“The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help’.” -RONALD REAGAN

“Being a neighbor to Illinois is like living next door to the Simpsons.” -Former Indiana Governor MITCH DANIELS

Long-time EVA readers know that I am an unabashed admirer of my friend and partner, Charles Gave. Recently, I had a chance to chat with him in Whistler at the annual Gavekal retreat and, even though he is knocking on the door of the three-quarter century mark, he has not lost his wit nor his willingness to challenge prevailing orthodoxies.

Around the time we were up in Whistler, Charles authored the piece which is the basis of this month’s Gavekal EVA. His main tenet is simple but significant: if a country wants faster growth, it should minimize government’s “helping hand”. The charts he cites in the pages below are proof positive, in my view, that he’s correct—despite how many prominent economists vehemently argue the opposite.

The current cataclysm in Venezuela is one example that enforces Charles’s thesis, and it undermines those who argue for even more government control over—and interference with—economic activity. On almost a daily basis, we read of the heart-wrenching deprivation afflicting a nation that was once among the richest in the world. In fact, Venezuela possesses oil reserves that rival Saudi Arabia’s. Yet, today, the once-proud country is crumbling before our eyes thanks to the hard-left shift that began under socialist firebrand Hugo Chavez and has continued under the iron-fisted regime of his successor, Nicolas Maduro.

A kinder, gentler version of this “failure-by-socialist-policies” has evolved—or, more accurately, devolved—over the last few decades in Charles’s home country of France. The government now comprises roughly 60% of the economy and, as Charles reports, its economy has stagnated for decades. Encouragingly, the French people are energized by a new young president who has promised to de-socialize France. In June, voters handed him a landslide parliamentary victory to jumpstart his reform-minded agenda. If he’s successful—a very big “if” based on France’s traditional abhorrence of reduced benefits and longer work hours—it would be excellent news for Europe and the world at large. It would also serve to further validate Charles’s view that too much government is the problem, not the solution.

For Americans, the call for increased government gained momentum leading up to last year’s Presidential election. Self-proclaimed socialist Bernie Sanders wooed many young (and some not so young) voters into rallying behind this ideology. But Americans don’t have to look to France or the Southern Hemisphere to see the ill-effects that runaway spending and ever-escalating taxes have on an economy.

We can simply watch what’s occurring in Puerto Rico and Illinois to realize that increasingly irresponsible economic policies inevitably fail. Eventually, a swelling number of productive individuals and companies depart for less hostile environs, putting more pressure on safety-net programs for those who stay behind and pushing taxes even higher. In fact, over the last decade, 600,000 workers have fled the Land of Lincoln in search of greener pastures. For years, there have been warnings of the death-spiral this ultimately causes…and “ultimately” seems to be “now” for some of the more flagrant practitioners of quasi-socialism.

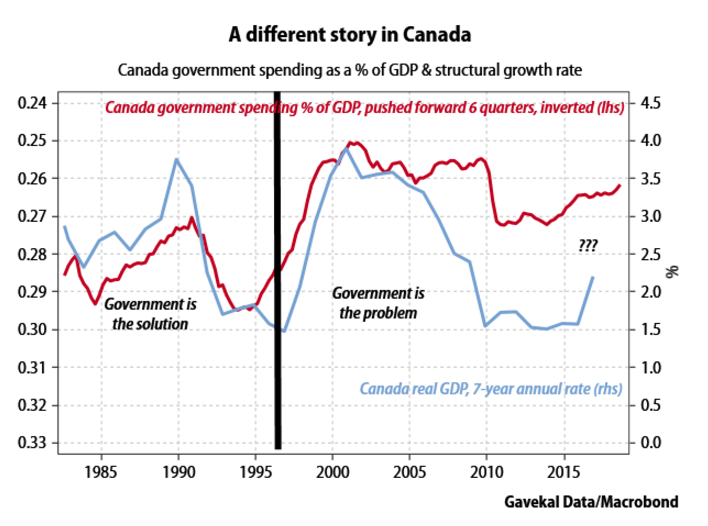

As Charles points out, our good neighbors to the north followed the Illinois/Puerto Rico model until the mid-1990s. At that point, Canada was being derided as an “aspiring” banana republic while its currency was equally disparaged as the northern peso and its credit rating was on the verge of being downgraded to junk. In response, its Liberal party got its fiscal house in order and an economic recovery began a few short years later. (This shows that conservatives don’t have a monopoly on rational economics.)

Today, Canada is among the shrinking number of developed countries that possess the coveted AAA credit rating. Further, it was never forced to bail out its banks or resort to QEs (quantitative easings, aka, printing money). And while the US has been struggling to grow at even 2% lately, Canada has begun cranking out 3%-plus GDP growth numbers—despite the oil bust that has clobbered its substantial energy industry.

Coincidentally, today is the 216th birthday of the great French economist, Frederic Bastiat, whom Charles Gave holds in the highest esteem. Though he is not nearly as well-known as his British contemporary, Adam Smith, Mr. Bastiat was an ardent and articulate defender of incentive-based economic systems. He was also one of the most acerbic critics of what I call “sounds good, works bad” government policies. (To read an excellent article on Bastiat, please click on this link.)

It’s amazing that two-hundred years later, so many policy-makers around the world continue to make the same mistakes Frederic Bastiat warned about in the early 1800s. But, as the French like to say, “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” … “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

SO, WE ARE IN SECULAR STAGNATION...

By Charles Gave

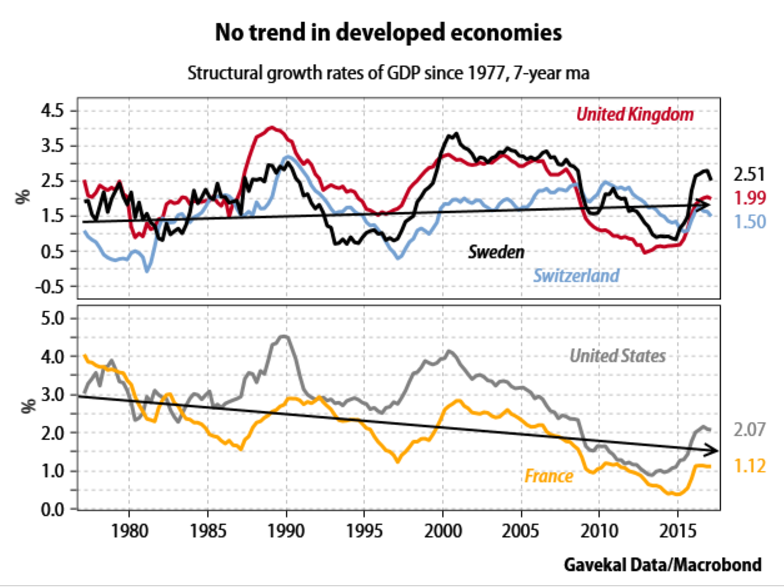

…really? I would advise readers to consider the chart below.

On first blush, its lower pane supports the stagnationist camp. After all, both the US and France have seen a slump in their “structural” GDP growth rate, as shown by the seven-year moving average. Since 1977 this measure has fallen by a third in the US, and by two thirds in France. Yet, look at the chart’s top pane and it is clear that this growth slump has hardly been generalized. Since the late 1970s, Sweden, the UK and Switzerland have seen their growth rates rise structurally, and the same pattern can be found with Canada, Germany and Australia.

Cause and Effect

So why have certain economies tumbled into relative decline, while others have not? A useful approach may be to compare France and the UK, which are similar in size, population and demographic profile. Both countries are European Union members with big banking sectors that in recent decades have had to manage profound de-industrialization.

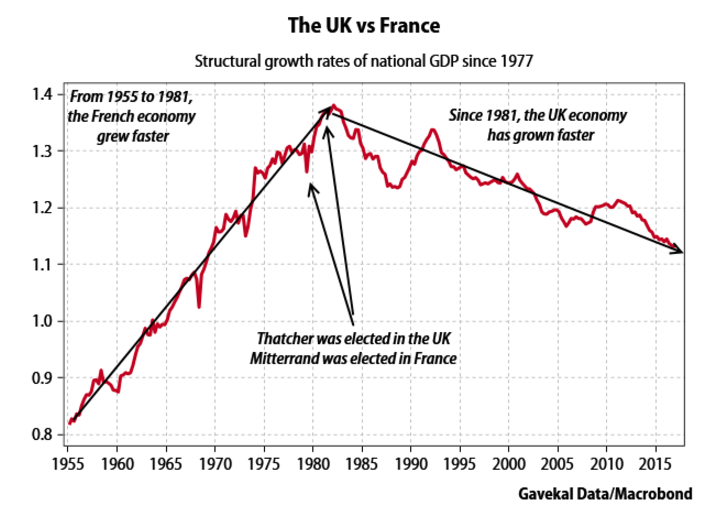

Consider the chart below which shows a ratio of real GDP in France and the UK. No adjustment is made for currency movements as this will introduce unnecessary noise into the analysis. The obvious point is that between 1955 and 1981, France’s economy massively outperformed the UK’s. Since 1981, the reverse has been true.

The trend change corresponded to a political shift in both countries as to the proper role of the state. Under Margaret Thatcher, the UK forged a new path by lessening the role of civil servants in managing economic activity. In France, François Mitterrand expressly aimed to expand the scope of government.

To be sure, the UK Labour Party got back into power in the late 1990s and spent the next decade running socialist policies that caused government spending as a share of output to rocket higher. Fortunately, sanity was restored after 2010 when a Conservative-led government dialed back UK public spending. In France, the picture is different as there have not been politically-inspired changes in the trend of government spending—the ratio has simply ground higher, irrespective of who was in power.

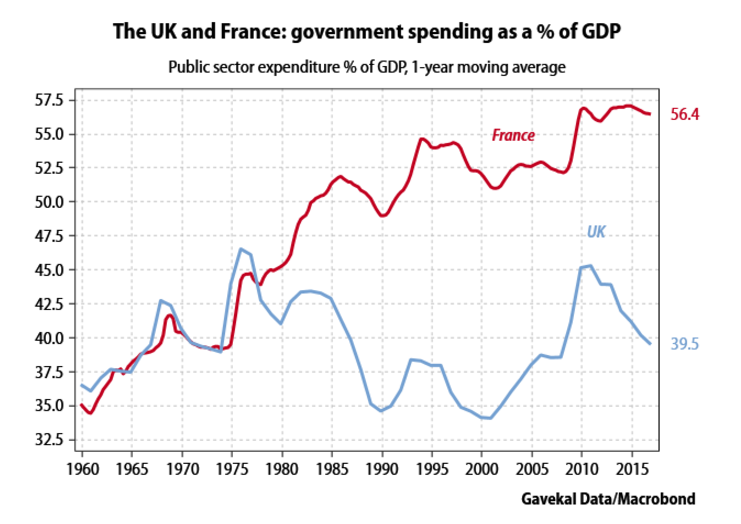

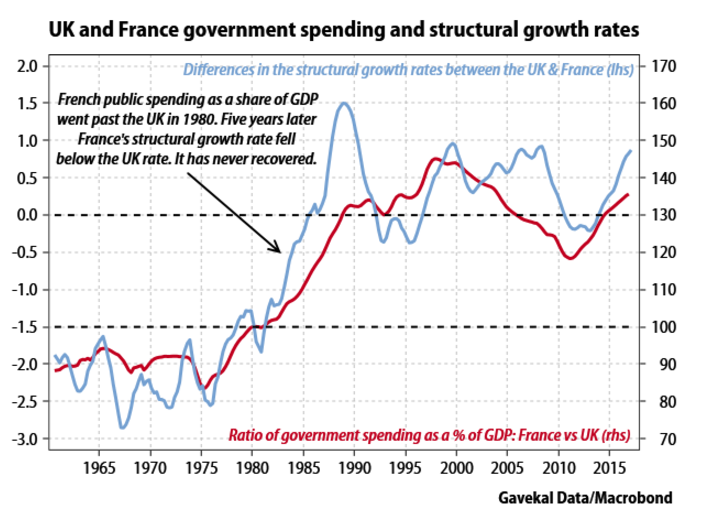

The next task is to explore potential cause-and-effect linkages between public spending and the divergence in the structural growth rates of France and the UK. As such, consider the chart below which reconciles growth and government spending in the two economies.

The chart above shows that in 1980 France started to spend more on government than the UK. By 1985, France’s structural growth rate slid below the UK rate and has not recovered. The logic behind this chart has been borne out in many economies: beyond a certain threshold (that varies by country) more state spending causes the structural growth rate to fall. This relationship follows, as in a government-dominated economy “destruction” of inefficient activity is all but impossible, which in turn limits the scope for fresh “creation”. This insight was explained by Joseph Schumpeter in his 1942 book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy.

What about the US?

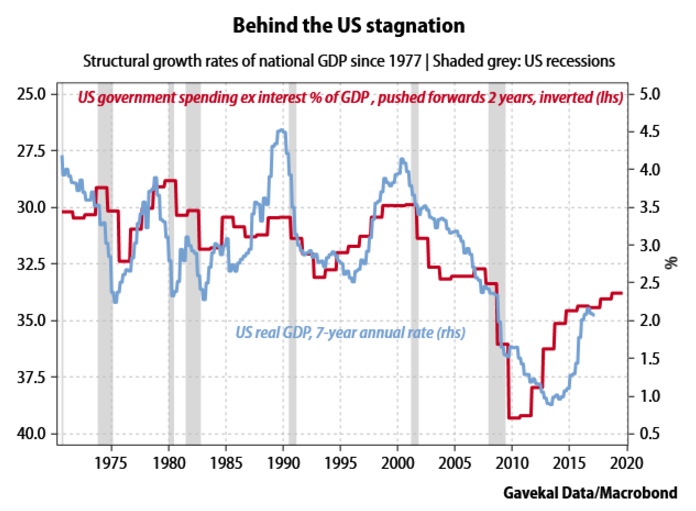

In the US, a similarly straight forward picture emerges, with the big increase in government spending that took place after 2009 being the main cause of the subsequent decline in the US’s structural growth rate.

By way of contrast, consider the reverse case of Canada, which in the mid-1990s slashed government spending to good effect. In two years Canadian government spending was cut from 31% of GDP to about 25%. The ensuing 18 months saw predictable howls of protest from economists that a depression must follow. In fact, not only was a recession avoided but Canada’s structural growth rate quickly picked up and in the next two decades a record uninterrupted economic expansion was achieved.

As an aside, I would ask readers to cite one case in the post-1971 fiat money era when a big rise in government spending did not lead to a structural slowdown. Alternatively, if they could cite an episode when cuts to public spending resulted in the growth rate falling. I am always willing to learn and change my mind!

To conclude, “secular stagnation” is an idea of ivory towered economists. Schumpeter showed how bloated government and unnecessary regulation crimps activity. The perhaps unfashionable answer remains to privatize state enterprises, deregulate markets and break up too-big-to-fail banks. In simple terms, some government is good; too much government is bad.

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.