“The vulnerabilities that have built up around the globe during the long period of unusually low interest rates have not gone away. High debt levels…are still there—and so are frothy valuations.”

-CLAUDIO BORIO, chief economist at the Bank of International Settlements (often known as the central banker for central banks)

Bears repeating. In the financial newsletter industry, John Mauldin is like LeBron James. No one stands taller or is more popular than John with his million-plus circulation of Thoughts from the Frontline. Candidly, John’s work inspired me to start writing the Evergreen Virtual Adviser back in 2006 (so now you know who to blame!).

Coincidentally, he is writing something similar to my “Bubble 3.0” series which he calls “The Debt Train Wreck”. In our July 6th EVA, we included a link to his June 29th installment, titled “Unfunded Promises”. For those of you who missed that issue (God forbid!), here it is again.

Very, VERY, long-time EVA readers will recall the repetitive warnings I gave about the impending housing debacle in 2006 and 2007 in these pages. Frankly, if it wasn’t for John Mauldin, I doubt I would have been nearly as convicted—or convincing—in sounding those alarms. It was through attending his Strategic Investment Conferences in that era of NINJA (no income, no jobs, no assets) lending that I came to believe that it was essential to position client portfolios for the coming crash. It was one of the most important moves of my career and for that alone I will always be grateful to John.

Many alleged experts laughed at John (and yours truly) in those days but that laughter turned to tears a few short years later. In those pre-bubble bursting days, though, it seemed like the insanity would never end. In other words, it was a lot like today.

In the years that have passed, I have been honored to consider John a friend. In fact, I chatted with him on the phone this week and we commiserated over what we both see as another pending debt disaster. It bothers us both greatly that investors are currently totally oblivious to the long-term risk posed by this enormous bubble in debt issuance. If you think that’s an exaggeration, just wait two paragraphs.

In this month’s Guest EVA, we are running the July 13th installment of his must-read series. To his considerable credit, John is refusing to turn a blind eye to the brewing debt crisis we’ve allowed our policymakers to lead us into—again. Many, of course, disagree with that but, as the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan supposedly said (I’m always hesitant to make absolute attributions of pithy sayings these days): “You can have your own opinions but not your own facts.”

As you will soon read, John brings up some findings by the Institute for International Finance (IIF) outlining the staggering rate of debt growth that has occurred over the past decade. To put a huge exclamation point on this, right after John published “The Debt Train Will Crash“, the IIF released what I think is the most horrifying statistic I’ve seen in this regard—and that’s really saying something given the enormity of prior numbers. To wit, late last week, the IIF reported that global debt has exploded by $25 trillion in just ONE YEAR. If that doesn’t send chills up your spine, perhaps you’ve been enjoying too many adult beverages.

For the US government alone, the numbers are appalling. The official debt figure of $21 trillion is awful enough, but the off-balance sheet liabilities of Social Security and Medicare/Medicaid have become, to use a highly technical term, ginormous. These amount to another $50 trillion and, possibly, as high as $200 trillion (by the way, the former number comes from the Congressional Budget Office and the latter from a highly respected source).

Under our current tax structure there simply isn’t enough revenue to finance these benefits. And less affluent US citizens are almost certain to become extremely grumpy if their Social Security check gets cut by a third or their Medicare card doesn’t work. So vast new amounts of tax revenues need to be found. If you are a high net worth American, you’ve got a big bulls-eye on your back.

John believes we will eventually see a Value-Added Tax (VAT), essentially a national sales tax, which has the potential to raise vast sums for the government. Our mutual friend, venerated economist Woody Brock, believes a wealth tax is coming, something I’ve long suspected. Or, it could well be both.

Regardless, a massive tax increase—that would likely dwarf the recent Trump tax cut—is not a bullish development. It may drive some of our biggest taxpayers out of the country, similar to what certain high-tax states are experiencing now.

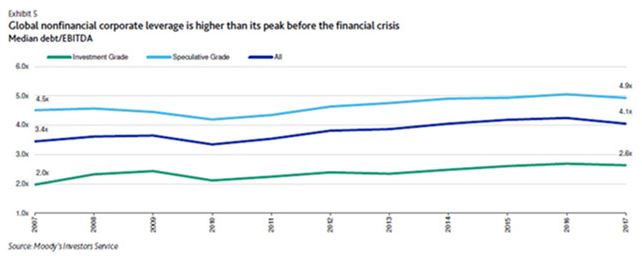

John correctly notes that this is far from just a government debt issue. Global corporations have been dramatically leveraging up. Collectively, they now have a debt-to-cash flow (EBITDA) ratio of 4.1 times versus 3.4 times in 2007. In other words, relative to the cash flow necessary to cover interest costs, the planet’s non-financial companies are 20% worse off than they were at the top of what had been the biggest credit bubble of all-time.

As John also perceptively points out, “lower asset prices won’t be the result of the next recession, they will cause that recession”. My partner Charles Gave has observed that as well, and even Fed chair Jay Powell has opined that the last two recessions were caused by plunging markets rather than vice versa. In my mind, this is critically important and underscores the dangers to the real economy posed by the realities of margin debt at the highest level since WWII and US stocks that remain among the most expensive of the last sixty years—if not nearly ninety.

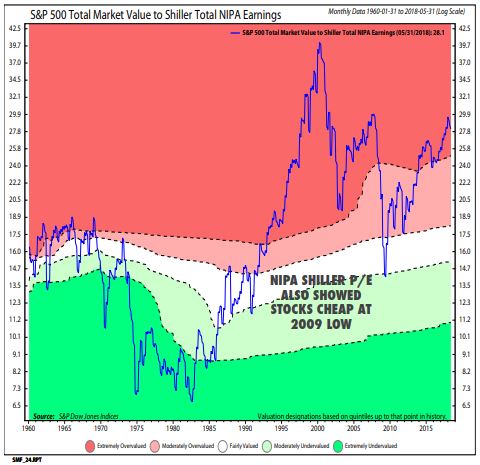

To close on that last note, many experts have criticized the Shiller, or cyclically-adjusted, P/E for being distorted by the profit collapse of the Great Recession. Accordingly, Wharton professor and best-selling author (“Stocks For The Long Run”) Jeremy Siegel has created a variation of the Shiller P/E that uses National Income and Product Account (NIPA) profits. These have been much less volatile than S&P earnings and, thus, show a less alarming reading. The problem, as you can see below, is that even using this approach valuations today are at a rarely attained peak, one which was only briefly exceeded during the nuttiest days of the tech bubble.

Considering the Himalayan mountains of debt out there now and interest rates rising materially, does that make sense to you? Or does it sound like the kind of situation that could trigger the next recession?

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

THE DEBT TRAIN WILL CRASH

By John Mauldin

We are approaching the end of the Debt Train Wreck series. I’ve spent several weeks explaining why I think excessive debt is dragging the world economy toward an epic crash. The tracks ahead are clear for now but will not remain so. The end probably won’t be pretty. But there’s good news, too: we have time to get our portfolios, our businesses, and our families prepared.

Today, we’ll look at some new numbers on just how big the problem is, then I’ll recap the various angles we’ve discussed. This problem is so big that we easily overlook key points. I hope that listing them all in one place will help you grasp their enormity. Next week, and possibly a few after that, I’ll describe some possible strategies to protect your assets and family.

Off the Tracks

Talking about global debt requires that we consider almost incomprehensibly large numbers. Our minds can’t process their enormity. How much is a trillion dollars, really? But understanding this peril forces us to try.

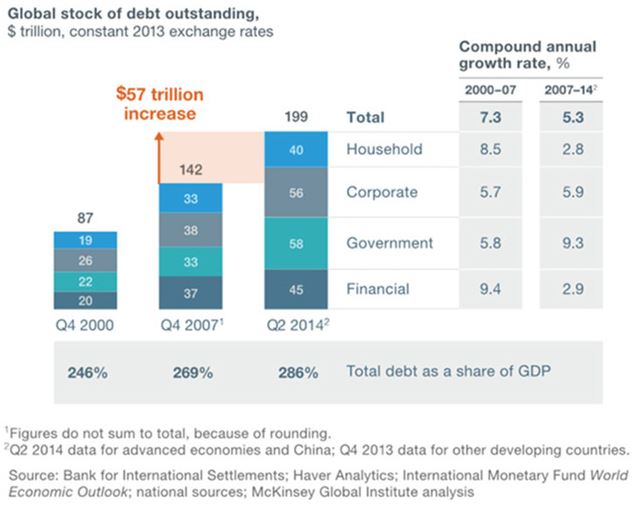

Earlier in this series, I shared a 2015 McKinsey chart that summed up global debt totals. They pegged it at $199 trillion as of Q2 2014. Note that the debt grew faster than global GDP. Everything I see suggests it will go higher at an ever-increasing rate.

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

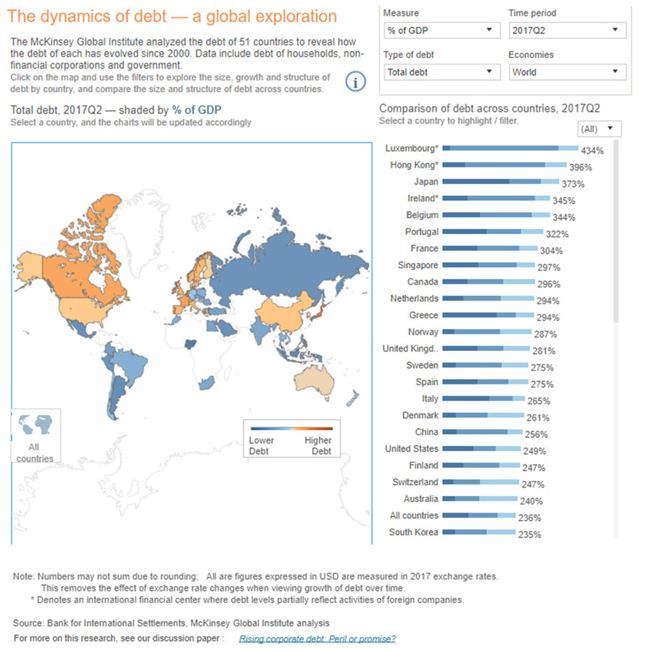

Last month, McKinsey published a very useful online tool for visualizing global debt, based on Q2 2017 data. It shows a total of $169T, which is less than McKinsey said in 2014. Is debt shrinking? No. The new tool excludes the Financial debt category, which was $45T three years earlier. A separate Institute for International Finance report said financial debt was $59T at the end of 2017. These aren’t quite comparable numbers, but in the (very big) ballpark range we can estimate total debt was somewhere between $225T (per McKinsey) and $238T (per IIF) in mid-2017. (IIF’s latest update last week says it is now $247T). [Editor’s note: this piece was originally published on July 13th; as of this Guest EVA publication date, the IIF update had occurred the week before last.]

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

That would mean world debt grew something like 13% in the three years ended 2017. If so, it would be a slowdown comparable to the 2007-2014 pace McKinsey showed in the chart above—but still faster than world GDP grew in those three years. McKinsey says global debt (ex-financial) grew from $97T in 2007 to $169T in mid-2017.

Importantly, households aren’t driving this. Governments accounted for 43% of the increase McKinsey cites and nonfinancial corporate debt was 41%. That is where I think the coming train crash will originate. Governments have more debt than corporations, but also more tools (like taxing authority) to manage it.

On the other hand, governments also have massive “unfunded liabilities” that don’t show in the numbers above. So, they aren’t in a great position, either.

Bottom line: There’s going to be a train wreck here. Which train will go off which track is unclear, but something will. And we’re all going to feel it.

Woes to Come

We launched this journey in my May 11 Credit-Driven Train Crash letter. I described my friend Peter Boockvar’s perceptive statement: “We no longer have business cycles, we have credit cycles.”

His point is subtle yet critical. Post-crisis growth, mild as it’s been, has been largely a function of debt, which central banks encouraged and enabled. The result was inflated asset prices without the kind of “recovery” seen in previous business cycles. Interest rates, i.e. the cost of debt, thus became critical.

With rates now moving up again, premium asset prices are losing their raison d’etre and will stabilize and eventually fall. Peter Boockvar says this, not the conventional business cycle, is what will set off recession. That’s key. Lower asset prices won’t be the result of the next recession; they will cause that recession.

I showed in that letter how companies will need to refinance about $4T of bonds in the next year, almost all of it at higher rates. This will hit debt-burdened companies that are already struggling and make it almost impossible for some to keep operating. Lenders, i.e. high-yield bond holders, will try to exit their positions all at once only to find a severe shortage of willing buyers.

The following week in Train Crash Preview, I listed the steps in which I think the crisis will unfold. They fall in four stages.

Next in High Yield Train Wreck, we dove deeper into the dream-driven high-yield bond market exemplified by this year’s nutty $702-million WeWork issue. I quoted Grant Williams, who wrote a masterful takedown of this craziness.

Ten years into the ongoing laboratory experiment being conducted by the world’s central banks, everywhere you look there are multiple examples of the kind of lunacy those policies have fomented by reducing the cost of capital to virtually zero and forcing investors to take risks they would ordinarily avoid in order to find some kind of return.

WeWork is one example of a company for whom, in the face of rapid growth, massive negative cashflows aren’t a problem, but there are plenty of others. Uber, AirBnB, SnapChat and, of course, Tesla have all captured the imagination of investors thanks to lofty dreams, articulated by charismatic CEOs—but the day things turn around and the economy begins to weaken or, God forbid, investors seek a return on their investment as opposed to settling for rolling promises of gigantic, game-changing revenues to come, it is over.

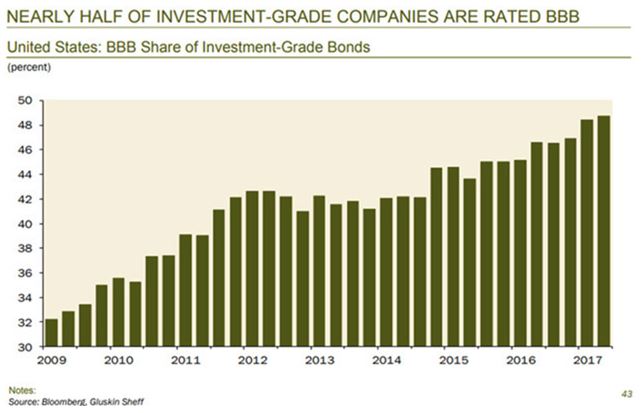

We went on to talk about the insanity of yield-hungry investors practically throwing cash at borrowers while demanding little in return. I also showed how this is not simply a junk-rated company problem, since almost half of investment-grade companies are rated BBB and could easily slip to junk status in a downturn.

Source: On My Radar

Source: On My Radar

Growing Leverage

The week after we turned to Europe in The Italian Trigger. Unfortunately, Italy isn’t Europe’s only problem. The big Kahuna is Germany, which spent years offering generous vendor financing to the rest of the continent to entice the purchase of German goods. The result: a giant trade surplus for Germany and giant, unpayable debts for those who bought German goods.

The Euro currency union is fatally flawed because it leaves each member state to set its own fiscal policy. There are good reasons for that, but it is not sustainable indefinitely. The Eurozone must get either much more centralized or fall apart. All the Rube Goldberg contraptions the ECB and others invent are temporary fixes. They’ve worked so far. They won’t work forever.

I still think the most probable scenario is that Germany and the Netherlands (and the rest of the northern European cabal) reluctantly agree to let the European Central Bank mutualize all the sovereign debt, taking onto their balance sheet and issuing new ECB-backed debt for the entire zone. There would have to be serious constraints on running deficits after that point, but it would prevent a breakup, or at least delay it for another decade or so.

Of course, within a few years those new deficit constraints would be ignored. I said in a previous letter Germany will need to collect almost 80% of GDP in 30 years in order to be able to deliver its promised healthcare and pensions. Their inability to do that will be evident much sooner. Germany will end up becoming one of the biggest problems.

The next installment, Debt Clock Ticking, was a bit philosophical. I talked about debt letting you bring the future into the present, buying things you couldn’t afford if you had to pay for them now. But the entire world went into debt for the equivalent of tropical vacations and, having now enjoyed them, realizes it must pay the bill. The resources to do so do not yet exist. So, in the time-honored tradition of lenders everywhere, we extend and pretend. But with our ability to pretend almost gone, we’re heading to the Great Reset.

Source: Moody's Investors Service

Source: Moody's Investors Service

Then I reviewed some of the McKinsey and IIF numbers and described the amount of leverage that’s built up in the system. Just a decade after the Great Recession, the average non-financial business went from 3.4x leverage to 4.1x. They are now roughly 20% more leveraged than they were the last time all hell broke loose. CEOs and boards seem to have learned little from the experience—or maybe learned too much. If you believe the Fed has your back, then leveraging to the moon makes sense.

Pension Problems

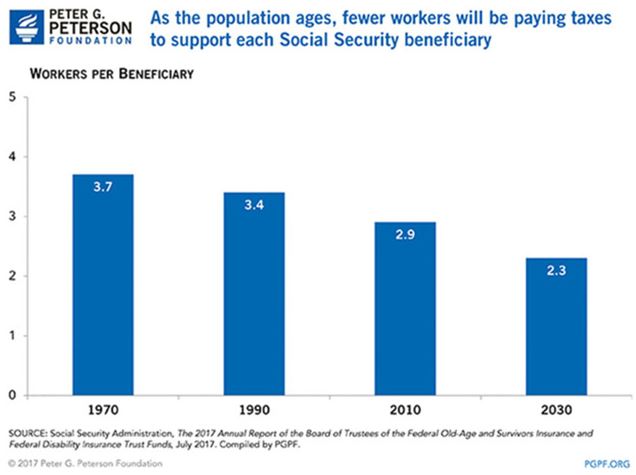

The last three letters in the series got personal for many readers as I talked about pension debt. In The Pension Train Has No Seat Belts, we looked at the demographic challenge facing US pension funds, mainly state and local government plans but also some private ones. We are asking a shrinking group of working-age people to support a growing number of retirees and that’s just not going to work.

Source: Peter G. Peterson Foundation

Source: Peter G. Peterson Foundation

The promises employers made to workers are a kind of debt. They’re the borrowers, workers are the lenders… and unlike in 2008, this time it will be lenders who get hurt the most. A new report by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) shows the unfunded liabilities of state and local pension plans jumped $433 billion in the last year to more than $6 trillion. That is nearly $50,000 for every household in America.

Nor is this only a US problem, as we saw in Europe Has Train Wrecks, Too. According to the World Economic Forum, the United Kingdom alone has a $4-trillion retirement savings shortfall that will rise to $33 trillion by 2050. This in a country whose entire GDP is only about $2.6 trillion and doesn’t account for the increasingly likely disaster Brexit will be. Switzerland, Spain, and others have similarly dire outlooks, often driven by even worse demographics than we have in the US. Germany, as noted above, is simply off the rails.

Finally, in Unfunded Promises, we reached the ultimate debt problem: US government unfunded liabilities. On paper, Washington’s debt is about $21.2 trillion… but that doesn’t include the $13.2-trillion unfunded, off-the-books Social Security liability, or the $37-trillion Medicare unfunded liability. Those aren’t my numbers, by the way; they come from the Social Security and Medicare trustees and are probably understated. My friend, Boston University professor Larry Kotlikoff, thinks it should be more like $210 trillion. He has a considerable amount of published works and a book he co-authored with fellow Texan Scott Burns.

That’s not all. The federal government also has liabilities for civil service and military pensions, veteran benefits, some defaulted private pensions via PBGC, and open-ended guarantees to entities like FDIC, Fannie Mae, and more.

The budget outlook is horrible even without all that, too. The Congressional Budget Office thinks federal debt will be 200% of GDP by 2048, and that by 2041 it will take all federal tax revenue just to support Social Security, the various health care programs and pay interest. That’s before defense or anything else the government does. And that’s assuming relatively high growth and NO recessions and a rising stock market forever as we ride off into the sunset.

I wrapped up quoting my friend Dr. Woody Brock, who thinks the most likely outcome will be wealth taxes at federal, state, and local levels. I truly hope he’s wrong about that, but I fear he is not. My preferred new tax for the US would be a VAT that eliminates the Social Security tax (thus giving lower-income workers and businesses a raise) but still funds Social Security and healthcare. Other government expenditures would be funded from income taxes which could be reduced significantly, and even eliminated on incomes below $50,000. Now that’s a tax cut that would boost the economy and balance the budget.

There really are only two ways to solve this problem: massive taxes on someone, or a debt liquidation of some kind. And remember, if you are getting a retirement pension fund and/or healthcare, your benefits are part of that “debt liquidation.” Both will be painful. We have pulled forward our spending and must eventually pay for it. The time is coming. Please don’t shoot the messenger.

Let’s summarize. Global debt is over $225 trillion. By the beginning of the next decade it could be over $300 trillion. Global government unfunded liabilities are easily in the $100-trillion range today and could easily double by the end of the next decade. Debt service, pensions, and healthcare will take 20-25% of GDP in many countries (more in some of Europe).

Your mileage may and will vary by country. In some, there will be inflation and in others, deflation. We will be thinking the unthinkable and choosing policies that seem insane to even mention today. But then, think about what Japan is doing. And the ECB. Add in automation and the loss of hundreds of millions of jobs in the OECD countries. Then think about what will happen in the emerging economies.

But at the same time, imagine all the new companies being built and fortunes made. The opportunities. The situation, as Doug Casey once quipped, “Is hopeless, but not serious.” Not yet. Not for you and me.

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

* Credit spreads are the difference between non-government bond interest rates and treasury yields.

** Due to recent weakness, certain BB issues look attractive.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.