“You don’t make mistakes when you don’t have money. When you have too much money, you will make a lot of mistakes.”

– Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, the Amazon of China

“My view is simple and starts with the observation that gold is a lot like religion. No one can prove that God exists…or that God doesn’t exist…Well, that’s exactly the way I think it is with gold. Either you’re a believer or you’re not.”

– Howard Marks, founder of OakMark, whose newsletter Warren Buffett reads “religiously”

“Because of Paul Volcker, our financial system is safer and stronger. I’ll remember Paul for his consummate wisdom, untethered honesty, and a level of dignity that matched his towering stature.”

– Barack Obama

“Every penny of QE undertaken by the Fed that cannot be unwound is monetized debt.”

– CNBC regular and former senior advisor to the president of the Dallas Fed, Danielle DiMartino Booth

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

40 years is a very long time, at least in human terms. But when it comes to inflation, the not-so-fine 1979 seems like 400 years ago. It was in that difficult year — with spiking oil prices pushing the CPI up at close to a double-digit rate — President Jimmy Carter appointed Paul Volcker as the head of the Federal Reserve. Even in those days, Mr. Volcker was a larger than life figure—in more ways than one.

He stood 6’7” and he had already earned a reputation as a “hard money” proponent, in contrast to the politically-pliant and inflation-prone Fed heads who had preceded him in the wake of the last strong Fed chairman, William Chesney Martin. The latter was one of the few men Paul Volcker looked up to, reputationally if not literally. He also was the creator of the line that in time would become immortal, at least in economic circles: “It’s the Fed’s job to take away the punch bowl just when the party gets going.”

It was Mr. Martin’s propensity to be a punch-bowl cop that got him into hot water in 1965. He was reluctant to monetarily accommodate Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and Vietnam war spending sprees. This resistance reportedly caused LBJ to slam his Fed chairman up against a wall at the President’s Texas ranch, bellowing: “Boys are dying in Vietnam and Bill Martin doesn’t care.”

But care he apparently did. Even as the US economy boomed and inflation began to rise at a disturbing clip in 1966 and 1967, Martin only timidly raised interest rates. It was not until President Johnson shocked the world in March of 1968 by announcing he would not run for re-election that Mr. Martin let interest rates really fly. The Fed’s discount rate popped from 4.7% to 5.6% in just two months, the fastest increase in a decade.

Mr. Martin’s lectures to Congress over his 19-year tenure at the Fed revealed a mindset that likely would have put him at odds with LBJ’s successor, Richard Nixon. At the bottom of one economic slump, Mr. Martin warned Congress that you can't ''spend yourself prosperous.'' (He no doubt would have added or “print yourself prosperous” but that was an activity Mr. Martin likely never dreamed his cherished Fed would one day pursue…and pursue…and pursue…and pursue—that’s a pursue for each version of its Quantitative Easings!)*

*The Fed refuses to call its latest money creation blitz QE 4 but almost everyone else is.

Source: The MacroTourist and David Collum

For good measure, he remarked on another occasion, ''A perpetual deficit is the road to undermining any currency.'' Despite Nixon’s impeccable GOP credentials, Mr. Martin may have suspected an inflationary wolf in sheep’s clothing. He resigned in January 1970, just one year into Richard Nixon’s first term. The next year, Mr. Nixon pulled the US off the gold standard and then proceeded to bully Mr. Martin’s replacement, Arthur Burns, into maintaining excessively low interest rates. This sequence led to Mr. Nixon’s re-election in 1972 but also to the virulent inflation that would haunt America over the next decade. (Do you discern any similarities with what’s happening today?)

Earlier this month, Mr. Martin’s kindred spirit, Tall Paul, passed away at age 92. While most post-mortem commentaries were laudatory, there were a surprising number of criticisms of his anti-inflation campaign which, at one point, raised short-term borrowing rates to 21 ½%. Undoubtedly, many small business owners suffered mightily with the cost of money nearly 10% over the prevailing 12% inflation rate. Some critics even called Mr. Volcker a union-killer, erroneously, in my view, blaming him for the long decline in American union membership that has occurred since the early 1980s.

Of course, interest rates and inflation couldn’t be any different today. Instead of a fed funds rate far above inflation, presently it is below it, even using the Fed’s preferred cost-of-living measure. (More on that topic in a bit). And instead of trying to quash inflation, most leading central banks are striving to force it up to 2% which has, for some reason, become the Holy Grail for the global gods of monetary policy. In most of the “advanced” world, interest rates are negative and, accordingly, well below the inflation rate of that particular country.

One of the shocking surprises of the last decade is that despite ultra-low, zero, or, even, negative interest rates—combined with around $15 trillion of manufactured money—inflation has generally fallen rather than risen. Actually, the popular notion seven or eight years ago, as rates collapsed and central banks began their various Quantitative Easing programs (QE, i.e, digital money fabrication), was that high inflation, potentially of the hyper variety, was nearly certain.

These concerns centered on the CPI and its less well-known corollary, the PPI, or Producer Price Index (basically, wholesale vs retail inflation). Yet, as we are all aware, when it came to asset prices – especially US stocks, global bonds, and real estate—it was a totally different story… except for one slice of the investment world that many thought would be among the biggest beneficiaries of this worldwide attempt to create printing-press prosperity. That would be gold and the other precious metals.

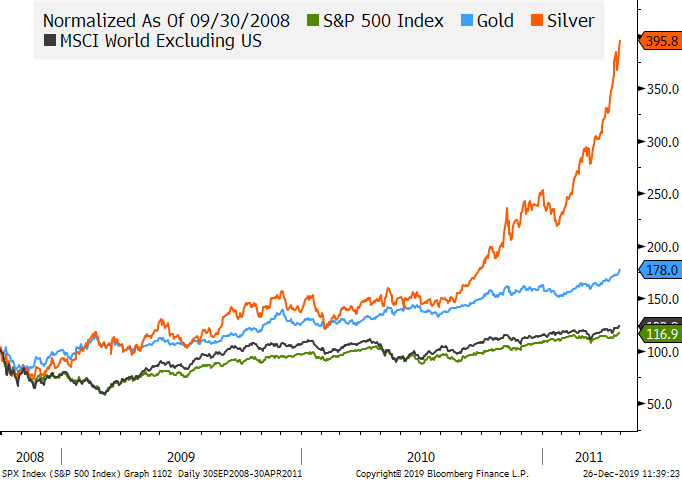

Early on, it looked like the assumed scenario would play out. As QEs spread around the planet in the early part of this soon-to-be-completed decade, the precious metals complex went postal. As usual in bull phases, silver had the greatest surge, rising by 452% from its lows during the Great Recession. Gold’s ascent was less spectacular, but it nonetheless vaulted almost 170% from where it bottomed in late 2008. By the spring of 2011, both were far ahead of global stock markets, including the S&P 500, once again measured from the lowest points of the financial crisis.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

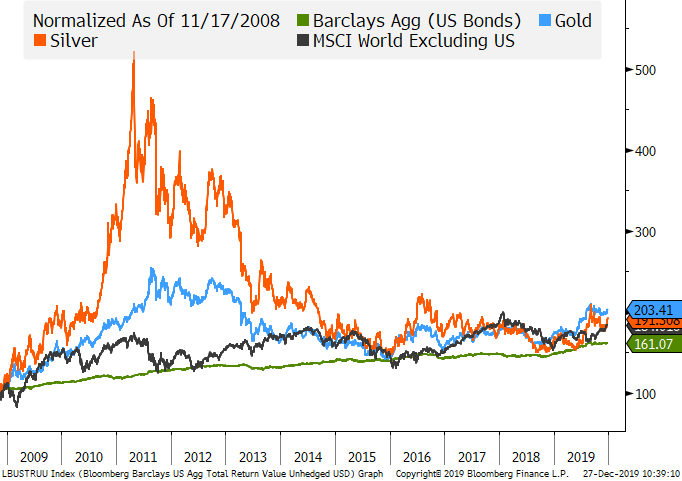

Fast forwarding to right now, it’s a very different story, at least for the S&P. The most revered stock index on the Planet Earth is up a prodigious 498.5% (total return) from its 2009 low-point, while gold and silver have roughly doubled by comparison. However, they do look much better compared to the global stock market index, excluding the US, since then; this is due to how poorly international stocks have performed vis-à-vis the US. (Ironically, in 2011 and 2012, overseas shares were all the rage, especially emerging markets.) On the more embarrassing side, gold and silver returns aren’t that much better than bonds over the past decade, despite having a monster lead in the early years. (Platinum has performed even worse!)

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

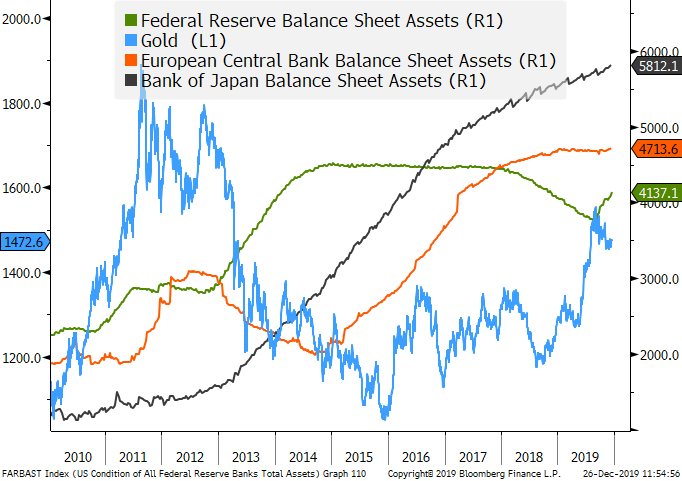

This long performance lag has caused most American investors—be they retail or institutional—to give up on precious metals as an essential asset class. After all, if they couldn’t deliver during a time of ideal conditions (collapsing interest rates and binge-printing by central banks), what could possibly cause them to rise now? (Note: Central bank money fabrication causes their balance sheets to increase.)

Chart of Gold vs Central Bank Balance Sheets

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

For an answer to this reasonable question, it might be helpful to review a summary created by Evergreen’s bright and inquisitive research team member, Michael Schaloum. Michael does this author a great favor by regularly listening to video interviews with many of the investment world’s brainiest inhabitants. He recently watched and summarized a debriefing on Real Vision TV with John Hathaway. For those of you that don’t know of John, he is considered to be the Warren Buffett of the precious metals space. He also lives near our family’s winter home and I’ve had the pleasure of meeting him on two occasions. Here is a bullet-point summary of Michael’s recap:

Though apparently he didn’t mention it, John might have added that the Fed has now launched QE4 even though they refuse to call it that. Just since September, the Fed has whipped up another $500 billion of fake money. In this case, the precipitating factor was severe stresses in the repo, or repurchase agreement, market. This is where banks borrow and lend vast sums to each other on a very short-term basis, secured by treasury securities.

It’s incredible, at least to me, that the Fed feels compelled to both cut rates and print money at a time when unemployment is at a 50-year low and the S&P 500 is cranking out record highs. Its rationale is partially due to fears of another repo market seize-up (which briefly drove the overnight lending rate to 10% in September) and its singular focus on an inflation measure almost no one else tracks, the PCE or Personal Consumption Expenditures.

As storied money manager Stan Druckenmiller said last week, referring to the Fed’s preoccupation with the PCE:

“Well, first of all, there’s 14 recognized measures of inflation. Twelve of them are above 2%. Their preferred measure, the core PCE is at 1.7%. The risks they are taking with regard to misallocation of resources, bubbles, all that stuff because something is at 1.7% as opposed to two, and now they’re talking about a makeup period?”

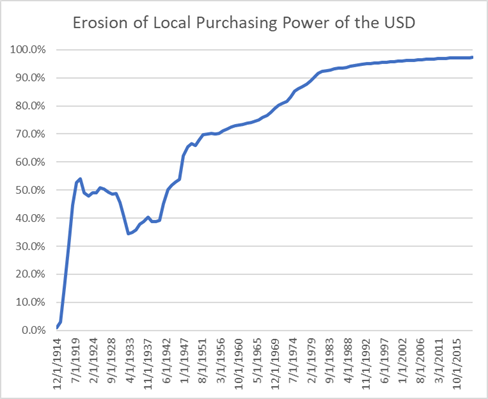

His last point is that the Fed is now openly discussing letting inflation run over 2% for an extended period to compensate, or make up for, the years when it’s been below 2%. Frankly, I continue to wonder why 2% is a good inflation level when it erodes purchasing power in a big way over time. With 2% inflation over a twenty-year timeframe, a dollar depreciates by roughly one-third (compounding works in reverse when a value is shrinking). Long-term, the story is much more dismal.

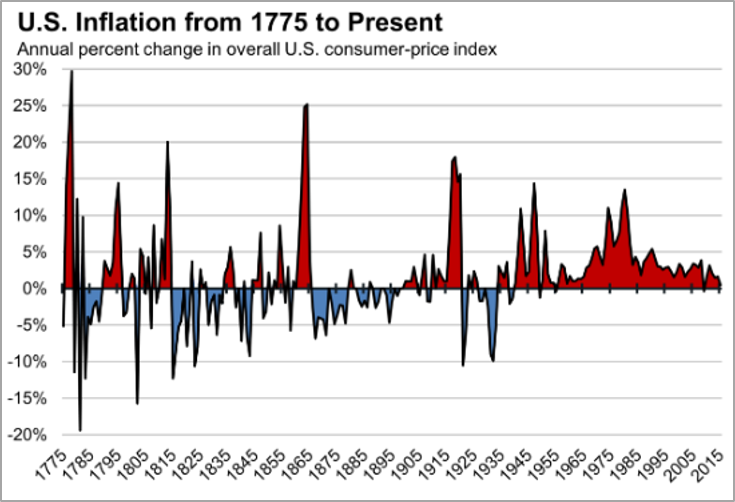

Ironically, prior to the creation of the Fed in 1913, US consumer prices were stable for most of America’s 130-year history, outside of the War of 1812 and the Civil War. The deflation in the non-war years prior to 1913 offset the brief inflation bursts, so that for over a century the dollar roughly retained its purchasing power. Since then, outside of the Great Depression and those eras when people like Bill Martin and Paul Volcker were in charge of the Fed, it’s been all downhill. The US dollar’s purchasing power is less than 5% of what is was when the Fed opened its impressive doors, on the eve of WWI.

Source: WSJ, Labor Department, & Historical Statistics of the United States

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

As Mr. Druckenmiller alludes to, and I wholeheartedly agree with, the Fed’s preoccupation with a debatable and minor shortfall by inflation has led to series of dangerous circumstances, including monetizing the federal debt. In English, this means financing the government’s trillion dollar plus deficits with funds whipped up by the Fed’s magical money machine. As noted previously in these pages, if I’d said years ago that the Fed would be doing this, particularly at a time of decent economic performance, EVA readers would have questioned my sanity…even more than they normally do.

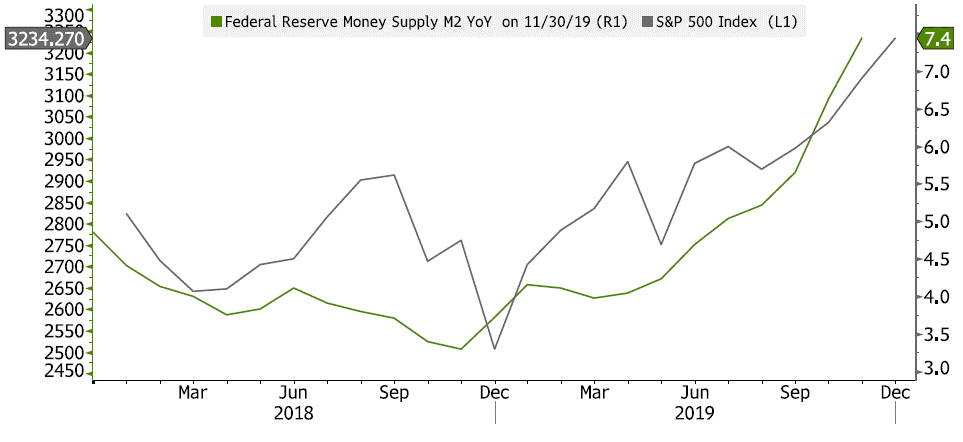

Due to the Fed’s frenzied efforts, the money supply is in a ripping bull market of its own. The correlation between M2 (the main money supply metric) and the stock market recently has been remarkable.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Other central banks have joined in opening up the liquidity fire hose. It’s certainly been glorious for investor portfolios as 2019 winds down but a rational person with a knowledge of history must realize the eventual payback. There’s never been a time in the past when central bank debt monetization hasn’t ultimately led to an unhappy ending. (Sorry for the double negative but this is a topic that deserves serious negativity!) Yet, it seems like almost no one is thinking about the eventual agonizing hangover these days; rather, it’s all about the intoxicating near-term returns.

Referring back to John Hathaway’s comments about entitlement obligations, it’s almost inarguable that either benefits need to be drastically reduced or the US, and other developed world governments, must use inflation to reduce the nominal costs of those and the debt that is used to finance them. Since the former is politically untenable, the latter becomes the path of least resistance. Who seriously believes this current feckless cast of policymakers won’t take the easy way out?

In the short-term, though, we could see a scenario that both John and another very wise man, David Rosenberg, anticipate. In their view, and I suspect they are right, we could have a recession in 2020. This becomes much more probable, in my opinion, should financial markets correct hard next year after this year’s historic and euphoric rally. It’s during the next recession that we are likely to see governments and central banks launch a coordinated blitz made up of additional trillions of pseudo-money (pseu-dough?) and unbridled spending (even more than we have today, which is expecting the truly surreal).

To quote David: “Remember that what follows this period of recessionary deflation will be MMT* or some facsimile thereof. That is the ‘big bomb of debt monetization that ends up sending gold beyond a bull market towards a parabolic surge.” In other words, the next recession and/or bear market (believe me, dear EVA reader these are both certain to happen again) will set off the chain reaction that leads to the atomic event which creates the inflationary burst central banks so dearly desire. It’s likely to be a classic case of “Be careful what you wish for—you may get it good and hard.”

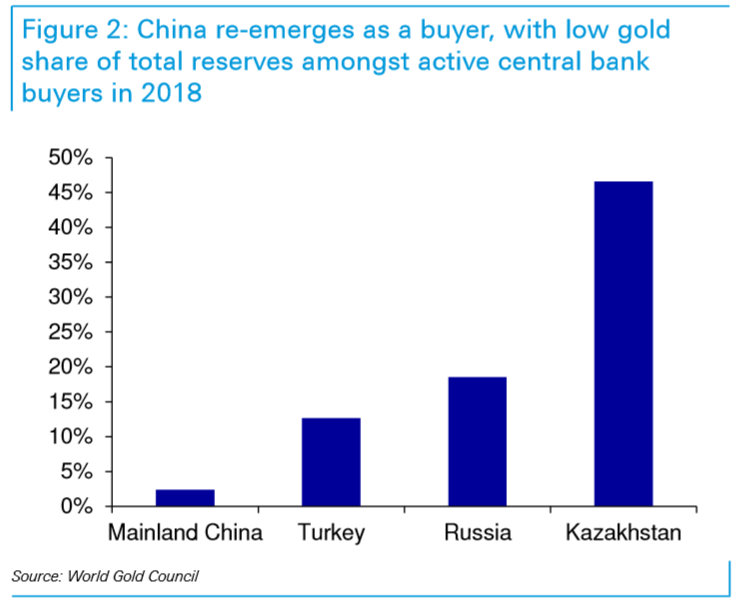

Another rich irony is that the central banks – the very perpetrators of this bizarre world in which we find ourselves, with all of its long-term inflationary implications – are in many cases buying gold in massive quantities. In 2018, central bank gold purchases were the highest in 50 years and 2019 might see a similar pace. Those based in the developing world and in Russia have been the most avid buyers. The former USSR now has almost 20% of its total foreign reserves in the yellow metal.

In China, however, that number is under 3%, implying that gold could become a far larger component. This is particularly true given the trade war with the US and China’s increasingly dim view of the dollar’s long-term purchasing power. (I can’t blame them, can you?)

*MMT, or Modern Monetary Theory, effectively advocates government spending without regard to affordability.

To reiterate a theme from several recent EVAs, Evergreen believes (or at least it’s Chief Investment Officer does) that the next decade will be very different than the past for financial markets. The last 10 years have seen receding inflation and interest rates, both of which have been jet-fuel for bonds and equity sectors such as consumer staples/discretionary, healthcare, and, of course, tech. These all fall under what I would call the “paper asset’ category.* Conversely, the “hard asset” sectors and sub-sectors like energy producers/transporters, gold miners, copper producers, and agriculture nutrient companies have been the ultimate St. Bernards—i.e., huge dogs. (Real estate is one hard asset that has flourished in the last decade, after its disastrous collapse in 2008 and 2009. However, the high degree of leverage and inflated prices that characterize much of the property market today is worrisome.)

With most US portfolios heavily skewed toward the paper asset category and nearly devoid of hard assets, the stage is set for one of those paradigm shifts that is exceedingly painful for backward-looking, trend-following investors. As noted in last week’s EVA, that is everyone who is heavily involved with today’s most popular investment vehicles--US-focused stock index funds.

Per Jack Ma’s quote at the opening of this EVA, when money is too abundant bad decisions are made and they typically involve the recent performance stars. There’s never been a time in American history when there has been this much excess liquidity greasing the markets for paper assets. If there was ever time to channel your inner contrarian, this is it—asap, if not sooner!

*Certainly, real assets and cash flow underlie most stocks but the above sectors generally performed poorly in the inflationary 1970s while commodity-related issues generated high returns.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.