“I will not be buying back stock for the rest of my life. It’s a fool’s game and might make a few investors happy for half an hour. It’s the only decision I regret in six years running CLF.”

– Lourenco Goncalves, Cleveland Cliffs Chairman, President and CEO

“The greatest adventure is what lies ahead. Today and tomorrow are yet to be said. The chances, the changes are all yours to make. The mold of your life is in your hands to break.”

– J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In the investment world, hindsight is always 20/20. The expression has never been truer than in the year 2020, as investors who believed that the longest bull market in history was destined to expand indefinitely were met with an unwelcome surprise towards the end of the first quarter.

But hindsight only considers what has happened in the past. Foresight is a much more elusive ability; one that requires a deep understanding of both the past and present, and the skill to discern future outcomes based on available information. As such, investors who were preparing for a pullback had the ability to deploy capital during the worst of the carnage at the beginning of 2020, while many were panic selling or sitting on the sidelines.

While no man or woman can truly predict the future, it is possible for the skilled investor to anticipate outcomes based on historical patterns and data. Such is the case for this month’s Guest EVA author, Vincent Deluard, who foresaw trouble ahead for Big Tech and US equities back in August.

As you will read below, Vincent has been particularly troubled by the trend in transactions among Big Tech company insiders toward rapidly rising sales and a plunge in purchases (a subject we touched on last week), as well as the fact that corporate buybacks have plummeted this year. The dangers of buybacks, a key theme in Deluard’s piece, is a subject that we’ve frequently warned against in past newsletters (See Bye-Bye Buybacks? and Stock Buybacks are Banned; Let it Be a Trend). In fact, as we highlighted in our February buybacks missive, the buyback bonanza that occurred during the heat of the last bull market was a key driver of inflated share prices:

“To put things in perspective, in 2018 alone companies paid out a combined $1.25 trillion in dividends and buybacks. Per The Financial Times, this is equivalent to the value of all the gold that’s ever been mined… As BofA Merrill Lynch strategist Savita Subramanian has observed: ‘Buybacks work when there’s scarcity value. Now everyone’s doing it.’ To her point, 60% of companies have done repurchases. And they are doing so at a time when the price-to-sales ratio, one of the best metrics for predicting long-term returns, is higher than it was in early 2000 (i.e, the tech bubble apex) and when the Cyclically-Adjusted P/E (CAPE) is around 30.”

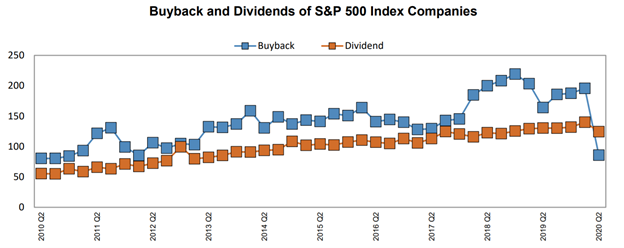

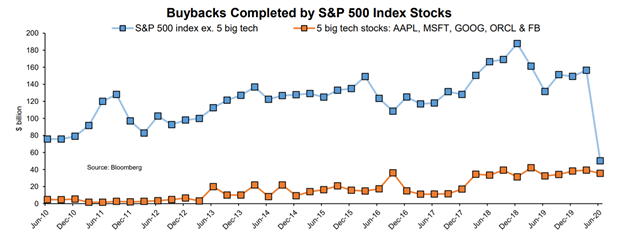

But those banking on buybacks to drive share prices higher moving forward will be disappointed to know that buybacks have plummeted by about 67% ex. Big Tech and by “just” 56% including the five Big Tech buyers. As Vincent point out, this gap has produced a massive supply and demand problem, creating a scenario where there is no long-term source of capital that can make up for a two-third contraction in buybacks.

Another point that Deluard focuses on has been a major pet peeve of ours per numerous past EVAs: that buybacks often enrich senior management and pad earnings. This is particularly pervasive among Big Tech companies, who are currently the main drivers of buybacks:

“Unfortunately for investors, most of Big Tech’s buybacks are not a payment to shareholders, but a convoluted way to pay insiders…The majority of buybacks are actually a hidden way to pay employee: a ‘normal’ company would need to pay an extra 30 to 50% in salary (or even a bit more taking taxes into account), which would reduce free cash-flow. By outsourcing much of their payroll expense to the stock market, Big Tech companies are able to save on taxes and conserve cash.”

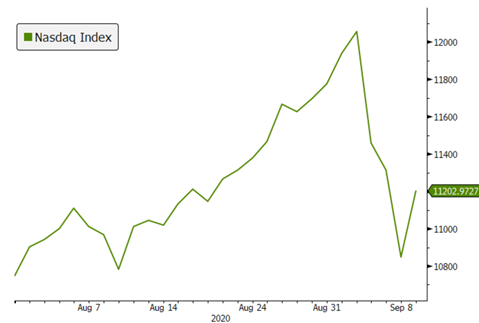

Vincent’s missive is particularly timely because of the sudden carnage in momentum parts of the market. As you can see in the chart below, the Nasdaq dropped off a cliff last week before bouncing back towards the middle of this week.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

With uncertainty swirling around a Presidential election that’s now less than two months away, it’s fair to wonder which direction markets are heading in the not-too-distant future, which is a subject we’ll dive into next week when we present a roundtable discussion among several of Evergreen’s partners about markets and the 2020 US Presidential Election.

“Everyone is getting hilariously rich and you’re not”. Nellie Bowles’s New York Times article on the cryptomania should win the Pulitzer prize for the title alone, with a honorable mention for the pictures of weed-smoking, Burning Man-attending, ramen-eating, ironic T-Shirts-wearing Gen Z’ers co-living in a San Francisco commune aptly called “the crypto castle”.

As Charles Kindleberger observed in Manias, Panics and Crashes: a History of Financial Crises, “there is nothing so disturbing to one’s well-being and judgment as to see a friend get rich.” Indeed, the prudent managers who thought it was crazy to pay 20 times for Apple’s earnings in March amidst a global pandemic must feel intense rage after the company’s value soared by $1.1 trillion in six months.

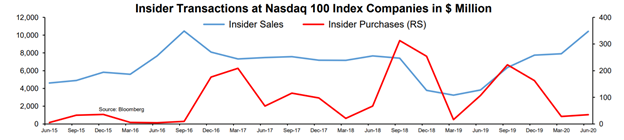

On the other side of the fortune spectrum, insiders at Nasdaq 100 index companies are harvesting a once-in-millennium bonanza: insiders have sold $10.4 billion this quarter, up 171% from last year. At the same time, insider purchases at Nasdaq 100 companies plummeted to $35 million, down 67% from last year.

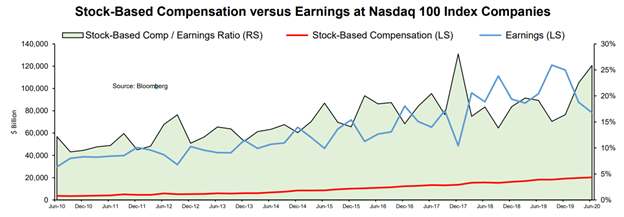

Nasdaq 100 index’s earnings have dropped by 18% from last year but stock-based compensation has increased by 14%. Nasdaq 100 companies paid out $20 billion in stock-based compensation this quarter, which amounts to 26% of earnings, up from 9% in 2010.

The need to offset this massive dilution as well as the resilience of Big Tech’s cash flows leads to yet-another crazy statistic: Apple, Microsoft, Google, Oracle and Facebook repurchased $35.5 billion this past quarter, versus $50 billion for all the other companies in the S&P 500 index.

The supply and demand problem I highlighted in “Imagine a World Without Buybacks” remains. Buybacks have been the largest source of flow into the stock market with ETFs this past decade, and repurchases have plummeted by 76% outside of Big Tech companies. Furthermore, barely half of Big Tech’s buybacks leads to float shrink (the rest should count as disguised salary expense). Retail investors and Robinhood day-traders have replaced buybacks as the marginal buyers of stocks this quarter. Bulls should pray that Dave Portnoy and his 1.7 million followers can come up with $600 bn a year to make up for the durable reduction in buybacks in the post-Covid world.

It is a Party in California!

What a wonderful time to be alive in California! Sure, bars, restaurants, and hairdressers are closed. Wildfires are surrounding San Jose. A permanent dusk has engulfed the Bay Area, adding to a general sense of Armageddon. San Francisco’s smoke and ashes-filled air has become the worst in the world. Kindergarteners (including my 5-year old) are spending 7 hours a day of “school” on Zoom and probably suffering permanent brain damage in the process. Public school teachers must pretend that this charade is in fact “education”, but most would rather catch the virus than struggle to get toddlers to click hyperlinks. There is an entire sub-reddit on “the great California exodus”. Heat waves are causing power shutdowns, most beaches remain closed, and rioters still loot the few stores which have not shut down permanently.

But the Nasdaq index breaks a new record every day, Apple is worth $2.1 trillion (up $1 trillion since March 23), and insiders are cashing in. Corporate insiders sold a whopping $10.4 billion in their companies’ shares this quarter, up 171% from the same period last year. Turning to insider purchases, Nasdaq officers and directors bought just $35 million, down 67% from last year. “Money talks, bullshit walks” should become the new motto of the Bear Republic (I am only half-joking here as I often wonder whether the Pacific Coast states would remain in the union if Trump is re-elected in November).

And why should the Nasdaq-100 hard-working executives and insiders not sell their options when investors are more than happy to take the other side of the trade? The Nasdaq U.S. Insider Sentiment Index, which invests in Nasdaq companies with a high degree of corporate insider buying, has underperformed the Nasdaq 100 index by 50 percentage points this past year. As every farmer knows, there is a time for seeding, and a time for harvesting. Nasdaq insiders are indeed harvesting the crop of a lifetime in the summer of 2020.

Investors should rejoice, too: the 100 companies in the Nasdaq index are worth $14.6 trillion. Earnings have dropped by “just” 18% from last year (which translates into an annualized P/E ratio of 46, but that is probably an irrelevant detail in 2020). At the same time, stock-based compensation has increased by 13.6%, surely a just reward as Nasdaq insiders were forced to take work calls from their Peloton bikes.

Party-poopers may point that the $20 billion paid out as stock-based compensation amounts to a record 26% of earnings, up from 9% in 2010, but I prefer to look at the glass half-full: corporate insiders are allowing the public to keep almost three quarters of profits!

Houston, We Have a Supply & Demand Problem

Smart investors may hate the profligacy and greed of Nasdaq insiders, but it is not like they have many viable alternatives. The market value of the Barclays Negative Yielding Debt Index has soared to $15.5 trillion, 10-year Treasury Inflation Protected Securities guarantee 10% loss in purchasing power, and the Russell 2,000 index trades for a cool 100 times expected earnings.

Investors who feel mistreated by the egregious compensation practices of tech insiders are unlikely to find much solace in “normal” indices. S&P 500 index companies repurchased just $85 billion this past quarter, down 56% from $196 billion in the first quarter. Dividends have also dropped by 11%.

If anything, this chart is misleading because it includes the massive repurchases of five Big Tech stocks: Apple, Microsoft, Google, Oracle and Facebook repurchased $35.5 billion this past quarter, versus $50 billion for all the other companies in the S&P 500 index. If the trend continues – and I see no reason why it should not – the two lines should cross this quarter.

Unfortunately for investors, most of Big Tech’s buybacks are not a payment to shareholders, but a convoluted way to pay insiders. Let me explain.

MBA and CFA students learn the Modigliani-Miller theorem which states that buybacks and dividends are equivalent: the value of a company is determined by the free cash flow it generates. Managers can slice the pizza in whatever shape they want with dividends or buybacks, but they cannot change the size of the pie.

This view may be mathematically correct assuming no taxes and no transactions costs, and, crucially, that buybacks actually reduce companies’ float of stocks. This is usually the case at traditional companies such as Berkshire Hathaway, but buybacks have a completely different role in Silicon Valley.

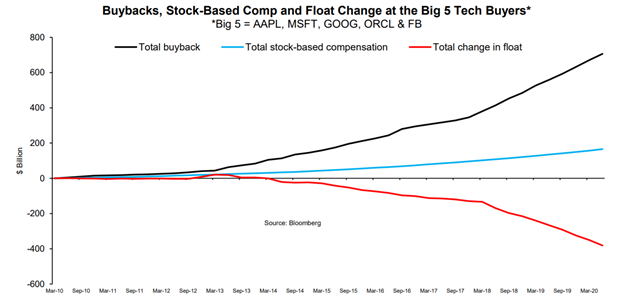

Most Big Tech companies pay 30 to 50% of their salaries in stock options which would lead to very rapid dilution over time if left unchecked. As a result, they need to complete large repurchases in order to keep a stable count of shares. The majority of buybacks are actually a hidden way to pay employee: a “normal” company would need to pay an extra 30 to 50% in salary (or even a bit more taking taxes into account), which would reduce free cash-flow. By outsourcing much of their payroll expense to the stock market, Big Tech companies are able to save on taxes and conserve cash.

As a result, half of Big Tech’s buybacks does not lead to a reduction in the share count. The five Big Tech companies have spent $700 billion in buybacks in the past ten years, but yet their float decreased by just $381 billion. $166 billion went into stock-based compensation and the remaining $153 billion was diluted in some other way (option conversion, cashing out of early investors, convertible debt, etc.)

In other words, the true picture for buybacks is as dire as I forecasted in “Imagine a World Without Buybacks”. Buybacks have plummeted by about 67% ex. Big Tech and by “just” 56% including the five Big Tech buyers. But only 50 cents of every dollar spent on buybacks by these companies leads to float shrink.

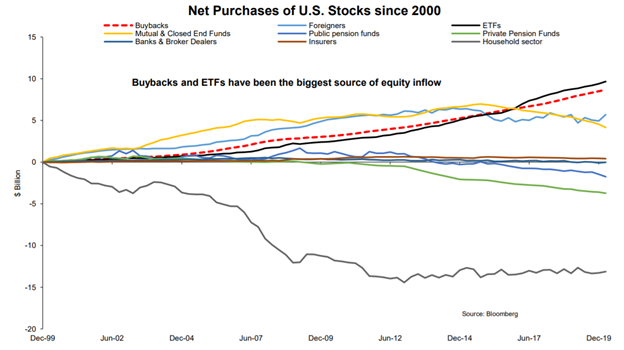

Hence, the stock market suffers from a massive supply and demand problem. Day-traders gambling their stimulus checks and unemployment benefits on Robinhood may have filled the gap left by corporations this past quarter, but over time, there is no source of money which can make up for a two-third contraction in buybacks.

According to the Federal Reserve’s flow of funds, buybacks have been the second largest source of equity demand since 1999: U.S. companies have repurchased $8.7 trillion in the past twenty years, almost matching the $9.7 trillion which went into equity ETFs.

All the other sources of equity demand (pension funds, mutual funds, foreign central banks, sovereign wealth funds, banks, and insurers) have become net sellers in recent years. Unless retail day-traders can inject $600 billion a year in the stock market, U.S. equity indices will experience a major supply and demand problem. Serious investors should stop mocking internet celebrity and #fintwit extraordinaire Dave Portnoy: they better hope that he and his 1.7 million Twitter followers keep buying without thinking too hard about boring old stuff, such as cash flow and valuations.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.