All of us at Evergreen Capital Management want to start this EVA by expressing our deepest sympathy to the people of Japan. The news footage is heartbreaking and a vivid reminder of the frailty of life. While we watch hopefully and root for their speedy recovery, we also acknowledge the impact this disaster has had and will have on global markets.

POINTS TO PONDER

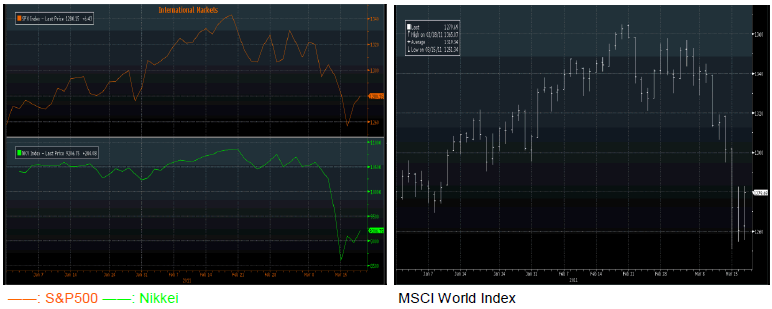

1. The shock waves from Japan’s horrifying earthquake have caused stock markets to plunge worldwide, with the Nikkei Stock Average naturally suffering the most. However, even the seemingly imperturbable US market has cracked somewhat.

2. Nuclear power is once again under a cloud, literally and figuratively, after the serial calamities at the Fukushima Daiichi facilities in Japan. The threat to global energy price stability if large numbers of nuclear power plants are shut down is reflected in the fact that 13.5% of the world’s electricity production is atomic.

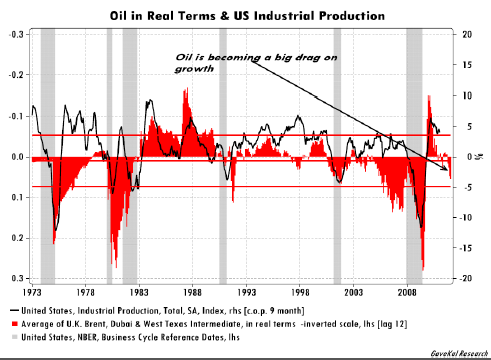

3. Increased upward pressure on oil prices as a result of Japan’s crippled nukes, coupled with ongoing turmoil in the Middle East, is a rising threat to the economic recovery. Over the years, there has been a clear link between oil price spikes and business cycle downturns.

4. After the devastating Kobe earthquake in 1995, the Japanese stock market fell 20%, materially affecting global indexes. However, over the last 20 years, Japan’s weighting in the international benchmark has fallen from 45% to just 10%, reflecting both the magnitude of its former equity bubble and the grinding decline since its collapse.

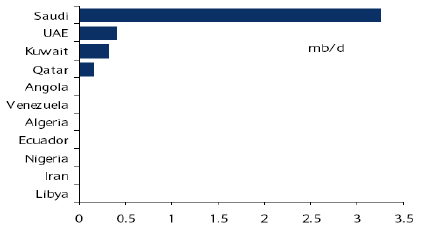

5. The ongoing civil war in Libya, combined with new demands on fossil fuels given the uncertain future of nuclear power, puts even more focus on the rest of OPEC’s ability to produce additional crude oil. While the cartel has ample excess capacity, it is concentrated in just a few countries, especially Saudi Arabia.

EVAluating the Environment

Debacle after debacle. While 20 years is an eternity in the financial markets, it’s a mere blip in the scope of human history. Yet it was only two decades ago that Japan was considered to be the world’s most vibrant economy.

At the time, Japan, Inc., seemed to be gaining market share in nearly all industries, causing America to run massive, and politically explosive, trade deficits against the little island nation. And on nearly a daily basis one “trophy” US property after another—Rockefeller Center and Pebble Beach immediately come to mind—fell under the control of Japanese investors.

To many observers, the land of the rising sun looked like an unstoppable juggernaut, somewhat like an economic version of the military colossus that terrified the world half a century earlier. Yet in hindsight, much of its prosperity was an illusion that was in the process of vaporizing. Once its Mount Fuji-like bubbles in stocks and real estate burst, the deflationary aftershocks would reverberate for years—now exceeding the two-decade mark.

Every time Japan seemed to be getting back on track, a nasty surprise would crop up, whether it was self-induced through a series of poor policy decisions or exogenous like the 2008 collapse by Lehman. Lately, thanks to booming demand for the country’s high-quality consumer products and capital goods from the developing world (notably China), the Japanese economy appeared to finally be achieving “escape velocity” from the Great Recession. Then came the day when the earth—and the sea—wouldn’t stand still.

It’s too early to fully determine all the implications from this heart-wrenching disaster except to say they will be numerous and long-lasting. Perhaps the most significant of all may be the impact on energy dynamics for the planet at large. In particular, the much-vaunted renaissance of the nuclear power industry seems most at risk.

The timing couldn’t be much worse. With inflation raging through the commodity complex, including the energy space, the prospect of halting, or at least materially curtailing, the scheduled boom in new nuclear facilities has the potential to worsen the supply/demand situation. Before the Fukushima Daiichi disaster, more than 400 nuclear power plants were on the drawing boards, with China alone planning to build 10 per year over the next decade. Now, even China is suspending new plant approvals, while Germany is considering shortening the life span of existing facilities.

Unsurprisingly, the anti-nuclear coalition in the US is back on the attack even though the Obama administration continues to voice its support for further development. Most likely, the future of the nuclear industry will continue to be bright in the emerging world, after a hiatus, but that is highly contingent on how the current situation evolves (hopefully, not devolves). In what is now somewhat ironically called the “industrialized” world, political opposition to nuclear power development is almost certain to be fierce.

Suddenly, it’s almost like 1979 all over again…

The Japan Syndrome. Back in the late 1970s, a popular movie about a nuclear plant accident and near-meltdown eerily coincided with the real world calamity at Three Mile Island. The combination proved fatal to any further development of nuclear power on American shores. The radiation released from a crippled Russian nuclear plant, Chernobyl, in 1986 seemed to validate the wisdom of this freeze (despite the fact that it was a crude facility, lacking even a containment shell).

But for 25 years, nuclear power plants operated around the world without any major incidents. The industry seemed to be earning back long-lost credibility, but that all changed this week as the world once again contemplated a China Syndrome scenario.

Presently, the facts on the ground (or in the air) are so muddled that it’s hard to know what is actually happening, but I do believe the simple reality is that it’s going to be much tougher to build nuclear power plants in the “emerged” world than it was a week ago. Yet, as always, there are beneficiaries when there is a paradigm-altering event and our job is to think about who they might be.

Coal, oil, and natural gas are almost certain to see incremental demand. However, due to the higher carbon footprint of the first two, the latter strikes my team and me as the superior choice for the long haul. We believe those companies that occupy the unexciting but lucrative space between the wellhead and end consumers are particularly well positioned.

For one thing, they actually benefit from the present oversupply we have domestically due to the extraordinary success of unconventional drilling for shale gas. As increasing amounts of gas are found, there is increasing need for it to be gathered, shipped, processed, and stored. Currently, there is huge demand for natural gas liquids, such as ethane, that can be used in place of oil-based feedstocks to produce petrochemicals.

Several of our favorite companies are heavily exposed to this part of the energy value chain, notably the master limited

partnerships (MLPs) long endorsed in past EVAs. MLPs, like most equity-type securities, had become extended and

vulnerable to a pullback. Now, as a result of the shakeout seen since Japan’s tragedy, several of our favorites fell

sharply this week, allowing us the chance to lock in some decent prices and attractive yields. While they have bounced

since then, if the swoon resumes we will become much more aggressive buyers (I realize that’s about as surprising as

another losing season by the Seattle Mariners!).

Naturally, more traditional energy plays, like blue chip oil stocks, also have become increasingly appealing, though shares have stayed close to recent highs. The bottom line is that we expect energy prices to experience higher highs and higher lows as a result of this series of devastations.

And this might even influence the Fed’s current highly contentious monetary policy, which is looking even more ill-advised given the events in Japan. But, then again, who am I to criticize an institution that has helped orchestrate the events described below?

Still crazy, after all these bubbles? Over a year ago, I did a three-part series on the fallacies of the efficient market

theory. Many may have felt the topic was relevant only to academics and investment professionals, but I strenuously

beg to differ; I’m convinced it was central to the serial debacles we’ve suffered since 2000.

For a quick refresher, the efficient market theory holds that the pricing mechanism of financial markets always and everywhere

accurately reflects the sum of available information. Consequently, the theory is that stocks, as well as other

critical assets such as real estate and bonds, are appropriately valued at all times.

Certainly, the Fed has believed in the efficiency of markets or at least acted as if it does. The first costly example of this was back in the 1990s when, after a feeble attempt by former Fed head Alan Greenspan to warn of irrational exuberance, our central bank essentially drank the Kool-Aid. Those at the Fed became believers in, and enablers of, the most dangerous stock market bubble since the late 1920s (at least outside of the aforementioned Japanese mania of the late 1980s).

It became the Fed’s party line that millions of starry-eyed tech investors couldn’t be wrong. It really was a new internet-driven era of limitless prosperity. Ergo, even P/Es in excess of 100 on large cap tech stocks like Microsoft, Cisco, and Qualcomm were perfectly rational because, after all, markets always knew best, right?

As a result, the Fed turned a blind eye as the speculative bubble in tech stocks inflated to monumental proportions. It whiffed the chance to raise margin requirements and fanned the speculative fires by letting money growth run wild due to Y2K concerns.

Once the tech wreck occurred, destroying trillions of dollars of capital, the Fed panicked, fearing a replay of the deflation and stagnation that had already plagued Japan for over a decade. To forestall this perceived risk, it cut interest rates down to the then unheard of level of 1%. The worst part was that the Fed kept rates there even as it became clear the economy was in the midst of a vigorous recovery in 2003.

And this leads us to the second immense bubble, this one of the real estate variety. Super cheap money combined with exotic new home financing schemes―such as adjustable-rate mortgages (which former Fed Chairman Greenspan actually had the chutzpah to publicly endorse), no doc mortgages, no down loans, and a host of other incredibly reckless lending products―put even more rocket fuel into the tank of the rapidly building property boom. (Longtime readers will recall that I wrote so frequently and critically of this situation that I know some were wondering if I was a short-seller masquerading as a long-only investment adviser.)

Once again, the Fed was in its preferred “see no bubble, hear no bubble” mode. Even worse than suppressing interest rates too low and too long, it (and other government bodies) took no action to enforce prudent lending standards. It once again evinced supreme faith in the financial markets to adequately price risk and parcel it out to sophisticated buyers who could adequately assess the downside.

And also once again, this turned out to be a massive miscalculation. It is bitter irony indeed that by trying to avoid Japan’s experience, the Fed actually recreated it, enabling and/or producing twin bubbles in stocks and real estate. Then when these blew apart, it responded with the same policies of super low interest rates and money printing, only with even more speed and force.

Now the Fed is at the point where its emergency remedies may be doing more harm than good.

The Fed’s latest conundrum. Because the destruction wrought by the bursting of the housing and credit bubbles in

2008 is so fresh, there is no need to rehash all the horrors caused by their implosion. But I do feel it’s very important

for investors to analyze the implications of the Fed’s current efforts.

In the March 4th EVA, I reviewed how the Fed’s latest attempt to deal with the sordid realities of a post-bubble world has led it to inflate another one, this time mostly involving commodities. Some of my team members felt the connection between the Fed’s current printing-money stance and high commodity prices wasn’t clear enough. Therefore, I’ll try to rectify that while considering the impact from Japan’s misfortune.

To be as direct as I can, the Fed has essentially created almost $2 trillion of new money that it’s used to buy government securities. This is somewhat like a corporation issuing massive amounts of its own stock, an activity known as dilution. In effect, the Fed has been heavily diluting the dollar.

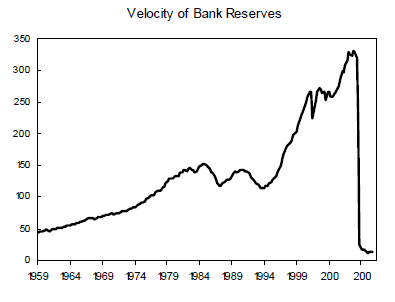

In the early stages of the crisis, this made sense because the turnover of the money supply (known as velocity) had crashed. Money was simply stuck as the banking system basically froze. This meant the Fed needed to flood the system with liquidity to avoid a repeat of the early 1930s. Given the lack of monetary velocity, there were no concerns this would lead to inflation.

Today, however, it’s a different scenario. While money turnover remains muted, it is no longer falling. Thus, a massive amount of created money doesn’t merely sit idle in banks as it did two years ago. Since last summer, this sea of liquidity has increasingly been flowing into hard assets, inflating the value of semi-finite resources like gold, copper, and even rubber.

Because unemployment remains extremely high around the world, particularly in developed countries, upward wage pressures are non-existent. Also, due to the fact that advanced economies are largely service based, labor costs are much more important than commodity prices. As a result, despite massive money creation, the overall CPI stays subdued.

Yet, all of that manufactured money has to go somewhere and, as described above, one of the preferred destinations

has been into commodity plays. The Fed has had a tendency to underestimate financial “innovations,” like sub-prime

debt and credit default swaps, often leading it to miscalibrate monetary policy. Right now, it may be overlooking another

new trend, in this case the proliferation of commodity-based ETFs.

These now allow a wide range of investors, both retail and institutional, to buy and hold commodities. The days of a

limited number of speculators competing against a select group of commercial users (think food producers like General

Mills trying to hedge against rising corn prices) are over. They are now dwarfed by hundreds of billions of dollars from,

in many cases, investors like California’s giant pension fund that see commodities as an important and permanent part

of their portfolios—at least when they are going up.

Therefore, when everyone knows the Fed is printing money, this new breed of “buy and hoard” investors charges into the relatively illiquid commodity world, driving prices up to levels well beyond where they would go in the past. This then sets off a most unpleasant chain reaction.

When stimulus fails. As commodities soar, consumer confidence drops because disposable income is increasingly expended to buy gas and food, leaving less money to buy things like cars and furniture. For example, as inflation expectations have risen lately, one-third of consumers in a recent RBC survey said they had materially cut discretionary spending. This has caused some experts to sharply lower first-quarter GDP projections.