“The time to IPO for most startups has substantially elongated, in many cases ten or more years from founding.”

–SCOTT KUPOR, Venture Capitalist and author of Secrets of Sand Hill Road

Ben Horowitz, famed entrepreneur and venture capitalist, once quipped that as a startup CEO he “slept like a baby [because he] woke up every two hours and cried.” As many others at the head of early-stage businesses can attest, Ben isn’t overreaching all that far in his comparison. While many factors play into the often-disrupted sleep patterns of entrepreneurs, perhaps the most jarring is the fact that the vast majority of early-stage companies are destined to flop. Statistically speaking, nine out of ten startups will fail.

However, for the relatively few businesses that go on to achieve long-term success, a mysterious reality faces them: the median time to IPO* for a company has ballooned from four years to ten years over the last two decades. And, while we will dive deeper into the possible reasons for this below, it’s important to understand the impact this has had on public markets.

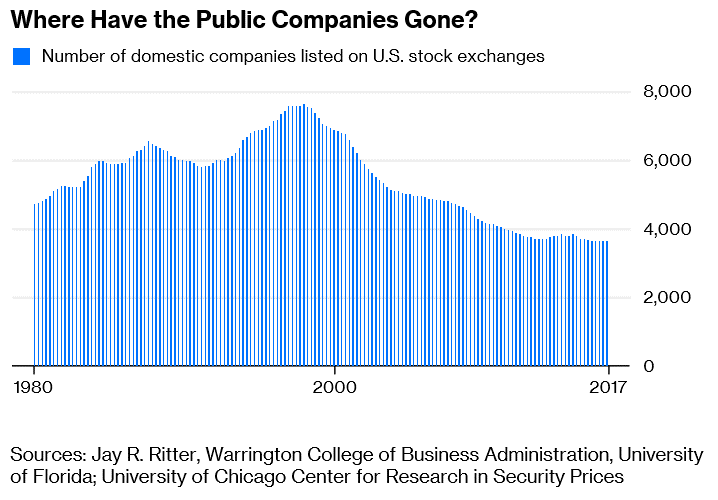

Consider, for a minute, that there were roughly 7,500 publicly traded companies and 300 IPOs per year on U.S. exchanges before the turn of the millennial – which coincided with the height of the dotcom bubble. Today, the number is closer to 3,600 total publicly traded companies and a little more than 100 IPOs per year, or down more than half over the last two decades.

So, what’s happening? Simply put, over the past 20 years, there has been a much higher clip of public companies going private, merging with or acquiring other companies, or ceasing operations completely than the number of new companies entering public markets. And, although the swell of IPOs this year has sparked some enthusiasm around the idea that those numbers might begin to tick higher, the wave has incited an equal amount of skepticism as many of these companies (some of which we wrote about in our Chasing Unicorns: IPOs to Watch newsletter) have operated for a decade or longer without turning a meaningful or consistent profit. One thing to note in regard to the “disappearing publicly-traded stock” theme is that the steepest declines occurred from 2000 to 2011, further highlighting the mania in the ‘90s dotcom era that brought a significant number of marginal entities to public markets that either failed or were acquired.

But, before going any further, let’s take a step back.

If we assume that the current trend holds and the number of publicly traded companies continues to decline, one alarming repercussion is that the average investor will have fewer and fewer opportunities to invest in a diverse array of securities, specifically small-to-medium cap businesses. Last year, Nasdaq’s CEO, Adena Friedman, warned that if the trend continues, “job creation and economic growth could suffer, and income inequality could worsen as average investors become increasingly shut out of the most attractive offerings.”

Related to the factoid mentioned at the beginning of this article, the case of the elongated IPO further compounds this issue by bringing companies to market later in their funding cycle, thus introducing them to public markets at loftier valuations that, in the long-term, will likely not be sustained by business models that fail to create consistent profits. The New York Times ran a telling article on this point in March titled, “In This Tech I.P.O. Wave, Big Investors Grab More of the Gains: Unicorn Companies Are Finally Going Public, After Large Gains Have Been Captured by Elite Early Investors.”

While the trend of the elongated IPO is clear, there is still plenty of mystery surrounding how we got here. Below are four of the most popular theories as to why the median time to IPO has more than doubled over the last two decades, while the number of public companies has declined by 50%:

Traditionally, an Initial Public Offering has been the mountaintop to which every company strives to ascend. However, with increased costs related to regulatory and compliance requirements of being public, diminished appetite for small-cap stocks by the largest mutual funds, more funding options for private companies, and the increasing proclivity of large-cap companies to acquire small-cap companies at lofty prices, it is apparent why many businesses are content to stay private for longer these days.

The unfortunate side-effect of this trend is that the average investor will likely miss out on one of the most attractive periods to invest in a young, promising company. The good news is that there are a plethora of attractive U.S. and international securities trading in public markets that we believe can provide investors with outsized returns over time. Another piece of good news is that, at Evergreen Gavekal, we have opened our doors for qualified investors to invest in some highly attractive private companies as well. Investors just need to know where to look, when to look and which investment professional to pick as their guide.**

*IPO stands for Initial Public Offering and the process by which private companies make their stock available to trade in public markets.

**For more information on how Evergreen Gavekal can help you develop a balanced investment portfolio, please reach out to info@evergreengavekal.com.

Michael Johnston

Tech Contributor

To contact Michael, email:

mjohnston@evergreengavekal.com

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.