"I am somewhat concerned about the complacency in the market. ... The stock market still seems to be running very much on fumes…so something that clearly is a risk to the U.S. economy, some correction there, is something that we have to be prepared for."

-JOHN WILLIAMS, San Francisco Fed President on June 27th, 2017

"The Federal Reserve is clearly trying to send a message to the US equity market, but the blind buyers appear to be deaf as well. We cannot recall an instance in our more than two decades in this industry when both the Fed Chair and the Vice Chair has each referred to asset values, especially equities, as expensive on the same day."

-MIKE O’ROURKE, Chief Strategist for Jones Trading

"If the Fed has been adept at anything in the past three decades, it has been to create bubbles and then destroy them."

-DAVID ROSENBERG, Canadian celebrity economist

Introduction Every so often, I like to summarize our “CinemaScope” view of current conditions. Perhaps these days it should be called our “IMAX outlook”, but the point is to try to pull together our big picture perception of the financial and economic landscape.

First, a big disclaimer: In recent years, I have repeatedly acknowledged that the post-global financial crisis (GFC) period has been characterized by interest rates at levels previously unseen in human history, even going back to the before-Christ epoch. Similarly, the world has never experienced such radical and untested monetary experiments by central banks as they have vainly valiantly striven to return global economic growth to its pre-GFC trendline. Accordingly, none of us alleged experts have ever witnessed this particular set of circumstances, rendering our opinions on the future course of economies, markets and inflation even more suspect than usual.

Ok, enough with the alibis. Let’s get to the facts on the ground, including some that are 180 degrees opposed to what we’ve seen for almost a decade.

Note: Our “Pull it together” EVA will run as a two-part issue. The second-half of this EVA will be published next week, on July 14th.

Can’t get no…satisflation. Consumers and central banks seem to have a very different view of inflation. Buyers of goods and services favor the prices of what they regularly purchase to either remain constant or, preferably, decline. The planet’s monetary mandarins, however, detest the thought.

Their reasoning is that stagnant or, God forbid, deflating consumer prices are alarming, particularly during an economic expansion. This is because during the next downturn (yes, those still happen) deflation could become widespread and intense, causing businesses and individuals to curtail their purchases in the expectation of even lower prices in the future. The ultimate central bank nightmare is that this sets off a self-reinforcing doom cycle, grinding economic activity down further and further, with their monetary tools proving increasingly impotent. The net result is a repeat of the Great Depression. (Students of history could rightly object that deflation was the norm prior to WWI – and the creation of the Fed in 1913 – an era of rapid worldwide growth.)

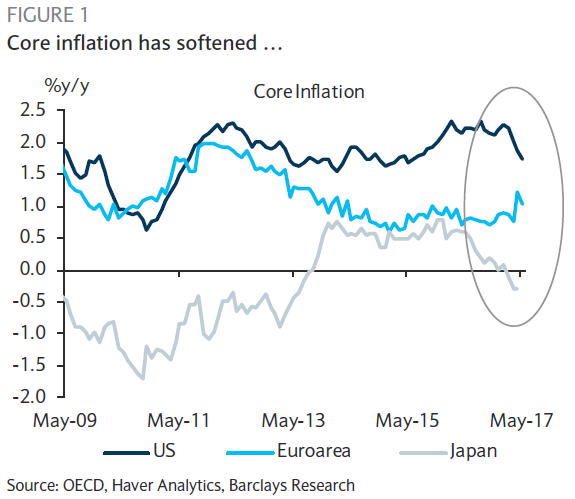

Consequently, central banks have been obsessed with forcing the CPI in every developed country back up to 2%. Yet, I can’t come up with a case where they’ve hit their mark. This is despite (or, as renegade thinkers such as Charles Gave and Jim Grant would contend, because of) multi-trillions in freshly minted government IOUs and almost equally staggering sums of “magic-wand” money fabrication.

Source: OECD, Haver Analytics, Barclays Research

Source: OECD, Haver Analytics, Barclays Research

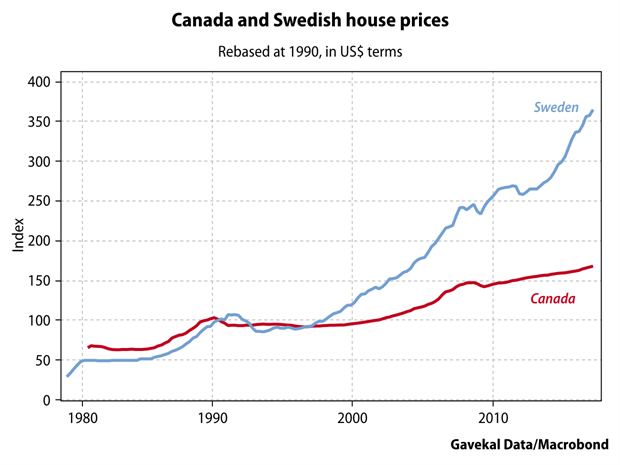

But, as repeatedly noted in prior EVAs, they’ve been spectacularly successful in generating asset inflation, particularly with real estate nearly everywhere and in US stock prices. Realizing that frigid little Sweden isn’t exactly top-of-mind for most Americans, it’s nonetheless an interesting case study in this phenomenon, for a few reasons.

For starters, Sweden, like Canada, was a poster child of constantly increasing socialism until the early 1990s. What slammed the Swedes’ faith in their prevailing economic path was a monstrous housing bubble and implosion nearly 25 years ago; in other words, it was about 15 years ahead of what the rest of the world would experience in 2008.

Predictably, this caused the virtual extinction of the Swedish banking system, requiring a huge—and hugely unpopular—government-sponsored bank bailout. But it also caused serious soul-searching about the economic policies the Swedes had been following since WWII. Much like Canada at almost precisely the same time, Sweden began to overhaul its legendary cradle-to-grave welfare state. The result was a vigorous and long-lasting economic expansion.

Now, fast forward to today. Unlike most developed countries, Sweden isn’t limping along at 1% to 2% “growth”. Rather, it is sprinting at a 3%-plus clip and proudly stands among the elite nations with a AAA rating from all credit agencies (unlike, for example, the US which was downgraded by S&P several years ago). By sheer coincidence—or not—this is exactly the rarefied status Canada finds itself in today.

But the most relevant similarity is the two countries’ housing markets. To say they are strong is sort of like observing Stephen Curry is a decent basketball player. In fact, Sweden’s makes Canada’s look lukewarm by comparison.

Hedge funds have been shorting Canada with a vengeance, particularly Canadian banks, for years based on the housing bubble premise. We’ve argued that they are missing the reality that outside of Vancouver and Toronto (both irresistible magnets for Chinese money), the rest of Canada’s housing isn’t all that fizzy. Sweden, though, is a different story with virtually the entire country caught up in the frenzy. This is almost certainly a function of the Swedish central bank holding interest rates near zero despite a rollicking economy.

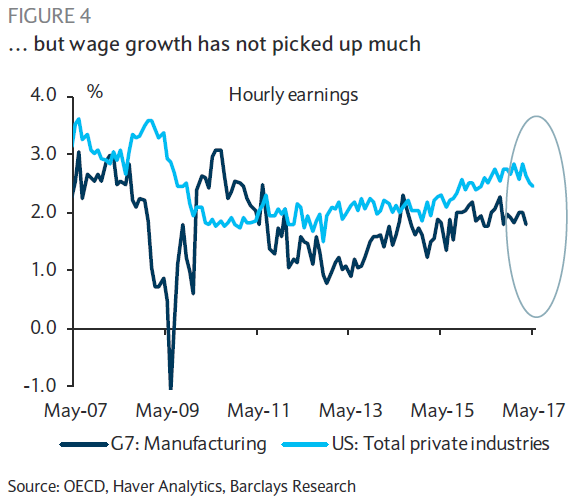

While Sweden is an extreme case, it’s far from unique. China, Australia, much of Europe, and, of course, many cities in the US are also in the throes of a full-throated bull mania in housing. Ironically, since housing is such a large component of the cost-of-living (especially when including the related rent factor), this is one of the few upward pressures on consumer prices. Yet, like healthcare, it is an essential outlay. So, as housing and medical costs go postal this squeezes discretionary spending, which suppresses both core inflation and economic activity. (Rents are up over 60% since 2010 in Seattle, for example, far outpacing wage gains.) In other words, monetary policies are back-firing.

The scarier scenario is that central banks are waking up to the fact that there is no painless exit from the tiny and terrifying corner into which they’ve printed themselves. Just this week, the heads of both the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England received a sobering dose of Ben Bernanke’s “taper tantrum” blow-back four years ago when he merely hinted at the possibility of ending his string of QEs (quantitative easings). Of course, as timid as monetary poohbahs are these days, whenever markets hiccup, they immediately try to walk investors back off the ledge. Undoubtedly, their highly practiced communication skills will do the trick…for now.

Do spook the markets! Frankly, this is another example of how badly hemmed in the monetary magicians are by their years and years of untested bold stimulus programs. If they leave the spigots open, asset prices will continue to climb the proverbial hockey stick. If they start to shut them down, investors panic.

Well, actually, there is an exception to the latter part – and that’s the US. A person would have to be on a Tibetan trek or a WiFi-free oceanic cruise not to notice that the Fed has had a personality change worthy of Miley Cyrus over the last six months. We’ve been warning about this pretty much ever since the presidential election. But, what was once an isolated view has now become broadly accepted. As you’ve no doubt noticed, though, this recognition has done absolutely nothing to dampen investors’ raging hormones.

These blithe spirits in the face of four Fed rate hikes, with more projected to follow AND, as we’ve been warning, the virtual certainty of a double tightening (i.e., both rate hikes combined with reversing some of the QE trillions), are a mixed blessing. On the one hand, they are giving the Fed cover to tighten further and utter ever more bellicose comments. On the other, they are clearly frustrating Yellen and Co. who now can’t seem to create even a taper grimace, much less a tantrum.

As usual, I believe the culprit is the Fed itself. Past EVAs have noted that Yellen has publicly confessed that the Fed blew it during the 2004 – 2007 bubble build-up by raising interest rates so gradually, and with copious amounts of advanced warnings, so as not to spook the markets. These were the years when Alan Greenspan was in the process of passing the baton to Ben Bernanke and, of course, when the US housing market was en fuego to the max.

The maestro commented on this at the time with considerable—but considerably misplaced—satisfaction. “The market pretty much anticipates how we’re going to respond to various events,” he purred in May of 2005, boasting that his fully telegraphed tightening moves were causing “as little (market) reaction as possible.”

The above quote is from a must-read Wall Street Journal article in the June 24th, 2017 edition by Sebastian Mallaby (click here to access). For those who don’t have the time to read it, he persuasively makes the case that even when the Fed tightens a lot—as it clearly did in the housing bubble years by raising its overnight rate from 1% to 5 ¼% —if it moves slowly and predictably markets don’t get rattled. Or at least they don’t get spooked until far too late, when asset prices have become so high that they pose systemic risks once they crash—as they always do when they fully detach from fundamentals.

Yet, despite Janet Yellen’s “our bad” admission, she is presiding over exactly the same process. As Mr. Mallaby sagely writes: “By being less transparent—and reserving the option of deliberately ambushing investors with a shock move—the Fed could discourage them from taking too much risk. Such an ambush would unsettle markets to be sure; but that would be the point. The painfully learned lesson from the late 1990s and mid-2000s is that excess financial serenity leads to excess risk-taking, which in turn increases the chance of a blowup.”

The problem is, as we will see shortly, it’s too late for a graceful exit by the Fed. While Mr. Mallaby doesn’t explicitly state that, he notes, “With every passing month, the US economy feels like it did in 1999 and in the mid-2000s.” In reality, that’s been the case for a few years and only now, after the sandcastle of mass speculation has built up to truly precarious proportions, is the Fed realizing what it has wrought.

Last week Yellen & Co made it Swarovski-crystal-clear that asset prices are too high and investors are ignoring its clamp-down efforts at their own peril. One could say this is just a repeat of Alan Greenspan’s 1996 “irrational exuberance” comments, after which the market more than doubled over the next three-plus years. But this sunny view is to ignore that the economy and asset prices are much, much more late cycle than they were in 1996. Markets were also not facing a double-tightening back then, a truly historic development—and threat.

Maybe it’s just paranoia caused by having lived through the last two times the US stock market was cut in half, but when I read the following words from the head of our central bank, I get that gut-punch feeling: “Asset prices can move, they can cause losses to individuals who decided to invest in things that fall in price, but we’re worried about systemic risk and with a strong banking system those kinds of repercussions are not at the top of my list.” But this was the really scary part, in my opinion: “Would I say there will never be another financial crisis, probably that would be going too far. But I do think that we are much safer and I hope that it will not be in our lifetime and I don’t believe it will be.”

Putting aside the irony that for years the Fed did everything it could to get even risk-averse investors to “invest in things that fall in price”, the fact that she only thinks that it’s “probably” going too far to think there will never be another financial crisis and that she doesn’t think it will be in “our” lifetime is truly astounding. Those words seem as destined to come back to haunt her as Woodrow Wilson’s (or was it H.G. Wells’?) “WWI is the war to end all wars” and Ben Bernanke’s “housing problems are contained in sub-prime”.

Don’t those ivory tower eggheads at the Fed understand something as basic as the overconfident jinx?

We don’t need no stinkin’ trillions. A quick question for all you highly-informed investors: When was the last time you heard “Don’t fight the Fed”? Even though my team and I are overzealous trackers of financial analysis, last week we collectively said, “Can’t remember.” Somehow, this supposedly essential truism has disappeared from the lexicon of the commentating community.

From 2009 until 2014, this was the dominant mantra and it worked—at least once the Fed started pumping out QEs by the trillions. Previously, however, as the Fed began frantically cutting rates in mid-2007, when housing fell off the cliff, stocks did the same despite the fed funds rate being slashed all the way to ¼%. In other words, the Fed cut short-term rates by 500 basis point (5%) and all that Fed easing did nothing to stop the S&P falling by nearly 60% from peak to trough.

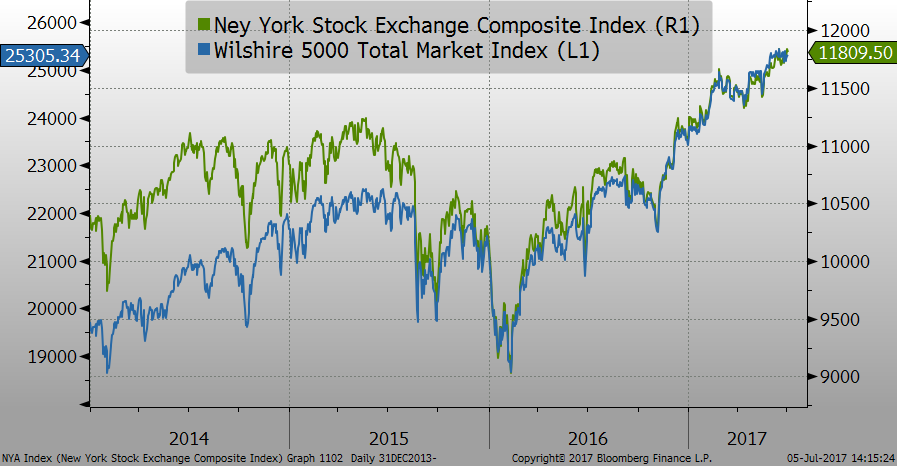

But once the Fed began its tapering in late 2013, the market paused a few times, churned a bit, and then, last November, broke out to new highs. EVAs circa 2014 to Q3 2016 pointed out that the broader market indexes, like the NYSE Composite and the Wilshire 5000, had gone nowhere for several years.

Then along came The Donald and the trading range was decisively shattered—to the upside, naturally. His election became the rationale for this latest bull run, but it was just one of many trotted out over the years to justify stocks trading at some of the loftiest valuations ever. First, was the aforementioned “Don’t fight the Fed” storyline.

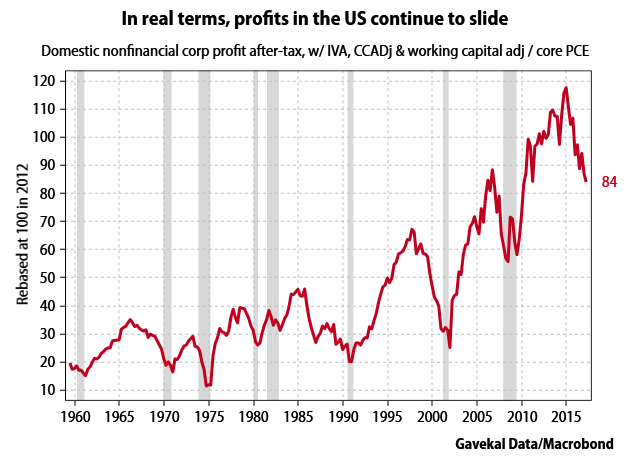

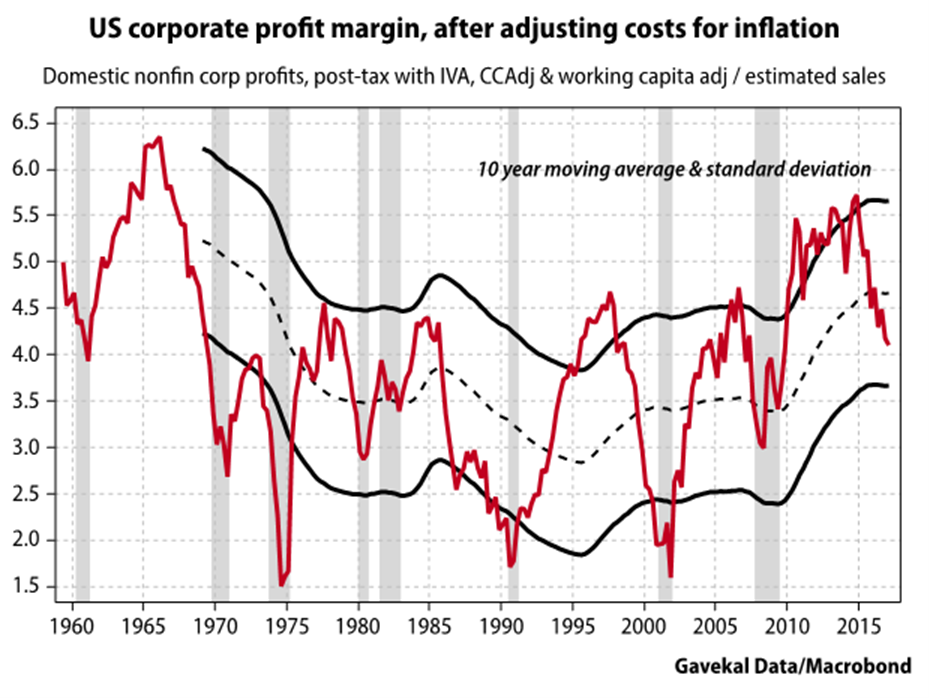

Next were earnings and that was arguably the most valid narrative. Over the first four years or so the bull market surged to new all-time highs with profits creating a healthy catalyst for the rally. By 2013, though, Evergreen began to sense profits and profit margins were topping out. As you can see below, our concerns were valid.

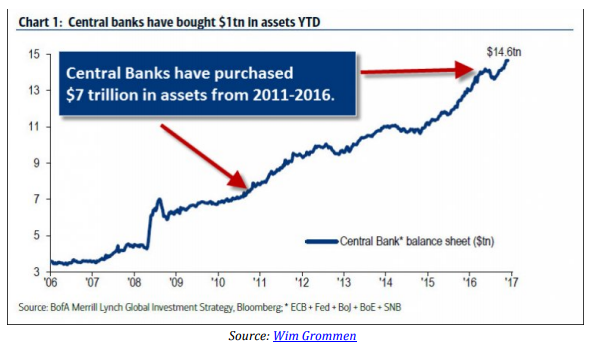

We felt this, combined with the suspension of the Fed’s QEathon, were plausible grounds for a market shake-out. In the summer of 2015, and again in early 2016, our angst was briefly justified. But then overseas central banks came to the bull market’s rescue. Per the below chart, the synthetic trillions just kept coming.

Source: Wim Grommen

Source: Wim Grommen

As I’ve expressed before, you have to give this bull credit for being able to effortlessly morph from one upside driver to another:

Along the way there has also been some enthusiasm about “escape velocity” from the sub-par economic expansion we’ve been in, the worst since WWII. (By the way, the economy has expanded by a mere 1.3% annually over the past ten years, the worst since the decade of the Great Depression, despite $10 trillion of fresh federal debt, that accounted for over half of that meager growth, and, of course, QEs I, II, and III). In every instance, those hopes have flamed out, including the so-called Trump Bump. Ergo, we continue to be stuck with the limpest economic expansion of all-time coinciding with a bull that has been much stronger than the post-war average. Kind of tough to reconcile, no?

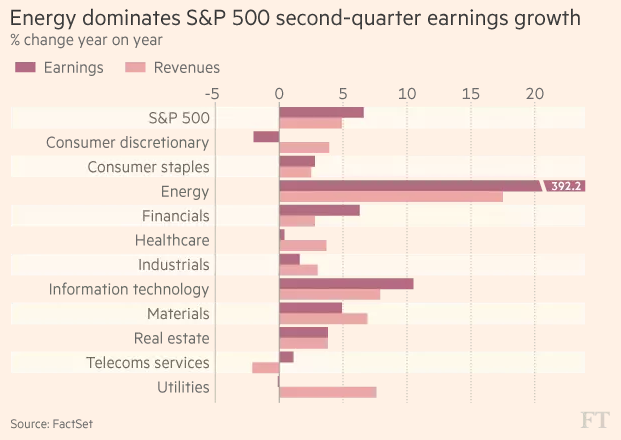

But with earnings again being cited as the current reason for strong stock prices, it’s reasonable to wonder if this isn’t a higher quality and more durable market propellant. The problem is, as we’ve commented previously, profits are being flattered by a comparison with a very soft first quarter of 2016. Additionally, the most vigorous earnings bounce has come from the energy sector which is, once again, almost everyone’s favorite piñata. It has been beaten down to where it represents just 6% of the S&P and yet it is contributing 40% of this year’s net income jump. Moreover, excluding the snap-back in energy-related capital spending, the US economy essentially flatlined in the first quarter.

ENERGY POWERS S&P 500 EARNINGS

Source: Financial Times, article by Nicole Bullock

Source: Financial Times, article by Nicole Bullock

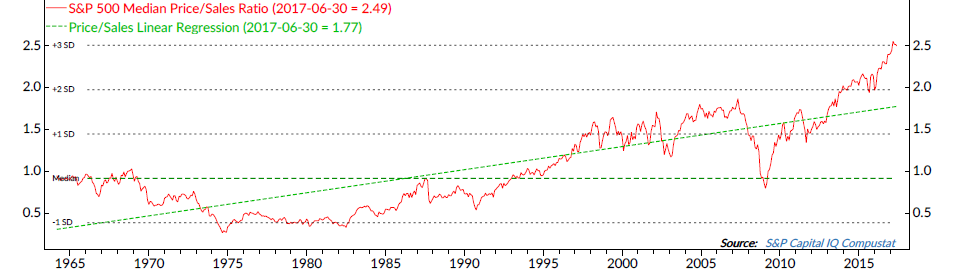

This rediscovered focus on profits—and profitability—has also caused many bulls to blow off Evergreen’s number one valuation concern: the highest median price-to-sales ratio ever. Their argument, to which there is some validity, is that because profit margins are in a long-term uptrend, then price-to-sales concerns are overblown. The problem with this is that the extent of the premium of price-to-sales now vs. history looks ridiculous presently. Also, please note how it has gone vertical over the last few years as profit margins have gone the other way.

S&P 500 INDEX VS. S&P 500 MEDIAN PRICE/SALES RATIO

There are already indications the earnings rebound is losing its bounce. To say there is substantial scope for disappointment is an understatement. Operating earnings were $106 last year, down slightly from 2013. In other words, they’ve been flat for three years, even using the non-GAAP version (i.e., excluding all the bad stuff from profits that make it harder for senior management stock options to be “in the money”). By the way, the reported GAAP earnings number for 2016 was $95.

Suffice to say, in roaring bull markets, hope springs eternal. The present consensus (non-GAAP) estimate for this year is $128. That works out to a just a bit—as in, insanely—optimistic 20% increase over 2016. Sure, it could happen (and so could healthcare reform).

But if the second half reverts to the flat earnings trend that has persisted since 2013 (during which the stock market has roared ahead by 40%), bulls will need a new storyline to justify red-giant-like valuations. And, if they can’t come up with a good one, they may suddenly remember what Roman emperor Vespasian said when he sought to generate revenue from taxing public urinals: Money doesn’t smell. For asset prices, it is especially non-smelly—actually, intoxicatingly aromatic—when it’s been created by the trillions. Whether the hyper-confident bulls realize it now or not, someday they are going to miss that scent a great deal.

To be continued next week…

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

Changes in bold.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.