to over 260 percent of GDP. This increase has prompted the question “Deleveraging? What deleveraging?”19 This suggests that, by following polices that have actively discouraged deleveraging, we may instead have set ourselves up for an even more serious crisis in the future.

As for the history of economic thought, Keynes himself said in Chapter 13 of the General Theory (1936) that monetary stimulus was likely to be ineffective; “If, however, we are tempted to assert that money is the drink that stimulates the system to activity, we must remind ourselves that there may be several slips between the cup and the lip”. This conclusion marked a sharp change from the policy changes he had recommended in the Treatise on Money (1930). Hayek (1930, p21) went even further in suggesting that monetary easing would actually hold recovery back. “To combat the depression by a forced credit expansion is to attempt to cure the evil by the very means which brought it about”.

There is a rich historical literature on this topic, only one strand of which might be described as “mainstream”. That strand began with Wicksell (1907) who warned that setting the financial rate of interest below the natural rate of interest would culminate in inflation. There has not thus far been any indication of rising inflation in AMEs, though I will suggest a little later that there

are still some grounds for concern. Other strands of thought that are decidedly not mainstream would include: the concerns of Hayek (1933) about real resource misallocations; Minsky’s (1986) suggestion that financial stability breeds instability; Koo’s (2003), observations about balance sheet recessions; and insights from economists at the BIS who have identified imbalances of various kinds that are spread internationally via global capital markets. It seems possible, even likely, that all of these undesired effects of ultra-easy money have been building up under the surface.

There are clearly grounds for believing that monetary policy, both before and since the crisis, has contributed to a reduction in the level of potential or even its growth rate. In fact, both seem to have declined sharply in AMEs in recent years20. As Schumpeter might have put it, without destruction there can be no creation. It is a fact that in many countries, the entry of new firms and the exit of old ones has been on a declining trend. Worse, if easy money actually lowers potential growth, and this induces still more easy money, the possibility of a vicious downward spiral is clear. In the end, rising inflation would bring this process to a halt, but a great deal of real economic damage might have been done in the interim.

As for the mechanisms, unnaturally easy monetary policy before the crisis contributed to the expansion of low productivity industries; in particular, construction, retail and banking21. As well, the interaction of easy financing conditions and management compensation (in some countries, including the US) significantly reduced the incentives to invest22. Since the crisis, these problems have become locked in and others added23. Very easy monetary conditions have encourage banks to evergreen loans to “zombie companies”, which in turn prey on the otherwise healthy and lower their productivity. Furthermore, with banks preoccupied with managing old loans, the availability of credit to new firms (with innovative ideas but no physical collateral) can become particularly constrained. This is a serious problem in Europe.

Another set of concerns has to do with an inadvertent contribution of ultra-easy monetary policy to financial instability. One concern is that it has reduced the viability of financial institutions by severely squeezing term and credit spreads. Insurance companies and pension funds have been complaining about this added threat to their business models and even viability for some time24. This is not surprising since it comes on top of various other problems, not least demographic challenges. What is more surprising is how long it took for banks to complain about the effects of monetary policy, and thinner margins, on their overall profitability. Only quite recently, under the influence of the introduction of a negative policy rate in Europe and Japan, have they added monetary policy to regulatory policy as a source of concern25.

Another financial side effect is that the functioning of financial markets seems to have changed for the worse since the crisis began. With monetary policy (especially that of the Fed) seen to be the crucial factor driving all markets, there has been a marked increase in the correlation of returns within and across asset classes. Moreover, as perceptions have changed as to whether monetary policy would be effective or not, market reactions have bifurcated. When the mood is positive, financing flows (Risk On) to more risky assets, and when the mood is negative the opposite occurs (Risk Off). This focus of RORO investors, essentially on tail risks, seriously reduces the longer-run benefits of diversification and of value investing. A similar set of outcomes will be produced by the recent, massive shift of investors into Exchange Traded Funds (ETF)26. These financial market trends cannot be good for economic growth over time. As well, the likelihood of sharp swings in the prices of financial assets would also seem enhanced.

Against the background of these swings in sentiment, the easy stance of monetary policy might also have contributed to financial market prices getting well ahead of “fundamentals”. As occurred prior to the crisis, “transparency” might also have contributed to this outcome by raising Sharpe ratios and encouraging speculation. As of mid-2016, we observed record high equity prices, record low (even negative) bond yields for “riskless” assets, high-yield spreads back down from February levels, record low costs of cover (e.g.: the Vix27), the return of cov-lite28 and Payment in Kind (PIK) financing, and a general lowering of lending standards. Broadly speaking, the levels of prices in financial markets today look as stretched as they did in 2007 just before the crisis erupted.

Footnotes:

1 “The views expressed are solely those of the author and are not necessarily shared by any institution to which he is currently or has in the past been associated.”

2 For a record of these changes, which have affected all aspects of the conduct of monetary policy, see White (2013).

3 This was the term used by Ken Rogoff in his Adam Smith presentation to NABE in 2011. See Rogoff (2011)

4 The underlying model is that of Wicksell (1936). He drew the distinction between the “natural rate “of interest and the “financial rate” of interest. The former is related to the expected rate of return on investments and the latter is a longer term rate of interest set by the financial system under the influence of the central bank. The latter is observable while the former is not. When the natural rate is below the financial rate, the result will be a decline in the price level and vice versa. In this model, a change in the price level is the only indicator of disequilibrium in the system.

5 As discussed briefly below, a wide variety of economic agents, both private and public, held “false beliefs” that led them to act imprudently. While this paper focusses on central banks, this should not be interpreted as indicating a wish to downplay the important role played by other agents.

6 My initial disagreements with this view were expressed many years ago. See Borio and White (2003), White (2006) and White (2012).

7 It should be noted that fiscal policies in most AMEs erred in the same asymmetric way. Thus, government debt stocks ratcheted up, cycle after cycle, to essentially ” unsustainable” levels in many countries.

8 There was a vigorous debate about such supply side issues in the pre- War period. See Selgin (1997)

9 Careful historical analysis indicates that the Great Depression was essentially unique in their being an association between falling prices (CPI) and a shrinking economy. See Atkeson and Kehoe (2004) and Borio et al (2015).

10 There is now a huge literature documenting earlier crises in which both the real and financial sectors have been affected. Common themes are some early piece of good news that justifies optimism, associated financial innovation, and a significant expansion of credit and debt. In addition to the classic reference, which is Kindelberger and Aliber (2005), also see Reinhart and Rogoff (2009) as well as Schularick and Taylor (2009).

11 Essentially, a measure of risk-adjusted returns. (Evergreen Gavekal footnote).

12 However, in both the US and the UK there was a marked increase in concentration in the banking system. Otherwise put, the “too big to fail” problem got worse. For an explicit recognition that this problem has not yet been adequately dealt with, see Financial Stability Board (2016).

13 For a description of the many differences between the policies of the Fed and the European Central Bank, see Fahr et al (2011).

14 The Federal Reserve was the first and most enthusiastic advocate of such policies. The European Central Bank was much more reluctant, but eventually also subscribed. The Bank of Japan, under Governor Shirakawa, was also reluctant but, under the subsequently appointed Governor Kuroda, things changed dramatically. “Abenomics” subsequently included a massive increase in the size of the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet as one of its three “arrows”.

15 A large part of this is due to weak prices for commodities, energy in particular. However, other measures of inflation and inflationary expectations have also been weak.

16 Core inflation in the US is not much below 2 percent, and most estimates indicate the output gap is now quite small. Nevertheless, both market and survey based measures of inflationary expectations continue to decline.

17 Reinhart and Reinhart (2010)

18 For a fuller description of the various ways in which ultra-easy monetary policy might actually decrease consumption and investment, see White (2012).

19 See Buttiglione et al (2014). For a similar analysis, see McKinsey Global Institute (2015).

20 For a general discussion of these issues, see Bank for international Settlements (2016). Also Borio et al. (2015)

21 See Cecchetti and Kharroubi (2015) for a discussion of the effects on real growth of the expansion of the financial sector.

22 Andrew Smithers has repeatedly and convincingly made the following argument. For a manager whose bonuses are linked to stock market performance, it pays to issue bonds at low rates to either buy equity or increase dividends. Cutting investment frees up more cash to the same end. In a similar vein, Mason (2015) provides empirical support for the argument that “Whereas firms once borrowed to invest and improve their long-term performance, they now borrow to enrich their investors in the short run” He attributes this change to the shareholder revolution of the 1980’s.

23 Borio et al (2015) provide estimates of the magnitude of these effects. They are not trivial, amounting to one quarter of a percentage point off growth (annually) in the upturn and double that in the subsequent downturn.

24 For example, see Hoffman (2013). Also the extensive discussion of these issues in Eurofi (2016). Of particular note, to the extent that low interest rates push up the deficits of corporate pension funds with defined benefits, the corporation must fill the gap. This will be a direct charge on cash flow and profits. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that this will discourage investment.

25 The return on equity for institutions designated as Systemically Important Financial Institutions (SIFIs) has fallen dramatically in recent years. The irony is that, if public sector polices have rendered them unviable while leaving them still “too big to fail”, the taxpayer will once again be on the hook.

26 The insights of those managing active funds has been overwhelmed by these correlations and they have systematically underperformed ETFs. A recent survey indicates that passive funds now account for one third of all fund assets in the US. See Marriage M (2016) and the associated FTfm special report on Exchange Traded Funds which outlines the associated dangers.

27 The Volatility Index (Evergreen Gavekal footnote).

28 Convenant -lite bonds, allowing issuers significant latitude to defer interest payments (Evergreen Gavekal footnote).

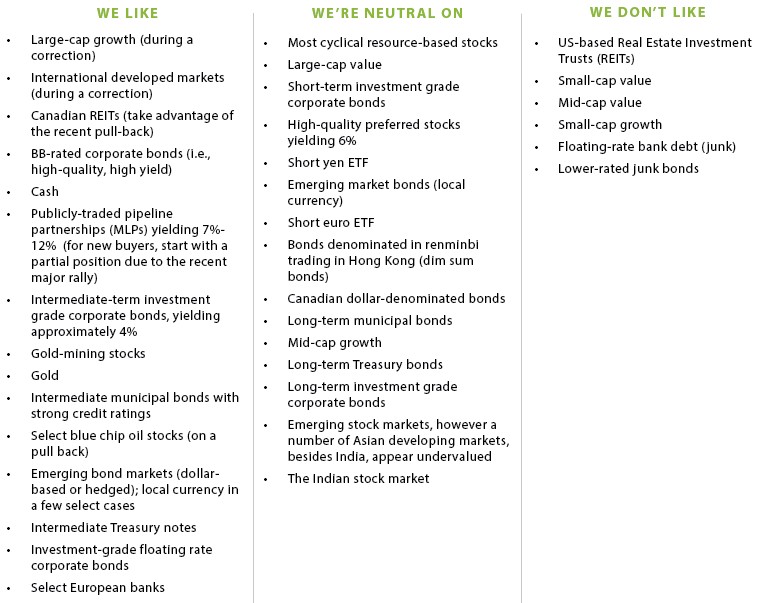

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.