“If a far-sighted capitalist was present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville Wright down.”

-WARREN BUFFETT

In last week’s edition of our Guest EVA, we ran the first half of a condensed version of Grant Williams’ exceedingly popular Things That Make You Go Hmmm. No one ever accused Grant of short-changing his readers as his weekly missives often run to 30 pages or more. But they are chock full of some of the best non-consensus insights, spiced with biting humor, this side of another Grant (as in Jim Grant).

Grant (that would be Williams) appropriately titled his piece, “Never Say Never Again”. In it, he pointed out the past folly of absolute statements about certain events never happening. A classic example he cited was of America’s most famous economist who, back in 1929, boldly stated stock prices would never decline from their “permanently higher plateau”. He then aptly drew the comparison with Fed chief Janet Yellen’s recent pronouncement that we would never see another financial crisis in “our lifetimes”.

Every time I hear or read those types of extreme comments, I can’t help but shake my head and think that such words are destined to come back to haunt their author. Mere months ago, there were learned voices waxing that the oil prices were subject to a permanent ceiling at $50. As you may have noticed, that “permanent ceiling” has already been shattered to the upside.

Now, let me be the first to concede that despite making a lot of very respectable calls on the economy, the bond market, the dollar, oil prices, et al, in recent years, I have GREATLY underestimated the duration of this bull market. However, I was never so brazen as to say it could never keep going up. In fact, I have often conceded that the era we are in now has no past precedent. Consequently, as I’ve frequently written, all predictions should come with a warning label on them, including mine.

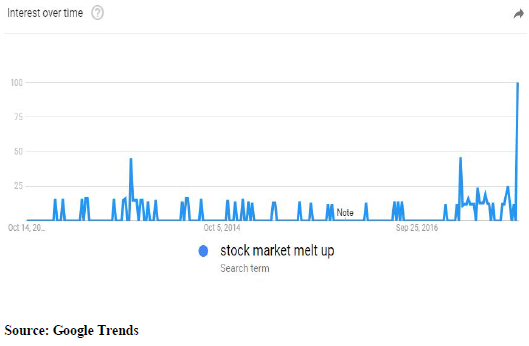

(On that score, I have been anticipating a serious market correction during the fall as so often happens this time of the year. That could still happen but it is looking less likely. As a result, I’ve been reluctantly migrating into the camp that we could see the market surge at year-end, the heavily-hyped melt-up scenario. What is causing me second thoughts about my second thoughts is that almost everyone seems to be expecting it to happen. However, if it does, I do believe it would be catastrophic for most investors as it would suck in the least sophisticated and least able to afford big losses at insane prices.)

The latest instance of a recklessly absolute statement caught my eye even before Grant picked up on it. To avoid totally stealing his thunder—and thunder is what he brings on a regular basis against the absurdity in so many market corners these days—I’ll only say that airlines may be the most capital intensive and cyclical industry in human history. As Grant notes, it wasn’t long ago that it had posted a cumulative net loss going all the way back to its infancy (hence, Mr. Buffett’s Kitty Hawk comment). It is also notoriously exposed to high oil prices. Accordingly, if Evergreen’s view that by 2020 crude may be back around $100, the airlines will—once again—face some gale-force headwinds.

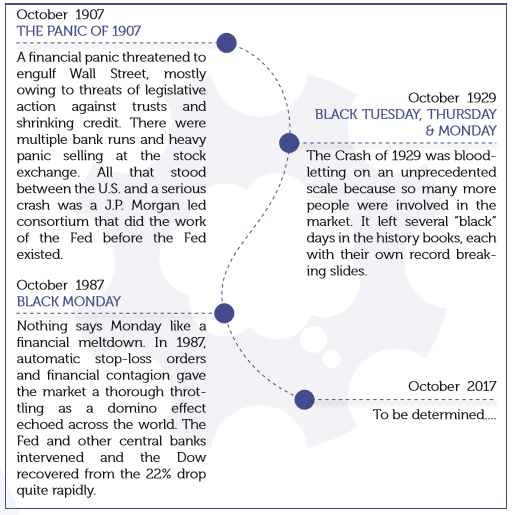

Even if you don’t have much interest in, or affinity for, airline stocks, you still may be intrigued by the cavalier attitude presently prevailing toward an industry that has traditionally been a graveyard for investor wealth. It’s just another indication of the prevailing complacency typified by the consensus conviction that we’ll never go through another October, 1987 type crash or—even more improbable—a replay of the 2008 debacle…at least not in their lifetimes.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

NEVER SAY NEVER AGAIN (PART II)

By Grant Williams

(Continued from last week’s EVA…)

Worryingly, the academic/central bank hubris has finally crossed over to the private sector:

(Dallas Morning News): “American Airlines CEO Doug Parker says the once-volatile industry has changed so radically that his company will never lose money again.

Even in a bad year, Parker says, the world’s biggest airline should earn about $3 billion in profit before taxes...

From 1978 through 2013, American’s cumulative profit was $1 billion. By the end of this year, Parker says, the Fort Worth-based airline will have earned $19.2 billion in pretax income in the last four years.

Airlines have benefited in that span from lower fuel prices, higher revenue from fees, and less competition because of mergers. American, Delta, United and Southwest control more than 80 percent of the U.S. air-travel market.

‘I don’t think we’re ever going to lose money again,’ Parker said. 'We have an industry that’s going to be profitable in good and bad times.' ”

Why do people say such things?

…

But don’t take my word for it – here’s Forbes’ assessment of Parker’s comments:

(Forbes): “True, American earned just over $1 billion in first-half profits this year. And all North American carriers combined earned $15.4 billion in the first six months of 2017. But carriers this year are benefiting from fuel prices that are less than half what they were, on average, in 2013. Back then, the industry paid an average of $3.07 a gallon. Last year, it paid just $1.46. And so far this year, the average is about the same, although prices have recently spiked into the $1.70-$1.95 range in the wake of Hurricane Harvey, which disrupted oil production in the Gulf of Mexico and refining and pipeline operations in southeast Texas in late August.

In fact, last year, when American by itself earned $2.7 billion, U.S. airlines combined to report 'just' $13.5 billion in net profits, down $11.3 billion from the $24.8 billion they earned in 2015. They experienced that staggering 45.6% decline in profits in 2016 despite the fact that they paid 36 cents, or 20%, less per gallon for jet fuel than in 2015.”

Does that sound to you like an industry that’s so stable it could never possibly lose money again?

The deeper you dig, the more outlandish Parker’s claims become:

(Forbes): “Until 2014 the U.S. airline industry was still showing a net-negative number in the 'profits' category.

For the first almost 85 years of their existence U.S. airlines were cumulatively still in the red. And even if you include the $55.7 billion the industry has earned in the previous four years, their cumulative historical return on invested capital is staggeringly negative.

And that’s not even counting the hundreds of billions of invested dollars written off in the dozens of bankruptcies that litter the industry’s history.”

Indeed, the list of potential pitfalls that airlines have to navigate is, to quote the late Nick ‘Goose’ Bradshaw (I bet you never knew that was his full name!!), long but distinguished.

Leaving aside those volatile oil prices, the airline industry’s high fixed costs leave them vulnerable to union action (not a good place to be as the squeezing of the middle class continues apace) while a recession habitually plays merry hell with airlines’ profitability (need I remind you that we are nearing the second-longest expansion in U.S. history?).

Let’s see, what else? Did I mention the fact that airlines tend to get stuck with too many of the wrong type of plane periodically due to changing customer tastes?

By ‘periodically’ I mean ‘regularly.’ It happened in the 1940s, 1950s, late-1960s, 1970s, early-1980s and again in the 2000s.

Meanwhile, the international markets (where the big U.S. carriers currently make the lion’s share of their profits) are becoming not only more competitive, but far more difficult to navigate profitably as this piece of news (which hit the wire in the U.K. a mere four days after Parker’s press conference) demonstrates perfectly:

(BBC News): “Monarch Airlines has ceased trading and all its future flights and holidays have been cancelled, affecting hundreds of thousands of customers.

About 860,000 people have lost bookings and more than 30 planes will be sent by the Civil Aviation Authority to return 110,000 holidaymakers who are overseas.

Monarch employs about 2,100 people and reported a £291m loss last year.

Terror attacks in Tunisia and Egypt, increased competition, and the weak pound have been blamed for its demise.”

Now, the U.K.’s Monarch Airlines is no American Airlines competitor. It’s a low-budget carrier which services largely fringe European tourism destinations (Turkey, Tunisia and Egypt were three of the carrier’s big hubs) BUT... this was still the biggest airline bankruptcy in British aviation history.

…

The UK Daily Telegraph’s reporting of the announcement highlighted just how tricky the airline business can be:

(UK Daily Telegraph): “The fall comes as the airline industry struggles with too many available seats on flights. While some airlines have cooled the level of seat growth they had planned since the Brexit referendum last year, the low oil price has helped airlines keep a higher number of seats in the air than they might otherwise be able to do.

A vicious price war has also seen carriers fighting to cut fares. EasyJet said flights to beach destinations from the UK in particular had seen prices fall sharply...

In spite of pressures in the airline industry, with the collapse of Monarch Airlines this week and a raft of cancellations announced by Ryanair, easyJet said it would increase its seat capacity by 6pc in the next 12 months even though it expected downward pressure on ticket prices to persist.”

Airlines are notoriously fragile and incredibly sensitive to three inherently unstable factors; currency fluctuations, oil prices and economic recessions.

Leaving 2007-2009 aside, a report by Dawna L. Rhoades entitled: Crisis in a Fragile Industry: Airlines Struggle to Survive in an Uncertain Future, looked at the airline industry amidst the shallow and short-lived recession of 2000-2001 in the United States.

What she found ought to make Doug Parker wince:

(Dawna L. Rhoades): “In early 2001, the U.S. airline industry was already feeling the effects of one of its great historical enemies—economic recession—and expected to lose $3 billion.

Economic recession exposes overcapacity in the market— too many seats and not enough passengers. As demand falls, prices decline as carriers scramble to fill seats and retain market share. This tends to place further cost pressure on carriers struggling from declining yields, the difference between cost per available seat mile and revenue per available seat mile.

The industry then experiences a series of bankruptcies and consolidations before the cycle begins again.

The last U.S. recession in 1990–1991 combined with another perennial enemy of aviation, war (in this case, the Gulf War of the early 1990s), to produce industry losses of $10 billion. These losses would pale in comparison to those of the current [2000-2001] crisis.

In fact, the first decade of the twenty-first century has been the 'Perfect Storm' for the global airline industry that has experienced a confluence of four distinct factors.

Two of these factors have a long history of creating problems for the industry—economic recession and war. The other two factors were new—the 9/11 terrorist attacks and potentially severe contagious diseases such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and bird flu.

Together these factors created a crisis that resulted in worldwide airline losses greater than all the profits made in the industry since the 1903 flight at Kitty Hawk by the Wright Brothers.”

As recently as 2012, IATA head, Tony Tyler’s ‘State of the Industry’ speech in Beijing focused on the difficulties inherent in the airline industry:

(Tony Tyler): “...the state of our industry is fragile.

Over the last decade airline revenues totaled $4.6 trillion. We were among the world’s fastest growing industries. But our best annual profit margin of the century so far was 2.9%. And the overall result has been a net loss of $16 billion.

2012 is another challenging year. We expect revenues of $631 billion but a profit of just $3.0 billion. That’s a 0.5% net margin.

And that projection comes with some serious downside risks...

...

The biggest and most immediate risk, however, is the crisis in the Eurozone. If it evolves into a banking crisis we could face a continent-wide recession, dragging the rest of the world and our profits down.

The industry’s profitability is balancing on a knife edge. If the bottom line worsens by even the equivalent of just 1% of revenue, our $3 billion profit very quickly becomes a $3 billion loss.

Furthermore, competition to deliver value is as tough as ever. A web search priced economy fares for the 22,000 kilometer round-trip from New York to Beijing in the range of $1,500. That’s seven cents per kilometer. By comparison, a New York taxi ride costs $1.25 per kilometer, or 31 cents with four passengers on board...

Aviation is a complex global business. It’s not an easy one to manage. Profits, when we have them at all, are razor-thin. And keeping revenues ahead of costs is a never-ending challenge.”

That’s some place from which to make claims of eternal profitability, Doug.

Unfortunately, we can’t short remarks like Bernanke’s or Yellen’s, nor can we take the other side of pronouncements like those made by Fisher or Parker, but we can pay attention and note that these comments (as well as the kind of sentiment apparent in the gauge, below) tend to occur immediately before major moves in the opposite direction.

Peter Atwater of Financial Insyghts does incredible work in assessing when mood and sentiment may have reached extremes and all his warning lights are flashing bright red.

…

For the time being, every asset class in the investing universe seems to have reached another permanently high plateau. I think we all know, deep down, that such an idea is not only ludicrous, but the very fact that sentiment has reached the levels spotted by my good friend Jonathan Tepper should have every one of you checking your portfolio.

And while none of this is news to readers of Things That Make You Go Hmmm... [or the Evergreen Virtual Advisor, for that matter], the fact that it is finally making it into investment bank research is yet another sign that things could well be about to blow:

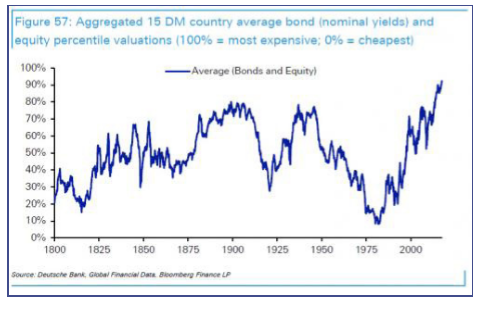

(Deutsche Bank): “Figure 57 updates our analysis looking at an equal weighted index of 15 DM government bond and 15 DM equity markets back to 1800. For bonds we simply look at where nominal yields are relative to history and arrange the data in percentiles.

So a 100% reading would mean a bond market was at its lowest yield ever and 0% the highest it had ever been. For equities valuations are more challenging to calculate, especially back as far as we want to go.

In the 2015 study (‘Scaling the Peaks’) we set out our current methodology but in short we create a long-term proxy for P/E ratios by looking at P/ Nominal GDP and then look at the results relative to the long-term trend and again order in percentiles.

As can be seen, at an aggregate level, an equally weighted bond/equity portfolio has never been more expensive... it’s easier to be black and white in terms of bonds long-term value. In short there isn’t any relative to history...

For equities, current valuations are certainly stretched relative to nominal GDP through history. We have been more expensive but we are approaching the peaks of 2000 and 2007 and are in line with the most stretched valuations from the 1930s on this metric and higher than the 1929 crash point.

Given how weak nominal and real GDP has been post GFC, and how much of a downward trend both have been for several decades now, this shouldn’t be a surprise...

... we’d repeat that history suggests all this is mean reverting over the medium to long term. If we look at more detail on the US which has the most developed history of equity data, including the longest series of earnings data through history we can see the longer term issues with equity market valuations.

Indeed the US CAPE ratio has only been higher before the 2000 equity bubble bursting and was only slightly higher ahead of 1929 crash.”

Deutsche Bank’s conclusion is just about as forthright as it’s possible for an investment bank to be:

“While there are no obvious triggers for historically high global asset valuations to correct, while they remain this high there is always a risk of a sudden correction that could be destabilizing to a financial system and global economy that seems to require such elevated asset prices.”

The fact that the misplaced confidence and hubris of central bankers has now reached the private sector means just one thing in my mind; even though we made it through September unscathed, with the 30th anniversary of Black Monday only weeks away and the environment eerily similar to 1987, it’s time to get serious about the likelihood of yet another in along line of October surprises.

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.