“On what principle is it, that when we see nothing but improvement behind us, we are to expect nothing but deterioration before us?”

-MATT RIDLEY, author of The Rational Optimist

Even a close follower of economic and market dynamics might wonder what in the world robots and Fed policies have to do with each other. According to this month’s guest EVA, courtesy of our partners at GaveKal Research, the surprising answer is, quite a bit.

While there are likely many reasons the Fed’s multi-trillion “large-scale asset purchases” (LSAPs) have been ineffective at spurring the economy to its usual trotting speed of 3% growth or, similarly, accelerating job gains to their normal pace, the “mainstreaming” of robots is a rising factor. This is not to minimize other intractable issues such as skills degradation due to long-term unemployment but, regardless of the cause, these dynamics are highly resistant to even the Fed’s magical money manufacturing machine.

As my close friend, Louis Gave, discusses in the first section of this issue, the rate of robot adoption appears to be at an inflection point. Industrial robots have become smarter, cheaper, and easier to program, as well as reprogram. Moreover, they can now perform multiple and increasingly complex tasks. This means that companies, even in China, are deploying these 24/7 “workers.” In the developed world, they have the immense attraction of not going on strike or requiring expensive benefit packages.

Furthermore, although Louis doesn’t specifically mention it in this piece, due to the fact that the Fed has collapsed the cost of money, it has made the returns from borrowing (or using zero-return cash) in order to fund capital expenditures to further automate production highly attractive. Ergo, this is another unfortunate unintended consequence of QEs ad infinitum (or, in the mind of this author, ad nauseam).

The upshot of this automation acceleration is that there may be millions of Americans who, most sadly, are becoming relegated to permanently unemployed status. As a result, the Fed’s $3 trillion (and counting) solution to chronic joblessness may be ineffective or even counterproductive. By trying to force the unemployment rate down to a level below the “new normal, ” and producing another asset bubble in the process, the Fed is playing a very dangerous game.

On a much more uplifting note, Louis’ colleague, Cathy Holcombe, just wrote a companion piece on this theme, highlighting how countries with poor demographics are increasing their reliance on robots to cope with an aging and declining workforce. Also, as Louis notes, there has always been upheaval when new production efficiencies are introduced. In the long run, though, society benefits as consumers are required to work significantly fewer hours to afford the same goods. Yet, the transition is never easy, particularly for those disadvantaged by the breakthroughs.

Next up is GaveKal’s resident Fed watcher, Will Denyer. He questions the recent bouncy string of PMI (Purchasing Managers Index) surveys that are at odds with generally weak data. (A side note is that, notwithstanding this month’s employment release, before the Fed launched QE3, the US economy was creating an average of 200,000 jobs per month; almost one trillion dollars later, the monthly rate is just 150,000—talk about not much bang for the buck, or trillion bucks!)

The accepted wisdom is that as soon as the Fed backs off of its LSAPs, the bond market will be nuked. Yet, as Will points out, it is hatching a scheme to force the banking system to step into its shoes. This is an important concept I haven’t seen from other sources. It’s just a proposal now but it’s not implausible given the trend for US regulators to treat firms like JP Morgan and B of A as governmental piggy banks (I guess this is what these banks get for acting so piggy during the housing bubble, but it is now bordering on the confiscatory).

Additionally, there is a one-pager from one of my favorite Imax-like thinkers (i.e., ultra-big picture), Charles Gave. He explains why the stock market may have become a lagging, rather than leading, indicator thanks to the Fed’s “Great Levitation.”

Finally, I wanted to provide a brief update on Capitan William Swenson, the Seattle native who recently won the Medal of Honor (if you missed the EVA on him, please click here). Due to the generosity of a number of EVA readers, we have accumulated over $15,000 to recognize his exceptional service to our country and his fellow soldiers.

Captain Swenson emailed me earlier this week to thank me for our efforts on his behalf and his comments were revealing. He would like to use these funds to set up a foundation to help other veterans through a wilderness program. My reply to him was that there are no strings attached and that he should feel free to use the money in any way he sees fit. It’s been my assumption that after two years of what he refers to as his “forced early retirement” from the military, he likely has an acute personal need for financial assistance. However, it is characteristic of Captain Swenson, based on the actions that won him the Medal of Honor, that he would seek to use these funds to assist his fellow servicemen and women.

Thanks very much to those of you who aided us in this attempt to express our gratitude to one of our nation’s legitimate heroes.

VIVA LA ROBOLUTION

Louis Gave

While inspecting shiny new assembly line machinery in the early 1950s Henry Ford II is famously said to have asked Walter Reuther, “How will you get union dues from them?” only for the United Automobile Workers chief to reply, “How will you get them to buy your cars?” The tension between labor and automation systems is nothing new. Back in the early industrial revolution, the artisan Luddites raged against mass mechanization of the textile industry and even at the turn of the 20th century a major concern in the likes of Britain, France, the US, and Australia was the labor market consequences from the rapid industrialization of agriculture.

Massive gains in productivity, itself a direct result of the mechanization of agriculture (along with improvements in seeds, fertilizers, overall farming knowledge, etc) had many beneficial effects, not least of which was the ability to work a lot fewer hours to feed one’s family. In 1895, twelve oranges cost two hours of work in the US. By 1997, the cost of these same oranges was down to six minutes. Similarly a bicycle bought from the now defunct US retailer Montgomery Ward cost the equivalent of 260 hours of work in 1895, but had fallen to just 7.2 hours a century later.

If nothing else, this illustrates the profoundly deflationary nature of capitalism. Fundamentally, market capitalism is about making more with less. And if possible, much more with much less. Which brings us back to the suggestions made last week in The Yellen Thud.

• The unique thing about the current US economic cycle is that longterm unemployment remains stubbornly high, even as short-term unemployment has fallen to normal levels.

• This may be because the “long-term” unemployed are actually now unemployable—i.e., they have dropped out of the effective labor force.

• This in turn could explain why wages are rising even as official unemployment remains high: the market for people with useful skills is getting tighter, but a big chunk of the population lacks those skills and so becomes unemployable.

If these ideas are right, then the current high unemployment rate is a structural, not a cyclical phenomenon. We can also see an explanation for why corporate margins have stayed high despite a lackluster economic environment. The ultimate cause is automation: companies’ everincreasing ability to replace low-value added workers with machinery or software means that corporate margins and wages for skilled workers stay strong, even as a whole segment of the Western-world workforce finds it more challenging to obtain gainful employment at all.

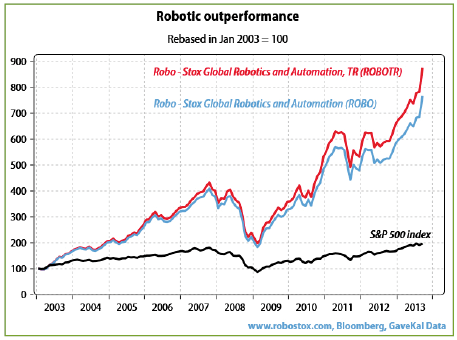

The growing importance of robotics is a long-standing GaveKal theme, even if it remains a somewhat fuzzy concept, bringing together change effects from machines, processes and industries. Nonetheless, over the past few years, we have endeavored to build our own “robotics index (see Robots at a Tipping Point or Robots Ignore the Business Cycle) only to see others do a more thorough job (see www.robostox.com or Bloomberg ticker ROBO and ROBOTR). Now, of course, any index built retroactively is going to benefit from a serious survivorship bias, but even with that in mind, the performance of robotics in the past five years has been nothing short of impressive (see chart below):

This performance is all the more noteworthy since, over the past five years, global capital spending has been mostly lackluster. In turn, this begs the question of whether robotics is approaching the ‘demand take-off’ point that typifies the structural growth trend of successful technologies.

Indeed, any new technology typically goes through an initial phase where price points are so high that only a few ‘early adopters’ can afford the new revolutionary product. This was the case for autos, air conditioning units, televisions, cell phones and personal computers… And until now, it has been the case for most high-end manufacturing robots. However, the question investors should ask is whether we have now reached a tipping point? And it’s not just about the US$10,000 robots that electronics assembly giant Foxconn claims it will be producing by next year. Nor is it Bill Gates’ recent forecast that new generation robots may become as ubiquitous and have as transformative an effect on our economies and our lifestyles as the personal computer. Instead, it’s about everything we see about us: from Paris’ driver-less metro trains, to Panasonic’s fully automated plasma screen plants in Osaka. Everywhere we care to look it is hard to avoid the conclusion that an increasing number of jobs are being replaced by machines and smart software. Even the rabbi’s matchmaking duties are now being replaced by Match.com’s algorithms (or, in the rabbi’s case, www.jdate.com).

But as with the PC revolution of the 1990s, it’s not all about price. Indeed, the first generation of industrial robots did relatively simple yet repetitive tasks on production lines where labor was expensive and fault-tolerance was low. Such machines brought precision to Japanese car factories and Taiwanese wafer fabrication plants, allowing lean production with minimum wastage. What they did not do was fundamentally change the nature of industrial automation which over the last 200 years has grown increasingly capital intensive and sophisticated. Until now, that is. Indeed, to even the most casual of observers, the obvious conclusion has to be that robots are becoming sufficiently smart and affordable to change the way manual tasks are undertaken in both developed and developing economies. New generation robots can be programmed to undertake complex tasks that allow easy replacement of physical labor; and can then be reprogrammed to do different tasks.

In a move reminiscent of General Motor’s purchase of the Los Angeles, San Diego and Baltimore tramways in the 1950s, Amazon spent US$775mn in 2012 on Kiva Systems, a supply chain robot maker. Clearly, Amazon’s goal was to not only move one step above the competition in terms of supply-chain efficiency, but also ensure that the competition stayed one step behind. Or take Foxconn, with over 1mn employees, the company is on record as wanting to effectively replace 300,000 workers with robots over the next three years. Already, the company’s highly secretive new Chongqing plant in China is reportedly experimenting with robot-run production lines.

Very soon, large-scale robotic adoption and production by firms such as Amazon or Foxconn will fundamentally change the competitive dynamics of their entire industries. But just as IBM and Cisco dominated the first phase of the computing and internet cycle, the early winners of the robotic revolution will likely be the makers of core infrastructure. Which probably explains why the performance of the robotics index above is so strong, even in the face of fairly mediocre global capital spending.

DEMOGRAPHICS: LET THE RACE BEGIN

Cathy Holcombe

In Race Against The Machine, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee speculate that many of the jobs cut in the Great Recession may never come back, as employers take the opportunity to switch to automated services. The authors warn of “a growing mismatch between rapidly advancing digital technologies and slow-changing humans.” The challenge for workers—the “Race” in the title of the book—is to develop new skills or be left behind by the digital age.

Yet there may be a silver lining in the Great Recession’s hastening of the digital age. Consider that in 1950 only 8.1% of the US population was 65 years of age or older, and it took 60 years for the elder-share to expand just 5pp, to 12.9% in 2010. Now the old are moving much more quickly: by 2015, 14.4% of the US population will be over 65, rising to 16.3% by 2020, according to widely accepted UN estimates. This demographic shift creates a heavier load for the working-age population—one that robots may help alleviate.

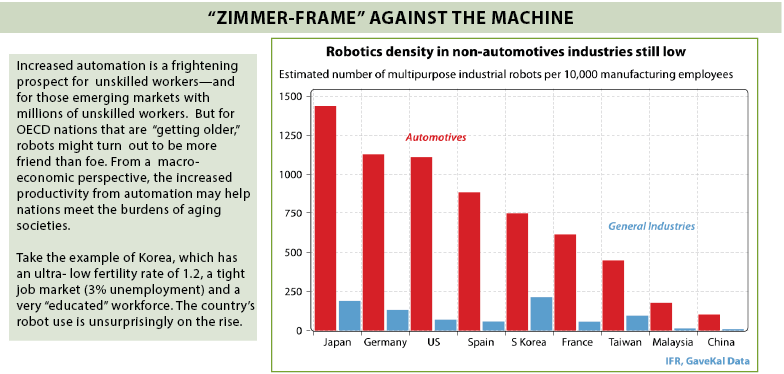

Automation is helping other aging nations meet demographic challenges. In Japan, more than 22% of the population is already over 65. Despite a dwindling number of workers—it is one of the few countries where the population is actually shrinking—Japan is still a major producer of goods and services, thanks in no small part to robots (see chart below).

Korea has a lower fertility rate than Japan, and thus eventually will have an even tougher demographic profile. So perhaps it is no surprise that Korea is a leader in non-automotive industrial robot use. In a country that will eventually “run out” of working-age folk, Korea also has robots acting as military guards, tutors, housekeepers, and even destroyers of invasive hordes of jelly-fish on its coastline.

The US is increasingly experimenting with the automation for services (especially defense services). As an example, robotic surgery has increased by 400% between 2007 and 2011. The image of a “robot surgeon” is a fitting one for a future with a fastgrowing elderly population and a slow-growing worker-age one. A more automatized economy is not just about coffee baristas losing jobs: it is also about raising productivity to meet future needs when available manpower will shrink.

So yes many OECD workers are now “racing” against the machine. But in one short generation they will be “Zimmer-framing”* against the machine. Best to start the race now. For these aging societies, there may be no area of economic development more important than “The Machine.”

* ”Zimmer-framing” is a British nickname for a walker.

US: CAN WE KEEP CLIMBING THE WALL OF WORRY?

Will Denyer

Data was mixed, Washington remained dysfunctional, but corporate earnings were decent and the Fed stayed incontinent. Despite this muddled state of affairs, equities made new highs. So it was another normal week in the US, but did we learn anything new?

The data was clear on one thing: normalized interest rates (and in turn normalized housing affordability) is putting a significant damper on the residential property market. The most concrete sign yet was pending home sales falling –5.6% Month-over-Month in September.

ADP estimated that only 130,000 new private jobs were created in October. In turn, expectations are similarly low for this Friday’s official payroll report.

The bright spot in the data was Institute for Supply Management’s (ISM) manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index (PMI), which rose for a fifth straight month, to 56.4 in October. However, Markit’s PMI is going the other way, posting its third consecutive decline, to just 51.8 in October. Unfortunately, we are inclined to trust Markit’s more lackluster PMI, because the sample size is larger and since it better correlates with actual quarterly growth in industrial production.

Meanwhile, equities pushed higher, and why shouldn’t they? Lackluster growth, resulting in more Fed easing, has been a sure fire winner for equities. This relationship may continue, but a few things worry us.

Even our resident bull Anatole fretted this week that the equity rally is getting long in the tooth. And as we approach the year-end, there is the concern that money managers may lock-in gains and reduce exposure so they can enjoy their holidays. They can return in January to see whether Washington is in another budget standoff or not, and whether it matters.

Another concern for investors’ assumption that Fed liquidity injections can lift all boats is the newly proposed Liquidity Coverage Ratio. This measure means that banks may soon have less freedom in the way they use liquid funds. The Fed exit strategists have been coming up with creative ways to mop up liquidity when the time comes to tighten (see Fed To Ease While Tightening). But the LCR may simply require banks to keep the new money in reserve, or buy treasuries (taking over purchases from a tapering Fed?). Some private sector high-quality-liquid assets (HQLAs) are allowed as coverage, but with limits and haircuts. We do not disagree with the intent of mitigating liquidity crises and bailouts. But if recent equity market gains are indeed the result of liquidity injections, it is worth noting that these funds may soon be tied up or directed to the public sector.

STOCKS AS A LAGGING INDICATOR

Charles Gave

Stock markets are, by nature, leading indicators of future economic conditions. They are the first responders to changes in financing rates, demand, inflation expectations, etc. So long as returns on future investments are expected to be above the cost of capital, the millions of players in the stock market will bid up equities. If marginal returns move below the cost of capital, the market will go down, and so eventually will the economy.

Fine. Except that today, this is no longer the case. In the US, the stock market has become a medium through which the Federal Reserve attempts to convince the world to start spending and investing again. By manipulating the cost of money to drive up the price of assets, the hope is that the “wealth effect” will kick up demand for goods and services in the real economy.

This is NOT the old system at all:

• In the past, higher demand for a product led to a higher return on invested capital (ROIC) for the product’s maker, and then to a higher share price.

• Now, we have an artificially low cost of capital leading to a higher share price, with the hope that this will increase demand and in turn boost ROICs. In order to do this, the Fed is maintaining the cost of capital at zero, with the objective of guaranteeing returns for even the most hopeless company.

• We have moved from a system where the ROIC was key—to one where the manipulated cost of capital is key.

In simple terms, this means the stock market can no longer do its job of screening the bad from the good companies (those which have a ROIC above the cost of capital for their next investment). Instead, the value of the total stock of capital is rising in an indiscriminate way. Without creative destruction, we will have more unproductive companies sucking up resources. Without the benefit of rising productivity rates, we will ultimately end up with a slower structural growth rate.

What will happen if the Fed decides that it is time to let the markets do their job again? The answer is obvious. The cost of capital will rise. Companies that cannot make money without the benefit of free money will cut investments massively. Investors will sell their shares. A long and painful bear market will ensue.

But with markets lulled to a state of stupor by the constant infusion of liquidity, all this will not occur until after any such Fed decision. The stock market has become a lagging indicator of Fed actions.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This report is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any securities mentioned herein. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. All of the recommendations and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions as of the date of this presentation and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Information contained in this report has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, Evergreen Capital Management LLC makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness, except with respect to the Disclosure Section of the report. Any opinions expressed herein reflect our judgment as of the date of the materials and are subject to change without notice. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments or strategies to particular clients. Investors must make their own investment decisions based on their financial situations and investment objectives.